Is Gangs Of New York Based On A True Story?

It's a cliche these days, but they simply don't make movies like "Gangs of New York" anymore. Martin Scorsese's sprawling 2002 drama is an epic of revenge, fathers and sons, and violent, bloody wars between New York immigrants for the right to live — and die — in America.

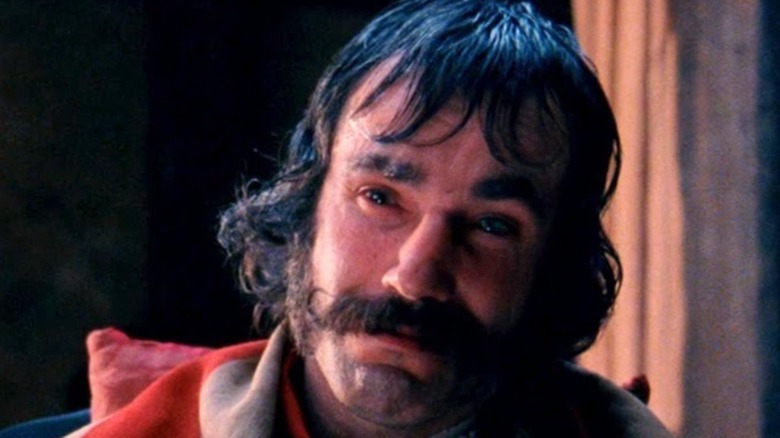

Set in 1863, the film stars Leonardo DiCaprio as Amsterdam Vallon, an Irish Catholic who sets upon a plan of revenge against Bill the Butcher (Daniel Day-Lewis). Bill, a bigoted Protestant nativist, slew Amsterdam's father (Liam Neeson) in a gang battle and has ruled the Five Points slums of Manhattan ever since. Soon, their conflict encompasses Jenny (Cameron Diaz), a pickpocket and Bill's former ward, all of the gangs of the Five Points, and eventually, in the shocking climax, the infamous 1863 Draft Riots.

Scorsese and his crew went to special lengths in order to recreate 19th-century New York, including the construction of a massive set, according to author Fergus M. Bordewich. But how much of the film is fictional, and how much happened in real life? This is the reality of "Gangs of New York."

Gangs of New York has some real-world inspiration

While the film's events are largely fictional, save for the Draft Riots, much of the script was inspired directly by the extremely entertaining nonfiction book "The Gangs of New York," published in 1927 by journalist Herbert Asbury. Scorsese had read the book in the '70s and tried to get a film made out of the material for decades until he finally succeeded, per author Fergus M. Bordewich.

So while Amsterdam Vallon and the 1846 gang war that opens the movie were written for the screen, gangs like the Dead Rabbits, the Plug Uglies, and the Bowery Boys were very real and often fought each other to control territory and settle inter-gang disputes. The Dead Rabbits carried at the head of their sluggers a dead rabbit impaled on a pike, with this symbol becoming a major plot point within the film. They also found common cause with other gangs — and even rivals — to fight against the Bowery Boys, with whom they had a bitter feud, as noted by All That's Interesting.

Hell-Cat Maggie and Bill The Butcher are truer to life than expected

This mix of fiction and reality animates much of the film's approach to adapting history, with several film characters having real parallels. For instance, Hell-Cat Maggie, memorably shown in the movie attacking gang members with sharp nails and teeth, seems too outlandish to exist outside of imagination, but she also appears in Asbury's book as a known gang fighter; when Hell-Cat Maggie "rushed biting and clawing into the midst of a mass of opposing gangsters, even the most stout hearted blanched and fled," as quoted by How Stuff Works.

Boss Tweed (Jim Broadbent), meanwhile, was an infamously corrupt politician in American history whose Tammany Hall machine effectively controlled New York for decades, even if his tensions with Bill the Butcher were written for the screen (via Britannica).

Bill is based loosely on William Poole, a nativist and Bowery Boy member. Poole was also nicknamed Bill the Butcher for his professional trade, and like Day-Lewis' character, could throw "a butcher knife through an inch of pine at twenty feet, according to City of Smoke. Unlike his film counterpart, however, Poole still had both eyes, and in fact, History Daily wrote that he enjoyed gouging out his opponent's eyes during bare-knuckle boxing matches.

Poole died several years before the Draft Riots, though his demise was similarly plotted by Irish immigrant John Morrissey in an act of revenge, and he was cornered and shot by Dead Rabbit members. He lingered for several days but his wounds were too much even for him. Still, Murder by Gaslight noted that his dying words were nearly the same as Bill's last line in the movie: "Good bye, boys: I die a true American!"

The Draft Riots were horrifically real

The Draft Riots at the heart of the movie's climax, which disrupted, then finished Amsterdam and Bill's feud once and for all, were also a real event that was described vividly and at length in Asbury's book.

Led by white working-class New Yorkers, the riots took place over several days and, similar to what is depicted in the film, were motivated by resentment over the wealthy buying their way out of the draft, as well as bigotry and fear of free African Americans who were looking for work. The protests soon turned into a race riot, with many Black people being targeted, according to History. Unlike the film, the Navy never fired on New York citizens, but by the time the military did restore order after several days, mobs had destroyed numerous buildings, which included the burning of a Black orphanage, and more than a hundred citizens had died.

The film correctly surmises that the city had once again irrevocably changed in the wake of the Riots: "But for those of us what lived and died in them furious days, it was like everything we knew was mildly swept away."

If you'd like to see the "blood and tribulation" of Scorsese's 19th century New York for yourself, "Gangs of New York" is streaming on Hulu.