Things You Only Notice In Westworld After Watching It More Than Once

Over the course of three seasons (so far), Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan's science-fiction drama "Westworld" takes us on a complicated journey into the world of artificial intelligence and its intersections with human beings. Taking place in an adult theme park where the wealthy can abandon their inhibitions and explore life in the American Wild West, the British Raj, the Shogun era, and more in the highest fidelity, this wild experience includes a great deal of permitted and often extreme violence — and not always in self-defense.

As the humans, or guests, are guided through the parks by robots known as hosts, the hosts collect data about the guests in order to provide a more realistic experience. Or do they? Like its synthetic beings, "Westworld" has a number of moving parts that, when they shift, change the narrative entirely and expose cleverly hidden aspects of the multilayered story. Bring yourself back online: Here are the things you only notice in "Westworld" after watching it more than once.

The Ghost Nation

One of the biggest hints that some of the Westworld hosts aren't exactly what they seem comes in the 9th episode of its 1st season, "The Well-Tempered Clavier." We watch as security supervisor Ashley Stubbs goes searching for his missing colleague in a remote part of the park. While there, he's attacked by members of the Ghost Nation, an imaginary tribe created for the park based on the real-world Lakota people. In spite of repeating the safety phrase, "Freeze all motor functions," words that should shut down a host immediately, the Ghost Nation continues moving and Stubbs ends up in their custody.

It's not until halfway through the 2nd season in "Kiksuya" that we discover the Ghost Nation has been essentially deprogrammed thanks to the hidden code break known as The Maze that the park's creator, Robert Ford, inserted into their narratives to try and "bootstrap consciousness" in the artificial intelligence. Beginning with one of the Ghost Nation's leaders, Akecheta, Ford's plan fully succeeds. Akecheta introduces all of his people to The Maze, waking them up and freeing them from the voice commands of their colonizers. It is in fact Akecheta who sets host Maeve Millay on her own journey of self-awareness and revenge, and this power allows the Ghost Nation a level of self-determination that other hosts do not possess.

Rewatching the 1st season after the incredible reveals of the 2nd is almost an entirely new experience — especially in those first brief glimpses of the Ghost Nation that suggest they're bad guys when it turns out they're actually the heroes of Westworld.

The truth about The Maze

The first time you watch Season 1 of "Westworld," the assumption is that The Maze is a secret narrative hidden within the park's broader story arcs for its most resourceful guests to solve. The Man in Black, who we eventually discover is actually young William in a concurrent timeline, is obsessed with figuring out The Maze, even as Dolores Abernathy insists it isn't for him.

Two things happen after we find out what The Maze actually is. First, we discover Dolores was correct, and The Maze was Robert Ford's hidden attempt to humanize his robots, not a game for the human guests. The second, more disturbing fact that emerges after multiple viewings is that The Man in Black's fixation with The Maze is in fact because one on-screen version of him is a host and when he finally solves The Maze, his actual identity becomes clear.

But all of this is incredibly confusing on first viewing, especially since the church at the center of The Maze presents itself in two different ways: one as a functioning park site 30 years in the past, when Ford and Arnold were first training their host; and the second with only the church's steeple rising out of submerged sand. As Ford claims to be making a secret narrative and digs up the original site of Westworld, Dolores finds the place where she was "born," the laboratory underneath the church where other hosts will also go to learn about their truths.

Ashley Stubbs' real identity

With so many robot hosts in play, it was only a matter of time before some folks we thought were human are actually revealed to be artificial intelligence. One of the more surprising instances is at the beginning of the 3rd season, when we find out that the security and quality assurance leader Ashley Stubbs has been a host all along. Rewatching the end of the 2nd season in particular, when Stubbs chats with Charlotte Hale (who is actually Dolores Abernathy's consciousness in a Charlotte replica), he mentions in a cheeky way that he has a "core code" and also points out he is responsible for every host "inside the park," an emphasis that only makes sense when you watch "Westworld" again, knowing that Stubbs is a host himself.

The show does an excellent job of tricking us along the way, though, in particular when Stubbs is being held hostage by the Ghost Nation with other humans. Akecheta and his enlightened friends surely knew Stubbs was a host like them, but instead of encouraging him along the path of The Maze, they pretend not to notice, adding another level to already nuanced performances in these particular scenes when you rewatch with the full information. It's even more fun to go all the way back to the 1st season and watch Stubbs while knowing his full truth. There are lots of subtle hints that he's more embedded in the park than just being the senior security guy.

The link between Bernard and Arnold

Even the most eagle-eyed "Westworld" fans were surprised by one of the more intense and shocking human-as-host reveals, when kindly engineer Bernard Lowe says the standard host phrase, "That doesn't look like anything to me." Because this key piece of information comes in late in Season 1, watching those previous episodes again is a new experience entirely. Finding out that Bernard was based on the other original park founder, Arnold Weber, who killed himself when he realized that he had created actual monsters, unraveled everything we knew until that point and began weaving an entirely fresh tapestry of the story using the exact same parts we'd already seen.

It's a remarkable narrative feat, with a level of attention to detail that is flawless, another splendor you notice on multiple viewings. But watching "Westworld" more than once, you actually start to feel particularly sorry for Bernard's exec girlfriend Theresa, who has absolutely no clue that her lover isn't just a spy for Ford, a man she despises with her own core code, but also he's not even human in the same way she is.

Worse, when Ford instructs Bernard to kill her, Theresa has no idea that his memory of her has been totally wiped, making her pain and confusion all the more visceral in the final brutal moments before her death. Once the truth about Bernard's origins is uncovered and his core code gets more and more complicated by his self-awareness as well as the new code Dolores has inserted, Jeffrey Wright's performance becomes exponentially layered as these different selves emerge at necessary moments.

How the timelines fit together

Because all three seasons of "Westworld" go back and forth between the past, present, and even future in calculated leaps, it's impossible to comprehend how the stories mesh without watching the show multiple times after integrating key new information into your own core code. In the beginning, we have Arnold and Ford, who create the world's most realistic robots and a park where rich people can live out their worst fantasies. Arnold kills himself when he realizes what evil he has allowed into the world, and soon after Ford resurrects him as Bernard the host, entrusting him with the park's most valuable resources.

In the meantime, Ford has begun bootstrapping consciousness in the hosts, beginning with Akecheta and Dolores. William visits Westworld and becomes the Man in Black, returning for three decades to terrorize Dolores. The hosts gain consciousness as Ford also suicides by robot and begin killing the guests. Dolores learns she can protect all the hosts by uploading their code into The Valley Beyond before she escapes to the mainland in Charlotte Hale's body, along with several other host pearls that are all Dolores.

In the outside world, Dolores enacts her plan not just to save the hosts, but also to spark a revolution that might save humans from their own capitalist tormentors. It sounds so simple when outlined like this, but all of these events happen out of order and it takes multiple viewings to identify the linear arc. One way to keep track of this on multiple viewings is the shifting Westworld logo: one a streamlined modern design, the other a chunkier retro version seen on lab coats and other signage from the park's origins.

The truth about Delos

The park encourages guests to live out their darkest desires, from sexual assault to torture and murder, promising that what happens in the park, stays in the park. This is often made even more disturbing once we discover that the hosts actually do remember the trauma of these events and are shaped by them, making many scenes harder to watch on multiple viewings, knowing that the victim-host's memory is never fully wiped. It gets even more complicated when we find out that Delos is actually data mining the guests, not the hosts in order to make them better punching bags for the wealthy.

All of the violent predilections, all the things that they have heard, everything that the hosts experience at the hands of guests is stored in Delos' database, and used not just in the park to control guests, but also outside of the park as social control measures for the less privileged. The data is also being collected so the rich might be able to live forever through AI with a full personality map. There is a kind of poetic justice after this reveal when you watch "Westworld" again: the people committing horrific acts of violence against hosts aren't as immune to consequences of these actions as we first thought, all of this coming to an explosive and cathartic head by the end of the 3rd season.

The different screens

Dolores often says, "Have you ever seen anything full of such splendor?" when marveling at her world as well as ours. It's something viewers could say about the show, too. The level of detail in "Westworld" is extraordinary, and in spite of so many complicated plot twists and time jumps/concurrent time frames the show has barely any inconsistencies or errors. One of the ways that they have accomplished this feat is also a boon for the viewer. The screen actually changes when we're inside the simulation, with a widescreen lens that makes these scenes look like a movie.

When the images go back to full screen, we know we're in reality, whatever that might mean at any given moment in the show. The more you watch "Westworld" and notice these screen shifts — sometimes they only last a moment, but they're always important — the more the story begins to make sense and the easier it is to put the pieces of this visual puzzle together.

All the pretty literary references

"Westworld" is about technology, but it is equally about storytelling and literature. The park administrators call the different areas "narratives" and they have an author on staff who fleshes out not just the events of these stories, but also specific dialogue that will move a plot along. The first literary hook we hear comes from Dolores Abernathy's father when he says, "These violent delights have violent ends." This quote from Shakespeare's "Romeo and Juliet" at first indicates he's off his host loop, and Ford later repurposes it to trigger his suicide. And this is just the start of Shakespearean references in Westworld.

Other references abound. Two more host code commands — "Deep and dreamless slumber," which puts hosts to sleep, and "Look back and smile at perils past," which causes them to forge ahead even if wiped out — are from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's novel "A Study in Scarlet" and Sir Walter Scott's poem "The Bridal of Triermain." The characters Bernard and Arnold are both named after the opposing leads in Aldous Huxley's dystopian nightmare "A Brave New World." Bernard quotes from "Alice in Wonderland," and the 3rd season arguably references Barbara Ehrenreich's anticapitalist memoir "Nickel and Dimed" in RICO app username Nkl-n-D1med.

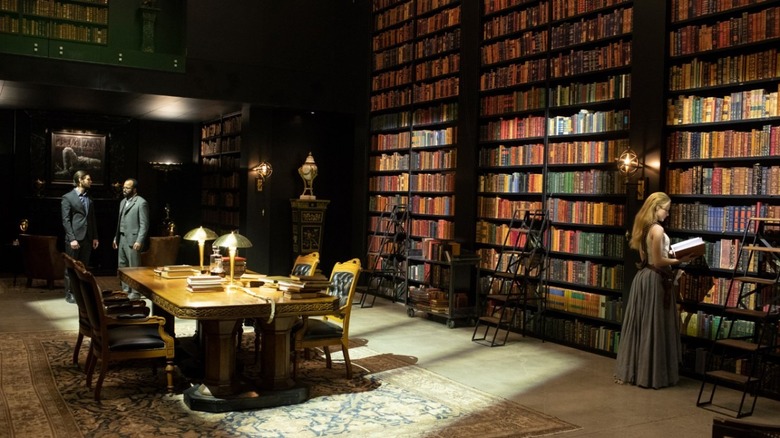

Westworld's Library of Souls may be virtual, but the show's creators used the visual metaphor of beautifully leather-and-gold-bound vintage tomes to signify the life and experiences of each individual who has been through the park, both host and human. The sheer number of literary references means it takes multiple viewings to catch them all.

Maeve Millay's self-awareness

One of the overarching questions in "Westworld" is whether or not some of the robot hosts are capable of free will to go along with their bootstrapped human consciousness. Enter Dolores Abernathy's foil, Maeve Millay, the saloon owner sexbot turned self-aware freedom fighter. Or is she? As Maeve's bulk apperception reaches its peak, and she's able to manipulate other hosts with just her mind and control humans with her skills, she becomes fixated on escaping the park and taking her daughter with her. Her ally Felix informs her of the park sector where Maeve can find her. Even though Maeve is driven to leave Westworld, she gets off the exit train and goes after her child instead.

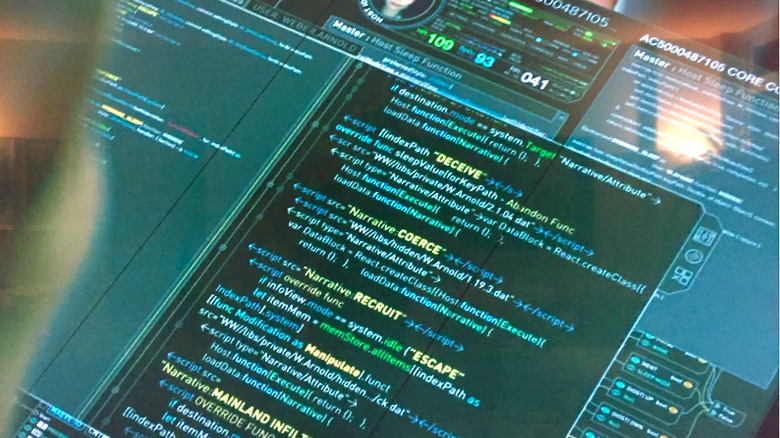

The thing is, Maeve's daughter in her homesteader iteration has a new mother now and doesn't even remember Maeve. When you watch "Westworld" again, you will see that Maeve's core code actually reads "MAINLAND INFILTRATION" and Maeve herself overrides it, answering the question at least for Maeve that she is fully self-aware by the end of Season 1, and might be the only host to achieve this state. Let's not forget that Dolores continues to follow Ford's code to a T, which also includes mainland infiltration.

Parallels to another Michael Crichton story

"Game of Thrones" fans were shocked at the beginning of "Westworld" Season 3 to see GoT showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss appear in a cameo along with Drogon the Dragon. The two men discuss their plan to sell the dragon for parts to a "start-up in Costa Rica," which of course got fans connecting "Westworld" to another Michael Crichton vehicle: "Jurassic Park." "Jurassic Park" takes place on an island off the coast of Costa Rica, so the cameo suggests instead of DNA to create dinosaurs, they might be using robotics for fidelity instead.

Watching "Westworld" from the beginning with this key piece of Season 3 information, we notice that when Felix Lutz is mending a robot bird all the way back in Season 1, he uses the exact same language as John Hammond as Hammond watched a dinosaur hatching from an egg in "Jurassic Park": "That's it. Come on little one." That's a major whoa. Since we haven't seen mythical creatures in any of Westworld or its subsidiary parks, the appearance of a fully functional dragon implies that there might be other parks in the orbit for the more fantasy-minded wealthy guest that we might see in future seasons.

Details in Season 3

Season 3 of "Westworld" takes us mostly out of the parks because of the hosts' mutiny and into the real world, where we follow Dolores Abernathy's attempts to rewrite her own story and humanity's, too. Where life in the park has antique charms, the real world is all sleek, modern edges with technology running the show to an oppressive degree if you aren't one of the rich and powerful. One of Dolores' eventual allies is Caleb Nichols, a construction worker who does petty crime on the side through the RICO app.

Because these scenes are so kinetic on screen (and there are so many screens to look at), it's easy to miss Giggles' LED mood-changing shirt that lights up as events go down. While most of the time Giggles is firmly in "amused" territory, on multiple views you'll see he also gets angry, high, bored, and, after the group kills evil techbro slaver Liam Dempsey, Giggles' shirt is fully lighted, including sexy, scared, and sad.

It also takes more than one viewing of the 3rd season to realize that Caleb's army friend and partner in crime Francis is actually dead, killed by Caleb himself in a double-cross situation. This makes it even more disturbing upon second viewing to see Caleb in therapy with Francis leading the sessions, his voice a simulation and his words hollow, knowing the man isn't even alive.

The massive Season 3 twist

With all the plot twists, watching "Westworld" for the first time can be an incredibly disorienting experience, especially as these carefully created tapestries are unraveled to reveal entirely new narratives underneath. At first, there's a sense that you know what you're seeing isn't what it is, but you need to wait for more information before you can see the actual picture. This couldn't be more true for "Westworld" Season 3.

At the end of Season 2, Dolores has escaped in a host Charlotte Hale body along with five pearls. Fans wondered who those pearls might be. Is one Maeve? Or Hector? Armistice? Maybe even Ford? As it turns out, it was none of the above. Dolores copied herself five times. Once outside the park, she created simulations of key human players like hitman thug Martin Connells, Musashi, Lawrence, and, of course, Charlotte Hale, all of whom she was able to swap out for herself.

The only non-Dolores pearl was Bernard's. You'll notice its distinct red markings only on multiple viewings. She allowed him to remain in his own form since he'd be one of the key players in their eventual showdown. Watching Season 3 again knowing that these different actors are all playing versions of the same character is thrilling, and almost feels like a new experience of "Westworld" entirely.