Questionable Things We Ignore In The Harry Potter Franchise

There are a lot of franchises dotting the modern media landscape, but it terms of sheer impact, there's nothing quite like "Harry Potter." Since the first book's original publication in the United Kingdom in 1997 and subsequent journey across the pond in 1998, "Harry Potter" has both dominated and transformed Western media, becoming an unassailable monolith of pop culture. Today, it's the primary fictional touchstone of an entire generation: A 2011 survey found that a full third of Americans ages 18 to 34 had read at least one of the "Harry Potter" books. It single-handedly resuscitated the children's literature market, made geek culture mainstream, and spawned a full library's worth of imitators. There's a strong argument to be made that "Harry Potter" is the single most influential piece of media since "Star Wars."

This influence, however, can be complicated. The "Harry Potter" story contains a number of questionable elements we tend to skim over, or ignore entirely, due to the story's outsized place in our lives. We might find these eyebrow-raising details, themes, and plot devices strange, disconcerting, or even shocking in other franchises, but in "Harry Potter," we give them a pass. Today, however, we're looking those odd "Harry Potter" elements straight in the eye. By the time we're done examining them, even the staunchest "Potter" die-hards will have to agree: There are some real issues here.

Sorting is a horrible idea

The extent of the "Harry Potter" phenomenon can be summed up with a single question: "What's your Hogwarts house?" Most people below a certain age have either been asked this directly, or encountered it online at least once. For those within the "Harry Potter" fandom, the answer to this question is a source of personal identity. Every Hogwarts student is sorted, upon their arrival, into one of four houses: Gryffindor, Hufflepuff, Ravenclaw, or Slytherin. Where you end up depends on your personality traits. Gryffindors, for example, tend to be bold and daring, whereas Hufflepuffs are loyal and hard-working. Your house gives you a group identity within the school, and often determines who your friends will be — bonds that can last a lifetime in the close-knit wizarding world.

That's all well and good ... except that everyone's house is determined when they're 11 years old, and it never, ever changes. No amount of growth or transformation a student undergoes between the ages of 11 and 17 affects their house placement: Once you're sorted, you stay where you were put. House labels go on to follow people into their adult lives, through social connections, work placements, and stigma. We would prefer not to be eternally defined by who we were at the age of 11, personally. It's mightily messed up that kids in "Harry Potter" are branded with a specific personality type before even reaching adolescence.

Slytherin equals evil

When you tell children from age 11 on that they are defined by certain inherent elements of their personalities, you're going to create an entire school's worth of self-fulfilling prophecies. And while that might not be as much of a problem when you tell a kid they're inherently brave, smart, or diligent, it becomes a significantly bigger concern when you tell a kid they're inherently evil. That is essentially what Hogwarts tells every child sorted into Slytherin.

The list of Slytherin character traits has been dramatically stretched by the online sorting quiz industry, but within the text of "Harry Potter," they are presented as being fundamentally evil. The series' primary villain, Voldemort, is a Slytherin, as are secondary villains Dolores Umbridge and Severus Snape (we'll get to him later), and almost every Death Eater. The primary representative of supposedly non-evil Slytherins, Horace Slughorn, is a greedy, self-centered bigot. The Sorting Hat, which sings about the differences between the houses, describes Slytherins in one song as ambitious — the trait the quizzes have latched onto — but elsewhere says they "use any means to achieve their ends." For all Rowling's attempts to redeem the Slytherins, her story still ends with one of Harry's children being concerned that a magic hat might brand him as a conniving schemer for the rest of his life.

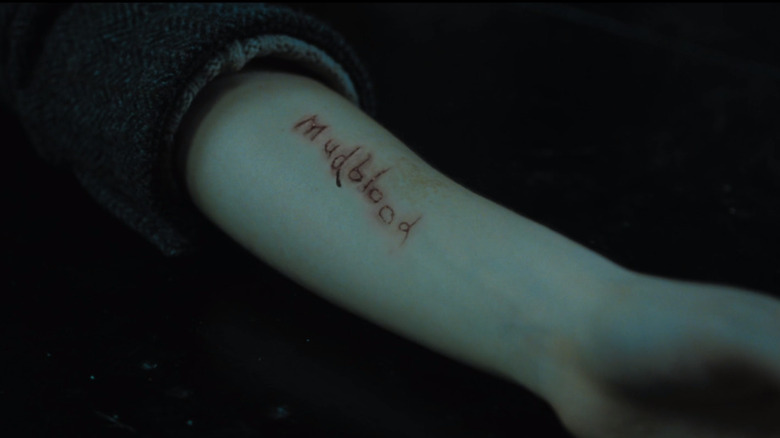

Discrimination comes in just one flavor

The biggest issue with Slytherin House is that Slytherins tend toward a distinct type of discrimination. Specifically, they hold bigoted views against Muggles (regular, non-magical humans) and Muggle-borns (wizards who were born to Muggle families, as opposed to wizarding families). This ancestry-based prejudice is used by Rowling to explore themes of bigotry, and she largely does a good job with it. Still, it's a little weird that the wizarding world contains no other kind of discrimination whatsoever.

Hogwarts students come in a variety of skin colors, but there's no indication of racial prejudice in the wizarding world. Nor does the wizarding world appear to discriminate on the basis of gender. As for religion, the wizarding world doesn't seem to have much in the way of religion at all, or at least nothing any of the main characters care about. While that might be explainable if the wizarding world were completely cut off from other humans, the existence of Muggle-borns makes that impossible. Some wizards grow up in Muggle families and, presumably, have the chance to learn various Muggle prejudices before they turn 11. Yet those prejudices never make it into "Harry Potter," not even the later, darker books, suggesting it's a subject Rowling simply had no interest in exploring.

The wizarding world has no problem with slavery

The scope of intra-human bigotry is flattened in "Harry Potter," but human bigotry towards non-human races thrives. For the most part, it's the series' villains who have the biggest problems with beings like centaurs and goblins. But in one particular instance, prejudice is a quality shared by the entire wizarding world. "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets" introduces us to house-elves, a species of magical beings bound to individual wizards as, essentially, slaves. Moreover, house-elves appear to enjoy and even psychologically depend on their own slavery.

Interestingly, the first house-elf we meet, Dobby, is a rare example of a house-elf who wants to be free. Harry does indeed free him, in one of the most triumphant moments in the series. However, in "Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire," we learn that house-elves also work in Hogwarts. Furthermore, we learn they can fall into deep depressions after being freed, and that pretty much everybody in the wizarding world is okay with this. The sole exceptions are Hermione Granger, whose activism for house-elf freedom is rooted in her experiences as a Muggle-born witch, and Albus Dumbledore, who offers Hogwarts' house-elves wages which they mostly do not take. Everyone else is apparently cool with this appalling situation.

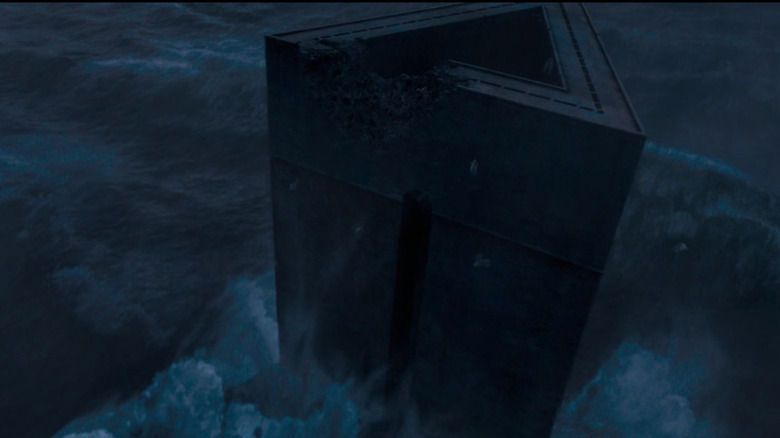

There's only one prison, and it's a nightmare

Azkaban is the wizarding world's prison, and what a prison it is. Azkaban isn't a place for rehabilitation — anyone who spends a significant amount of time there is probably going to go insane or die, thanks to its Dementor guards. Dementors are a race of dark, sadistic creatures which slowly suck out a person's happiness, will to live, and sometimes the soul itself. That's a pretty harsh punishment to condemn people to, even murderers and torturers.

Of course, murderers and torturers are by no means the only people imprisoned in Azkaban. Minor crimes, like trespassing, burglary, and owning dangerous animals can result in Azkaban sentences, and while they're usually on the shorter side, it doesn't take long for the prison to make an impression. Hagrid spends a mere two months in Azkaban and comes away haunted by the experience, while Marvolo Gaunt's six-month stint leaves him so severely weakened, he dies shortly afterward. There are no other magical prisons in Britain, which has been the case since Azkaban was built in the 15th century. That means the wizarding world has allowed these inhumane practices to continue for hundreds of years. They eventually do get rid of the Dementors, who sided with Voldemort, but we still wouldn't put much faith in the wizarding justice system.

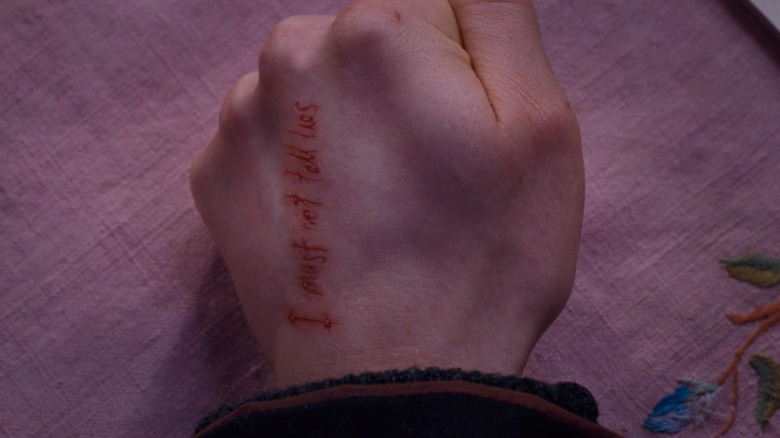

The kids work for the Ministry of Magic

There's really no good reason to trust the wizarding world's government. Beyond the fact that it sanctions house-elf slavery and locks up prisoners with a bunch of soul-sucking vampires, the Ministry of Magic is a constant thorn in the side of our heroes. Over the course of the series' seven books, they nearly always appear in a villainous capacity (or at least an annoyingly bureaucratic one). Perhaps the most vivid example is Dolores Umbridge, a Ministry official and the central villain of "Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix," who spends her time persecuting Harry and shutting down free thought. By "Deathly Hallows," the Ministry and the Death Eaters are functionally the same thing. Even before the Ministry is taken over by Voldemort, both Harry and Hermione have openly refused to work for them.

And yet, when the war is over and Voldemort is defeated, Harry and Hermione ... go and work for them. According to Rowling, they each become department heads in the Ministry, and "Harry Potter and the Cursed Child" reveals that Hermione eventually becomes Minister for Magic. Turns out everything is fine, as long as our heroes are in charge. We suppose Harry just wears gloves to work so nobody asks him about the "I must not tell lies" scar that Umbridge gave him during the Ministry's anti-Harry-Potter propaganda campaign.

The Weasleys aren't really poor

At least one actually decent person works for the Ministry of Magic: Arthur Weasley, patriarch of the Weasley family. The Weasleys are a big deal in the "Harry Potter" narrative — nearly every member of the family is a major character, a good deal of the non-Hogwarts action takes place at their house, and Harry himself eventually becomes a member of the clan. The Weasleys, however, aren't entirely what they seem. While the "Harry Potter" series insists over and over again that they are poor, the rest of the wizarding world would have to be staggeringly rich for that to be true.

The Weasleys own a house, first off. They have seven children, five of whom are still at home during the time of the series. Yet they seem perfectly capable of feeding and clothing all of them: When Harry and his friends go on the run in "Deathly Hallows," Ron is the one who is least able to handle the absence of regular meals, suggesting he's never missed one in his life. Bringing Harry into the family doesn't seem to be a financial strain — in fact, considering his inherited riches, he could be a boon to the Weasleys, if they weren't too proud to accept his help. The Weasleys' poverty manifests mainly in the fact that they're embarrassed to be poor, and if that's your biggest problem, you're not actually that poor.

Hogwarts is an awful school

It's possible that economics don't work the same way in the wizarding world as they do in the Muggle world, despite all the apparent similarities. There might be some kind of Ministry social program that keeps wizards above a certain baseline level of poverty. We sure hope so, because if the wizarding job market is anything like the real one, anybody with a Hogwarts education is getting absolutely screwed. There are seven required courses of study at Hogwarts: Astronomy, Charms, Defense Against the Dark Arts, Transfiguration, Herbology, History of Magic, and Potions. Other classes can be taken as electives, but those seven are the ones you need. To be considered a well-rounded witch or wizard, ready to take your place in adult society, these are the skills you must master.

But not, you know, math. Or English, or any form of science that doesn't involve incantation. Students attend Hogwarts from ages 11 to 17, and they presumably aren't taking classes somewhere else during that time. That means that the average Hogwarts graduate is less educated than the average American middle school student. Upon graduation, Hogwarts sends its students out to take their place in the secret society they all share, where magic is real and often shockingly dangerous. No wonder the wizarding world is such a mess.

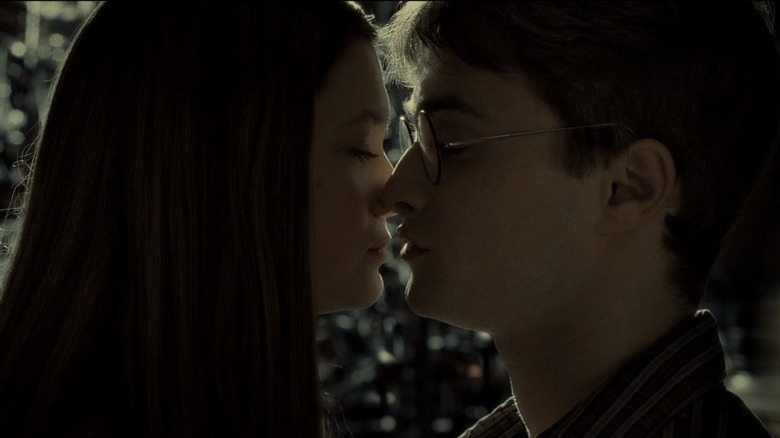

Every woman in the series could do better

You can probably blame the sad state of wizarding education for many of the worst choices made by characters in "Harry Potter." But one thing you can't blame it for are the romantic choices made by pretty much every woman in the series. Ginny ends up with Harry, despite the fact that she's significantly cooler than him — not to mention the fact that he breaks up with her before the final battle, so he doesn't have to feel guilty if she gets hurt. Hermione ends up with Ron, who brings basically nothing to the table in comparison to Hermione's empathy, competence, and intelligence. Remus Lupin treats his relationship with the funny and fascinating Nymphadora Tonks as an unwanted burden. Triwizard Champion Fleur Delacour marries a glorified banker with a cool earring. What little we get of James and Lily Potter suggests that Lily also married down.

Of all the couples in the series, Arthur and Molly Weasley are the only ones who seem particularly well-matched. Even then, however, Molly is the undisputed star of that relationship, not Arthur. And yes, this applies to the villains, too: Narcissa Malfoy absolutely deserves more than her husband Lucius, who is as arrogant as he is incompetent, and as for Bellatrix Lestrange ... well, the less said about that, the better.

Only the straights survive

To the extent that "Harry Potter" has LGBTQ or LGBTQ-coded characters, it is not kind to them. There are only two explicitly LGBTQ characters in the "Harry Potter" franchise: Albus Dumbledore and Gellert Grindelwald. Neither display their sexuality in the text of the story – Rowling announced that they were gay in 2007, after the release of the final book. Their relationship has not been depicted explicitly in the "Fantastic Beasts" prequel films, and both die in the original book series. Rowling has also explained that Lupin's lycanthropy is intended as a metaphor for AIDS, a connection that many readers saw as evidence that the character is gay and, as was frequently argued, in a relationship with Sirius Black. However, that supposition is dashed in "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince," when Lupin (reluctantly, it must be said) agrees to a relationship with Tonks, who gives birth to his child in the next book.

However you feel about Rowling's gender politics, it can't be denied that she goes out of her way to reinforce the straightness of the characters who are most easily read as LGBTQ. Even then, she kills them all anyway — Black in "Order of the Phoenix," Dumbledore in "Half-Blood Prince," and Lupin in "Deathly Hallows."

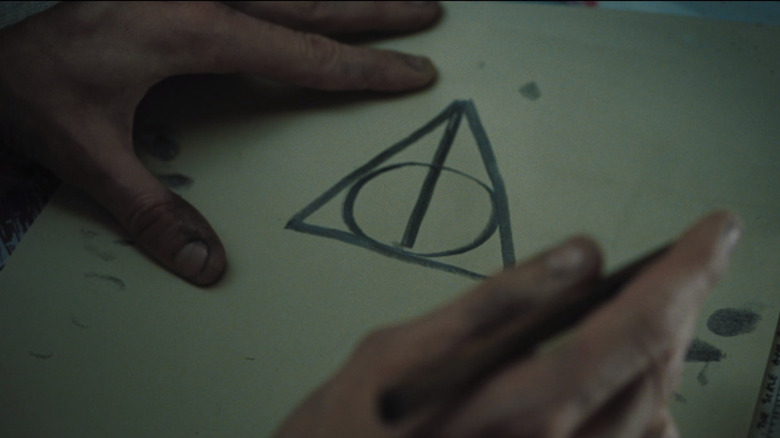

The Deathly Hallows are meaningless

"Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince" does an excellent job of setting up the seventh and final part of the story. Dumbledore, Harry's mentor and protector, has been killed, his final act being to provide Harry with crucial information about Voldemort's horcruxes, the mystical artifacts in which he's concealed his soul. Harry, Ron, and Hermione declare their intent to find the horcruxes and put an end to Voldemort once and for all. All of this makes perfect sense, so you'd be forgiven for thinking that horcrux-hunting is what the last book would actually be about.

Instead, from out of nowhere, we learn about a trio of legendary items called the Deathly Hallows. The last book is named for them, and they play a major role in the story ... except for the fact that they don't actually matter. The Cloak of Invisibility is the same cloak Harry gets in the first book — the fact that it's a Hallow serves only to differentiate it from other invisibility cloaks. The Resurrection Stone allows Harry a moment with his dead family. Harry's possession of the Elder Wand technically helps him kill Voldemort, but it's kind of the cherry of top of all the other reasons Harry defeats Voldemort. Like all the Hallows, it's superfluous. It's bizarre that Rowling decided to jam a previously unknown set of magic items into a finale that already had all the elements it needed to succeed.

Albus Severus is a terrible name

In the notorious "Deathly Hallows" epilogue, we learn that Harry somehow convinced Ginny to name their second son Albus Severus, after Dumbledore and Snape. That seems sweet at first glance, but take a moment to recall the men in question. Albus Dumbledore manipulates Harry constantly throughout his teenage years to turn him into a weapon against Voldemort. We can mostly still buy him as worthy of getting a kid named after him, but Severus Snape? Really, Harry?

Let's recap. Severus Snape is the man who bullied and tormented Harry and dozens (possibly hundreds) of other students instead of teaching them. Severus Snape hates a kid on sight because he was in love with the kid's mom, who married someone else — someone who doesn't join murderous cults bent on her extermination. In fact, Severus Snape is a loyal Death Eater until the day Lily is killed. The "heroic" Severus Snape who acts as Hogwarts headmaster, the era in Snape's life Harry specifically invokes when explaining Albus Severus' name, doesn't even contribute all that much to Voldemort's ultimate fall! Don't name your kid after that guy, Harry. That guy was the worst.