Who Really Created The Most Iconic Superheroes

If you've never read a comic book, seen a superhero movie, or watched a Marvel or DC-derived TV show, you've probably heard of at least a few; it's hard to go anywhere these days without bumping into some mention of Superman, Captain America, or Iron Man, among a growing list of others. But even if you're a huge comics fan, there's still a pretty good chance you don't know who created those characters—which is why we delved into the history of the medium to bring you the secret histories of some of the world's biggest superheroes.

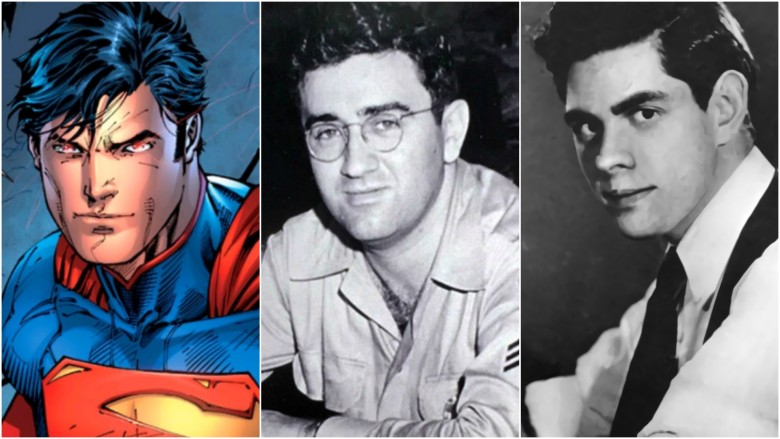

Superman - Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster

One of the world's first superheroes, Superman debuted in June 1938 in Action Comics #1. Writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster created the character and sold him to Detective Comics for a measly $130 after failing to find a buyer for the better part of the '30s. Perhaps it was their young age, or perhaps it was because costumed superheroes hadn't taken off yet. Still, there's no denying Siegel and Shuster created arguably the world's most iconic superhero.

Although Superman didn't first appear until 1938, his conception started five years prior, in Siegel's self-published short story The Reign of the Superman, with his friend Shuster drawing the villainous Superman. Whereas that version of the character was a villain, it set the foundation for what became the Man of Steel we know and love.

When Siegel and Shuster created the original draft of Superman in 1933, they were teenagers living in the Glenville neighborhood of Cleveland, OH, during the height of the Great Depression. They met each other at Glenville High School, a connection Siegel once described as "the right chemicals coming together," according to Roger Stern in Superman: The Sunday Classics: 1939—1943. Whereas Siegel was born and raised in Cleveland, Shuster was a Canadian immigrant, whose family moved to Ohio when Shuster was about ten years old. As teenagers, the two officially joined the comic book industry working for National Allied Publications, writing and drawing the company's New Fun Comics. But after Superman debuted in 1939, their lives changed—and they became legends in the comic book world. They both remained active members of the industry until their deaths in the '90s (Shuster in 1992, and Siegel in 1996).

There was never any controversy regarding who created Superman, but after seeing a character they'd sold for a pittance become a global icon, the Siegels and Shusters battled DC (and eventual parent company Warner Bros.) for decades, seeking additional compensation before finally resolving the case in 2013, with the courts favoring DC over Siegel and Shuster's heirs.

Batman - Bob Kane and Bill Finger

The Caped Crusader. The Dark Knight. The Batman—the world's greatest detective. Created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger, Batman debuted in Detective Comics #27 in 1939. He quickly became one of the industry's most famous superheroes, but unfortunately, for years all the appreciation for the creation of Batman went to Kane and not Finger.

According to The Steranko History of Comics, Kane hired Finger—a poor shoe salesman with comic book aspirations from Denver, CO, who met Kane at a high school reunion party—as a ghost writer, and together they molded Kane's original concept of Batman into the character we know today. And that was the issue: Kane, a New Yorker who went to school with comic book legend Will Eisner, believed "the trouble with being a 'ghost' writer or artist is that you must remain rather anonymously without credit. However, if one wants the 'credit,' then one has to cease being a 'ghost' or follower and become a leader or innovator."

Even though the comic book community has always recognized Finger's contributions in creating Batman, it's something Kane only admitted to many years later—in his autobiography Batman and Me, of all places. He credited Finger, 15 years after Finger's death, with giving Batman a gray suit, a hood, slit-cut eyes, a cape, and gloves, instead of Kane's original idea of a red-and-black suit, a domino mask, trunks, and wings. But that's not all. Jerry Robinson, who worked with Kane and Finger, said Finger was responsible for Batman's identity too. "I felt that I was part of a team. Unfortunately, Bob did not feel that way, most of all with Bill. He should have credited Bill as co-creator, because I know; I was there...He was very innovative. The slogans—the Dynamic Duo and Gotham City—it was all Bill Finger."

Despite community outrage, DC Comics only credited Kane. It wasn't until Batman's 75th anniversary in 2014 that the publisher finally announced they'd credit Finger from then on. And to mark the announcement (and the occasion), DC released a special free printing of Batman's debut, Detective Comics #27, with both Kane and Finger receiving credit. The change doesn't only apply to comics; it applies to all forms of media. One simply needs to look at the credits in both The Dark Knight Rises and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice to notice the difference.

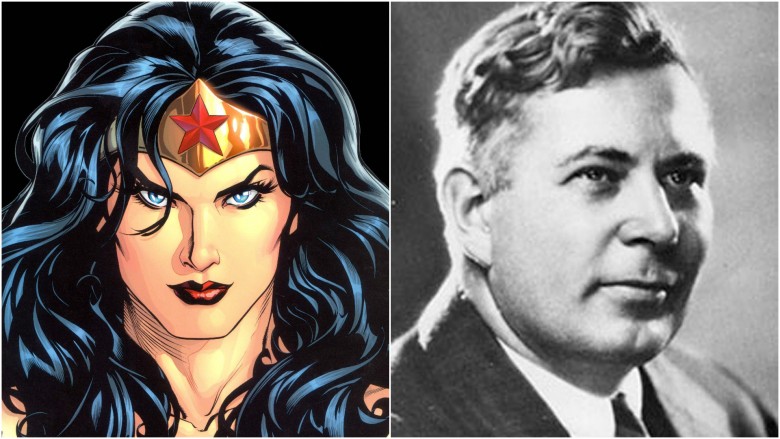

Wonder Woman - William Moulton Marston

Wonder Woman isn't just one of the world's first female superheroes; she's regarded as a feminist icon, one that the United Nations granted honorary ambassadorship for the Empowerment of Women and Girls in 2016 (until an online petition prompted them to revoke it). It only makes sense for Wonder Woman to carry such a title, since her creator, William Moulton Marston, was also a self-proclaimed staunch feminist.

As a Ph.D. graduate from Harvard, Marston came from a background in psychology and education. He worked in the psychology departments of both American and Tufts universities—not exactly someone who you'd expect to see creating an iconic superhero. But Marston believed comics needed someone to combat the "blood-curdling masculinity" found in the medium at the time, and wanted to create a character that could strive on a foundation of love and not sheer brutality (or merely the use of gadgets, in Batman's case).

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Marston's career prior to creating Wonder Woman is his work in developing the lie detector test. He created the systolic blood pressure test, a key component in John Larson's polygraph. Though unconfirmed, many fans and historians believe Marston took inspiration from the polygraph test for Wonder Woman's iconic Lasso of Truth. Marston may get all the credit for his work, but he wouldn't have gotten as far without the help of his wife, Elizabeth Holloway Marston, his unofficial partner and muse—and the one who convinced Marston to make the character a woman in the first place.

In 1947, just a few years after Wonder Woman debuted in All-Star Comics in 1941, Marston died of cancer—but his legacy clearly continues to live on. And despite the fact that he was never directly associated with the industry, DC recognized Marston's contribution to their success by honoring him in the Fifty Who Made DC Great publication that celebrated the company's 50th anniversary.

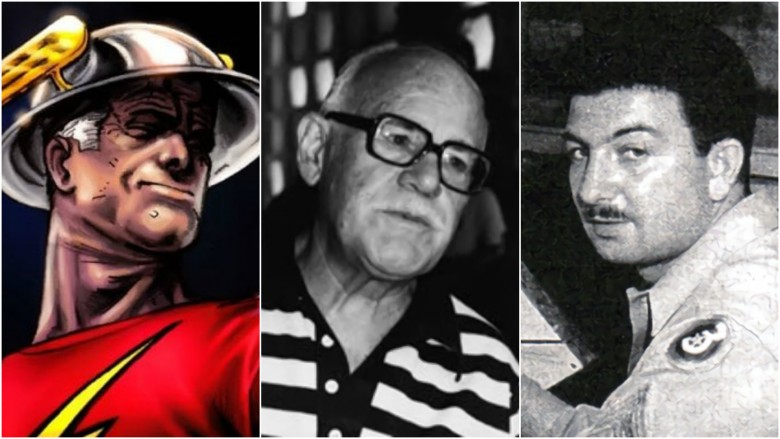

Flash - Gardner Fox and Harry Lampert

Most of the world's most iconic superheroes have consistently had the same alter ego, but the Flash is an exception. Multiple characters have been the Flash, and make up the so-called Flash Family, but it all had to start somewhere—and that somewhere was with Jay Garrick, the Golden Age Flash who debuted in Flash Comics #1 in 1940, by writer Gardner Fox and artist Harry Lampert.

Fox, a Brooklyn-native and graduate of St. Johns University, practiced law in New York for two years before realizing that the Great Depression had made his career unsustainable. Under the advice of his longtime friend and National Allied Publications editor Vin Sullivan, he turned to comics and started contributing to virtually every series in DC's lineup. He began his career as a contributor, but his decades-long career would eventually reshape the industry.

Lampert, on the other hand, a native New Yorker and cartoonist, turned away from superhero comics early on. Paid $10 a page for Flash Comics, he left after only a handful of issues, then spent the rest of his career drawing cartoons like The King and Red and White and Blue, among others. Strangely, Lampert didn't know how beloved he was among comic book readers and collectors until the '90s, when a friend informed him about his fame. The next year he took a trip to San Diego for Comic-Con. "There I was hailed," Lampert told the Washington Post in 1996. "I couldn't believe it. I was on this panel. People were coming up to me for autographs!"

Despite Lampert's early departure, Fox carried on with Flash Comics and eventually moved on to other heroes (and other publishers). But perhaps his most crucial contribution—to not only DC, but the industry as a whole—was the concept of a multiverse. With his Flash of Two Worlds! comic, he introduced the idea of multiple Earths by bringing the original Flash into the Silver Age.

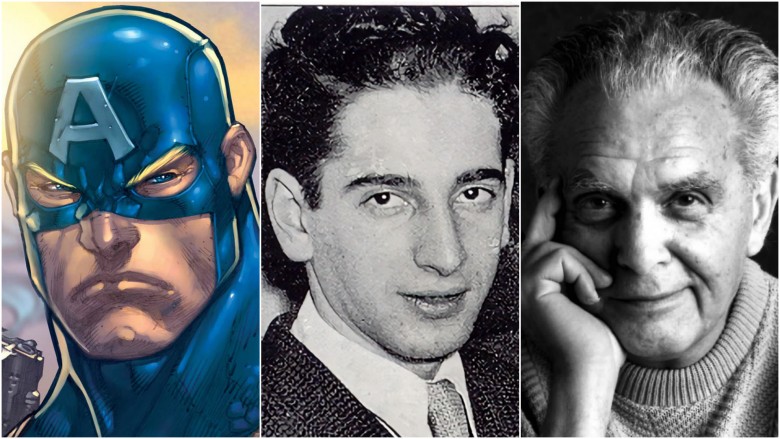

Captain America - Joe Simon and Jack Kirby

Long before the development of Marvel and its famed slate of superheroes, cartoonists Joe Simon and Jack Kirby led the charge with three characters during their tenure running the company's precursor, Timely Comics: The Human Torch (not to be confused with the Fantastic Four's Human Torch), Namor the Sub-Mariner, and Captain America—the latter of whom debuted in Captain America Comics #1 in 1941 punching Adolf Hitler in the face, and quickly became one of the most popular superheroes ever created.

Simon, born in Rochester, NY, got his start working in the art departments of various newspapers in the area. After moving to New York City, he started working for Paramount Pictures, retouching celebrity photographs. "I retouched some of the most famous bosoms in motion pictures—Gloria Swanson, Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Carole Lombard and Dorothy Lamour," he later quipped. But the movie industry wasn't for him, so he took a job at Fox Comics, where he met his future collaborator Jack Kirby.

Kirby, a New York native, grew up poor on the Lower East Side surrounded by gangs and other immigrant families. Though fighting was unavoidable, Kirby said his out was reading pulp magazines and comic strips. After attending Pratt Institute for no longer than a week, he left and taught himself how to draw—a pretty humble beginning for the guy widely regarded today as the King of Comics. He hopped around a bit from publisher to publisher until landing at Timely and working with Simon. Soon after, Kirby was drafted into the Army during WWII. And after having seen the concentration camps firsthand, he returned to the comic book industry with a fervor that identifiable in his work on Captain America, Red Skull, and even DC's Darkseid.

Kirby's unique contribution almost didn't happen. He said in his autobiography The Comic Book Creators that he planned to hire Al Avison and Al Gabriele to help Kirby pencil the first issue so they could make their deadline. But as Simon put it, Kirby told him, "'I'll make the deadline. I'll pencil it [all] myself and make the deadline.' I hadn't expected this kind of reaction...I acceded to Kirby's wishes and, it turned out, was lucky that I did. There might have been two Als, but there was only one Jack Kirby."

Though they got an early start in the industry, both Simon and Kirby worked in comics—or, at least, in some form of art—for the rest of their lives. Kirby passed away in 1994 due to heart failure, but Simon lived until 2011, just long enough to see Captain America make his debut in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

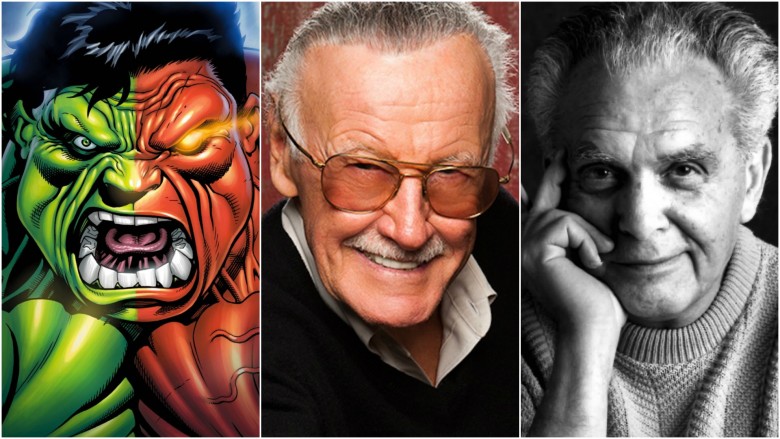

Hulk - Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

An unstable, green-skinned rampaging behemoth who came to life after scientist Bruce Banner was exposed to gamma radiation in an experiment gone wrong, the Hulk quickly stood out in the Marvel roster as a unique character in a sea of replicas—and readers had Stan Lee and Jack Kirby to thank.

Lee, born Stanley Martin Lieber grew up in New York during the Great Depression. Like many families during that time, Lee's parents hopped from apartment to apartment and job to job. "I was born of poor, but humble parents," Lee said in 2006. His family lived in "a third-floor apartment facing out back. I always wished it could have windows on the street. Mostly, I read a lot. Otherwise, I tried to get out." One of Lee's first jobs was working for Kirby and Joe Simon as an office boy. But since the duo had too much to write, they started giving Lee some work to do. And, well, the rest is history. "...they said, 'Hey Stan, you think you can write this?' When you're seventeen years old, what do you know? I said, 'Sure, I can do it!' And that was it."

He may not be running Marvel anymore, but Lee has maintained an active presence in the comic book and entertainment industries. Aside from his humorous cameos in Marvel films, Lee founded the Stan Lee Foundation in 2010 to support literacy programs across the United States as well as create the Comikaze Expo, Los Angeles' biggest comic book convention in 2011. Though many of Lee's friends and collaborators have since passed away, he's still going strong—in fact, he recently celebrated his 94th birthday.

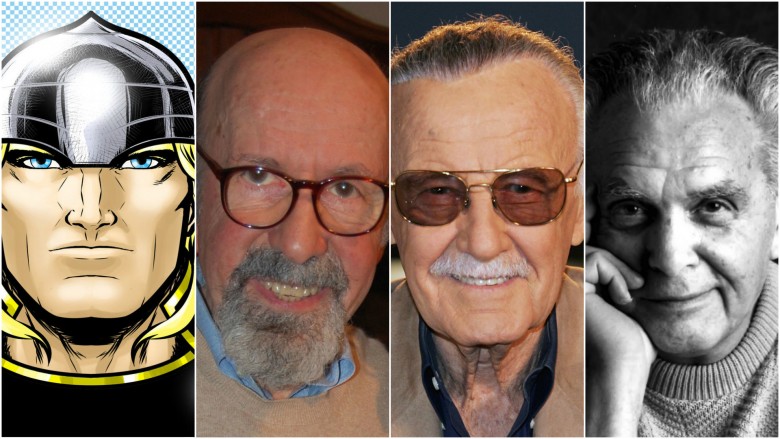

Thor - Larry Lieber, Stan Lee, and Jack Kirby

Thor is unique because he isn't just a superhero—he's a god. He comes from the Norse mythology from which Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, and Jack Kirby drew their inspiration when they created a version of the ancient god for 1962's Journey into Mystery #83. Lee, who was running Marvel at the time, assigned his brother Lieber to script the issue, with Kirby penciling.

Unlike his older brother, Lieber didn't immediately jump into the world of comics. Though he was always interested in drawing (and was even good at it), he didn't get into the High School of Music and Art as he wanted, so after graduating high school, he joined the Air Force during the Korean War. After his stint was done, he started working for Magazine Management, the company that owned Timely Comics. It was through his work with Magazine Management that Lieber started working with his brother at Marvel. "Stan made up the plot, and then he'd give it to me, and I'd write the script," Lieber said of his work routine. He must enjoy it—he's still doing it as of this writing, penciling Spider-Man comic strips past his 80th birthday.

As for Thor, it's hard to say who actually came up with the idea for the character, though there's no denying all three played an integral role. In his autobiography, Excelsior!: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee, Lee explains that shortly after creating the Hulk, he wanted to create a character who could be stronger. The only way that would be possible was to make a god, and thus Thor was born. "After writing an outline depicting the story and the characters I had in mind," he recalled, "I asked my brother, Larry, to write the script because I didn't have time."

It only made sense for Lee to assign Kirby as the artist, because he was an avid enthusiast of the ancient gods—in fact, he'd done a version of Thor for DC in the '50s. "He had a red beard, but he was a legendary figure, which I liked. I liked the figure of Thor at DC, and I created Thor at Marvel because I was forever enamored of legends," said Kirby. "I knew all about these legends which is why I knew about Balder, Heimdall, and Odin. I tried to update Thor and put him in a superhero costume. He looked great in it, and everybody loved him, but he was still Thor."

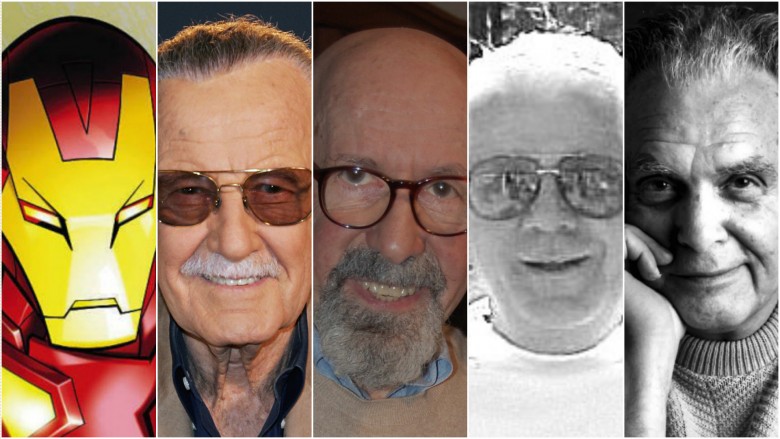

Iron Man - Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, Don Heck, and Jack Kirby

Thanks to Robert Downey, Jr. and the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Iron Man might be the most popular Marvel character in the world—every movie since The Avengers starring Iron Man has grossed over $1 billion worldwide, after all. The fact is, Iron Man, who debuted in Tales of Suspense #39 in 1963, wouldn't exist without the work of Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, Don Heck, and Jack Kirby.

Lee, inspired by the eccentric Howard Hughes, wanted to create a new type of superhero, one who'd go against the archetypes Marvel readers were used to. "I think I gave myself a dare. It was the height of the Cold War," Lee said. "The readers, the young readers, if there was one thing they hated, it was war, it was the military. So I got a hero who represented that to the hundredth degree. He was a weapons manufacturer, he was providing weapons for the Army, he was rich, he was an industrialist. I thought it would be fun to take the kind of character that nobody would like, none of our readers would like, and shove him down their throats and make them like him. ... And he became very popular."

Generally at the time, Lee worked up the plot and handed the reins over to Lieber, who wrote the script, and Kirby would design the character and draw out the cover. But this time, instead of Kirby penciling the entire issue, the team had Heck join them as the story artist.

Born in 1929, Heck grew up in the Jamaica neighborhood of Queens, NY, during the Great Depression. Although he didn't get his start in the industry until he was 20, Heck said his interest started when he was about five or six, when he tried to draw Donald Duck. If it wasn't for a college friend who turned him on to Harvey Publications, Heck's career might have been very different: he interviewed and worked for the publisher for over two years before moving into freelance work for companies like Quality Comics, Hillman Comics, and eventually Atlas Comics (a successor to Timely, but the predecessor to Marvel). After meeting Lee, Heck started working at Atlas on September 1, 1954, where he'd go on to create Iron Man nine years later.

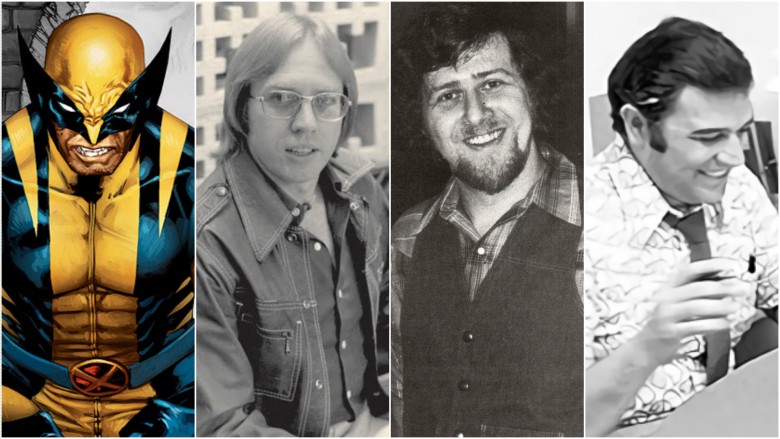

Wolverine - Roy Thomas, Len Wein, and John Romita

There's no denying that Hugh Jackman made his mark on Wolverine, arguably the most famous of the X-Men. But Jackman only modeled his take on the character based on ideas Wolverine's creators—Roy Thomas, Len Wein, and John Romita—conceived decades ago. Wolverine, a mutant, is known for his retractable claws and unparalleled healing factor, but sometimes people tend to forget that the character is actually Canadian, not American—and that was intentional. First appearing in The Incredible Hulk #180 in 1974, Wolverine quickly became a prominent member of the X-Men—and Marvel Comics as a whole.

Thomas, born in Jackson, MO, in 1940, was an avid comic book reader, a hobby he maintained throughout his life. Shortly after graduating from college in 1961, he purchased his first Marvel comic, Fantastic Four #1, and fell in love. Four years later, Lee hired him as a staff writer and he worked his way up the ranks. In the early '70s, when Lee became Marvel's publisher, Thomas succeeded him as Editor-in-Chief, and one of his first acts as the new big boss was to have his writer, Wein, create a new Canadian hero called Wolverine.

Not much is known about Wein's early life, except for the fact that he was "a sickly kid." He was hospitalized at seven years old, and his father brought him a stack of comic books, sparking his love for the medium. He spent his school and college years studying art and mastering a craft he'd use over a long career that included stints at Marvel and DC—and included the creation of Wolverine, a character he believes is his most financially successful work.

After being tasked with Wolverine, Wein assigned Marvel's then-art director, John Romita, with designing the character. Romita, born in Brooklyn in 1930, attended the School of Industrial Art as a teenager, but his love for drawing started when he was only five. In junior high, he'd draw the scenery and background for his school's plays. He got his start in the industry penciling for Lester Zakarin, whom he'd known from his school days. He's a comics legend—but funnily enough, his only regret is that he wasn't born a decade earlier. He always wanted to be among the comic book greats of the late '30s and '40s.

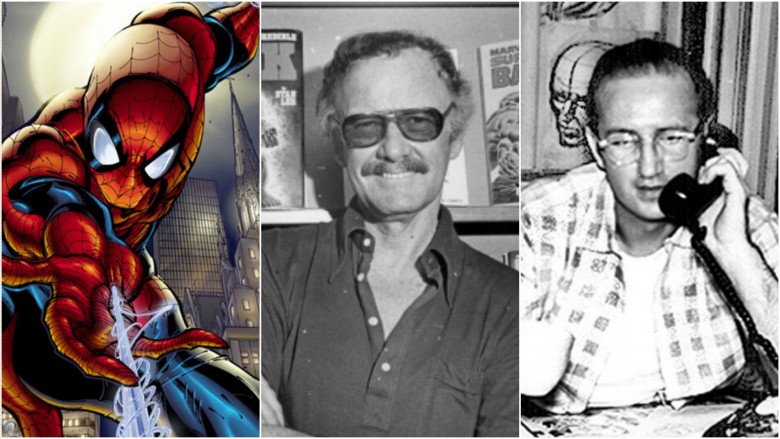

Spider-Man - Stan Lee and Steve Ditko

Spider-Man, created by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, made his debut in Amazing Fantasy #15 in 1962, and has become arguably the most iconic Marvel superhero. Much of his popularity is due to his relatability with young readers, particularly young boys. He started out as a quirky, poor kid from Queens who spends most of his time stressing about school and money—what's not to relate to? And unlike most other superheroes, Spider-Man grew into his abilities on his own, without a mentor or sidekick. Lee turned to his frequent collaborator, Jack Kirby, to flesh out the character, but for some reason or another, Lee didn't like what Kirby was doing. So he turned to Ditko instead.

"One of the first things I did was to work up a costume. A vital, visual part of the character. I had to know how he looked...before I did any breakdowns," Ditko said in an essay. "For example: A clinging power so he wouldn't have hard shoes or boots, a hidden wrist-shooter versus a web gun and holster, etc." Ditko, born in Pennsylvania, studied at New York's Cartoonists and Illustrators School under the tutelage of Batman illustrator Jerry Robinson, but not before enlisting in the Army at the tail end of WWII. Not long after being discharged from the Army, Ditko suffered from tuberculosis. After a yearlong recovery, he launched into a hot streak in comics beginning with Charlton Comics and later Marvel.

Unlike most of the other creators from the Golden and Silver ages, Ditko no longer works in the industry, nor is he an avid member of the comic book community. Rather, he's a recluse; according to Vulture, his most recent published photograph was taken almost 50 years ago. In fact, he hasn't conducted an interview since 1969, only a few years after his sudden departure from Marvel in 1966. Still, Ditko remains revered among comics fans and collectors for his work on Spider-Man, Doctor Strange, and Captain Atom, among other characters and stories. Though there's some confusion over whether Ditko or Kirby deserves credit for drawing the first Spider-Man cover, there's no confusion over who actually created the character.