Things You Forgot Happened In Fight Club

Before we go further, if you have not seen "Fight Club," immediately stop reading this article and come back after we can't spoil it for you.

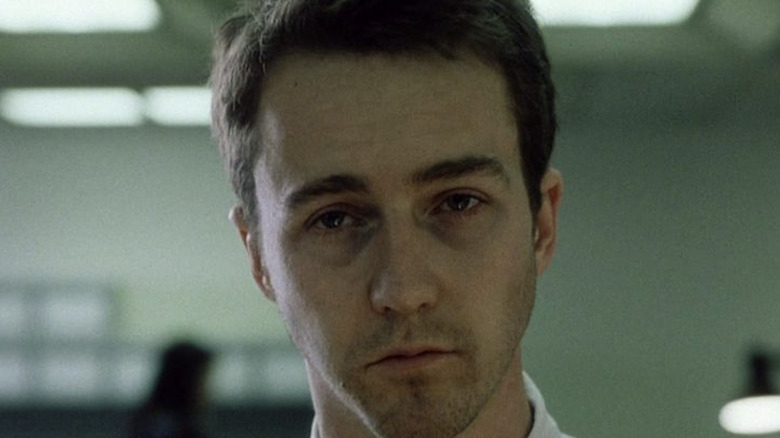

The 1999 darkest of dark comedies, directed by David Fincher and based on a novel by Chuck Palahniuk, brims with anti-establishmentarian pseudo-philosophy and edgelord one-liners, thereby ensuring it a replenishing fandom of college bros and MRA halfwits who don't get the joke. It's also a crackling sensory experience with a bonkers third-act twist; plus career-highlight performances from Edward Norton, Helena Bonham Carter, and Brad Pitt. Sure, some of the biggest "Fight Club" fans are jerks; but we can say the same thing about "Nomadland."

While a box office bummer, the film's audience snowballed on the secondary market. Norton suspects the folks charged with its marketing strategy felt personally attacked by the film; regardless, they did come up with some interesting ideas.

Even with the aid of advertising professionals who were not hostile to its existence, "Fight Club" would've been a tough sell to the mainstream. It's violent, but it's not an action or horror movie. It's not sincere enough to be a drama. It's funny, but not really "ha, ha," funny. While television might be a different story, the film industry has apparently decided "Fight Club" is too weird to imitate. Everyone remembers "Fight Club," which means you can't steal from "Fight Club" without everyone noticing.

But just because "Fight Club" kisses your brain, then drowns it in lye to leave a chemical burn scar, that doesn't mean we won't forget a thing or two.

We see Tyler multiple times before he introduces himself

The film's nameless Narrator — played with deadpan perfection by Edward Norton — meets Brad Pitt's hyper-charismatic anarchist Tyler Durden when they coincidentally purchase tickets next to each other on an airplane ... or so The Narrator thinks.

But well before Tyler introduces himself as a humble soap salesman with a, perhaps, ill-advised tendency to reveal his vast knowledge of homemade explosive recipes to total strangers, he's actually all over the place. Tyler is one of the waiters in a welcome video at a hotel The Narrator stays at on a business trip; Tyler appears for a split second — as if he's crossing over from The Narrator's subconscious to conscious mind — on four separate occasions before he calls attention to the sick desperation in The Narrator's laugh; and of course, we see Tyler clear as day traveling in the opposite direction across from The Narrator on an airport escalator.

"If you wake up at a different time, in a different place, could you wake up as a different person?" The Narrator asks himself, or more precisely, he asks the audience. He might as well be telling us, "I am Jack's foreshadowing."

Most of Marla's behavior makes no sense until your second watch

Marla Singer — played by Helena Bonham Carter in a performance nominated for most convincing American accent in U.K. thespian history — is occasionally dismissed as a manic pixie dream girl trope (MPDG) by critics who aren't paying attention. Admittedly, she checks a few MPDG boxes — Marla's the only major female character in an otherwise male-dominated story; the protagonist is a bored, seemingly normal depressed guy; and Marla's conventionally attractive and eccentric. But Marla doesn't rescue a male character from a bland, sunshineless existence. Instead, her clearly troubled but nevertheless interesting life is ruined by her delusional cult leader boyfriend. "You are the worst thing that ever happened to me," Marla tells The Narrator, in one of her final lines of dialogue. Nobody saves anybody from anything in this movie.

Does Marla Singer subvert the manic pixie dream girl troupe in a movie released six years before the term "manic pixie dream girl" entered the critical lexicon? We report, you decide.

But the fact remains that most of her interactions with The Narrator make zero sense until your second watch. The first time you see "Fight Club," Marla's sexual overtures and familiarity towards The Narrator make her appear impulsive, nymphomaniacal, and maybe a little trashy. Once you know the whole context of the story, Marla looks like the only main character who behaves more-or-less like a normal person.

Jared Leto gets destroyed

There aren't a ton of famous actors in "Fight Club" — at least, not by 1999's standards. The general public of the late '90s certainly recognized Meat Loaf in his role as testicular cancer survivor and founding Project Mayhem foot soldier Robert "Bob" Paulson; but aside from Meat Loaf, the three leads are the only real "names" ... as long as you don't count retroactive celebrity status.

Before a starring turn in Darren Aronofsky's "Requiem For A Dream" and a memorable supporting role in "American Psycho" turned Jared Leto into an actor Hollywood took seriously in 2000, he was principally recognized as Jordan Catalano on the crucial '90s melodrama "My So-Called Life." As the generally detached and stoic Jordan, Leto never got a chance to do much of the heavy lifting on the single-season series that also introduced America to a teenage Clare Danes.

But in "Fight Club," although he doesn't get much screen time, the character known only as "Angel Face" marks a major departure for Leto's career. The cheerful, enthusiastic Angel Face doesn't share Jordan's sulky, Seattle slacker stereotype sensibility; and Jordan certainly wouldn't take that many punches and still come back for more of Project Mayhem's shenanigans.

Fight Club is loaded with product placement

Are you aware that Generation X is known for an ironic, detached sense of humor? Have you ever noticed the satirical disposition in Gen Xer art often seems to lampshade an unresolved collective tension between their discomfort with mass consumerism as a concept, and their shrugging acceptance of mass consumerism as an actuality? Take Kurt Cobain wearing a "Corporate Magazines Still Suck" t-shirt on the cover of Rolling Stone for a case in point.

The imaginary Gen Xers in "Fight Club" obviously opt to smash consumer culture and neo-liberal capitalist homogeny. But since Gen Xers in the real world had collectively bought into the system completely by 1999, unlike its characters, the film itself exists in complete devoted compliance to the many fine brands that to this very day sustain life, joy, and safety as we know it — Xerox, Gucci, Apple, Budweiser, and a whole bunch of others.

According to legend, a Starbucks cup finds a way into the background of virtually every Fight Club scene. We have not confirmed the veracity of that statement. But even if it isn't quite true, you don't have to pay especially close attention to notice folks in Fight Club drink a monumental amount of Starbucks.

Fight Club is loaded with homoeroticism

Author Chuck Palahniuk came out of the closet in 2004, likely forcing more than a few of his fans to disregard old assumptions about the connection between sexuality and traditional notions of masculinity. It also invited reexaminations of his work; while Palahniuk had little direct participation in the film adaptation of "Fight Club," we can speculate David Fincher caught on to the novel's erotic subtext in ways many of us didn't until 2004.

In the film's opening scene, Tyler Durden holds a gun at waist level, pointed down, with the barrel directly in The Narrator's mouth — and that description's as graphic as this website allows us to get. Much of the movie's action revolves around half-naked men getting sweaty and energized within close personal proximity of each other. And there's hardly any women in the film apart, of course, from Marla Singer and Chloe the cancer patient who only wants to have sex one final time before she dies. Does The Narrator take her up on that offer? He does not. The Narrator also shoots down multiple advances from Marla. The Narrator spends the whole movie rejecting sex with women (unless, of course, you count Tyler's sexual escapades with Marla, because The Narrator is Tyler) so he has more time to hang out next to shirtless men with washboard abs.

Putting "Fight Club" in the category of LGBTQ cinema might be a stretch. But one thing it absolutely is not is a heterosexual film.

Tyler smokes way less during the final 1/3rd of the movie

Observant viewers may notice that when Tyler Durden offers The Narrator a cigarette shortly after their first meeting, The Narrator declines. But not long thereafter, The Narrator huffs down nicotine-flavored carcinogenic fumes like it's going out of style — which as it turned out, it was.

Meanwhile, Tyler's cigarette consumption moves in the inverse trajectory. During roughly the first two-thirds or three-quarters of the film, he's smoking constantly. By the end, he demonstrates some pretty intense cardiovascular endurance while pummeling The Narrator to a senseless pulp. In fact, he barely gets winded. His lungs seem to work in perfect tip-top shape.

In a scene that would've been universally lauded by public health experts had it not been removed from the final cut, Tyler tells The Narrator that he has quit smoking. The decision doesn't stick. Regardless of where the announcement would've hypothetically appeared, Tyler clearly smokes a cigarette during the big reveal of his true identity, which would've contradicted his previous statement of a newfound tobacco-free lifestyle.

But since that's when we find out Tyler's intangible, is it possible imaginary people don't have to worry about damaged lungs the way the rest of us do?

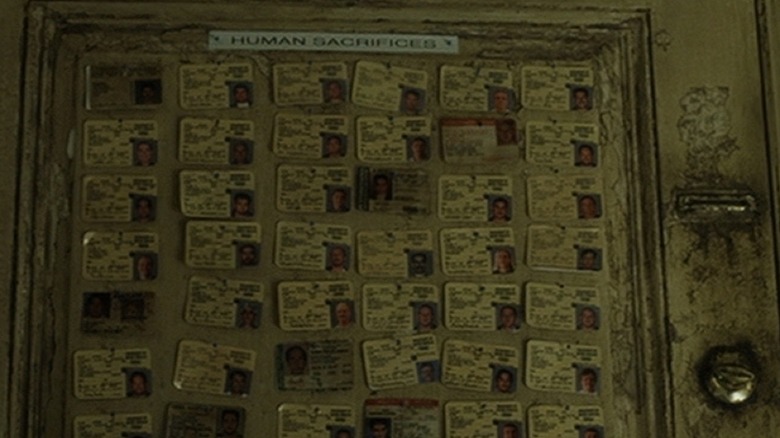

Tyler's got driver's licenses hanging all over his bedroom door

Whether Tyler Durden is a hero, a villain, or neither, remains a debated topic.

There's a threshold of straight-up evil the movie version of Tyler never crosses. For instance, he makes sure buildings are 100 percent unoccupied before he blows them up — a precaution that the novel's version of Tyler, incidentally, does not bother taking.

In what's probably the best example of Tyler as a malicious force for the perceived greater good, he threatens to execute Raymond J. Hassel (Joon Kim) — a convenience store clerk — unless Raymond quits his pointless minimum wage job and goes back to veterinary school. This is, in Tyler's words, a "human sacrifice."

Essentially, Tyler's reminding a random stranger that he can be killed at any time, so he shouldn't waste his life. It's a nice thing that Tyler does! A terrifying, very illegal, and highly ill-advised nice thing!

Raymond is the only human sacrifice the audience ever sees. However, when The Narrator scrambles around in a futile attempt to prevent Tyler's controlled mass-demolition, we see Tyler's bedroom door is completely covered with driver's licenses used to keep track of additional human sacrifices.

That right there is a lot of folks Tyler Durden is directly responsible for sending back to college — because thanks to him, they'll die if they don't. So, um .... hurray?

The bus Marla gets on is obviously full of space monkeys

Here's a detail maybe you didn't "forget" so much as didn't notice. After The Narrator explains to Marla that he likes her a lot and she's in very serious danger, he pressures her into leaving town for a while, puts her on a bus, and makes certain that he isn't able to see where the bus is headed. If he knows where Marla's going, then Tyler knows, and the effort to protect Marla from Tyler or Tyler's henchmen is for naught.

But if you watch the scene closely, you'll notice the other passengers on the bus descend upon Marla almost immediately upon her boarding.

If we presume these passengers are members of Project Mayhem — which we should, because they are — then it seems Tyler predicted The Narrator's actions and made sure he controlled the only bus that would be available for Marla to board. Or maybe by this point, Tyler controls all the buses? Or perhaps, Tyler doesn't wield any direct power over any individual bus, but Project Mayhem has grown so ubiquitous than its members would've kidnapped Marla no matter where The Narrator tried to send her to lay low?

None of these questions matter, but they're fun to toss around.

Many reasons why this movie had to come out in 1999

The ongoing discourse surrounding "political correctness" or "wokeness" or whichever euphemism conservative pundits are using this week is generally the most tedious thing ever; but it becomes a little more interesting when applied to "Fight Club" — a male power fantasy (in which all the main characters are white) that is also a scathing critique of male power fantasies.

While it has aged better than a few other movies from the '90s, its timing was very fortuitous, as the 9/11 attacks made funny movies about sexy, cool terrorists impossible to produce just a couple years later.

While certain lines have had their misogynistic implications inflated — in particular, an observation Tyler makes about existing within a "generation raised by women" gets routinely quoted without context — "Fight Club" probably doesn't count as a feminist film. With only one female character who appears in more than one scene, "Fight Club" fails the Bechdel test by many miles.

Instead, the film's worst edgelord stuff is its handling of Bob Paulson — founding Project Mayhem space monkey and seemingly decent guy. A hormonal imbalance has left Bob with large womanly breasts, and the film plays his condition up for laughs.

Is it transphobic? Maybe. But it is definitely mocking a cancer symptom, which was in pretty questionable taste even back in 1999.

The frame of a penis in the ending

When The Narrator tells the audience about Tyler Durden early in the movie, he notes Tyler works as a projectionist at a movie theater — among other side-gigs — to supplement his homemade soap-selling business. In addition to the extra income, the job grants Tyler opportunities to splice single frames of sexually explicit adult content into PG- and G-rated films. When these subtly defaced films screen, for a millisecond, the audience sees a close up of genitalia, or something else of that general X-rated nature. But since the images come and go so quickly, the audience's brains don't quite process what has just occurred. They continue their movie-viewing experience confused and disturbed any have no idea why.

In the final scene of "Fight Club," as The Narrator and Marla gaze at each other lovingly while civilization collapses all around them amid the aura of Pixies' essential indie anthem "Where is My Mind," slow the speed down a few frames. See if you notice a penis. You should, because there's a penis spliced into the end of "Fight Club."

Yup, even a hummingbird couldn't catch this movie at work. Which might be why people are still talking about it after all these years.