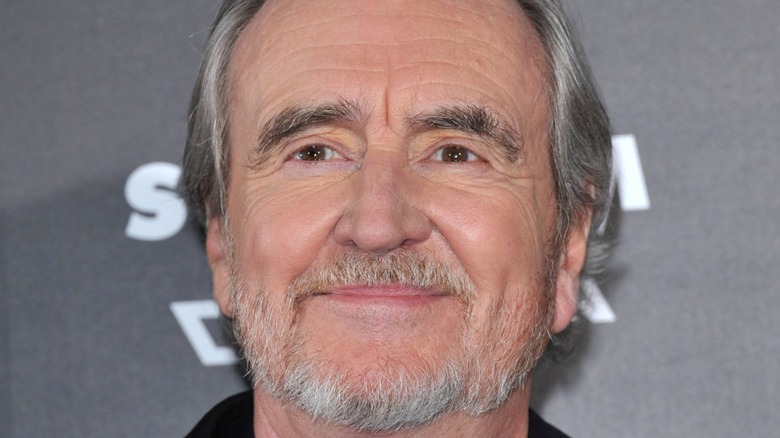

This Is Wes Craven's Biggest Regret About A Nightmare On Elm Street

The late Wes Craven was one of the greatest minds in the history of cinema. His creativity, even within the constraints of low-budget indie filmmaking, was boundless. The vision and savvy with which he approached scary stories is what made him famous — and deservedly so. Craven was one of those directors who knew exactly what he was doing, somehow always managing to stay one step ahead of the audience.

Case in point: "A Nightmare on Elm Street," his 1984 tale about a group of teens caught between dreams and reality. Freddy Krueger's chilling design, Robert Englund's singular performance, and the ghastly inventiveness of the nightmare set pieces all make the movie iconic. But the fact that the film remains an overwhelming horror experience decades later can be attributed, at its core, to one thing: Craven knew how to keep the line between truth and fiction blurry. "A Nightmare on Elm Street" plays with our inherited preconceptions about horror movies again and again, until there's no solid ground left underneath our feet. Of all the slasher classics, "A Nightmare on Elm Street" may be the most auteur-driven — and that's why it remains beloved.

Unsurprisingly, Craven's biggest regret about the final product stemmed from a sense of relinquished control over one specific scene. He expounded upon this in a 2014 oral history of "A Nightmare on Elm Street," which Vulture ran in celebration of the original film's 30th anniversary.

Wes Craven didn't want the movie to end on a sequel hook

Vulture's oral history was an opportunity for Craven to get candid about his feelings, including his distaste for the final scene of "A Nightmare on Elm Street." According to New Line Cinema founder Robert Shaye, the original script included "an ending where Heather vanquishes Freddy and goes off to school the next day. It's beautiful sunshine, and that's the end." This was in line with Craven's vision, which, in his words, had the film end with protagonist Nancy "[turning] her back on Freddy and his violence — that's the one thing that kills him."

But Shaye felt this ending lacked a "zinger:" "[Shaye] wanted a hook for a sequel," Craven detailed. "[He] wanted to have Freddy pick up the kids in a car and drive off, which reversed everything I was trying to say." Faced with such an impasse, the two men came up with a compromise: The film would end with the revelation that the kids' convertible has Freddie's red and green stripes, followed by an ambiguous finish. Neither man liked that ending much, but, as Shaye tells it, "We just left it the way it was."

"Do I regret changing the ending? I do," Craven expounded, "because it's the one part of the film that isn't me." Indeed, when the success of "A Nightmare on Elm Street" inevitably spawned a litany of sequels, Craven wasn't involved. It wasn't until 1994's "Wes Craven's New Nightmare" that he was brought back into the fold. In typical Cravenian fashion, "New Nightmare" is an inventive meta-play on the concept of the horror sequel.