The Little Mermaid: Things You Missed As A Kid

It may be hard to believe now that Disney is the biggest studio in the world and cartoons frequently lead box office tallies and TV ratings, but in the '70s and '80s, animation was barely hanging on all over Hollywood, and at Disney in particular. Cartoons were strictly cheapo Saturday morning filler, with the occasional big-screen outing rarely getting much attention. That all changed with the back-to-back smashes "Who Framed Roger Rabbit?" and "The Little Mermaid" in 1988 and 1989. Suddenly, 'toons were on top of the world again, and Disney was on top of them all.

"The Little Mermaid" set the tone for Disney's future successes with its timeless story of a princess, Ariel, looking for love with the help of cute animal sidekicks and opposed by an unforgettably over-the-top villain — accompanied by a bestselling Broadway-style score. That kid-pleasing formula means that, as much as any of its imitators, "The Little Mermaid" has been a major part of multiple generations' childhoods. It's so formative that many of its young fans have gone back to revisit it as adults, and they often find more in "The Little Mermaid" than they remember. Here are some of our favorite discoveries that younger audiences might have missed.

Ariel's name has Shakespearean origins

The first things many adults will notice upon returning to "The Little Mermaid" after a high-school education are the multiple literary origins of the heroine. The name "Ariel" originally belonged to a character from "The Tempest." William Shakespeare's play tells the story of Prospero, the banished Duke of Milan who uses his occult knowledge to get revenge on the men who betrayed him. He gets help from the two supernatural servants he met on the island where he washed up after his exile: the monstrous Caliban and the mischievous Ariel.

While Ariel enjoys power over the water, most productions portray him (or sometimes her) as a spirit of the air. That makes more sense when you look at the Disney film's more direct source material, the original short story by Hans Christian Andersen. His version doesn't go for Disney's fairy tale ending — the nameless literary mermaid needs to win the prince's love in order to secure an immortal soul, and when she fails, she melts into sea foam. But she's rescued by the children of the air, spirits like Shakespeare's Ariel who give the mermaid a second chance at eternal life.

There are parallels between "The Tempest" and Disney's "The Little Mermaid," too. Both Prospero and Triton are overbearing fathers who try to keep their daughters from their true loves, whom each meets due to a shipwreck before learning their lesson in the end. And the animated movie isn't lacking in tempests of its own, either, even ending with one created by magic just like Prospero's.

Familiar faces hide in the background

Drawing a feature-length animated movie one frame at a time is a long, painstaking process. So it's no wonder animators would amuse themselves by hiding private jokes in the margins of those frames, especially when they're as packed with detail as in "The Little Mermaid." This means there's a lot that kids will never see and even adults may need a sharp eye and a quick finger on the pause button to catch.

For instance, the scene of King Triton's lavish musical presentation is packed with thousands of mermaids, mermen, and other sea creatures. But if you squint, there are some other characters who look way more out of place — Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and Goofy. And if you keep looking, you might spot another familiar face: Jim Henson's lovable puppet Kermit the Frog, possibly included as a reference to Disney's then-ongoing negotiations to buy out the Jim Henson Company, which wouldn't be resolved until 2004.

Later on, the animators sneak in another cameo that's easier to catch but harder to recognize. The showstopping "Under the Sea" number ends with a ring of fish holding out their fins to Ariel before realizing she's vanished. There's one little blue guy in the crowd with glasses and exaggerated lips. Who's that? Well, older viewers may recognize him from the 1964 musical "The Incredible Limpet," where "The Andy Griffith Show" star Don Knotts gets turned into an animated fish.

Flounder looks nothing like a flounder

Ariel's best friend is a little fish named Flounder — but what kind of fish, we're not sure. We know he's not a flounder, because flounders aren't cute at all. They're weird, ugly bottom feeders with both eyes on the same side of their face. And just to make it weirder, they're born looking like normal fish, but their eyes migrate around to the same side as they get older. Other than both being fish, there's no resemblance between Flounder and a flounder at all. The character is brightly colored, but real flounders are dull brown. Flounder is chubby, but real flounders are almost completely flat.

So what does that make Flounder? Fans have theories, and one of the most likely is that he's a sergeant major, which can have yellow and blue stripes like the animated critter. That just raises further questions, though, since like most of the brightly colored cast of "The Little Mermaid," sergeant majors live in the tropics. Prince Eric's kingdom, however, seems to be somewhere in Europe. Then again, real fish can't talk or sing either, so maybe we'll just have to let this one slide.

Ariel has a painting by an old master

The artistry of the best Disney movies doesn't come out of thin air. The animators and background artists have obviously studied the masters. And they're keen to show off their knowledge, even if kids aren't likely to appreciate it. Ariel's collection of land-based artifacts is mostly random junk, but she somehow managed to snag a bona fide masterpiece as well. As she sings "Under the Sea," she contemplates a painting of a woman with a candle and asks, "What's a fire/And why does it/What's the word?/Burn?"

That painting is real: "Magdalene with the Smoking Flame" by Georges de la Tour. Born in France in 1593, La Tour was heavily influenced by the Italian painter Caravaggio's advances in realism and dramatic lighting effects. La Tour took those ideas further, making his trademark dramatic paintings like this one, often lit by a single candle (including, fittingly enough, several paintings of Saint Sebastian). He wasn't recognized in his time, but you can draw a straight line from de la Tour's "tenebrist" style to photography and film: "The Little Mermaid" is far more moodily lit than later Disney films, and according to DVD commentary, the realism of the underwater setting required extensive lighting and animation techniques.

How did little Flounder get that huge statue into Ariel's cave?

When Ariel first sees Prince Eric, he's celebrating his birthday onboard a ship, where he receives a statue of himself. He's not too impressed, but Ariel is, and when the statue goes overboard in a storm, Flounder is thoughtful enough to add it to Ariel's collection of surface stuff. That statue becomes important later when Triton discovers and destroys Ariel's collection, and the shattering of the statue disturbs her most of all.

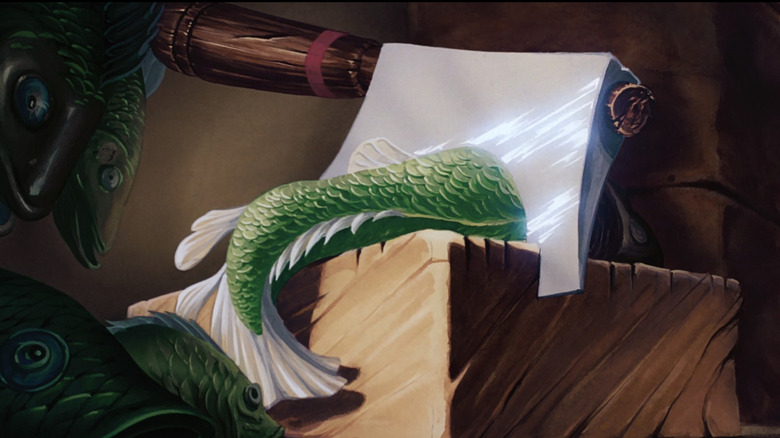

The fairy tale logic of "The Little Mermaid" goes a long way, and we never question most of the impossible things that happen because viewers, especially little ones, are too invested in the story to apply real-world rules to it. But sometimes you notice something that doesn't add up and you can't stop thinking about it. For instance: How does that statue get there? Flounder's about a foot long, with tiny little fins that don't seem to work like human hands. How exactly does he manage to carry a life-sized, solid rock statue all the way into Ariel's cave? The filmmakers seem to have realized how unlikely this whole situation is, because they never even try to show Flounder lugging the statue around. It simply appears in the cave, leaving it to us to fill in the gaps, or realize fifty-odd viewings later how un-fill-able they are.

Ursula is an underwater Divine

Ursula is one of the most fabulously unforgettable Disney villains, and possibly one of the most beloved characters the studio ever created, period. She's voiced with infectious glee by Pat Carroll, but fans have another actor to thank for Ursula's persona, one you'd never think would come within a million miles of a Disney production.

Glenn Milstead was already the belle of the Washington, D.C. drag circuit when he met provocateur auteur John Waters. Waters dubbed him Divine, cast him in his no-budget underground movies, and made him a star in the outrageous "Pink Flamingos" as the "filthiest person alive." This was the beginning of a beautiful friendship, and the Divine-Waters collaboration continued through classics including "Female Trouble," "Polyester," and "Hairspray." To most of America, Divine was an obscure oddity, but to the gay community, he was a star.

And that community included "Little Mermaid" songwriter Howard Ashman, who immediately connected to one of the hundreds of mooted designs for the sea witch — one that looked an awful lot like Divine. That influence extended to Ashman's campy musical number "Poor, Unfortunate Souls" (a phrase Divine says almost word-for-word in "Pink Flamingos"). Divine himself never lived to see it, but both Waters and Divine biographer Jeffrey Schwarz agree he would have loved it. "He would have wanted to play the part himself," Schwarz says.

Ariel's transformation requires some carefully concealed nudity

"The Little Mermaid" was Disney's return to the pinnacle of good, clean family entertainment. But the story posed some problems in that department. When Ariel grows legs, that means she has to grow other, less screen-friendly body parts. And she doesn't grow a skirt to go along with them, either because that'd be too implausible even for this movie or because it'd be too out-of-character for the sadistic sea witch to give her one.

The film required a lot of very careful lighting and camera angles to get to the scene where Ariel finally makes herself a dress out of an abandoned sail. She's silhouetted as she swims to the surface, and when she gets there, there are numerous precisely placed rocks and camera angles that keep the movie G-rated. Even when we see Ariel's face light up as she looks at her new feet, we don't see much of anything else. Kids would take all this for granted, of course, but adults should catch on pretty quick to how much work the animators had to put in to keep things clean.

The kitchen scene is straight out of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre

Like most Disney movies, "The Little Mermaid" treats its animals like people. Sebastian can sing and dance better than most humans you'll ever meet, and when Flounder nearly gets eaten by a shark, you're supposed to care whether he makes it out alive.

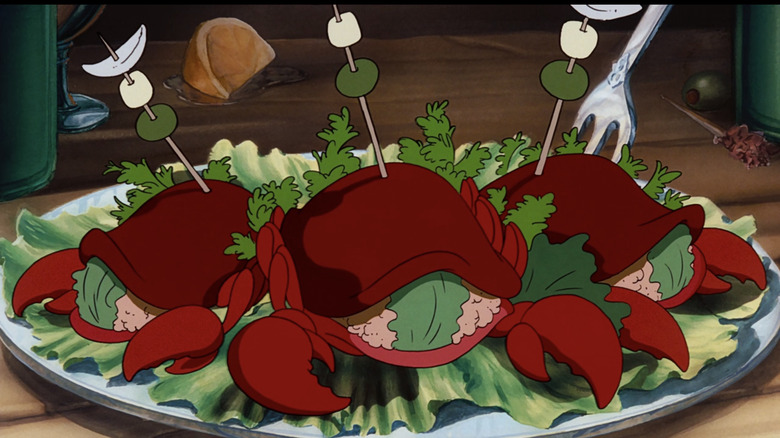

But if you take that kind of thinking too far, "The Little Mermaid" turns into the most appalling kind of horror movie. When Sebastian follows Ariel into Eric's palace, he accidentally finds himself in the kitchen. He discovers piles of dead fish, hollowed-out crab shells, and a cook who gleefully disembowels sea creatures right in front of the luckless crab and chases him around the room with a meat cleaver.

It's all good, zany slapstick fun until you take Sebastian's perspective just a little further. These unfortunate casualties could be his friends and family! Can you imagine any live-action kids' movie showing dozens of hollowed-out human corpses? A severed head bouncing in the hero's face? A corpse being messily disemboweled, even if it's in silhouette as it is here? The sea creatures in "The Little Mermaid" are human enough in every other way. But fortunately, all but the most morbidly inclined kids probably won't make that leap.

Triton's never actually proven wrong about humans

The anthropomorphized fish in "The Little Mermaid" may be cute, but they also raise more questions than the target audience is probably ready to answer. King Triton tries to keep Ariel and Eric apart because humans are "all the same! Spineless, savage, harpooning fish eaters, incapable of any feeling!" We're not exactly thrilled to agree with a character who's clearly horrifically abusive to his daughter (until he learns his lesson), but we can't argue with this point.

All the fish in "The Little Mermaid" have the same thoughts and feelings as humans do in real life, but the surface dwellers go right on slaughtering and eating them. And even when Triton admits he's wrong in the end, he's never actually proven wrong — if fish are intelligent beings, then humanity is still guilty of mass murder and cannibalism. Triton is still right. It makes you wonder just what atrocities Ariel will be participating in when she joins them. Well, maybe she and Eric can go vegan.

Even though this conflict is never resolved, most kids will still go along with it: Humans can't be evil, because we're humans. And as Kurt Cobain told us, "It's okay to eat fish because they don't have any feelings." But what does that mean in a fantasy world where fish do have feelings? That's a question much too dark for this movie to answer.

Ariel recreates an iconic tribute to her source material

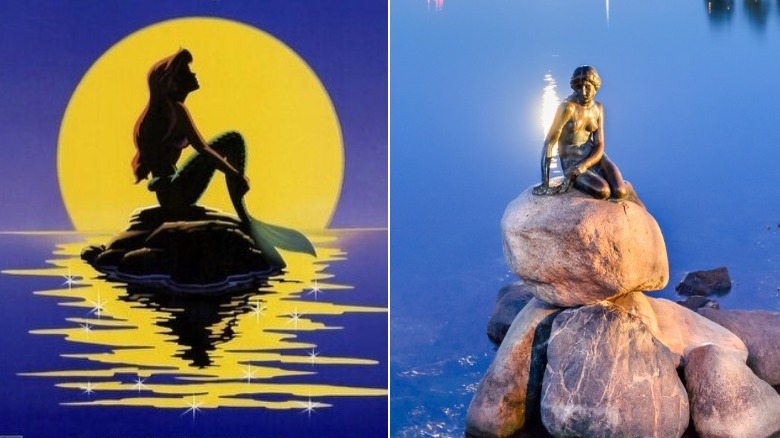

Disney's "Little Mermaid" doesn't share much more than a name with the Hans Christian Andersen story. Andersen's tragic story of unrequited love becomes a simpler fairy-tale romance, with Disney cramming in the comic relief sidekicks and evil villains that are so important to its formula. That's almost blasphemy in Andersen's homeland of Denmark, where the story is so beloved that it inspired a national monument — but Disney at least acknowledges the importance of that landmark in their own adaptation.

In 1913, brewer Carl Jacobsen commissioned Edvard Eriksen to sculpt Andersen's heroine in bronze. Incorporating a real boulder, Eriksen recreated the scene where the mermaid perches on a rock to watch the prince from afar. That's probably why Disney's Ariel is so fond of boulders, perching on one multiple times, including in the iconic shot where she reprises the chorus of "Part of Your World" while a wave crashes behind her. The film's marketing put Eriksen's icon front and center, with a minimalist poster showing Ariel silhouetted in a pose almost identical to the famous statue.