Small Details You Missed In Things Heard & Seen

This content was paid for by Netflix and created by Looper.

For many families, moving away from the big city for a quiet life in the suburbs may be a dream come true, but for Catherine Clare (Oscar-nominated Mank star Amanda Seyfried) in Things Heard and Seen, country life becomes nothing short of a nightmare.

The film, which adapts Elizabeth Brundage's novel All Things Cease to Appear, follows restoration artist Catherine and her husband George (James Norton) as they move to upstate New York after he takes a new job as a college professor. Soon, their family devolves from an ambitious — albeit, troubled — young couple with a kid into a truly haunted trio who must deal with dark and dangerous secrets about their new home and themselves. As Catherine tries to uncover the truth about the paranormal presence in her house, she slowly discovers that the life she has made with George is built upon a foundation of lies, and things take a deadly turn for the worse.

In addition to painting a grim portrait of a family in crisis, Things Heard and Seen also contains subtler points that take a very keen eye to catch. Here's a look at some of the smaller details you might not have initially noticed in the film.

An ominous opening

Before we even meet Catherine and George, we get an ominous warning about the story to come. The film opens on an old quote from the Swedish theologist Emanuel Swedenborg, which reads: "This I can declare... things that are in heaven are more real than things that are in the world." Alone, that passage might not immediately give audiences gooseflesh, but once the film spells out the relevance of those words, it's a hair-raising sentence indeed.

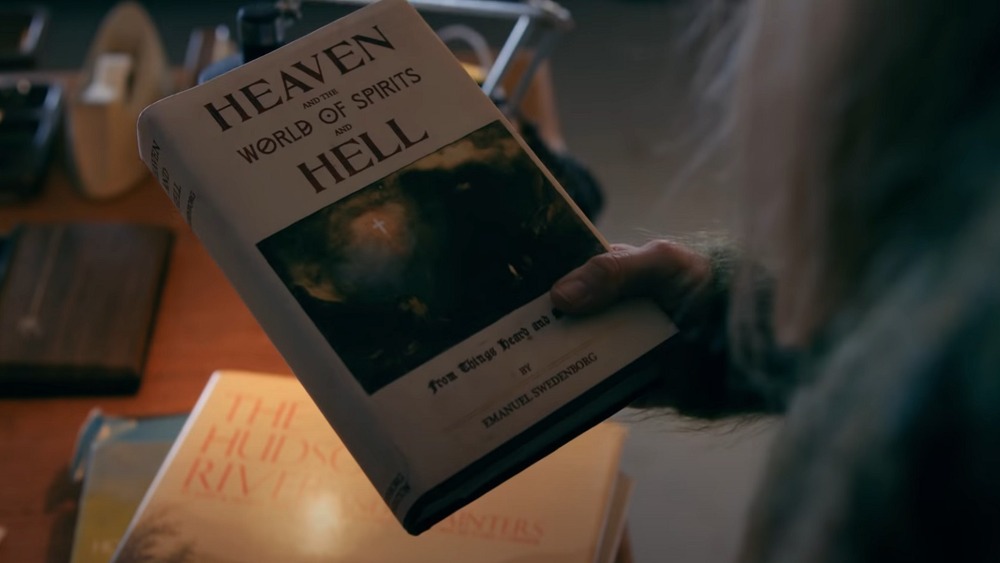

Throughout the film, Swedenborg's legacy becomes a crucial part of Things Heard and Seen, primarily because George's new boss, Floyd DeBeers (F. Murray Abraham) is quite a fan of Swedenborg's work. In fact, the reason that Floyd hired George in the first place is that Floyd liked the section of George's dissertation discussing Swedenborg's influence on landscape artist George Inness. Inness was such a believer in Swedenborg's teachings that one of Inness' pieces, "Valley of the Shadow of Death," was directly inspired by the philosopher. In turn, the painting is used on the cover of a modern printing of Swedenborg's book Heaven and its Wonders and Hell From Things Heard and Seen. That book makes the rounds in the movie, but the citation of Swedenborg's passage is more than just a wink to the text's prominent presence in the film.

What Swedenborg is saying in this quote proves to be true in Things Heard and Seen. As Floyd and George discuss, Swedenborg believed that every living being has a spiritual counterpart that is as real and impactful as its physical presence. Indeed, as we later learn from the ghost that occupies the Clares' home, some very real people return to the world in spiritual form — for better and for worse.

A spiritual homage

The cover of Swedenborg's book also proves to be quite prescient about how the Clares' story will end. First, the painting comes back to literally haunt George after he murders Floyd for threatening to expose George's false credentials during a slideshow that only features Innes' artwork, which the two often discussed. On top of that, "Valley of the Shadow of Death" also serves as a visual preview of George's final moments.

After it becomes clear that George will likely face conviction for Catherine's death thanks to the unexpected survival of George's second victim, Justine Sokolov (Rhea Seehorn), George decides to set sail. It's unclear if George hopes to cover up his crimes by murdering Justine or if he's simply trying to escape to start a new life, but neither aim is accomplished. George becomes trapped in a terrible storm that appears to take him out. Just as the movie opens with a lush painting of the landscape in which the movie begins, the last scene slowly morphs into a stormy still frame that looks a lot like Inness' piece. In the movie's final shot, the sea swells as a brilliantly bright cross breaks through the stormy clouds — only, for George, the cross is upside down.

A chilling callback

Inness' painting isn't the only piece of art that helps shape the scenery of George's final moments. During a class trip to New York City's National Gallery of Art, one of George's students asks about the Thomas Cole painting, "Voyage of Life: Manhood." George explains that the painting depicts the artist's belief that the sailor has lost "the confidence of youth," adding, "Go check out the sailor's hands. They're no longer on the tiller." Art experts point out that this may mean that the sailor has abandoned any effort to steer his own vessel and is now relying on faith to carry him through the storm.

George, however, continues trying to exert control over his tiller until the very end of his voyage. As his sailboat struggles in the swarming storm, George loses control of the steering device several times but keeps reaching back for it. Unfortunately, that effort proves to be quite fruitless. The waves eventually turn into fire and consume the boat with George aboard. The moment then freezes into a painting that resembles the works of Cole and Inness — only, instead of capturing the subject's ascent as he joins the angels, it looks like George's fate is bleaker. George, who was an admitted fan of Cole's work, appears to have made his own alternative version of the same storyline — one in which the sailor maintains his hubris until the very end, with dark consequences to follow.

A prescient pairing

Another bit of clever visual imaging that comes into play during the film's final moments happens when Justine wakes up from her coma, which was caused by George running her off the road and forcing her car to crash. As Justine returns to consciousness, she has a vision of Catherine and the ghost of another woman who fell victim to violence in Catherine's house. The way the two spirits stand together directly calls back to the curious inscription on the ring that Catherine found in her kitchen.

The ring belonged to the mother of orphaned boys Eddy (Alex Neustaedter) and Cole (Jack Gore), and Catherine's discovery of the bauble both results in one of her earliest encounters with the specter that haunts her home and inspires her to research exactly what happened to the people who lived there before. During this investigation, Catherine learns the grim fate of the boys' mom and realizes that history has a strong chance of repeating within her own family.

A friendly ghost

While Catherine certainly has reasons to be afraid of the spirit haunting her home, especially given how much it frightens her daughter Franny (Ana Sophia Heger), one of Catherine's earliest encounters with the ghost may actually hint that the presence is on her side.

When we first meet Catherine, it becomes very clear that she has an eating disorder. And throughout the story, George uses Catherine's eating disorder to manipulate her, as well as an excuse to dismiss all of her very-real concerns. Additionally, in the end, George poisons one of the protein shakes that Catherine has been prescribed to drink by her doctor in order to treat her illness. So, when the ghost suddenly starts up Catherine's electric toothbrush and makes it fall from the counter, smashing her glass scale to pieces, it seems like more of a warning than an attempt to scare the young mother.

A telling story

Speaking of early warning signs, there's also a bit of foreshadowing in the scene in which George first introduces himself to his eventual lover, Willis (Stranger Things' Natalia Dyer). George meets Willis while taking Franny to the local library and notices that Willis is reading a book about the Italian painter Caravaggio. In addition to being known for his stunning portraits and grisly scene paintings, Caravaggio was also famous for committing murder. George uses that story to break the ice with Willis.

According to historians, Caravaggio was known for his violent outbursts and, during a fight over either a tennis match or a lover, fatally wounded a man named Ranuccio Tomassoni. Caravaggio then spent the rest of his life on the run, although his aggressions continued in exile. However, fate eventually caught up with the artist, and he died at just 38. The fact that George gleefully references this nugget of history as a means of flirting with a woman certainly speaks to his character — and offers a hint about what he's capable of himself.

An early warning

Things Heard and Seen's relationship with art history is certainly explored throughout the film, but after you see the film's ending its opening scene becomes even more meaningful. In the beginning of the movie, audiences are treated to a slideshow of several art pieces, many of which are from the Hudson River School art movement. Not only do these pictures establish the location of the film and wink at the type of art that George studies, but the slideshow also features some pieces that preview the events and mood of the movie.

Most obviously, the showcase includes Thomas Cole's "Voyage of Life: Manhood," which proves to be a specific and enduring component of the film. Other art pieces contained in the slideshow are equally as prescient. Frederic Edwin Church's "Aurora Borealis" also bears a resemblance to George's last ride, while George Inness's "Approaching Storm" features an idyllic outdoor landscape that is growing ominous due to an incoming weather system. Two other paintings by Cole, "The Oxbow" and "Kaaterskill Falls," have a similarly gloomy tone, with a dark sky that threatens to upend the pastoral bliss of the Hudson Valley.