The Untold Truth Of Lost Girl

Sci-fi, fantasy, and horror have long been spaces for strong female characters (Xena, Echo, and Buffy, to name a few). The freedom of building worlds of vampires, demons, and forces of darkness can allow for space to create totally unique characters — including new kinds of powerful women.

With the end of "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" in 2003, there was a void of these characters on TV. Who would be the next demon-fighting, joke-quipping, bad-ass woman? Enter "Lost Girl," the supernatural Canadian show about Bo, a bisexual succubus (a woman who uses sex to feed, heal, and kill) discovering her powers in a world of Fae (supernatural folk), where she encounters monsters, demons, and scariest force of all: love.

"Lost Girl" made a name for itself with its sex positive and non-judgmental take on female sexuality, friendship, and relationships, but the show almost wasn't made at all. Self-funding, network risk-taking, and unexpected help from "True Blood" are all part of the untold truth of this beloved series.

Lost Girl is found

Like many of the best ideas, the pitch for "Lost Girl" was born during a conversation with friends over coffee. Jay Firestone, a Canadian producer known for his work on "La Femme Nikita" (the series), was at a café during the Cannes Film Festival, talking with some friends about what would be different about Buffy if her show were made in the 2000s instead of the '90s. "She'd be bisexual," Firestone joked, and a light bulb went off: he would make a series about a bisexual superhero.

Firestone's elevator pitch: "She's good, she's bad, she's bi." Still, he didn't yet know who this character was until he hired writer Michelle Lovretta to develop "Lost Girl." When Lovretta heard the idea, she immediately thought of a succubus, which is a demon from folklore who takes the form of a woman to seduce men while they sleep and suck their life force from them.

In popular culture, succubi have always been portrayed as evil. Lovretta recognized the misogyny in these representations of "evil" female sexuality and wanted to turn it on its head by creating a sex-positive, empowered show about a woman finding power in all of her relationships — both romantic and otherwise.

A new female superhero

Bo joins a long line of genre female superheroes, but "Lost Girl" was a trailblazer in many ways, not least of which was in the representation of its lead character. Unlike her other genre contemporaries (Buffy, Xena, Sookie Stackhouse), Bo has one key difference: for her, sex is power (literally). According to Lovretta, Bo "has the sex drive of a porn star, the heart of the girl next door and the dating skills of a fifteen year old." Although Bo is bisexual, a fact that set her apart from so many other female lead characters, Lovretta and Firestone didn't want to make this her entire identity.

So, Bo "comes out" as a succubus as she discovers who she is and why people kept dying after she has sex with them, but her sexual orientation is a non-issue in this world. Similarly to Buffy, which used demons and monsters as metaphors for the trials and tribulations of high school and adulthood, Lost Girl uses Bo's identity as a succubus to explore femininity, love, and friendships.

The rules of Bo's world

A show about female sexuality can easily veer into the negative or even misogynistic, so to maintain the heart of "Lost Girl" and stay respectful to Bo's character, Lovretta created internal rules for the show. Along with Bo's sexual orientation being a non-issue, her sexuality and sexual desire were not to be shamed. A succubus is an equal opportunist when it comes to partners, so Bo's male and female partners had to be equally viable; there were no shallow girl-on-girl kiss-of-the-week moments, and love interests of any gender could be (lovingly) objectified. Finally, in this world of succubi, demons, and supernatural folks, monogamy isn't a given and Bo could have sex outside of relationships.

Even after Lovretta's involvement with the show changed (more on that later), these rules remained in place to ensure that the integrity of Bo and the series were always maintained. Lovretta has said that she felt trepidation about taking on a show like this because of the ways it could turn exploitative, which is why she created these rules. And it's a good thing that she did, because they helped make the show what it is.

A Lost Girl with no home

While Lovretta was working on empowering Bo, Firestone was working on selling a show about a bisexual demon who kills people with sex. It was a tough sell, particularly for folks in the U.S., as networks were scared of the bisexual element. So, he used his long-standing career as a successful producer to convince Canwest Global Communications Corporation, a Canadian media conglomerate, to fund the show. Firestone had a good relationship with Canwest as he had sold them their first production company a decade earlier: Fireworks Entertainment, Inc., his company that was known for its focus on genre series and strong female protagonists.

Canwest owned the cable network Showcase, which had been founded to air independent and foreign films. The network quickly gained a seedy reputation, however, with its blocks of erotic and adult programming. Due to licensing requirements, Showcase was obligated to air original Canadian programming in its primetime spots and Canwest wanted to rebrand Showcase to make it more appealing to investors, so they were willing to invest in Canadian shows that could be brought to Showcase. Finally, "Lost Girl" had found its home.

The unexpected effect of True Blood

Even with Firestone's success in finding a network and financing for "Lost Girl," the series still faced some obstacles. But the success of "True Blood" unexpectedly gave the show a helping hand. "True Blood" premiered in 2008, two years before "Lost Girl," and became a wildly popular critical success. Whether you were a genre fan or not, it seemed like everyone was watching "True Blood" at the time, and suddenly, every network wanted in on the genre space. Plus, the fact that a prestigious network like HBO was supporting a supernatural show allowed other networks to take the same risk and pick up a show like "Lost Girl."

Additionally, the darkness and grittiness of "True Blood" pushed Firestone and Lovretta to go in a different direction with "Lost Girl," which was originally conceived to be a bit darker. They decided to take the show in a more lighthearted and fun direction in order to distinguish themselves, which may have contributed to its success later.

Finding the cast of Lost Girl

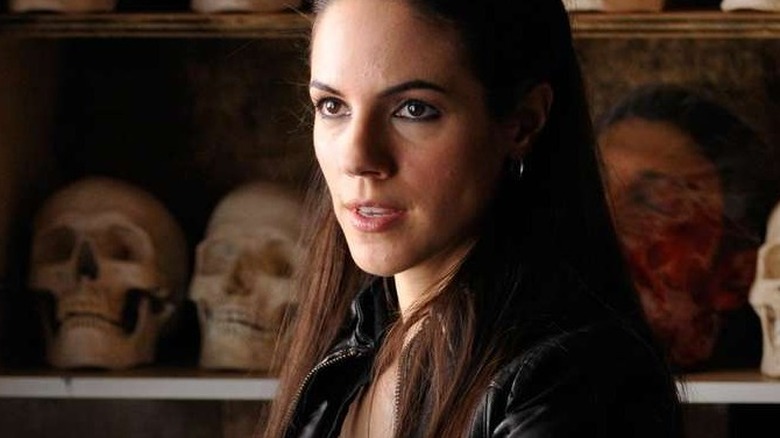

No matter how great the idea, a series is only ever as good as its cast. "Lost Girl" hinges upon its "lost girl," but finding the right Bo was a lengthy process. In fact, producers almost shut down production when they hadn't found Bo after three months of searching. Luckily, Anna Silk sent in a self-tape at the last minute. "Just really sweet and charming," Lovretta said about Silk's audition. In fact, they rewrote the character of Bo to be more vulnerable and fit Silk's approach.

For Lovretta, the friendship between Bo and Kenzi is as important as any of Bo's romantic relationships, so finding the right Kenzi was crucial. It was a no-brainer when Lovretta saw Ksenia Solo's audition and nearly choked on her coffee with Solo's first syllable.

A show about a succubus needs a whole lot of sexual chemistry, and the creators knew they'd found one of Bo's major love interests when they saw Kris Holden-Ried's Dyson. He and Silk kissed so passionately during his audition that they left a crack in the wall after he pushed her against it. With the chemistry written on the wall, Dyson was found.

The pilot that sort of was

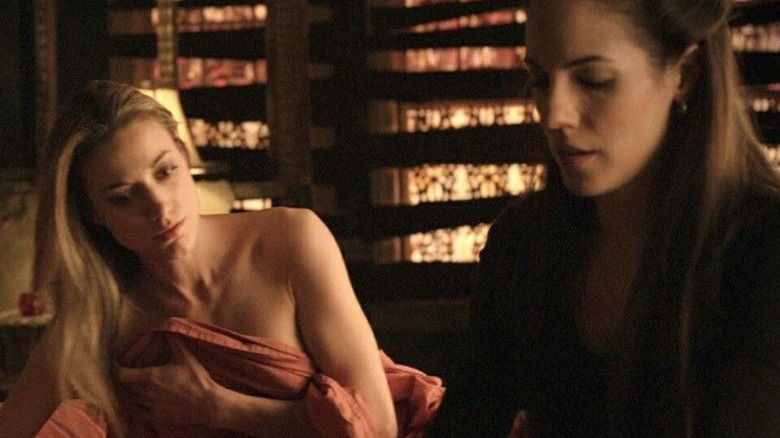

After finding the cast and network support, the creators of "Lost Girl" were ready to film the pilot. Titled "Vexed," it brings viewers on a gritty and dark journey into Bo's world and her ties to her two main love interests, Dyson (a werewolf) and Lauren (a human), alternating between rough sex and tender intimacy.

By the time of filming, "True Blood" had come out and "Lost Girl" was moving in a different direction, so "Vexed" was pushed to episode 8 of season 1 and a more traditional intro-to-the-world pilot was filmed. This wasn't out of the ordinary as the entire first season of "Lost Girl" was shot out of order.

Although Firestone had secured funding for the pilot with Canwest, the media conglomerate was facing potential bankruptcy just a year after commissioning "Lost Girl." Firestone stepped in and shouldered the rest of the financing himself. It was a risk that paid off as the show was picked up in 2009 and Sony Pictures Home Entertainment stepped in to release DVDs internationally.

Musical chairs of showrunners

"Lost Girl" was the brainchild of Firestone and Lovretta, but over the course of its five seasons, it was handed off to several different showrunners. Lovretta was a co-showrunner in Season 1 along with Peter Mohan, a veteran TV producer of "Mutant X" and "Blood Ties." After the first season, Lovretta decided to become more of a "fairy godmother" to "Lost Girl" as she left to pursue other opportunities.

Lovretta and Mohan left on good terms, and Season 2 was put in the hands of "Lost Girl" writer Jeremy Boxen and Grant Rosenberg, producer of "The Outer Limits" and "Eureka." But the game of musical chairs began again as they left after Season 2. Emily Andras, who would go on to develop "Wynonna Earp," took over for the next two seasons. Andras had been brought on as a writer in Season 1 and considered Lovretta a mentor, which helped her feel confident in taking on a genre world, which she hadn't done before. Michael Grassi was given the reins for the fifth and final season of "Lost Girl."

The Lost Girl writers' room

In spite of the changing showrunners, the writers' room of "Lost Girl" maintained an established approach to creating the episodes for each season. Every episode of "Lost Girl" incorporates a different mythological or folkloric figure, but Andras has noted that they were lax in updating the show bible. Lovretta had created a show bible with helpful documents, including a historical timeline since there are some Fae who've been around for thousands of years. It's a lot to keep track of, but Andras pointed out that the story came first and the magic second.

"Lost Girl" looks at real world social issues through the lens of its Fae world, so the writers would decide on an issue for the episode and then find a mythological figure to match that. The writers would break episodes scene-by-scene together, and then that episode's writer would go off to draft the script. Ten drafts and six weeks later, the episode would be ready for the screen.

Filming in Canada

Canada has long been an attractive filming site for American productions due to its tax incentives, low costs, and locations that can stand in for American cities. As a result, there's a substantial supply of great crew and locations available in Canada, which is a big gift when you're filming an alternate world pilot like "Lost Girl" and want it to look as good as possible without completely breaking the bank.

"Lost Girl," however, was a true-blue Canadian original show, one of several local productions that helped Canada become the "sci fi nation." Other Canadian series like "Orphan Black" and "Continuum" joined "Lost Girl" in bringing a world of sci-fi and fantasy to Canada.

Graeme Mason, creator of "Orphan Black," has noted that the versatility of Canadian writers, who work in sci-fi, comedy, and drama, has blurred the lines of genre on TV. Certainly that's the case in "Lost Girl," which made a name for itself as a supernatural show with an appealing mix of both humor and drama.

A supernatural debut

The "Lost Girl" pilot premiered on Showcase in September 2010. It was an immediate success, becoming the highest-rated Canadian scripted debut on Showcase and maintaining strong ratings with the Canadian audience. Lovretta has attributed some of this success to the freedom that Showcase gave them to explore themes of sexuality that might "send other networks into a pearl-clutching panic." The approach of "Lost Girl" paid off, as audiences were hooked by Bo's journey to discover herself and her own sexuality.

"Lost Girl" also benefited from a strong internet presence — its website even featured an interactive motion comic. It turns out that the internet was just the space that the series needed to find its passionate audience and continued success. "From what I've seen on Twitter, we're being watched all over the world," Lovretta said in an interview with Water Cooler Journal during Season 1. "I'm really proud of that, and so grateful to our wonderful fans.

Finding an audience in the U.S.

"Lost Girl" had found success in its homeland, but the question remained: how would it do in America? Firestone and company got the answer after Syfy picked up the first two seasons. U.S. audiences finally got their first glimpse of Bo and the Fae in 2012 when Syfy premiered "Lost Girl."

The standards of what's appropriate for audiences differ between Canada and the U.S., so the "Lost Girl" team was anxious about what changes Syfy would request to make the show appeal to American viewers. However, Lovretta revealed that the team was pleasantly surprised to find that they could continue doing what they wanted without too much interference (other than in the language department, as American networks censor explicit language more than Canadian or some other foreign channels do). That meant that in order to avoid episodes filled with bleeped out words, the "Lost Girl" writers had to tone down some of the curses (sadly, that meant fewer "s**tballs" from Kenzi in each episode).

The Lost Girl faemily

The fans of "Lost Girl" — known as the "Faemily" — elevated the show to a new level. With a bisexual supernatural lead, the series cast a wide net as it drew in fantasy enthusiasts and audiences eager for LGBTQ+ representation, who were thrilled to see an empowered and three-dimensional bisexual protagonist. It remains sadly rare to see LGBTQ+ characters front and center who were allowed to experience their identity in a positive, complex, and non-traumatic way, and "Lost Girl" offered exactly that. Social media offered fans a space to interact, and Firestone noted that people would start talking on Twitter just 15 minutes into each episode.

When the show came to an end with its fifth season in 2015, showrunner Michael Grassi hoped that whoever watched would take away some important messages: "Love is stronger than hate. You can't change the past, but you can learn from it. And most importantly, live the life that you choose." Certainly, "Lost Girl" embodies these messages, which is why the series continues to inspire and draw in viewers over a decade after its debut.