The Ending Of Places In The Heart Explained

They're mostly remembered for producing a plethora of highly popular horror, comedy, and action-adventure flicks, but the '80s were also a kind of golden age for prestige family dramas in U.S. cinema. These star-studded, self-effacing, humanist-tinged stories of everyday Americans formed, along with sturdy historical epics and timely social-issue films, the tripod of "respectable" cinema — colloquially known as Oscar bait. These are films that filled the mid-budget adult-oriented bracket in parallel with the rise of the modern blockbuster.

Many of those once-acclaimed family dramas have been somewhat forgotten, as they appealed very specifically — arguably even more than horror movies or comedies — to the reigning cinematic sensibilities of the time. But they do have legacies, and that's very much the case of 1984's "Places in the Heart." Even if this Robert Benton-directed story of community and perseverance during the Great Depression isn't exactly a hot topic nowadays, you're all but guaranteed to know of two things about it. The first is that it spurred star Sally Field's iconic "You like me!" moment at the Oscars, where she won for Best Actress. Second, it featured one of the most unexpected and talked-about endings in '80s cinema, one which still packs a wallop to this day.

Places in the Heart's ending embodied the liberal values of its era

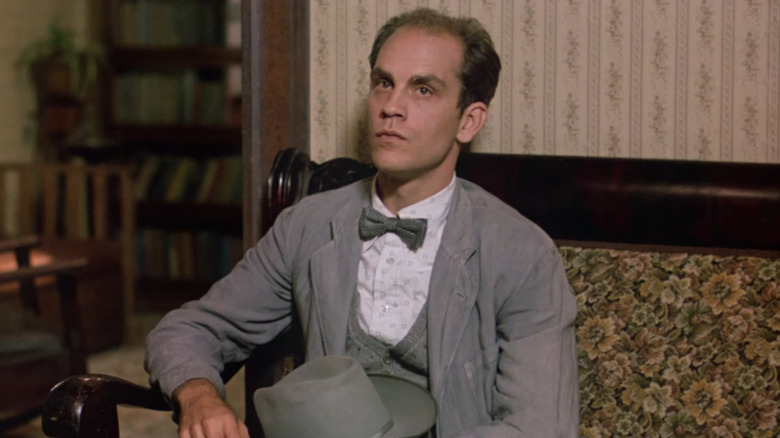

Before we get to the famous final scene, we have to go over how the movie gets there. Like many family dramas of its ilk, "Places in the Heart" is less concerned with its own overarching plot than with its characters. For most of the movie, Edna Spalding's (portrayed by Sally Field, in one of her best movie roles) goal to save her farm takes a backseat to the fleshing out of her relationships with sister Margaret (Lindsay Crouse), Black right-hand man Moze (Danny Glover), and blind lodger Mr. Will (John Malkovich, in a role fans likely forgot about), among others.

Then, in the movie's climax, Edna and Moze join forces and hire 10 more people in a desperate bid to earn a local $100 prize, which will be given in exchange for the year's first bale of cotton to be picked. It's a last-ditch effort that ultimately succeeds in grand crowd-pleasing fashion, leaving Edna and Moze worn out, full of bruises on their hands, yet feeling victorious. But things take a turn when a group of Ku Klux Klansmen ambushes Moze at the farm, beating him badly until Mr. Will drives them off.

This denouement expresses the liberal worldview espoused by most respectable Hollywood fare at the time. Hard work saves the destitute, and, though there is a condemnation of racism, it's pitched toward a white audience whose relationship to the issue is primarily emotional. Moze "earns" sympathy by proving useful and loyal to Edna, so that his beating becomes tragic in the context of the character drama — the political subtext being that his fate is unfair because he worked just as hard as everyone else. This couching in traditional American values allows the movie to be "important" while remaining agreeable.

The final scene reveals that the movie has more on its mind

You might think "Places in the Heart" would be remembered as an example of the inoffensive pablum that so many Best Picture nominees from that era seem to boil down to. But as mentioned before, it does have a legacy, chiefly as a result of its powerful finish.

After Moze leaves the farm to ward off his previous assailants, the movie segues into an epilogue at the local church. This much is par for the course for a Southern drama, but what comes after isn't. As the choir sings "In the Garden," Communion begins to be passed from person to person, and every previously seen character, living or dead, pops up to drink the wine and bless their neighbor. We close in on Edna's late husband, Royce (Ray Baker), and the Black boy who accidentally killed him and was subsequently lynched, Wylie (De'voreaux White), saying "Peace of God" to each other.

This last scene is striking not just because of its unexpected foray into the supernatural and metaphorical, but because it peddles a more complex message than the rest of the movie would seem to be building to. We leave the realm of liberal meritocracy and idealized social harmony and enter into a stringently Christian allegory for the promise of holy respite, in which, no matter what they've done or gone through, people are forgiven and met with peace and love. At this moment, the movie shows that it understands just how harsh the realities of poverty and racism are. This suggests that the film intends not to sugarcoat these issues but to demonstrate their connection to the role of faith in the South while asserting, as the Bible does, that there is hope for everyone.