Small Details You Missed In The Shining

Ask 10 people to name the scariest movie of all time, and you'll get 12 answers. Still, few movies have haunted the cultural consciousness quite like "The Shining." The combination of Stephen King's pulpy paperback thriller and filmmaking artiste Stanley Kubrick created something totally unique. That means "The Shining" delivers on the shocks but always seems to suggest something more is going on beneath the surface, even if no one can agree just what it is.

There's the straightforward story of a haunted hotel that turns caretaker Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) against his family, but the chills are so effective and so lasting that viewers have refused to accept it as just another horror movie. Is it really a ghost story, or are the ghosts all in the characters' heads? And is it just a ghost story, or an allegory for addiction, historical genocide, or ongoing government conspiracies? "The trouble with Kubrick's film is that it is so meticulously well composed," Xan Brooks writes in The Guardian. "One has the sense that everything in these crowded frames ... is there for a reason, throbbing with significance. Watching 'The Shining' is like ... a malign version of 'Where's Waldo?' Stare too long and you lose the plot."

We can't offer any answers to what it all means. But we've taken some time to stare at "The Shining" ourselves, and we've come up with a few questions based on all the details hiding inside and outside the frame. Let's see what you might have overlooked at the Overlook.

The cartoon Danny watches foreshadows the climax

Analyzing "The Shining," you'll find critics drawing parallels to a library's worth of highbrow sources from Freud or McLuhan or classical mythology. But don't let that fool you — Stanley Kubrick enjoys good lowbrow entertainment as much as anyone, even if its importance to "The Shining" is just as obscure as any academic text.

We meet Jack Torrance's psychic son Danny (Danny Lloyd) at the dinner table in front of the TV. We can't see what he's watching, but that distinctive "Beep beep!" identifies it as a Road Runner cartoon. And if you've wasted enough childhood hours in front of the "Looney Tunes" cartoons, you might recognize Carl Stalling's score for "Stop! Look! and Hasten!" You may even remember what happens during this scene, with Wile E. Coyote chasing the Road Runner through a maze of intersecting railroad tracks. That makes this scene an exceptionally subtle piece of foreshadowing for the much less fun maze chase Danny endures later in the film.

There's a slightly more obvious example when Danny tunes into "Looney Tunes" again later on. We still don't see what he's watching, but we can hear the theme song for "The Road Runner Show." Lyrics like "The coyote's after you!/ Road Runner!/ If he catches you, you're through" become much more ominous knowing the deadly chase that's coming. Jack even identifies himself as the big bad wolf when he threatens his wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall) later on — and that makes him, if not a coyote, at least part of the same family.

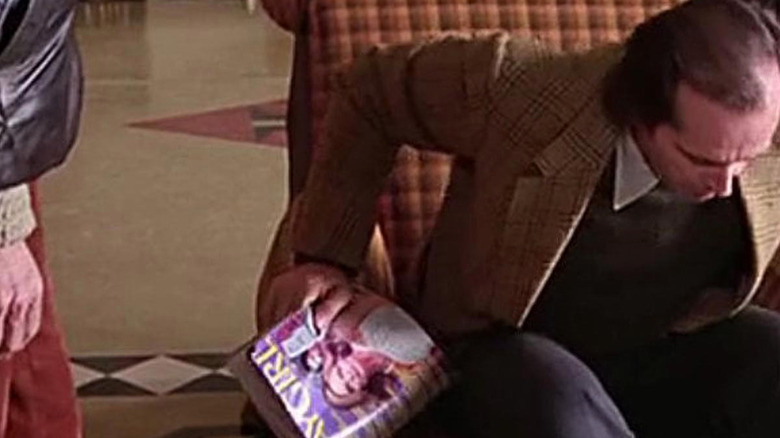

Jack finds some unexpected reading material in the lobby

Not all of the Easter eggs in "The Shining" are full of secret portent and hidden meanings — every once in a while, Stanley Kubrick drops in a little private joke for those viewers who can pick up on it. When Jack Torrance arrives at the Overlook Hotel, he makes himself comfortable in the lobby while he waits for his boss, Mr. Ullman, to show him the grounds. He seems to have found something to keep himself busy, but if you look closely, it's not at all what you'd expect. Jack's lounging with an issue of Playgirl, Playboy's opposite number for readers who prefer their nude models male.

It works well as a subtle raunchy gag, but that doesn't mean it's not open to interpretation. In the homophobic times when "The Shining" was made, homosexual desires were often treated as a sign of deviant psychology — and Jack turns out to be plenty deviant by the time the movie's over. One theorist interviewed in the documentary "Room 237" makes an even bigger stretch. After hunting down the specific Playgirl issue Jack's reading, he analyzed the cover headlines to draw some even darker conclusions about the movie's child abuse subtext than was already visible on the surface.

The Overlook changes shape

The Overlook is one of the most iconic locations in horror, and the closer you look at it, the more horrifying the hotel becomes. At first glance, it seems like it could exist in reality, but it doesn't always add up. Even when Jack Torrance first visits, we see his entire path to Mr. Ullman's office as he goes deeper into the building yet somehow arrives in front of a window that opens to the outside. When the hotel's psychic chef Dick Halloran (Scatman Crothers) gives Wendy and Danny a tour of the freezer, they exit into a different hallway than the one they entered from. These are just a few examples – fans have made exhaustive catalogs of all the spatial impossibilities in the hotel.

"The Shining" was filmed on multiple sets over an entire year, so some of these inconsistencies could be honest mistakes. But according to producer Jan Harlan, "The set was very deliberately built to be offbeat and off the track, so that the huge ballroom would never actually fit inside. The audience is deliberately made to not know where they're going." Even if you can't keep track of all the spatial hiccups, they can still play on your unconscious impression of "The Shining." The inside of the Overlook starts to feel like the tangled hedge maze outside. Or, as critic Nathan Rabin describes it, it forces you to share Jack's alcoholic mindset: "The film's famously disorienting approach to space and time re-creates on a stylistic and emotional level the confusion and helplessness of being deeply and unhappily inebriated and out of control."

The Overlook has a magical double meaning

Nothing in "The Shining" is what it seems, but a first glance, the name of the Overlook at least seems straightforward. What could be a better name to entice people to a hotel that offers a scenic overlook of the mountains? But even that turns out to be more complicated than it seems. Critics have interpreted the movie in terms of what the characters "overlook" — or don't see.

But there's another, more obscure meaning of the word that may be just as relevant: There's a concept in folklore called "the evil eye," a glance that has a magical power to curse its victim. And believers in the evil eye describe the act of giving it to someone as "overlooking." That certainly fits the accursed atmosphere of the Overlook Hotel. It's especially fitting in Stanley Kubrick's adaptation, since the director has always been obsessed with eyes, to the point he created the "Kubrick stare" — brows and head lowered but eyes raised. It's certainly hard to describe the look Jack Torrance gives the audience in many chilling scenes as anything but an evil eye.

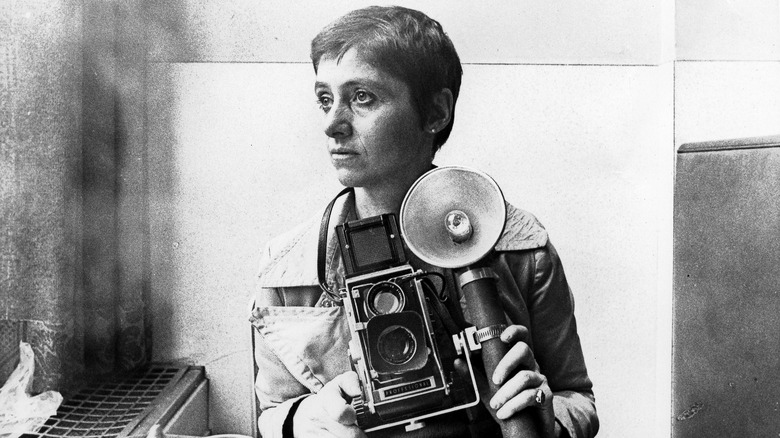

The Grady girls are a tribute to a master art photographer

There are plenty of chilling images in "The Shining," but there's nothing quite as iconic as the two girls in matching blue dresses standing at the end of the hallway, repeating, "Come play with us, Danny. For ever. And ever. And ever." It's one of Stanley Kubrick's greatest achievements, but he can't keep credit for it all to himself. His assistant Leon Vitali brought him a photo by Diane Arbus of two sullen dark-haired twins in matching clothes, holding hands and looking straight into the camera just like the Grady girls.

Arbus' legacy would already be assured even if she hadn't inspired one of the classics of horror. Throughout the '60s, she turned her camera on a variety of people who were on the margins of society, whether because of poverty, disability, or alternative lifestyles. Her approach was just as unusual as her subject matter, creating a strange atmosphere that was both surreal and deeply mundane that became hugely influential. Kubrick would have been especially drawn to her work as a former fine-art photographer himself — his early photos of circus performers have even drawn comparisons to Arbus.

The Grady twins aren't twins

The creepy children Danny Torrance meets in the hall are often described as "the Grady twins," but there are some details in "The Shining" that show that's not the case at all. When Mr. Ullman retells the story of their murder, he goes out of his way to mention that they were "eight and ten years old." But aside from that one line, it's hard to see them as anything but twins — they're the same height, they seem to operate as a single unit, and the actresses who played them are twin sisters in real life.

So is Ullman's description of their ages a mistake? Well, maybe, but not necessarily by the filmmakers. Roger Ebert used the twins' shifting age as part of his argument that we can't trust what we see because it's filtered through the characters' perspectives: "Although we know there was a two-year age difference in the murdered children, both girls look curiously old. If Danny is a reliable witness, he is witness to specialized visions of his own that may not correspond to what is actually happening in the hotel." Even if Danny's "shining" is real, the ghosts it allows him to see may not be. Could the Grady sisters appear to Danny as twins because Danny, not knowing their real ages, imagines them that way?

There are too many Gradys

Jack Torrance experiences a haunting of his own when he goes to the bar and finds the supposedly empty hotel crowded full of people. One of them is his predecessor, Delbert Grady. Or is he? When Mr. Ullman describes the Grady murders, he says the caretaker's name was Charles. That may explain why Delbert denies being the murderer Jack heard about, but he contradicts himself a few moments later, in his own euphemistic way. He never admits to murdering his girls, but he does say, "I ... corrected them, sir. And when my wife tried to prevent me from doing my duty, I ... corrected her, too."

So if both Gradys are the same, does that make the name change a mistake? Or is something stranger going on? Ullman says the murders took place in 1970, but here Grady is at a party full of Roaring '20s-era ghosts. Could two Gradys have worked at the Overlook at different times, and both murdered their families? The chilling ending, where a photo from 1921 shows Jack front-and-center, raises further possibilities. Could both caretakers be reincarnations of earlier hotel staff, doomed to repeat the same cycle of violence over and over again? Or could the hotel somehow exist outside of time, absorbing Jack and Grady into its history after it corrupts them?

The Grady girls had a good reason to burn down the Overlook

Mr. Ullman only briefly skims over the history of the Grady murders, but the ghostly Grady himself offers more detail, including one that's deeply significant but just as easy to miss: He says that his daughters were uncomfortable in the Overlook and that he had to kill them because one stole a pack of matches and tried to burn it down. That could easily just be childish mischief, but it may have actually been the most heroic thing the girls could have done. Jack Torrance's inner demons and the ghosts haunting the hotel seem to be responsible for the horrors we see, but there are also hints that the hotel itself is behind the family's nightmare.

Dick Halloran tells Danny, "You know, some places are like people. Some shine, and some don't. It's just that the Overlook Hotel has something like shining." And if you're familiar with Stephen King's novel, you'll know that the author developed the idea of the hotel as a conscious entity influencing all the murders that took place there in much more depth. With that in mind, the Grady sisters could easily have been trying to burn down the hotel to save their family. And just as easily, the hotel could have tempted their father to kill them to save itself.

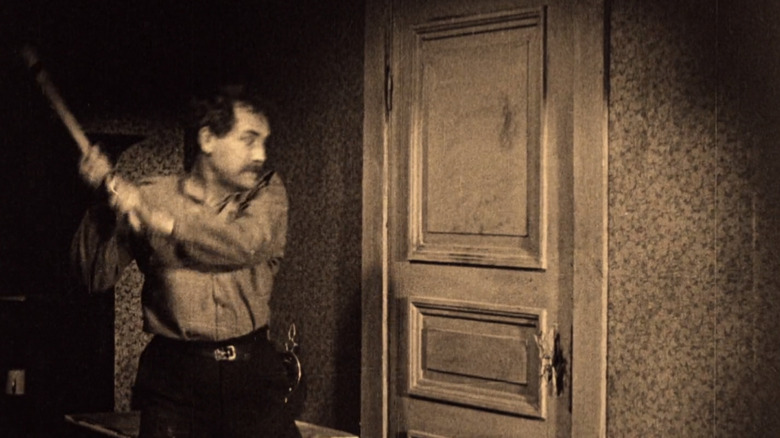

One scene is taken shot-for-shot from a silent classic

It's hard to imagine any filmmaker but Stanley Kubrick coming up with a scene as intense as Jack Torrance whaling away on the door intercut with Wendy's terrified reaction. But another filmmaker could and did, 60 years before Kubrick lifted the scene shot-for-shot.

In 1921, Swedish director Victor Sjöström adapted Selma Lagerlof's novel of a dying soul looking back on his past life as "The Phantom Carriage." On New Year's Eve, the last man to die has to drive Death's carriage for the next year, and this year, that man is David Holm. Like Jack, he is an abusive alcoholic, and the previous coachman takes David on a tour of his life. Sjöström doesn't pull any punches about the sins David has to atone for. When David comes down with tuberculosis, the only way his wife can keep him from spreading it to their children is to lock him in the kitchen. Even that's not enough for the stubborn drunk, and he smashes his way out with an ax, terrifying her so much she faints. The two scenes are almost identical.

But if you have to steal, you might as well steal from the best. Sjöström made many classic films in both Sweden and Hollywood, and he was considered the country's greatest director — until a young talent named Ingmar Bergman came along and gave Sjöström the starring role in his 1957 breakout success "Wild Strawberries."