The Untold Truth Of Mystery Science Theater 3000

Created by stand-up comic Joel Hodgson, MST3K had an elaborate premise: a janitor named Joel (Hodgson) is launched into space and forced to watch bad movies as a form of torture while aboard the Satellite of Love. Among the villains: Dr. Laurence Erhardt (Josh Weinstein), Dr. Clayton Forrester (Trace Beaulieu), TV's Frank (Frank Conniff), and Pearl Forrester (Mary Jo Pehl). To keep himself company, he builds chatty robots Crow (Trace Beaulieu) and Tom Servo (Weinstein, and later Kevin Murphy), and together they watch the movies and stay sane by making fun of them at a lightning-quick pace. It was all broken up with Hodgson's inventions and sketches involving a wide array of characters. Nearly 200 episodes were made, and it's about to come back in the form of a Netflix reboot with a brand new cast. Here's a look into Mystery Science Theater 3000.

Elton John inspired the show

Back in the '70s, Joel Hodgson bought the 1973 Elton John album Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. The double-LP's gatefold and inserts included lots of art, including an image illustrating the song "I've Seen That Movie Too." "They had a man and a woman in theater seats at the bottom of the picture and they were watching a Clark Gable movie or something," Hodgson says. "And I remember looking at it and saying, 'That would be an awesome idea for a TV show. You could use a green screen and have these people sit in silhouette and talk during the movie.'"

Joel Hodgson wanted to make "the cheapest show possible"

With an act that included bizarre homemade inventions and contraptions, Joel Hodgson was one of the hottest rising comics in America in the mid 1980s, appearing multiple times on Late Night with David Letterman, Saturday Night Live, and an HBO Young Comedians special. But then, still in his early 20s, Hodgson decided to retire from stand-up and move from Hollywood back to his hometown of Minneapolis. The reason: "After doing stand-up, agents usually plug you into sitcoms. I didn't really want to do that. I got offered a job on a sitcom, and I just didn't think it was funny."

Back in Minnesota with enough money in the bank to live on, Hodgson killed time by making robots out of found objects he bought at the Salvation Army. He struck upon the idea of making his own show, but it would have to be "the cheapest show possible, and that way," he says, "you wouldn't need money, you wouldn't need to talk anybody into it, you wouldn't need approval." That's when he remembered his idea for the people talking back to a movie, and with host segments added in. For the host's companions, Hodgson took inspiration from the science-fiction classic Silent Running. That 1972 movie is about a man drifting through space with three robots—so Hodgson built three robot puppets named Crow, Tom Servo, and Gypsy.

It started in Minnesota, and wasn't very popular

Jim Mallon was the production manager at KTMA, a tiny UHF station in Minneapolis-St. Paul, whose programming, like most UHF stations at the time, consisted of reruns of old sitcoms and very cheaply produced local shows. He hired a guy named Kevin Murphy to help him find local talent for new shows, and so they approached Hodgson, who was something of a celebrity because of his comedy career. Hodgson was very interested in making a show, as he'd already been toying around with the concept for MST3K. Mallon liked the idea, and Mystery Science Theater 3000 debuted on Thanksgiving Day 1988.

Essentially produced to fill a two-hour hole in the KTMA schedule on Saturday nights, Mystery Science Theater 3000 was canceled after one season in 1989. It may not have been a massive hit, but it was a cult hit, popular enough to pack a "thank you show" for fans at the Comedy Gallery in Minneapolis. The assorted parties who both worked on and performed on the show—Mallon, Hodgson, Murphy, and Trace Beaulieu—thought that was that. Until HBO announced that it was interested in reviving the show for a new all-comedy network it was developing called The Comedy Channel. MST3K became one of its first shows in late 1989 (the network was soon renamed Comedy Central). And while the show went big-time, the production stayed put: all episodes were produced in Minnesota, not Hollywood.

It used to be improvised (until it was intricately written)

In the early days of the show, Hodgson and company just made up the jokes as they watched the movie during taping. "We didn't write a script until we had done, like, 20 shows," Hodgson says. "'Good script' doesn't always equal 'good product.'" That's when Hodgson decided the show should be more intricately planned, and he started hiring writers, including Mike Nelson (who later replaced him as host of the show). The staff now had to write the show, watching the movies in advance, and pitching and writing as many as 600 jokes before deciding which ones would make it onto the air. "We were really entertaining ourselves first," says Mallon. "And if the group liked it, there were enough divergent personalities that if we all kind of liked the humor there, it went in." Hodgson adds that there was an "open architecture" in the writers room, and that if anybody didn't like a joke or found if offensive, it was removed from consideration, "no questions asked." "It was 90 minutes long, two hours with commercials," says Trace Beaulieu. "It wasn't like we were a 22-and-a-half-minute sitcom where everything is so intensely scrutinized; there was space.

It was almost called Mystery Science Theater 2000

Of course, they couldn't have a show without a title. As the show entered production in 1988, Mallon asked Hodgson what he wanted to call it, and, "without blinking he said, 'Mystery Science Theater 2000.' But since we were so close to the year 2000, we decided to shift it up one thousand years," Mallon says. Hodgson liked that idea, because he thought it would be funny. "The 3000 was a joke on all the people that were attaching the year 2000 to various programs. In the late '80s it was everywhere: 'America 2000' was something George Bush Sr. was talking about a lot, so I thought, 'Wouldn't it be cool if I name it 3000 just to confound people?'" As for the rest of the name, the "theater" part is obvious, because the show was a showcase for old movies. The "mystery" and "science" parts have their genesis in Hodgson's old gadget-oriented stand-up act, in which he said his devices were created in "the mystery science lab,"

How the robots got their names

Hodgson built the original versions of the Satellite of Love's resident robots himself, and he also gave them their names. He named the "big and slow" robot Gypsy because it looked like a pet turtle his brother had once had, which had been named Gypsy. Hodgson got Crow's name from several sources. First, it's the name of a Native American tribe, and he wanted one of his robots to have "sort of a Native American feel." He also took inspiration from a wild college friend named Tommy Crow and the Jim Carroll Band's song "Crow." And while a servo is a common component in robotics, the name of MST3K's Tom Servo only indirectly relates to that. "The name Servo came from a vending machine at the Southdale shopping center in Minneapolis," Hodgson says. "They had this great vending machine that was shaped like a robot called Servotron. I just pulled Servo from that." The show's initial puppeteer, Josh Weinstein, added in the "Tom."

How they selected which movies to parody

The title of the show required that the creative team generally picked bad science-fiction movies to skewer, or at the very least B movies. The golden age of both bad sci-fi and B movies was the mid-20th century, the 1940s through the 1970s, so most of MST3K's selections date to that era. But what specifically got a movie onto the show? A movie had to be "really bad, but at least watchable and with somewhat of a plot," said Frank Conniff, a cast member (TV's Frank) and writer whose job it was to pick the movies. He estimates that for every one movie that was made into an episode, he rejected about 20 others. (Conniff's pick for the worst movie he ever had to sit through in the screening process: Child Bride, a 1938 movie about old men marrying little girls in a rural town.)

And he had to watch every movie all the way through. During the second season, he approved a movie called Sidehackers after only partially viewing it, only to realize when writing jokes for the movie that it contained a rape scene. (They'd already paid for the rights and had written so many jokes that the staff decided to just cut that scene.) But once in a while, even if the movie was bad enough and suitable for television, things could go wrong. The show was ready to enter production on an episode making fun of the 1978 movie Moment by Moment, a drama about a May-December romance starring John Travolta and Lily Tomlin. But the rights to the movie were "yanked at the last minute," says Mike Nelson.

The MST3K feature film was a disaster

The hosting segments for the season 7 episode sending up The Incredible Melting Man concerned Crow selling his screenplay (Earth vs. Soup) to a big movie studio, only for his captors (Pearl Forrester and Dr. Clayton Forrester) to take control. They interfere disastrously, demanding Crow shoot the movie himself for $800 and to also put Kevin Bacon in it. Mary Jo Pehl (Pearl) says the segments were "an exercise in healing after our struggle" to make the real-life Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie. With a cast and crew used to doing their own thing since the show's days on a UHF channel in Minnesota, "working with the studio and all the attendant politics and creative roadblocks was really, really frustrating. We didn't have the freedom to be as irreverent and eclectic as were in the TV show." Among the things Universal did to sink the movie: stationing studio executive in the writers room, suggesting that there be fewer jokes in the movie, and releasing it to only 26 theaters nationwide its first weekend. It made a mere $1 million at the box office. (And all this came after another movie deal fell through. Paramount wanted to make a MST3K prequel movie exploring the back stories of all the main characters.)

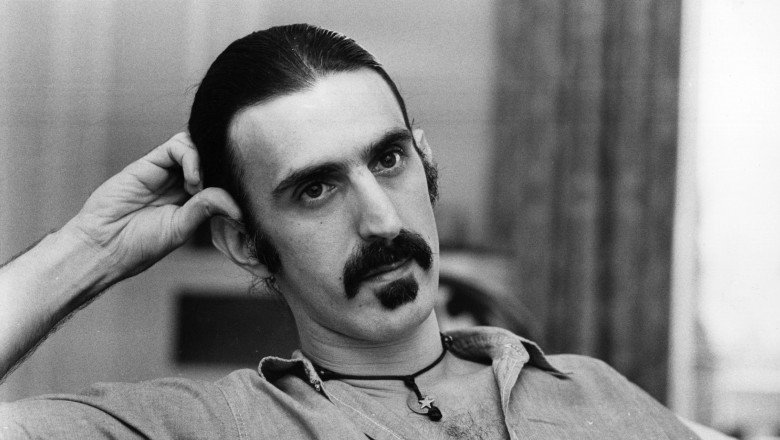

The crew almost made a movie with Frank Zappa

Among the adoring cult of MST3K fans was experimental rock musician—and B-movie buff—Frank Zappa. One night in the early '90s, Zappa was watching TV and came across an episode of MST3K in which a guy in a clown nose was cooking a puppet on an open fire. He thought that was funny, and loved the show even more when the hosting segment (Joel Hodgson was the clown; the roasting puppet was Tom Servo) segued into making fun of an old movie. Zappa managed to call the show's production offices and told the cast and crew how much he loved the show. The admiration was mutual, and plans were drawn up for Zappa and some of the show's creative staff to develop an old fashioned cheesy sci-fi movie about a giant spider "told from the spider's point of view." Sadly, Zappa died in 1993 and the movie never got made.

It was canceled in 1999, but it never really died

Like a monster in a movie one might see on MST3K, MST3K was killed off by the SCI FI Channel in 1999...but it rose up again, still full of life. As it had switched channels before, the possibility of moving the show to a new network was discussed, and 145 fans paid to run a full page ad in Variety to drum up interest. That didn't work out, and the idea to continue the series directly on home video was deemed financially unfeasible. But the creative team behind the series kept making fun of movies elsewhere. Writer and host Mike Nelson teamed up with Kevin Murphy (writer/voice of Tom Servo) to start RiffTrax, which makes MST3K-style commentary tracks for specific movies that can be downloaded and played alongside movies. They've also done live performances (but without the robots). In 2007, another contingent from MST3K—Joel Hodgson, Trace Beaulieu, Josh Weinstein, Frank Conniff, and Mary Jo Pehl—created a similar enterprise called Cinematic Titanic. (Again, no robots.) But wait, what about the robots? In 2007, Crow and Tom Servo re-emerged in the Flash-animated web series The 'Bots are Back. Only four episodes of the robots having their adventures were released.