These Are The Only Near-Perfect Thriller Movies According To Metacritic

When your pulse is pounding, your heart is in your throat, and you could cut the narrative tension with a knife, you know you're watching a thriller. Also called suspense films, these are movies that use time-honored cinematic techniques to keep viewers on the edge of their seats with their eyes glued to the screen. The thriller is also one of the most historically important genres in film history: Many of cinema's greatest innovations, which modern audiences take for granted, were developed for use in thrillers.

This is a big part of the reason why many of Metacritic's highest-rated thrillers are from the so-called Golden Age of Hollywood. These early thrillers represent a broad, foundational genre, intersecting with and influencing everything from war movies to science fiction — as this list of Metacritic's highest-rated thrillers confirms, modern thrillers are often mixed with other genres. So take a deep breath, steady your nerves, and remember that it's only a movie as we dive into the thriller films rated 95 and up on Metacritic.

Double Indemnity (1944)

Billy Wilder's film noir thriller "Double Indemnity" is the story of a woman named Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck), who decides to kill her husband for the life insurance policy and manages to convince an insurance salesman named Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) to help her do it. It all seems to be going well at first, but things get complicated for Phyllis and Walter when the latter's boss becomes suspicious about the death and tries to prove that it was murder.

"Double Indemnity" was a trailblazer in the thriller genre, influencing many a filmmaker in the years and decades that followed. In fact, many of the movies on this list owe it a debt of gratitude: Alfred Hitchcock once wrote, "Since 'Double Indemnity,' the two most important words in motion pictures are 'Billy' and 'Wilder.'" This seminal thriller was remade by director Jack Smight (best known for the Paul Newman thriller "Harper") in 1973, but the updated version can't hold a candle to the near-perfect original, which is as gripping today as it was back in the 1940s.

Don't Look Now (1973)

Based on a 1971 short story by Daphne du Maurier, the 1973 psychological thriller film "Don't Look Now" stars Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie as a married couple who move to Venice following the death of their daughter. Sutherland's John Baxter has been hired to restore a church in the famous Italian city. Things start getting weird after the couple encounter a seemingly clairvoyant woman who claims to have a message from their deceased daughter and John starts seeing things that he cannot explain.

"Don't Look Now" was released to generally positive reviews at the time, but it took a while for people to recognize Nicolas Roeg's terrifying thriller for what it is: A masterfully crafted and frequently terrifying exploration of grief. The veteran critic Roger Ebert was among those who changed his opinion on the picture. After revisiting the film in 2002, he wrote: "Few films so successfully put us inside the mind of a man who is trying to reason his way free from mounting terror."

Gravity (2013)

Alfonso Cuarón won the award for best achievement in directing for his 2013 space-set thriller "Gravity," which he also co-wrote and co-edited. It stars Sandra Bullock as astronaut Dr. Ryan Stone, a medical engineer and mission specialist who is desperately trying to find a way back to Earth following the destruction of her shuttle during her first space mission. As thrillers go it's on the contemplative side, but don't let that fool you — "Gravity" is a real nail-biter in places, made all the more memorable by the stunning visuals and the gripping performances of Bullock and George Clooney, who plays her ill-fated commander.

It's no secret that sci-fi movies often get things wrong about space. Some liberties were taken by Cuarón to make the story work, but, on the whole, "Gravity" is actually less science fiction and more science fact, with some real-life astronauts praising how accurate the film is. "There was a one of a kind wirecutter we used on one of my spacewalks and sure enough they had that wire cutter in the movie," Michael J. Massimino told Space Safety Magazine, and Buzz Aldrin also remarked on the realism in a review he penned for The Hollywood Reporter, saying: "I was so extravagantly impressed by the portrayal of the reality of zero gravity."

Mean Streets (1973)

The third feature film from Martin Scorsese, 1973's "Mean Streets" is the story of two young men living in the Little Italy neighborhood of New York City. Charlie Cappa (Harvey Keitel) is a devout Catholic who is struggling to reconcile the work he does for his Mafia-boss uncle with his religion. His life is complicated further by the reckless behavior of his friend John "Johnny Boy" Civello (Robert De Niro), who owes money to some dangerous loan sharks and doesn't seem to care about the repercussions of not paying it back.

Part crime thriller and part character study, "Mean Streets" is a raw, edge-of-your-seat movie that will hit you in the feels in some unexpected ways. It's the film that put Scorsese on the map, though you don't have to be a fan of the filmmaker's oeuvre to enjoy it. Writing for The New Yorker when the film first hit cineplexes, Pauline Kael said: "Mean Streets is a true original of our period, a triumph of personal filmmaking."

The Hurt Locker (2008)

Described as "ferociously suspenseful" by The New York Times and "a near-perfect movie" by Time magazine, it's no exaggeration to say that Kathryn Bigelow's "The Hurt Locker" is one of the best war movies of all time. It follows an Explosive Ordnance Disposal team during the second year of the Iraq War. Jeremy Renner's Sergeant First Class William James takes charge of the team after Staff Sergeant Matthew Thompson (Guy Pearce) is killed by an Iraqi insurgent. The tension builds exponentially during the film's 131 minute runtime, with the team disarming bombs and coming under sniper fire as they make their way through hostile terrain.

What sets "The Hurt Locker" apart from similarly-themed movies made during this period is that it tows the line between Hollywood thriller and gritty Iraq War exploration perfectly, refusing to shy away from the lead character's motives while still being endlessly entertaining. "Bigelow's film combines an expert management of tension with a sensitive and journalistic attention to detail: she has one eye on the truth and the other on the multiplex," said Time Out, while The Telegraph called it a "super-sharp, nerve-shredding thriller that reveals more about the realities of contemporary military conflict than most documentaries."

Zero Dark Thirty (2012)

Another near-perfect war thriller from Kathryn Bigelow, 2012's "Zero Dark Thirty" is a dramatization of the hunt for Osama bin Laden, the man behind the September 11 terrorist attacks. Jessica Chastain stars as a CIA intelligence analyst named Maya, who is in charge of the manhunt for the Al-Qaeda leader. The film spans the decade between the attacks and Operation Neptune Spear, in which a SEAL Team Six task force shot and killed bin Laden after raiding his compound in Pakistan.

This film came with its fair share of controversy, mainly for the way it depicts torture as a necessary evil. "Zero Dark Thirty" also contains some historical inaccuracies and factual errors. There's no getting around these failures on the part of the filmmakers, though when judging "Zero Dark Thirty" purely as a cinematic experience, it's absolutely riveting. The term "thrill ride" is overused in reviews, but rarely has it been more apt. As Entertainment Weekly's Owen Gleiberman said: "Once in a long while, a fresh-from-the-headlines movie fuses journalism, procedural high drama, and the oxygenated atmosphere of a thriller into a new version of history written with lightning."

Parasite (2019)

Bong Joon Ho's "Parasite" made history in 2020 when it became the first non-English language film to win the Oscar for best picture, with the South Korean filmmaker also scooping the award for best director. This dark comedy thriller follows the Kims, a poor family whose members gradually ingratiate themselves with the wealthy Park family, infiltrating their home and their lives in the process. It begins when Kim Ki-woo (Choi Woo-shik) gets a job teaching Park Da-hye (Jung Hyeon-jun) English using a forged certificate. Ki-woo goes on to secure jobs in the household for the other members of his family by lying about their experience, with the Kims keeping the fact that they're all related a secret from the Parks.

Parasite has a score of 97 on Metacritic and it also boasts a near-perfect rating on Rotten Tomatoes, where it's Certified Fresh with a rating of 99%. The general consensus among critics is that Bong Joon Ho's thrilling movie is nothing short of a masterpiece, one that stays with you long after the credits have rolled. "A film that always has two thoughts in its head at once, a spectacular epic and tightly wound chamber piece, chicly sophisticated, brutal as a hammer," said the Financial Times, while Empire magazine called it "a miracle of a film." One thing's for sure — "Parasite" is film that has plenty of rewatch value.

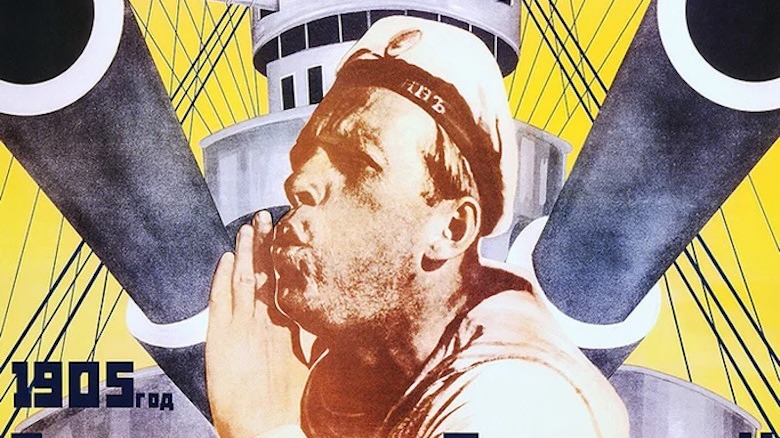

Battleship Potemkin (1925)

"Battleship Potemkin" is one of the first thrillers ever made. A silent movie designed to be accompanied by music, "Potemkin" was directed by Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein and boasts an intriguingly dual-natured origin. It's a government propaganda film, commissioned specifically to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the 1905 Russian Revolution and the actual Potemkin uprising, a key event on the road to the 1917 Russian Revolution. "Potemkin" also clarified and ultimately embodied Eisenstein's trailblazing theories of montage and film editing.

On both fronts, it was an unqualified success: Eisenstein's editing techniques create intense tension through juxtaposition, and laid the bedrock for the future of cinema. The end result is such an effective call for revolution that it was banned in several countries, for fear that the audience would be compelled to take up arms after watching it. In particular, the legendary "Odessa Steps" sequence is one of the single most influential montages in film history, and has been referenced in everything from "The Godfather" to "Revenge of the Sith."

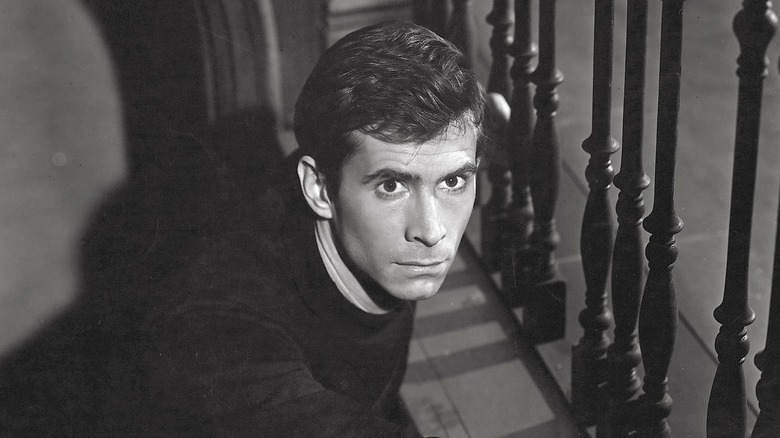

Psycho (1960)

In 1960, Alfred Hitchcock introduced the world to serial killer Norman Bates, one of cinema's best-known antagonists. By telling his twisted story, Hitchcock directly challenged the censorship practices of the era with the film's vivid depictions of violence and sexuality. "Psycho" is considered by many to be the first slasher movie, its success providing the foundation for an entirely new-sub genre that would go on to sweep the industry. "Psycho" also established Hitchcock as a master of horror — a genre closely related to, and often overlapping with thrillers — though almost none of his previous work could be classified as horror.

There are many elements that speak to the genius of "Psycho," but perhaps none is greater than the central bait-and-switch of its narrative arc. Hitchcock spends the early parts of the movie getting the audience firmly on the side of Janet Leigh's Marion Crane, a young woman who skips town after stealing from her boss. Crane is obviously the film's protagonist, which makes it utterly shocking when she's murdered halfway through the movie in the notorious shower scene. Said scene is one of film's most famous: 2017 saw the release of "78/52," an entire documentary about Hitchcock's shower scene.

Rififi (1955)

The genre that thrillers tend to overlap with most frequently is crime. Jules Dassin's "Rififi," a French film noir that the American Dassin made after becoming a victim of the infamous Hollywood blacklist, is one of the original heist movies. It is most notable for a 28-minute scene in which the four criminal protagonists chisel through a ceiling and drill into a safe, all in the absence of either music or dialogue. The total lack of any sound other than what's made by the thieves' tools in this scene invests it with a natural suspense. This renders the audience, in the words of Roger Ebert, "conspicuously hushed in sympathy."

Almost more interesting is the fact that "Rififi" is an adaptation of a novel by Auguste Le Breton that Dassin absolutely hated. Tasked with adapting a book he detested, he decided to expand the novel's brief heist scene into that now-legendary silent sequence that takes up a quarter of the film's running time. This allowed Dassin to simply ignore large portions of the original story — and end up in the annals of film history.

The Third Man (1949)

This list is populated largely by auteurs and filmmakers who exercise almost total creative control over their work. In contrast, Carol Reed's "The Third Man," which is considered one of the greatest British movies of all time, is very much a collaboration. It was produced by the legendary David O. Selznick and boasts a screenplay by the celebrated English novelist Graham Greene. It also benefits from a brilliant score by Austrian composer Anton Karas, which heavily features the zither.

However, it is Reed's implacable creative vision that drives the film. Unconventional angles and lighting uniquely capture the shattered streets of Vienna, the perfect backdrop for a story about an American author who gets sucked into Europe's seedy underbelly in the wake of World War II. The cherry on top is Orson Welles, who provides a historic performance as Harry Lime, one of cinema's greatest villains. He is presumed dead for most of the film before he makes his iconic entrance and delivers his unforgettable "cuckoo clock" speech.

North by Northwest (1959)

Alfred Hitchcock is well-represented on this list, but 1959's "North by Northwest" is unlike many of his other films, and serves a different function in history. It's still very much a thriller, and recognizably Hitchcockian in that it sends its protagonist staggering through a tangled web of crime, intrigue, and mistaken identity. But in its overall tone, it resembles an early action movie. It's been noted that "North by Northwest" can be considered an antecedent to the modern idea of the summer blockbuster. It specifically paved the way for the James Bond films – so much so that its star, Cary Grant, was originally approached to play Bond in 1962's "Dr. No" (he turned it down).

"North By Northwest" has a stronger commitment to keeping things light and funny than many Hitchcock movies. While Hitchcock's distinct sense of menace can be clearly felt, particularly in the scene where Grant's character is attacked by a crop duster, it's the moments of pure spectacle, like the climactic chase atop Mount Rushmore, that tend to be better remembered.

The Lady Vanishes (1938)

The earliest Hitchcock movie on this list, "The Lady Vanishes" is one of the most historically important entries in the Master of Suspense's filmography. Incorporating numerous elements which would eventually become seen as Hitchcockian, it specifically foreshadows "North by Northwest" as a spy thriller with strong comedic sensibilities that takes place, at least in part, on a moving train. It's also part of a legacy of films that feature a lone protagonist surrounded by people who mysteriously fail to remember events or characters the protagonist knows to have been real: The crowning achievement of this trend is 1944's "Gaslight," which spawned the term "gaslighting."

Most importantly, the commercial success of "The Lady Vanishes" launched Hitchcock's American career, as it caught the attention of David O. Selznick. Selznick subsequently drew Hitchcock across the Atlantic to make "Rebecca," a crucial step in his becoming the filmmaker we remember today.

Touch of Evil (1958)

Of all the movies on this list, "Touch of Evil" is perhaps the most surprising. Back in 1958, it was a critical and commercial failure, regarded as a mess of a film noir with a baffling plot that couldn't be saved by director (and co-star) Orson Welles' fancy cinematography. The film critics and audiences saw, however, was not the film Welles had intended them to see. Universal-International heavily re-edited the movie prior to its release, to the extent that Welles felt the need to write a 58-page memo explaining what his version would have looked like. Welles was already notorious for fighting with studios over creative control, and "Touch of Evil" proved to be the last straw — it was the last film he directed in Hollywood.

Fortunately, critical regard for "Touch of Evil" grew in the decades that followed, and in 1998, the film was re-edited based on Welles' memo. Today, it's seen as an undisputed classic, a movie defined by its unparalleled visual flair, encapsulated most memorably in the three minute opening scene that unfolds via a single heart-pounding camera shot.

The Night of the Hunter (1955)

"The Night of the Hunter," the directorial debut of Charles Laughton, is another thriller that went unappreciated when it first arrived — so much so that Laughton, who is much better known as an actor, never directed a film again. Looking back on it now, however, it's easy to see why it was eventually so influential.

The beating heart of "The Night of the Hunter" is Robert Mitchum, famed for his work portraying villains and antiheroes. His ghoulish Reverend Harry Powell is a singularly terrifying figure: He's a man whose religious delusions lead him to murder and deceit, yet whose charisma holds everyone he meets in the palms of his hands (which, for the first time in film history, are tattooed with the words "love" and "hate" across the knuckles). His pursuit of the movie's young protagonists is a legendary piece of suspense filmmaking that has inspired countless imitators and still holds up today. Laughton engages in some interesting (if muddled) themes involving sexuality and religion, but Mitchum's personification of evil is the main attraction.

Notorious (1946)

"Notorious" lives up to its name, broadly considered to be a major turning point in Hitchcock's career. Like "North by Northwest," it's a spy thriller starring Cary Grant, and it shares the same James Bond-like DNA of romantic political intrigue. But "Notorious" reaches uniquely spectacular heights, weaving a tale of a post-World War II love triangle between two spies on opposite sides (Grant and Claude Rains) and the double agent they both love (Ingrid Bergman).

Going over every cinematic innovation and scene in "Notorious" that went on to influence generations of future filmmakers would take far too long — and that's a compliment. Beyond those achievements, however, the winning essence of "Notorious" lies in the alchemy between the performers, Hitchcock's groundbreaking direction, and a script by Ben Hecht that flawlessly builds the relationships between the three main characters and their relationship to espionage itself. It also has one of cinema's best endings, with a final, brutally suspenseful sequence that concludes with the greatest possible payoff.

Vertigo (1958)

Every 10 years since 1952, Sight and Sound, a magazine published by the British Film Institute, conducts a poll of the world's leading film critics to determine the 10 greatest movies ever made. The magazine's second poll in 1962 crowned Orson Welles' "Citizen Kane" as the best film of all time, and it held that position for 50 years. In 2012, however, a new king of cinema was crowned: "Vertigo," Alfred Hitchcock's 1958 masterpiece, his final collaboration with star Jimmy Stewart, and the absolute pinnacle of his work in the themes of mistaken identity and the relationship between love and death.

Spoiling this film for anyone who hasn't seen it should be a criminal offense, so we won't. Suffice it to say that, like most of Hitchcock's films, it's a murder mystery, but the murder in question is incidental, a device that keeps the plot in place. The real mysteries being explored in "Vertigo" are those of its characters' psyches, as their various traumas, deceptions, and obsessions feed into a shifting, dream-like narrative where nothing is as it seems and the final antagonist is the mind itself.

Rear Window (1954)

This Hitchcock movie is another unusual murder mystery. Here, the mystery has nothing to do with the identity of the murderer — there's only ever one suspect. Rather, the mystery of "Rear Window" involves whether or not the murder took place at all, and if it did, can it be proven? Even then, that mystery isn't the thing that makes "Rear Window" one of the greatest thrillers ever. Its suspense comes from the fact that the main character, Jimmy Stewart's adventurous photographer L. B. Jefferies, spends the entire movie in a wheelchair with a broken leg, piecing the clues together while voyeuristically spying on his neighbors and sending his caretaker and girlfriend out to do the dirty work.

Movies often ask you to identify with the protagonist. Few movies, however, have the brazen audacity to literally place the protagonist in the audience's position of helpless observer, watching events unfold through a camera lens while unable to change what happens. In this, it's both a commentary on and a celebration of the movies themselves — and the ultimate suspense thriller. And if you were left confused by the ending of "Rear Window," here's a detailed explainer breaking it all down.