Weird Children's Movies From Your Parents' Childhood

It seems like every generation believes their entertainment is far better than what came before it and what came after, doesn't it? Kid-friendly movies and TV is no exception: how many times have you restrained an eyeroll while your parents or even grandparents explain to you why their Saturday morning cartoons or Disney feature animation or anime put the junk you watched to shame? It's enough to warrant an "Ok boomer."

Nostalgia has a heavy hand in these Gen X declarations, just as it does when Gen Z members recall their favorite kid-vids. We all feel warm and fuzzy for the programming we enjoyed over a bowl of sugar cereal, and older folks (we're talking 40+) are no exception. Waxing rhapsodic about the "Pac-Man" cartoon or "Captain Planet" is a fun way to stay connected to your past. The only problem is that when the filter of nostalgia is lifted away, a lot of what your parents and their parents watched was, well, pretty weird.

We're not saying it's worse than current children's entertainment. We'd just like you to take a look at the following list of kids' features from the 1950s to 1980s and consider, if you will, the peculiarities of what passed as a fun afternoon back in the day.

You might not want to know The Secret of Magic Island

Spoiler alert: The secret part of "The Secret of Magic Island," as depicted in this 1956 French-Italian feature, is that it's populated entirely by animals, who spend their day engaged in human activities. A puppy takes music lessons from a cat, a duck delivers the mail, and everyone seems beyond excited — at least, that's what the omnipresent narrator tells us — about the impending arrival of the carnival. Everyone, that is, except for the Black Troll, a monkey whose unrequited love for a fairy has spurred him to steal and use a magic wand in order to ruin everyone's fun.

Directed by Jean Tourane (a former photographer turned filmmaker who specialized in anthropomorphic antics featuring animal performers), "The Secret of Magic Island" straddles an uncomfortable line between ingenuity and exploitation. Yes, the film does showcase some impressive set pieces to illustrate the animals' lives — the carnival, in particular, features your chance to see frogs on motorcycles — but it's also hard to shake the nagging idea that said animals were not at all thrilled about carrying out their on-screen tasks, like the fox shampooing a chicken's head or the rabbit smoking a cigarette.

The film's hero, a duckling named Saturnine, was featured in two '50s-era shorts directed by Tourane, and later earned its own television series, "The Adventures of Saturnin," which ran on French television from 1965-1968. They were later edited into interstitial bumpers and shorts on the Fox Kids network in the early '90s under the title "The Adventures of Dynamo Duck," with Dan Castellaneta providing the voice for the title character.

Little Red Riding Hood and the Monsters: fairy tale ... or nightmare?

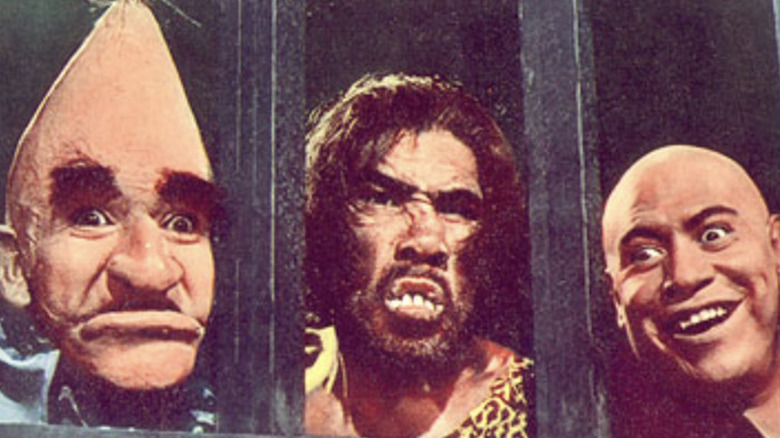

The third and most deranged Mexican fantasy film centered around child actress Maria Gracia as the titular fairy tale heroine, 1962's "Little Red Riding Hood and the Monsters" represents a sort of "Avengers: Endgame" for the Peliculas Rodriguez production company, which oversaw a great deal of kiddie fantasy fare from Mexico in the 1960s (as well as lucha libre and horror titles). Here, Gracia is joined by not only Tom Thumb (Caesar Quezadas) and his nemesis, the Ogre (Jose Elias Moreno) from 1958's "Pulgarcito," but also the Wolf (Manuel "Loco" Valdes) and a particularly irritating Skunk (Santanon) from the previous "Red" films, both depicted with horrifying costumes that feature far too much of the actors' faces.

This super team is pitted against the Witch Queen (Ofealia Guilmain, tricked out as an unauthorized Evil Queen from "Snow White") and her minions, a bizarro ensemble that features both traditional movie creeps (the Frankenstein monster) and original creations, including a squabbling conjoined creature, a pointy-headed thug with a Super Mario mustache, and a robot, for good measure.

This unholy crew, which feels like something a child might draw after a strong tablespoon of cough medicine, abuses the Wolf and Ogre at length (even waterboarding them) for turning their backs on their bad guy pasts until Red, Tom, and the Skunk mount a rescue mission.

The original Mexican version is threadbare but well-intentioned kids' fare, but the American dub and edit, overseen by distributor K. Gordon Murray (who gave us the astonishing Mexican "Santa Claus," with Moreno as St. Nick), is awash in ranting dialogue and nonsensical music numbers, delivered with headache-inducing performances. For 21st century kids, the effect is likely to be as delirious as those who were dragged to see it in Saturday afternoon matinees in the early 1960s.

The Cassandra Cat: Kid's movie as political commentary

At once imaginative and psychedelic, the 1963 Czech fantasy and Cannes Jury Prize winner "The Cassandra Cat" (alternately known as "That Cat" and "When the Cat Comes") also lampoons, in the oddest way possible, the Communist strongmen who held Czechoslovakia and other Eastern European countries in their grip during the 1960s. The Red stand-in here is a mean-spirited principal (Jiri Slovak) with an appetite for taxidermy, while the proletariat class is represented by Vlastimil Brodsky's kindly art teacher.

Facilitating Robert's transformation from meek worker to freedom fighter (of sorts) is the titular cat, a member of a traveling circus that reveals people's true natures once its eyeglasses (!) are removed. Spiteful and underhanded types appear bathed in bright yellows or mournful grey, while Robert is a bold red. A freeform dance/freakout ensues, followed by the principal's pursuit of the cat for his trophy collection while the local children defend it. Read any and all political commentary into that description as you see fit.

The color and dance sequences in "Cassandra" are striking and surreal, but never exceed the wistful and magical tone that director Vojtech Jasny establishes in its opening sequences, where town elder Jan Werich lays out the local conflict in kindly but knowing terms. The effects can't help but look low-tech for 21st century kid viewers, but adults may find it hard to resist an anti-authoritarian revolt led by a cat in spectacles.

Jimmy, the Boy Wonder is anything but wonderful

Herschell Gordon Lewis, who created some of the grossest, gloppiest horror movies of the 1960s, including "Blood Feast" and "Two Thousand Maniacs!" occasionally took a break from dismembering his actors and ventured into other genres. The majority of these were exploitation films like "She-Devils on Wheels," but on two occasions, Lewis tried his hand at children's entertainment. And while no one loses a limb in the resulting efforts — 1966's "Jimmy, the Boy Wonder" and "The Magic Land of Mother Goose" — both are head-scratching experiences.

"Mother Goose" is a filmed version of a live magic show with a fairy tale theme, and while awkward, it can't hold a candle to the sheer oddity that is "Jimmy the Boy Wonder." Antsy, mumbling child actor Dennis Jones plays the title role, whose less-than-wondrous need to blow off his minimal responsibilities leads to a wish for time to stop; noting that Jimmy's laziness has brought existence to a standstill, an astronomer sends his daughter (Nancy Jo Berg) to help the little pill fix the "master clock" and get life back on track.

Opposing them is Mr. Fig (David Blight, Jr.), a villain with colossal painted eyebrows and an attitude towards Jimmy that borders on predatory. Much of the film's running time is devoted to Fig chewing the limited scenery or Jones and Berg shuffling listlessly from one scenario to another. To slow down the action even further, Lewis inserts a wholly unrelated cartoon into the mix, even providing several of the voices (he also narrates). If you're still watching by the time Jimmy reaches the master clock, consider yourself a hardy moviegoer indeed.

The Lemon Grove Kids Meet the Monsters: Backyard moviemaking for grown-ups

It might be one of the earliest examples of a fan film: "The Lemon Grove Kids Meet the Monsters" is a trio of ultra-low-budget shorts, made between 1965 and 1968 and stitched into a single feature that oddly enough pays tribute to the long-running Bowery Boys series of comedy features from the 1940s and 1950s.

The director and star here is Ray Dennis Steckler, a doggedly independent filmmaker who never let a lack of funding get in the way of a good (or weird) idea. Steckler's probably best known for the freewheeling horror-musical "The Incredible Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies," but his entire CV is filled with eccentric and entertaining features.

For "Lemon Grove Kids," Steckler simply rounded up his friends and family — wife Carolyn Brandt, their daughters, neighbors, and a few moviemaking pals like editor Keith A. Wester, who later earned six Oscar nominations for sound — and turned them loose in his neighborhood to face mummies, aliens, a vampire (Brandt) and kidnappers. Their antics are strictly Saturday morning cartoon fare (if you find undercranking funny, this is the movie for you), but the fun the cast appears to be having is frequently infectious.

All Monsters Attack and you should retreat

In an attempt to stave off the declining revenue plaguing the Japanese film industry in the late 1960s, Toho began marketing their most popular franchise — Godzilla — directly to children.

The Toho Champion Festival debuted in 1969 with a package that bundled a live-action comedy and cartoon with a brand new Godzilla adventure called "All Monsters Attack," which focused on a young boy and his imaginary friendship with Godzilla's offspring, Minilla (or Minya).

On paper, "Attack" — which played in the States as "Godzilla's Revenge" — sounds like a kaiju kid's dream come true. Who wouldn't want to be pals with Minya? Well, as it unspools in the film, helmed by longtime Godzilla director Ishiro Honda, the answer is: pretty much no one. "Attack" is a resolutely depressing film, both in subject matter and execution. Its kid hero, Ichiro, is ignored by his parents and bullied by classmates, and finds comfort only in dreams involving Minya.

Unfortunately, the misery doesn't end there for either Ichiro or the viewer. The stiff, lumpy Minya (who's saddled with a grating voice in the English dub) is just as much of an outcast as Ichiro, and suffers constant indignities at the hands of various Monster Island occupants (all featured in recycled stock footage) and a new creature, the jabbering Gabara. The only way Minya can win his largely absent parent's approval is to play dirty — which is exactly how Ichiro wins over his bullies in the real world. Toho would offer a more enjoyable kid-oriented Godzilla film with 1973's "Godzilla vs. Megalon," which features the ridiculously cool robot Jet Jaguar.

Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny are gifts you'll want to return

Stranded in the sand of a Florida beach, a noticeably slim Santa (Jay Ripley/Jay Clark) sweats and complains at length in the opening moments of 1972's "Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny" until summoning, via telepathy, several local children (and Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn) for help. The kids attempt to fix Santa's problem with various animals — a pig, donkey, and a guy in a gorilla suit — but fail to extract his sleigh from what appears to be an inch of fine-grain sand.

Attempting to rally his unpaid help, Santa tells them a story, and depending on which version of "Ice Cream Bunny" you're watching (yes, there are two), the viewer is treated to a feature-length, stagebound version of "Thumbelina," or a condensed version of "Jack and the Beanstalk." Both were previously released films directed by "Ice Cream Bunny" producer Barry Mahon, whose usual fare hewed towards adults-only material, while the footage of Tom and Huck was apparently part of an uncompleted project.

For the record, "Beanstalk" is weak tea, burdened by atrocious songs and primitive special effects, while "Thumbelina" is desperately strange, and features a scene in which the title character is propositioned by a humanoid mole.

Back in Florida, Santa exhausts himself telling the story and falls asleep, only to be awakened by the sound of a fire engine, which is piloted by the Ice Cream Bunny. Its relationship to ice cream is never explained, but the creature, its face locked in a toothy perma-leer, does give St. Nick a lift back to the North Pole. Christmas is saved! But not your grip on your sanity.

Call it Dogzilla: Digby, the Biggest Dog in the World

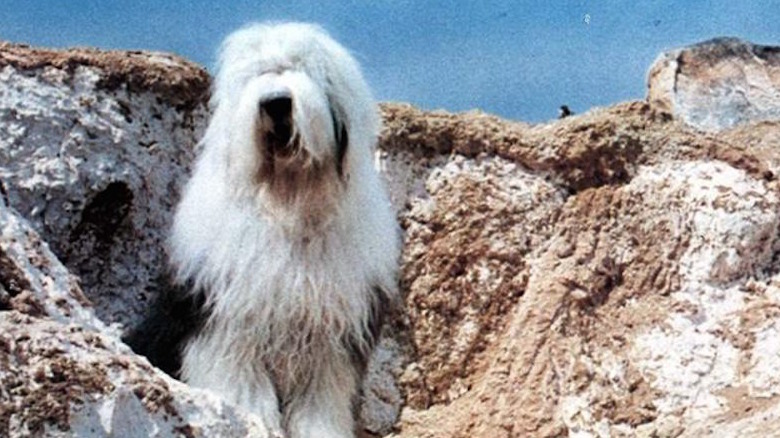

Actor Jim Dale, whose voice will be immediately recognizable to anyone who enjoyed the audio editions of the "Harry Potter" novels, is top-billed here as a dull-witted lab assistant whose theft of growth-enhancing plant food accidentally results in "Digby, the Biggest Dog in the World." Digby, the Old English Sheepdog that consumes the food, soon grows to colossal height, which attracts the attention of thieves who want to sell him to the circus, as well as the scientist (Spike Milligan) that created the food and the British military, who intend to halt his ceaseless growth with heavy artillery (!).

Needless to say, this 1973 feature does not include scenes of Digby tearing up London under a hail of missiles. You do get an awful lot of slapstick and far too little of Milligan, an anarchic force of nature who co-created the legendary "Goon Show" radio series which co-starred Peter Sellers, and wrote numerous plays, television programs, and features.

Director Joseph McGrath later directed scenes featuring Sellers in the 1967 version of "Casino Royale," as well as five promotional music videos featuring the Beatles, while screenwriter Michael Pertwee was a veteran of British TV and the brother of the Third Doctor, Jon Pertwee.

Return to Boggy Creek - that's not a request

Former TV commercial director and set decorator Charles B. Pierce scored a huge and surprising hit in 1973 with "The Legend of Boggy Creek," a feature about the Fouke Monster, a Bigfoot-like cryptid in Arkansas.

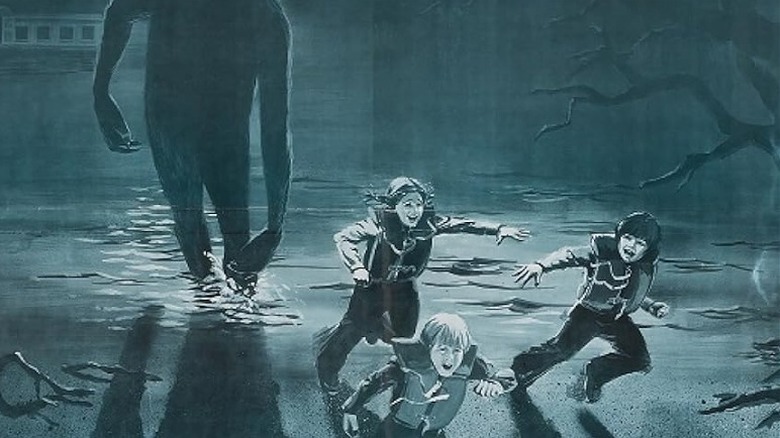

Pierce's film netted about $20 million at the box office, which naturally prompted a sequel. Some of the producers forged ahead without Pierce and generated "Return to Boggy Creek," which as its one-sheet proudly noted, was a "G-rated adventure for the whole family."

Unfortunately, "Return" is also a phenomenally dull movie, shorn of Pierce's knack for atmosphere and documentary-style depictions of the monster's interactions with humans. Here, we follow three kids (including Dana Plato from "Diff'rent Strokes") into the Arkansas swamp in pursuit of an expedition to find the monster, only to run afoul of a hurricane. Dawn Wells of "Gilligan's Island" fame does well as the kids' worried mom — she appeared prior to this in Pierce's creepy slasher film "The Town That Dreaded Sundown" — but the rest of the running time is devoted to minor league scares and cornpone humor.

Pierce would finally relent and make "Boggy Creek II: And the Legend Continues," an official sequel in 1985. But as anyone who has seen Season 10 of "Mystery Science Theater 3000" can tell you, he should have left well enough alone.

UK TV faves the Wombles stumble in Wombling Free

The Wombles were furry, ecological-minded creatures in a series of UK children's books that rose to international fame courtesy of an animated series that aired on the BBC from 1973 to 1975. Their popularity extended to a live-action musical act that scored several Top 5 singles on the UK charts and a mountain of merchandise, which led to their feature film debut with "Wombling Free" in 1978.

The premise of the film stays true to the Womble formula (the mole-like creatures clean up trash left by humans in their home base of Wimbledon Common), adding some amusing parodies of classic Hollywood musicals. But what made the Wombles' adventures on TV work so well — namely, a five-minute running time — feels interminable in the feature, despite the best efforts of actor-turned-director Lionel Jeffries, who had scored a considerable hit with his 1970 film adaptation of the popular UK children's novel "The Railway Children."

Adding to the disconnect is the depiction of the Wombles, who on television were cute stop-motion puppets. For the film, they're portrayed by little person actors, including Kenny Baker of "Star Wars" and his "Time Bandits" co-star Jack Purvis. Their costumes have the stiff, blank-eyed look of Sid and Marty Krofft's cult creations like "H.R. Pufnstuf," and as such, inspire far more shivers than adoration.

C.H.O.M.P.S. means a robot dog that fights crime

Charged with creating a security device to reduce a crime wave, young inventor Wesley Eure (from the TV "Land of the Lost") creates "C.H.O.M.P.S.", the Canine Home Protection System, which turns out to be a cute talking robot dog equipped with super-powered hearing, X-ray vision, and an unfortunate tendency to smash through solid objects in order to thwart crooks. The mecha-mutt impresses Eure's boss (Conrad Bain from "Diff'rent Strokes") and his daughter (Valerie Bertinelli from "One Day at a Time"), but also draws the attention of a rival security company with designs on stealing C.H.O.M.P.S.

The result of a short-lived partnership between animation giants Hanna-Barbera and American International Pictures (which produced and distributed many legendary cult movies in the 1960s and 1970s), "C.H.O.M.P.S." was directed by Don Chaffey, whose credits include the 1963 "Jason and the Argonauts" and 1966's "One Million Years B.C.", which both featured the special effects creations of Ray Harryhausen. "C.H.O.M.P.S." is probably the least notable effort by all involved parties, a limp comedy loaded with H-B-styled cartoon antics, but you do get to see a Benji lookalike jump through a window.

Don't book a ticket on The Last Flight of Noah's Ark

As Walt Disney Studios itself notes in its own history, the 1980s were a difficult period. The company's live action and animated features released under its Walt Disney Productions umbrella were, for the most part, well-intentioned and even sometimes critically-praised efforts, but almost every one failed to connect with sizable audiences.

"Midnight Madness," "Condorman," "Trenchcoat" and "Something Wicked This Way Comes" were among the list of box office misfires defining the decade, until "Honey, I Shrunk the Kids" and "The Little Mermaid" finally began to reverse Disney's fortunes.

Many of Disney's '80s efforts are forgotten, even by aficionados of the studio's efforts. Case in point: "The Last Flight of Noah's Ark," a live-action adventure that disappeared without a trace following its release on a double bull with a reissue of "101 Dalmatians" in the summer of 1980. It's competently made and features a likable cast led by Elliott Gould, Ricky Schroeder and Genevieve Bujold, and what seems like an exciting premise in a race to transform a downed B-29 bomber into a raft in order to escape a deserted island.

Unfortunately, neither director Charles Jarrott — a Golden Globe winner for "Anne of the Thousand Days" in 1969 — nor three screenwriters could come up with anything compelling or entertaining with those elements. There are some cute animals, minor league suspense and a pair of "comic relief" Japanese soldiers who have been marooned on the island since World War II but the rest is rote fare that wouldn't fly as episodic TV.

Anna to the Infinite Power covers heavy subjects for kids' sci-fi

"Anna to the Infinite Power," which premiered on HBO in 1982, was a strange science fiction fantasy about a child prodigy who discovers that she's one of many clones created from a dead scientist. The film, produced by the company that created the '70s/'80s kids' omnibus series "Big Blue Marble," opens as a slice of pre-teen angst with bratty 12-year-old genius Anna (future soap star Martha Byrne), whose bad attitude and kleptomania drives her family to distraction.

When she sees a TV broadcast features a girl that appears to be her exact double, Anna discovers that she is a clone of a physicist and concentration camp survivor who died before completing an experiment to solve world hunger. From there, "Anna" turns into a fairly dark sci-fi drama about unorthodox science experiments and a plan to murder the other Anna clones.

Layering a kids' film with such heavy concepts leaves the final product feeling unbalanced, and director Robert Wiener (a TV vet who helmed episodes of "Star Trek: The Next Generation") struggles to bring energy to the production. It's neither kid-friendly nor adult-oriented, and as such, satisfies neither audience.

The Peanut Butter Solution: it's not for breakfast

What is "The Peanut Butter Solution," you ask? As depicted in this Canadian film from 1985, the delicious spread is part of a disgusting concoction delivered to young Matthew Mackay by a pair of ghosts (!) after a shock causes him to lose his hair. That, in and of itself, is weird enough for at least a half-dozen kids' movies, but "Peanut Butter" ups the ante on odd in what seems like 15-minute increments until reaching what is arguably the most bizarre climax of any film on this list.

The solution, it seems, does its job too well: Mackay's hair refuses to stop growing, even after being cut, which gets him booted from school — just in time to learn that the shorn hair is connected to a rash of child kidnappings (!!) orchestrated by his mad art teacher (Michel Malliot). Mackay is eventually abducted by the teacher and strapped into a machine where the other kidnapped kids are forced to create magic paintbrushes from his hair (insert as many exclamation points as needed).

What begins as a fitfully clever kids' fantasy slides headlong into disturbingly dark territory, which is made exponentially weirder by a tone that veers from broad comedy to more adult-minded material. Case in point for the latter: Mackay's friend Conrad ("Degrassi High" star Siluk Saysanasy) decides to up his teenage game by applying the hair-growth glop to a private area, with appropriately inappropriate results. Add a few early songs by Celine Dion, and you have ... well, we don't know what you have. At all.