Movies That People Still Don't Understand

It's Saturday. You've gathered your friends around the television. The popcorn's on the table, and the beverages have been distributed. Everything should be ready for a great evening, right? Well, there are just four little words that can ruin any movie night. You know the ones: "I don't get it." Have you ever shown your friends a movie only to hear that response as the credits roll?

When you think about some of the mind-bending (or simply mind-numbing) movies you might find on Netflix, Hulu, or Amazon, it's actually not that it's surprising. People have widely divergent tastes, after all. But a lot of films are too heady and high-concept, or too confusing and clumsily made, and the only natural response is a resounding "huh?" Let's go over some of the more divisive pictures you may have watched on any given weekend, and pat ourselves on the back for the ones we know inside and out. Or, well, at least the ones we think we know.

Anyway, beware! Spoilers ahead!

Arrival

This 2016 first-contact feature offers a twist on the alien invasion premise by focusing the plot on last-ditch efforts to communicate with an alien race across an utterly imposing language barrier. It's a slower, more low-key movie, much of the the runtime given over to Amy Adam's expert linguist as she makes progress with the interstellar visitors. Throughout, the narrative is interspersed with flashes of her character in another life, caring for a daughter doomed to die young of disease.

While the natural inclination is to presume that these are flashbacks, it turns out we're witnessing a tragedy that hasn't happened yet. We learn at the film's climax—along with Adams' character—that the aliens are unbound by the laws of time, and their bond allows her to see into the future. For some viewers, the twist threw an extra wrench into the end of a plot that some audiences felt had already established its own rules. The movie, while among the year's most critically acclaimed wide releases, earned a B Cinemascore, suggesting a decent number of people walked away somewhat confused. Well, there's always Men in Black.

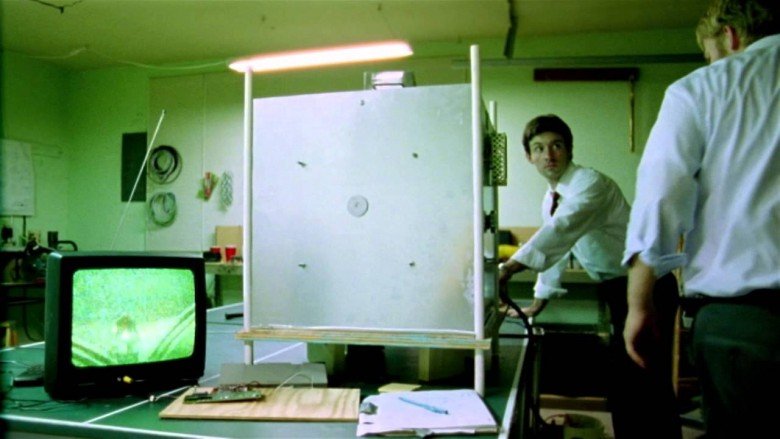

Primer

First-time filmmaker Shane Carruth's microbudget time-travel feature is a mindbending accomplishment, with Carruth writing, directing, editing, composing, acting as one of the leads, and having his nice parents cater the production. The story goes that Carruth, a software engineer, taught himself how to make a movie in the lead-up to production, and put a good deal of work into getting the math right to make the mechanics of his time travel as theoretically sound as possible.

The result is an uncompromisingly intellectual feature in which the two leads talk naturalistically far over the audience's heads, making the film a puzzle to be solved as much as a viewing experience. And it's a good movie, focusing on two smart but otherwise pretty regular guys getting very much over their heads very quickly as they break and create new timelines, the consequences of their invention spinning rapidly out of their control. You don't have to "get it" to enjoy it—but trying to keep up is definitely part of the appeal.

Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice

Oh boy. This movie isn't confusing because it's too smart for the audience—it's just doesn't make any sense.

From Wonder Woman's motivations to the basic structure of the plot—the who-does-what-and-why of it—BvS is a movie that barely hangs together, stitched up by sound and spectacle. The much-maligned Martha moment wasn't just a "head-scratching" failure because it was weird, but because it wasn't enough to explain why Bruce Wayne would suddenly decide to not fulfill a mission he'd pursued obsessively, justifying killing Superman by citing one-percent doctrine in between Crossfit sessions. Why, if it's an "absolute certainty" that Superman is a danger to the world, is simply hearing he also has a mom named Martha enough to make Batman, in the very next scenes, describe himself as Superman's "friend"? This, coupled with the movie's confusing dream sequences and visitations from a time-travelling Flash—a character we never actually meet—makes the movie feel fundamentally illogical, incomplete, and frustrating—especially if you're a fan of the characters who really wants to care about the story.

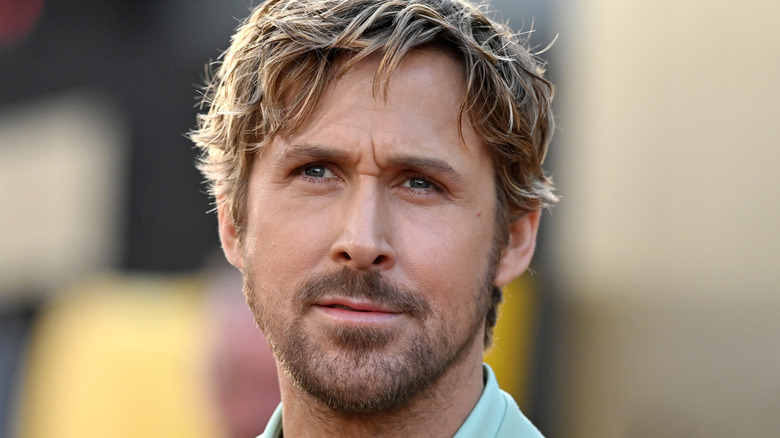

Only God Forgives

Nicolas Winding Refn and Ryan Gosling followed up their dreamy and fantastic Drive with a hard left turn into the abstract. Taking the action to Thailand, Ryan Gosling stars as, essentially, a 100 percent less interesting, not-driving version of his Drive character, wandering through the dreamy Bangkok cityscape like a modern-day ronin for reasons we're mostly left to guess.

In between, we're treated to surreal karaoke sequences from a character called both Lieutenant Chang and the Angel of Death, and described by the director as "a mythological creature that has a mysterious past but cannot relate to reality because he's heightened and he's pure fetish." The entire movie is like that. It's one of those films you can watch over and over again and never understand—it's either too impenetrable, or perhaps there's really nothing there.

Inland Empire

Of course a list like this is going to need some representation from David Lynch, the ur-king of surrealistic American cinema from Eraserhead on down. Mulholland Drive is a commonly cited misunderstood masterpiece, but at this point, everyone who cares has pretty much figured it out—the movie being, once you figure out the key, a pretty straightforward narrative.

Inland Empire, Lynch's 2006 follow-up (and his last feature film up to this point) is a completely different, bugnuts insane sort of beast. A three-hour, languid nightmare of a movie featuring Hollywood, street prostitutes, showbiz curses about "brutal f—ing murder" and a menacing situation comedy about rabbits, it makes Mulholland Drive look as easy to follow as an episode of Friends. It's also as close as Lynch has ever come to making a full-on horror movie, providing scares more startling and perplexing than he's ever dared before. To say it's not for everybody would be an understatement.

Bug

This claustrophobia-inducing 2006 psychological horror film from William Friedkin, director of The Exorcist, is one of the only movies in the 50-plus-year history of the organization to earn an "F" Cinemascore. And it's not hard to figure out why—this picture is weird, and abrasive, and makes you feel like you yourself might be going insane. Starring Ashley Judd and Michael Shannon and a script based off a play by Tracy Letts, this metaphorically methed-out feature about two people slowly going insane in an increasingly-tinfoil-wallpapered hotel room proved just too manic and ridiculous for audiences looking for something a little more substantial than two characters caught in a feedback loop of their own insane delusions. If you know what you're getting into, though, what you get is pretty good.

Prometheus

Sometimes it feels like we're always talking about this movie's puzzling failures, but there are plenty of good reasons. It has one of the most obtusely vague shooting scripts of any blockbuster in recent memory. Occupying an ambiguous "prequel" status in the Alien film canon, Prometheus confused audiences with everything from its casting choices to its characters' basic motivations to its very denouement.

It didn't have to be that way, but the whole experience gives off an impression of "almost... almost," hints at plot and story without the necessary parts that make an audience care. We personally witnessed many viewers literally throwing their hands up in the air by the time the movie's wrapping up, unable to connect to anything happening. It's so weird and fundamentally unsatisfying, it's no surprise the franchise is eager to get distance, forgoing Prometheus 2 and calling the followup Alien: Covenant instead. Maybe they'll get it right this time.

The Butterfly Effect

Serious actor Ashton Kutcher's The Butterfly Effect is one of the dumbest movies ever to remain essentially watchable while being completely illogical, with a plot that falls apart if you think about it even for a second. Kutcher's protagonist, blessed (or perhaps... cursed) with the ability to use old personal tokens to phase back through time to memorable moments in his life, spends the bulk of the movie trying to fix his mistakes, usually only to emerge in situations that are even worse.

The premise of the movie, that the slightest change can change the course of your life entirely, gets betrayed consistently when the script needs it, breaking its own rules without explanation. In one scene, as Kutcher tries to defend himself inside a violent prison, he goes back in time to stab his hands and mimic stigmata, frightening the other inmates with his sudden new hand wounds. But if going back in time to change the slightest thing changes everything, then why is Kutcher's present still in jail? Why did the wounds appear as if by magic, instead of appearing scarred over after what should have been an entire life of having them? Is it really worth it to try and figure out this movie's logic, as it would be with the vastly superior Primer? Well... no. So if you don't get this one, don't worry. No one does. It's broken.

The Prestige

Christopher Nolan's dueling magicians movie is slight-of-hand in cinematic form, a mystery that keeps all its clues in plain sight. In retrospect, it's blindingly obvious that Christian Bale is playing two separate characters throughout the film, but as the movie itself posits, it works as a twist because "you want to be fooled." Still, there's one aspect of the movie—the ending—that has continued to leave viewers confused.

Using Tesla's technology to upstage his rival Borden, Hugh Jackman's Angier cloned himself night after night, dropping one duplicate into a water tank to drown while his other duplicate teleported elsewhere in the theater to rousing applause, only ever leaving one alive. But who is the real consciousness, and the real Angier? As Tesla says regarding a field full of Angier's cloned headwear, "They are all your hats." All of the Angiers are the "real" Angier, exact copies who share the exact same memories, motivations, and a fear of death.

The ending shows the length Angier will go to for his magic, as he wheels a covered box into a secret warehouse after a performance, revealing an entire macabre storeroom of his own dead, duplicated bodies, literal skeletons in his closet that demonstrate the corrosion of his soul. Over and over again, he dies for applause, always leaving behind a living version of himself, a copy of a copy increasingly haunted by the knowledge that soon it will be his turn to drown screaming in a box.

Cloud Atlas

The Wachowskis have boundless imagination, and no movie distills their achingly sincere humanism into a narrative like the epic Cloud Atlas, which intertwines six unrelated stories.

Many have tried to connect these stories logically, deciphering the ways they nest in one another. Some of the stories are portrayed as literary fiction in another world, yet characters within these stories are somehow often suggested to be reincarnated versions of each other. So what's the "real world" of this movie? How do these connections work?

Simply put, it's not supposed to make logical sense—it's supposed to make emotional sense. It's by design that some of the characters nest in fictional stories, casting doubt on what takes place in the "real world," because this is a story about stories. It's no coincidence that the movie begins and ends with the framing story of an elderly Zachary telling a tale around a fire. Don't worry about who's reborn as who or why. All of these recurring actors and recurring themes are meant to add up one meaning: in fiction, and in life, everything, and everyone is connected, a beautiful, massive, fundamentally unknowable tapestry that stretches further than any one person could ever grasp. It's a story—six stories—that adds up to a tale of universal humanity.

Trance

This Danny Boyle picture didn't make a huge impression on moviegoers when it came out, with a twisty heist plot one reviewer noted as "purposely convoluted" and "impossible to keep up with." It doesn't help that the movie plays fast and loose with the bounds of reality, particularly with the concept of therapeutic hypnosis—a real thing that the film portrays as something closer to sorcery than science.

Trance isn't interested in giving viewers a chance to outsmart it; it doles information out slowly between dream sequences that serve to further confuse. The movie's secret is that despite the deliberately confusing structure, the plot is straightforward.

Elizabeth, the therapist played by Rosario Dawson, was behind the art heist central to the movie. Prior to this, she was also in an ill-fated relationship with Simon, played by James McAvoy. In using hypnosis to make Simon forget their relationship, she also implanted the idea of an art heist in his mind. During the attempt to recall Simon's memories, Elizabeth forms a brief relationship with McAvoy's criminal boss Franck—but he ends up as manipulated as everyone else. Throughout it all, she keeps her motivations mostly to herself, emerging at the end as an ice cold, unbelievably smart puppetmaster who was willing to let a lot of people die to get her hands on some money (and revenge).

Upstream Color

While Shane Carruth's second movie is just as complex as his previous work, the legendarily complex Primer, it's a different type of head-scratcher. Where the confusing aspects of Primer concerned hard science and heady theory, Upstream Color's plot is meant to function with emotional logic being the key to understanding its abstract themes—human connectivity, how it works, how it develops, how it frays, and what it means. This connectivity is represented by a parasitic organism (naturally) which infects hosts and tunes them into a continuous shared consciousness, drawing them together inexplicably with no surface logic.

This is the movie's cycle: the parasite, used by a thief, infects Kris, putting her in a suggestible state that leads her to destroy her life. Drawn to a pig farmer who uses music to attract the parasite, Kris has the parasite removed. It's then implanted in the pigs, whose offspring are thrown in the river to die. Their decomposing bodies, filled with the parasite, infect orchids by the river, which the Thief sifts through, searching for larva that contain the parasite, and the process begins again. Kris and Jeff, another former host, interrupt this process by becoming increasingly aware of the psychic links that bind all victims of the organism together, eventually killing the farmer. In the end, they invite all the other victims to the farm and a community is born in trauma, the cycle broken.

Under the Skin

This Scotland-set, largely silent alien abduction movie is unlike any other in the sci-fi genre. It's truly only an abduction movie for the first half—after which the alien, played by Scarlett Johansson, becomes disillusioned with luring humans into traps and destroying their bodies for unknown ends. When one potential victim's pure innocence jolts her into letting him go free, the alien goes rogue, curious about this planet, its people, and her role as an alien in disguise.

The second half of the movie follows the alien trying to grapple with a growing sense of her own humanity, and the vulnerability that comes with it. Her journey is cut short during an isolated walk, attacked by a rapist who, upon discovering her otherworldly true identity, is repulsed. Seeing not a human but a monster, the attacker chases down and burns the alien alive. Look past the sci-fi aspects, and this is essentially the story of a young woman's self-discovery—and her devastating, fatal realization that the human world is harsh, unfair, and full of horrors.

Possession

One of the most bonkers, crazy, like-nothing-you've-ever-seen horror movies ever made, Possession is a fever dream of a narrative held together by two outstandingly dedicated performances from lead actors Sam Neill and Isabelle Adjani. Everything, including the setting of Cold War-era divided Berlin, should be interpreted through the context of a catastrophically painful divorce. They destroy each other, they destroy themselves. Their lives unraveling from self-inflicted damage, they spend the entire film either just shy of or fully in the throes of a pitched mania. Many reviewers, especially at the time, took this intentionally heightened form of performance as bad acting, but the truth is exactly the opposite—Adjani and Neill deliver committed performances to maintain a tone.

Beyond confusion about the story in general, the ending is also a bit of a head trip. As it turns out, there is a monster in this movie, a horrible creature that eventually evolves into an idealized doppelgänger of Sam Neill's character. Examined as an aspect of divorce, the monster is a living manifestation of jealousy and infidelity, the representation of all Neill's character can no longer be to his wife. Taken as a straight-up creature feature, the movie reads as nonsense. It's only in the subtext that it starts to make "sense." But regardless of whether you can get on board, it's hard not to agree about one thing: there will never be a dramatic depiction of a miscarriage as abstract, horrifying, and maddeningly violent as this one.

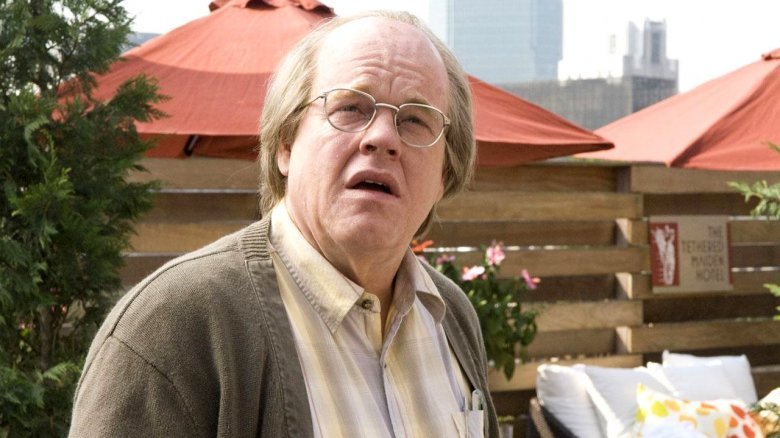

Synecdoche, New York

Upon unexpectedly receiving a MacArthur Genius Grant, a frustrated play producer sets out to create a work of art with true resonance, hoping to attain a meaning in his life that has long eluded him through art. Does he succeed? Well... we all die, so does anyone really succeed at anything? Think about it, man. Whoa.

Joking aside, it's no exaggeration to say that Synecdoche, New York is a movie about everything and everyone. As Roger Ebert noted in his laudatory review, it's a story about "you, whoever you are." The sprawling, ever-changing cast, which features different actors playing the same characters in the production over the course of decades, speaks to the essence of identity—how we're seen and perceived as we perform our roles in life, with our small successes, painful failures, and major flaws. Caden Cotard, played by Philip Seymour Hoffman, is an artist obsessed with creating the perfect artwork—and accomplishing the goal is just as impossible as living a perfect life. No one can do it, and we will all die trying.

The key to understanding works by Charlie Kaufman, the scribe behind cinematic mind-benders such as Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Being John Malkovich, is that there's no distinction between the dream world and reality. Everything is real, existing together in a surrealistic stew, and the impossible aspects of the movie represent real feelings. Very little in the film is literal—but everything feels true.

Demon

This highly-regarded Polish horror picture is the best portrayal of a wedding ceremony falling apart since Melancholia. The story follows an English groom as he arrives in his fiancée's native Poland for a grand wedding before her gathered family. After an encounter in the yard with a buried skeleton, the protagonist's emotional state—and his sanity—starts to fray. He's haunted by visions, possessed by a dead woman who wants to live and love again, her takeover of his body culminating in his utter breakdown as the family presses on with the ceremony, trying to distract from the horror by getting everybody drunk as the whole affair falls into chaos.

Near the end, one family member mentions that the husband is gone—and indeed, he never appears again, and the movie ends quietly soon after. But what does this mean? Did he vanish of his own accord? Was he taken by the demon? Or did the wife's family do him in to be rid of him? There are no answers in this anticlimax. The family's response, though, is clear: raze over the wedding site. Forget this ever happened. Put his truck in a lake and pretend he was never here. It's a metaphor for postwar wounds and the distrust sowed by nationalism: you can bury the past all you want, but the message of the movie, in a number of ways, is that your history will always find a way to resurface.

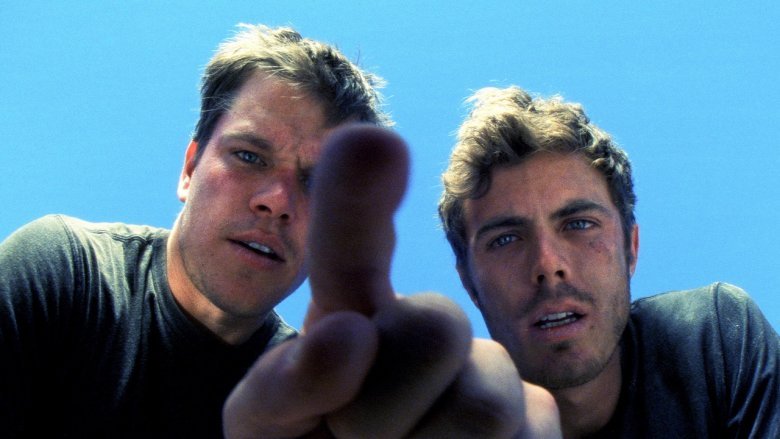

Gerry

Gerry, a movie about nothing that's led untold numbers of moviegoers to shut the film off midway through while cursing its name, is the first in director Gus Van Sant's "Death Trilogy," a triptych of meditative films that analyze very different, very intense ways people have met their ends.

Two characters, both named Gerry, are on a hike, looking for "the thing" before becoming hopelessly lost. They navigate the endless landscape, always striving ahead toward... something. Their relationship frays. They make mistakes and blame each other and themselves for being chronic screwups. "You Gerried it," they tell each other, their own names and very natures synonymous with bumbling failure.

Out of all this nothingness, a parable emerges about every human's clumsy journey through the world, adamantly marching on with steely determination in an unknowable expanse toward the vaguest goals. As an experimental movie, it's an ink blot; the two protagonists could be anyone, their conflicts could be anything, and their journey could be to anywhere. In this way, Gerry becomes a universal story, serving as a mirror for viewers, reflecting the petty conflicts, the inane challenges, the damage we do to each other and ourselves—and finally, yes, the overwhelming boredom of life.

Filth

Filth follows James McAvoy as corrupt cop Bruce Robertson, a no-good guy whose life is off the rails and getting worse. While the film was marketed as a bad behavior comedy—and for awhile, it pretty much is—it steadily veers off course to become a portrait of psychological torment. The tonal shift is so dramatic, and its details so bizarre, that it's no surprise viewers can end up losing the plot amidst the spectacle, particularly during the last-act reveal that Bruce has been spending his nights roaming the streets dressed as his own estranged wife. Starting as a murder mystery involving a missing student, it's revealed at the end that Bruce was never going to be able to solve the murder, at least not on his terms. The truth is, while on one of his cross-dressed jaunts, he witnessed the murder—a fact he can't reveal without incriminating himself.

Hiding his corruption from the world is the substance of what he calls "the games"—games of one-upsmanship and subterfuge that we all play in life to get the best of each other while revealing nothing negative about ourselves. This is what he means by his catchphrase "same rules apply"—that is, the rules of these games apply to us all. So in the final moments of the film, even though Robertson has a shot at redemption, he chooses the approach that reveals the least about his inner torment, and hangs himself—the ultimate kiss-off from a selfish, self-preserving mistanthrope.

Solaris

In Solaris, a space station hovers over a mysterious ocean planet, which despite decades of research has remained unknowable to its observers. Worse, the only data scientists on Earth have received from the station has been borderline nonsensical, and eyewitness reports of impossible beings on the planet's surface from people who've been there are dismissed as hallucinations. A psychologist from Earth makes the journey to Solaris to examine the state of the crew, and decide if observations should continue. But upon arrival, he too begins to experience impossible phenomena: phantoms flicker in his vision; his long-dead wife appears to him, miraculously revived. Though the psychologist knows she can't be real, and must be a vision produced by Solaris, the manifestation becomes as compelling as the real thing.

Solaris' ending, in which the psychologist appears to be back on Earth after his mission—only for it to be revealed that his perfect patch of Earth is an island adrift in Solaris' endless sea—has long fascinated viewers with its ambiguity. In deciding whether or not to remain above Solaris or return home, it appears that the psychologist has chosen to fall into Solaris and replicate his ideal Earth. But why? The reason is offered by one of the scientists on the station, who's spent years above the planet. Speaking on behalf of humanity, he says we have no desire to "conquer any cosmos." "We don't need other worlds," he says. "We need a mirror."

Eraserhead

David Lynch's moody, surrealistic first feature is far simpler to comprehend than its reputation has come to suggest, even if its dreamlike imagery isn't always meant to literally "mean" something. At its core, this is a story about the incomparable terror of being a new parent. In the first scene, which sees protagonist Henry floating in space above a distinctly ovum-shaped moon, Henry bellows out a sperm-shaped object, which appears to then, well, you know.

Henry and his wife Mary give birth to a monstrously deformed creature, and their relationship frays. He seeks an escape—finding solace in, of all places, his apartment radiator, where a small, kind-hearted singer lives. (Look, you're either on board or you're not.) However you wish to interpret the striking imagery Lynch employs, most close readings of the film should land in the same ballpark. More than evoking anxieties of parenthood, or being a parable for dissatisfaction, it evokes a fear universal to all people—of making decisions of great consequence, and being unable to turn back from them. It plays on our doubts and our need to escape, and if you read it differently than someone else, that's not a bad thing. Lynch himself has said the movie is open to interpretation, and that "no one, to my knowledge, has ever seen the film the way I see it." Which is exactly the point. Sometimes with movies, it's not about plot logic. It's all about how it makes you feel.