The Untold Truth Of Steven Spielberg

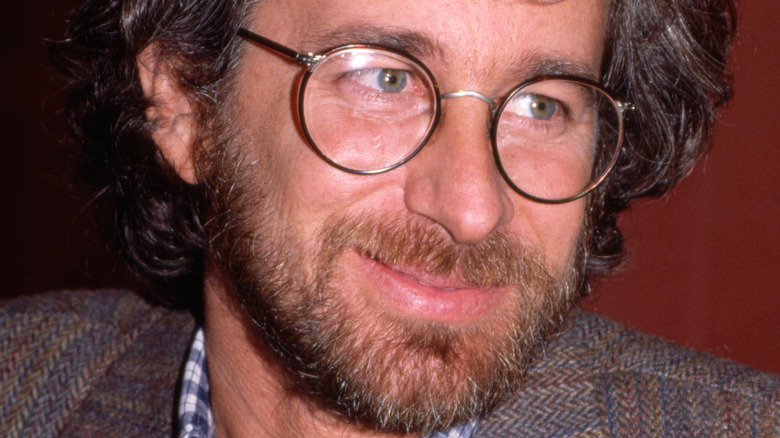

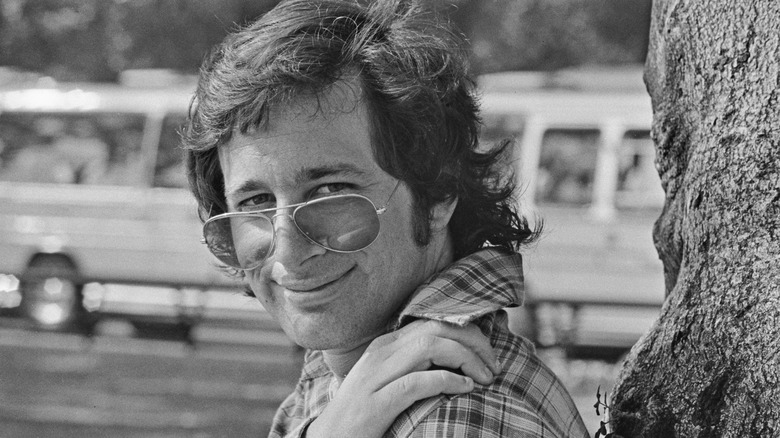

If you ask 10 people to name a great director, odds are at least one — if not all of them — is going to say "Steven Spielberg." For over half a century now, he's towered above his peers in success, talent, and versatility. He's proven he can do white-knuckle action better than anybody with blockbuster classics like "Jaws" and "Raiders of the Lost Ark." But he can also do heavy historical epics like "Schindler's List" and "Saving Private Ryan," heart-tugging family dramas like "E.T.," thought-provoking sci-fi like "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," and everything in between.

He's kept a demanding schedule for all that time, often releasing multiple films in a year, but even that's not the extent of his contributions. First with Amblin and then with Dreamworks, he's also been one of Hollywood's biggest producers, shepherding other directors' visions to the screens with some of the biggest hits and best classics of our lifetime. Not bad for a kid from the Cincinnati suburbs. But how did he get from there to where he is now? As you might imagine, it's a long journey full of fascinating stories. Here are just a couple of them.

Spielberg's mom helped his career in an amazing way

We all remember being little kids and telling adults what we want to be when we grow up. Very few of us ever stay on the path we chose in our grade-school days, but little Stevie Spielberg knew he was going to be a director ever since age 8, when he got his first camera and went to work in the deserts outside his home in Phoenix, Arizona. According to Joseph McBride's "Steven Spielberg: A Biography," as a teenager, his backyard war epic "Escape to Nowhere" got the attention of the local news station, and he screened his first feature-length film, "Firelight" — made for the princely sum of $600 — at the Phoenix Little Theater.

Most parents would try to make sure their kids' hobbies don't get in the way of schoolwork. But Spielberg's mother, Leah, wasn't most parents. In a 1992 interview on "60 Minutes," she says she actively helped little Spielberg play hooky so he'd have more time to hone his skills. As she explained, "I used to lie, I wrote marvelous notes. I'm very creative; I could always think up a new ailment to keep my kid home from school!"

He tells some colorful stories about how he got started

Spielberg is very much an old-school director, modeling himself on the great Golden Age directors like John Ford and Cecil B. DeMille, and he has their same talent for hype. Look no further than the origin story Richard Schickel quotes in "Steven Spielberg: A Retrospective." One day, teenaged Spielberg was on a tour of Universal Studios, and when the guide let the group stop for a bathroom break, the future director never came back. He "had an amazing time" wandering the studio unsupervised, but there was still the matter of how to get home. Fortunately, he found Universal archivist Chuck Silvers, who was so impressed with the daring young fan he wrote him a three-day pass. When it ran out, Spielberg continued hanging around just like he belonged, which was good enough to convince the actual employees that he did.

It's a great story, but Spielberg may not have let facts get in its way. Biographer Joseph McBride has produced documents suggesting Spielberg met Silvers through much more official channels. But some of Spielberg's stories from that time don't need any embellishing. An editor asked Spielberg to pick up a film viewer, getting him yelled at by a huge, half-naked man who turned out to be Marlon Brando. In college, he'd sleep in a Universal office in his clothes but kept a pressed suit on hand so he could walk out in the morning looking like a professional. And Charlton Heston says he snuck in and got thrown off his set so many times that the director finally let him stay.

John Cassavettes introduced Spielberg to a whole different side of filmmaking

If you want to understand how Spielberg was able to rise through the Hollywood ranks so quickly, look no further than his unparalleled shmoozing skills. According to biographer Joseph McBride, he'd walk right up to stars like Rock Hudson and Cary Grant and invite them to lunch. The eager young film fan was so ingratiating that some big-time movers and shakers actually sought him out. "Rosemary's Baby" star John Cassavettes asked Spielberg what he wanted to do in Hollywood, and when he learned the young man was a director, he encouraged Spielberg to give him directions right then and there.

Cassavettes was an accomplished director himself, practically inventing the American independent movie with microbudget films like "A Woman Under the Influence" and "Faces," a literal "home movie" he filmed at his own house and invited Spielberg to work as a production assistant on. While most of Spielberg's peers would follow in Cassavettes' footsteps, he would go in the opposite direction, reviving the big-budget crowd-pleasing spectacles Cassavettes defined himself against. But the older director was still a major influence. Spielberg says watching how affectionately Cassavettes treated his cast was the best lesson he ever got.

He launched his career by launching two TV classics

Spielberg's wheeling and dealing landed him his first studio directing job when he was only 22. And what a job — he would direct the legendary Old Hollywood star Joan Crawford in the first episode of Rod Serling's "Twilight Zone" follow-up, "Night Gallery." A story from Joseph McBride's book shows how much faith the studio had in Spielberg. Crawford got the job because her "Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?" co-star, Bette Davis, refused to work with such a young director — and instead of replacing him, the studio replaced her!

Crawford was much more accommodating. When she learned this was Spielberg's first commercial film, she invited him to dinner and told him, "You'll want your first work as a director to be something you can be proud of, and I'll break my a** to help you. ... If you have any problems with [the studio], let me take care of it."

Spielberg also had a hand in kickstarting one of the era's defining series, "Columbo," following up the two standalone movies with the first official episode of its eight-year run. That episode, "Murder by the Book," is immediately recognizable as a Spielberg joint right from the first scene, a dizzying shot that floats from a parked car to an office several stories above. He obviously made a big impression on the writers — they'd name child prodigy Stevie Spielberg in a later episode after the "boy genius" director.

Spielberg had to re-edit Duel for a hilarious reason

Spielberg had a lot of success in his early TV career, but none of his hits were as big, or as enduring, as "Duel." This ABC Movie of the Week adapted a short story from "Incredible Shrinking Man" author Richard Matheson — one about a traveling salesman stalked across the desert by a homicidal truck and its never-seen driver. According to Richard Schickel in "Steven Spielberg: A Retrospective," the director turned the story into an unforgettably tense classic on a tight 11-day shooting schedule by plotting the shoot on a hand-drawn map of the highway, complete with marks for camera placement.

"Duel" was popular enough to get a second run in European theaters, and Spielberg recalled making a discovery twice as terrifying as anything that happens to his hapless salesman. The wide theater screen revealed details that the boxy TV format of the time cut off. That included Spielberg himself, who was visible in, by his estimate, 17 shots, directing star Dennis Weaver from the backseat. The movie had to go back to the editing room to cut him out again.

Spielberg chickened out on making 1941 a musical

After "Jaws" tore up box office records as thoroughly as its killer shark tore up all those poor swimmers, Spielberg got free rein to do whatever he wanted. That freedom paid off with another hit in the alien drama "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," but his luck ran out on his next project, "1941." Spielberg had tons of expensive effects, and he tapped an all-star cast of hip, young comics including John Candy, John Belushi, and Dan Aykroyd, but the film was in trouble from the first screening.

In the opening scene, a self-parody of "Jaws" with the submarine in the place of the shark, the audience was absolutely loving it. "We thought we had something very special," producer John Veitch explained to Empire. However, as the film went on, that laughter "started to dissipate."

The ambitious, expensive movie bombed so hard it almost killed Spielberg's career just as it began. So maybe it's for the best he didn't go as ambitious and expensive as he originally considered. According to historian Joseph McBride, Spielberg said, "In the back of my mind, I always saw '1941' as an old-fashioned Hollywood musical. ...I just didn't have the courage at that time in my life to tackle a musical." Maybe that's for the best — he had a hard enough time tackling comedy, and if he'd taken an even bigger swing at a genre that was box office poison at the time, he may have never recovered.

He was the only Raiders crewmember to avoid food poisoning

Spielberg recovered from the failure of "1941" with one of the biggest successes of his career, "Raiders of the Lost Ark." It was almost as if he was determined to come back from his World War II-set flop by making one of the all-time great movies about the era. And for a capper, he'd go on to make the other two with "Schindler's List" and "Saving Private Ryan."

That doesn't mean "Raiders" didn't have its share of setbacks. This globetrotting adventure had a globetrotting production, including the North African country of Tunisia, standing in for Cairo, Egypt. That turned out to be a difficult locale for the shoot. Karen Allen, who starred as Marion Ravenwood, told Variety that while the crew dealt with water safety issues by buying bottles at $2 a pop, their sellers were actually just filling bottles up from the tap. That led to mass illness on the set, and the local food didn't exactly help either. However, Spielberg was spared. How? Well, as Allen remembers, "He had boxes of baked beans and Spaghetti-O's, and he was sort of living on that because it kept him healthy." It's possibly the only time that diet was good for anybody's health.

It wasn't all bad though. These difficult circumstances famously inspired one of the movie's most iconic scenes, when Harrison Ford wasn't up to an elaborate swordfight in the script and rewrote it to end the scene with a hilarious one-sided gun battle.

He helped kickstart the animation renaissance

Spielberg is a prolific director but an even more prolific producer, with almost 200 credits to his name. And even though he wouldn't direct an animated movie himself until motion-capture technology brought it more in line with his skillset for "The Adventures of Tintin," Spielberg did as much as anyone to shake the medium out of its decades-long doldrums. When TV began sucking up movie theaters' audiences, theater owners lost interest in the expensive shorts packages that had powered the animation industry up until then. Many animators moved onto TV, but the low budgets and demanding schedules forced them to do as little actual animation as possible. With profits down, this attitude even took hold at Disney.

One Disney animator, Don Bluth, was unsatisfied with their approach, so he jumped ship to make the much more elaborate "The Secret of NIMH." This got Spielberg's attention, and he put his weight behind Bluth's next two films, "An American Tail" and "The Land Before Time." And just as he did with live-action films, Spielberg brought animation into the future by looking to the past in "Who Framed Roger Rabbit." His protegé, Robert Zemeckis, revived dozens of classic cartoon characters, with animation director Richard Williams providing animation so spectacular it made those classics look downright cheap. Spielberg had so much fun with that, he did the same on TV, first with "Tiny Toon Adventures," then "Animaniacs" and "Freakazoid." Other studios saw how successful his approach was, and soon, animation regained some of its former glory.

An American Tail was very personal to Steven Spielberg

Spielberg often contributes a lot more than funding to his productions, and there are few better examples than "An American Tail." This cartoon classic retold the story of America's immigrant history with Fievel Mousekewitz, youngest son of a family of Jewish mice fleeing from anti-Semitic violence in Russia.

This story was very personal to Spielberg. His own family came to the States in similar circumstances, including his maternal grandfather, Fievel Posner. Biographer Joseph McBride even draws parallels between a scene of the animated Fievel sadly pressing his nose against a school window and a story from the real Fievel. Because of a law limiting the number of Jewish students, he would sit out in the snow and take his lessons through the window.

Spielberg had to fight to get this tribute to his grandfather on film. According to John Cawley's book "The Animated Films of Don Bluth," director Don Bluth complained "Fievel" was too "foreign" for audiences to embrace or even remember. Spielberg won out, and he proved Bluth wrong. Audiences remembered Fievel's name well enough to come back for one theatrical and two video sequels, as well as a TV series.

Another story from McBride makes it clear how important Grandpa Fievel was to Spielberg. A producer was so impressed by one of his early TV projects that he asked, "How the h*** do you know what pain is? In your young life, how do you know about pain?" Spielberg responded, "Every week I used to go visit my grandfather in the nursing home."

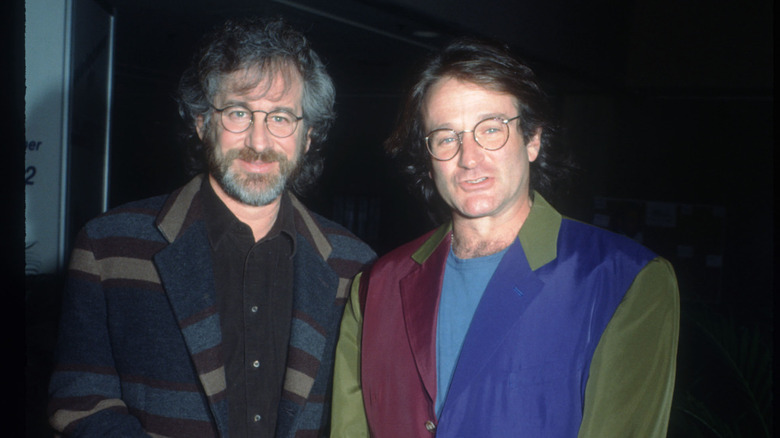

Robin Williams helped Spielberg through Schindler's List

Spielberg spent much of his life grappling with his Jewish heritage, especially since he grew up among Holocaust survivors. He has one especially vivid memory of a man who tried to entertain him as a toddler with a "magic trick" involving his concentration camp tattoo, turning a six into a nine by flexing his arm.

In 1982, his producer, Sid Sheinberg, bought Spielberg the rights to Thomas Keneally's novel "Schindler's Ark." In a DGA interview, Spielberg said, "I didn't have the maturity, the craft, and the emotional information to be able to acquit the Holocaust ... without bringing shame to the memory of the survivors, and especially to those who didn't survive." So he spent the next decade trying to find someone else to take on the burden until he finally felt he could do it himself.

Still, it was incredibly hard for Spielberg, who was dealing with some pretty serious emotions during the shoot. However, he came to "Schindler's List" fresh off making "Hook" with Robin Williams, and they'd clearly made a connection because Williams knew just what Spielberg needed. At the 2018 Tribeca Film Festival, Spielberg said, "Robin knew what I was going through, and once a week, Robin would call me on schedule and he would do 15 minutes of stand-up on the phone. I would laugh hysterically because I had to release so much."

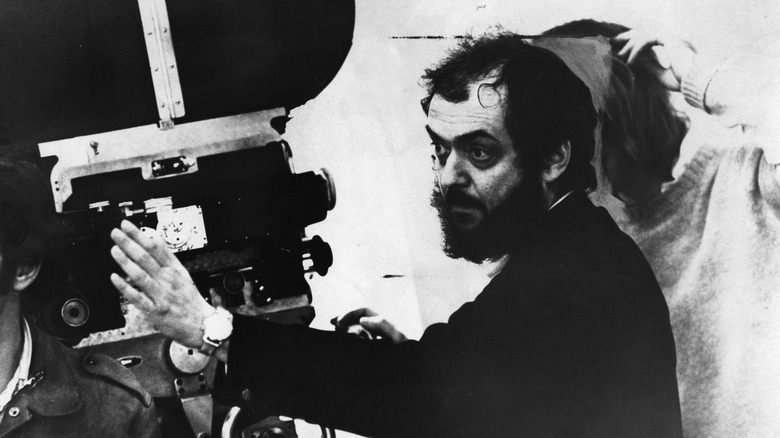

Spielberg's relationship with Stanley Kubrick

Spielberg's success was a dream come true for such an avid film fan. Not only did he get to meet many of his idols — some of them even idolized him. He built one of his longest and most profitable friendships with Stanley Kubrick. The older filmmaker was one of the true legends in the field, whose groundbreaking work included "Dr. Strangelove," "2001: A Space Odyssey," and "The Shining."

And there was his final film, left unfinished at his death but completed by Spielberg. "A.I.: Artificial Intelligence" is Kubrick's reimagining of the "Pinocchio" formula based on the science fiction story "Supertoys Last All Summer Long." According to biographer Richard Schickel, Kubrick originally planned to create his protagonist, David, entirely through special effects. When he came to realize that he'd need a real child, he was so busy with his final movie, "Eyes Wide Shut," that he knew a child actor would grow up before he finished working around his other schedule. Seeing similarities between "A.I." and Spielberg's work, he handed the story to his protegé.

Their collaboration was the fruit of a years-long relationship. They were so close that Spielberg and Kubrick faxed each other all the time. This turned out to be a much worse idea than it sounds. As Spielberg explained (via The Playlist), Kubrick took this form of communication very seriously. "Stanley said, 'Okay, get a fax machine with a dedicated line that nobody can read. ... You must have a secure room somewhere in your house. ... With telephones and steel walls." Kubrick went on to say, "Don't let anybody read what I write to you. And when I'm done writing, and you're done reading it, and you've memorized it, I want you to tear it up, or better yet, shred it."

Well, Spielberg ended up putting the fax machine in his bedroom, and the eccentric filmmaker faxed him both day and night.