Movies Like Requiem For A Dream For Fans Of Psychological Dramas

If you asked 100 people what makes a good movie, you'd probably get 100 different answers. While it always depends on mood and context, some people naturally gravitate to films that make them laugh until their sides hurt. Others prefer flicks that keep them on the edge of their seats the whole time. Certain audiences are even drawn to upsetting features.

For fans of psychological dramas, the best movies sneak their way into the viewer's subconscious while at the same time exposing the mental and emotional states of the characters. These movies often inspire a raw vulnerability that often borders on discomfort, and the questions they raise about life, identity, and the human condition linger with the audience long after the closing credits.

Darren Aronofsky is famous for directing some of the most notoriously visceral psychological dramas in the modern canon, like the 2000 film "Requiem for a Dream," which traces the lives and emotional states of four individuals as drug addiction propels them toward delusion and disaster. Bleakly surreal and immensely thought-provoking if you can stomach it, this film sets a high standard for penetrating psychological fare — one that each of the following films charts its own twisted path to meet.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

If you're looking for a movie that will make you laugh and still leave you feeling like you've been punched in the gut, "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" might be the psychological drama for you. Starring Jack Nicholson as Randle McMurphy, this film follows an eccentric ensemble of patients in a mental institution as they struggle to find joy and identity under the thumb of the tyrannical Nurse Ratched.

McMurphy's presence injects a new sense of vigor into the patients' lives, and he becomes an almost mystical figure and a symbol of hope for all of them: He seems immune to the disciplinary methods that have kept the other patients subdued for so long.

As these dynamics and power struggles develop, one of the most compelling aspects of the film is the way it explores each person's brand of "insanity" with tenderness — and questions the utility of the label itself. A poignant example is the case of Billy Bibbit (Brad Dourif), who commits himself voluntarily to the institution because he knows he isn't in the right state of mind to handle life on his own.

There's a sense of tragic vulnerability surrounding each of the characters and their eventual fates. Like the characters in "Requiem," their stories arise from a combination of social and self-made adversity, though the portrayal of these factors in "Cuckoo's Nest" is much more sympathetic.

Black Swan

Darren Aronofsky has made such a name for himself in the arena of psychological drama that a couple of his other features have deservedly landed on this list. They're all worth watching, but "Black Swan" is one of the most exquisite, merging elements of horror, folklore, and dance on a devastating journey into madness.

The cast of this film is stacked with talent, with Mila Kunis and Natalie Portman starring as two dancers competing for a role in Tchaikovsky's "Swan Lake" ballet after the prima ballerina (Winona Ryder) is indisposed. Portman's Nina is the fragile, demure embodiment of the White Swan role, whereas her alternate, Lily (Kunis), personifies the more erotic and devious Black Swan. In the ballet, both roles are traditionally performed by the same character, adding the demand of immense emotional range to an already physically and psychologically taxing art.

Aronofsky was also inspired by folklore surrounding doppelgängers; Nina and Lily resemble each other. Like the characters in "Requiem for a Dream," Nina's psychological state and grip on reality also deteriorate in a rapid and surreal manner as she goes to war with both her rival and her own inner demons.

The Virgin Suicides

"The Virgin Suicides" is Sofia Coppola's stylish adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides' 2003 novel. Despite its daunting title, it appears at first to be an idyllic romp in the suburban Midwest. Simmering underneath this white-picket-fence exterior, however, is a sense of deep psychological unrest. Much like the characters in "Requiem for a Dream" rationalize increasingly dire conditions, the five sisters at the center of Sofia Coppola's "The Virgin Suicides" put on the appearance of stability and flit through the oblivious gazes of those closest to them as their mental states deteriorate.

However, whereas the mother in "Requiem" is somewhat ditzy and involved in her own issues (though she still cares deeply for her son), the parents in "The Virgin Suicides" are much harsher: After the youngest of five affluent sisters attempts suicide, their parents put all of them on strict lockdown and oversee every aspect of their lives in isolation. This only serves to worsen their collective psychological condition. Ultimately, they fare no better than the estranged youths of "Requiem for a Dream," even if the road to their unfortunate fate appears more innocent.

Taxi Driver

If you ever need to make a case for getting a good night's sleep, "Taxi Driver" should be your Exhibit A. The plot of this movie probably never would have transpired if Travis Bickle had worked the day shift. But because his insomnia prompts him to start working as a nighttime taxi driver (in between trips to pornographic theaters), Bickle rapidly devolves into a very unique brand of existential crisis.

From fixation to fixation, delusion to delusion, he meanders the streets of New York City while attempting to cope with his PTSD as a Vietnam War vet and his moral panic in the face of what he views as the city's debauchery. In response, he molds himself into what he sees as an avenging angel for society, but in reality, he's going insane.

In fact, Bickle's dizzying spiral may be one of the best depictions of losing one's mind ever depicted on film. Like the characters in "Requiem for a Dream," the taxi driver is trapped in a hell of his own making when all he was really trying to do was feel better. As viewers, we are put in a strange cognitive position by each of these films: We can see where a character is coming from and sympathize, but we can also see where they're going and wish they would slam on the brakes.

A descent into madness is a common theme in the work of screenwriter Paul Schrader, who also wrote "First Reformed," "Bringing Out the Dead," "Obsession," and a variety of other psychological thrillers or dramas. Anyone looking for a gutting examination of the human psyche would do well to check out his filmography.

Being John Malkovich

Have you ever wondered if stars are just like us? Well, there's one way to find out: Take a grimy tunnel ride into their mind and literally look at life through their eyes. If you work between the 7th and 8th floor in the Mertin-Flemmer building in "Being John Malkovich," you can open one secret door and find yourself thrust into the consciousness of an actor. You can escape your sorry life for a day.

Drugs don't take center stage in this film as they do in "Requiem for a Dream" and some of the other films on this list. But in reality, the "drug" in this story is revealed in the title of the film itself, and made even clearer as we watch character after character become addicted to being John Malkovich. Like many brands of escapism both physical and psychological, the dependence that this experience nurtures takes its toll on the relationships and lives of those who misuse it.

Unlike other options on this list, this playful Spike Jonze-Charlie Kaufman collaboration offers plenty of hilarity in addition to astute psychological observations. Bonus points for the typically glamorous Cameron Diaz's surprising turn as a frump.

Eyes Wide Shut

In his final film, Stanley Kubrick pulled out all the stops. Not that he doesn't do that in his other works, like the notoriously disturbing "The Clockwork Orange" or "Full Metal Jacket," which could also belong on this list. But the particular brand of emotional distress in "Eyes Wide Shut" is a much more intimate slow burn.

After Alice (Nicole Kidman) confesses that she once seriously considered having an affair, her husband, Dr. Bill Harford (Tom Cruise) wanders the streets of New York in a series of increasingly foreboding misadventures. Kubrick constructs what feels like an alternate universe around him and his inner struggles, composed of little vignettes that are in turns erotic, mysterious, and deadly.

As Bill explores corners of NYC yet undiscovered, he stumbles upon all kinds of secrets and conspiracies. But these revelations pale in comparison to — and honestly, seem to exist only to facilitate — the slow illumination of his own mental state.

Whereas "Requiem" uncompromisingly showcases the consequences and casualties of its characters' selfish decisions, "Eyes Wide Shut" takes a more abstract approach: The misfortunes that befall those around Bill are not the concrete collateral damage of his journey, but simply elements that further his elaborate fantasy as he doubts his identity and marriage. That makes for an equally memorable and weird movie.

The Killing of a Sacred Deer

It's not a hunting movie — at least not in the traditional sense — but there's definitely a predator-prey dynamic at play in "The Killing of a Sacred Deer." Though it's eventually revealed that lives are at stake, the threat at first appears to be purely psychological. A surgeon (Colin Farrell) takes a young boy under his wing out of guilt due to a grim connection from their past. While the doctor insists on keeping this friendship secret at first, eventually he introduces the boy to his family — who begin to fall ill without explanation.

This is just the beginning of the strange things that happen in this movie. The dynamic between the boy and the surgeon, and between the surgeon and his family, escalate in ways you never would have dreamed of when you first pressed play. But even as the dread mounts, every beat is played and shot with a colorless sense of despair, as if everyone is already resigned to a miserable fate.

The heart of "The Killing of a Sacred Deer" is this slow and horrific realization that there's no way to stop an appalling series of events from unfolding — possibly because it's based on a Greek myth whose conclusion was written ages ago. Director Yorgos Lanthimos is no slouch in the dark drama department, having also made "Dogtooth," "The Lobster," and "The Favourite."

Trainspotting

Although it takes itself less seriously than "Requiem for a Dream," Danny Boyle's 1996 film "Trainspotting" similarly explores drug addiction from a devolving psychological perspective.

As is the case with the characters in "Requiem," the misfortunes that befall the group of friends in Boyle's film are largely a result of their individual choices — though these choices themselves are painted realistically as the social byproducts of addiction and poverty, which are explored in raw and uncompromising detail. While it begins as a comedic, rough-edged romp, the characters eventually endure some of the worst adversities ever committed to film, including a memorably horrific detox hallucination.

Aside from their similarities on a thematic level (revolving around addiction, relationships, societal problems, and the nature of reality), "Trainspotting" and "Requiem" share a foundational trait: Honesty. The brutality of the lives they depict is relieved only by a peppering of legendary trippy sequences that lower the thinnest veil between the viewer and the two films' disturbing realities.

Jacob's Ladder

Many psychological dramas have the unique ability to showcase real-world problems in intimate, if exaggerated, detail. Others focus on the abstract instead, exploring everything from spirituality to delusion through as bizarre a lens as they please. Occasionally, a psychological drama does both — and in the case of "Jacob's Ladder," the result is an atmosphere unparalleled in its unease and creepiness.

The film follows Jacob Singer (Tim Robbins), a soldier serving in the Vietnam War who's discharged back to his native Brooklyn. Unfortunately, home is no relief for Jacob, who must grapple with an old personal tragedy, PTSD, and a horrific government conspiracy that may or may not be real. The twist ending doesn't make the story any cheerier. It's no surprise that the movie grapples with heavy subject matter, considering that its screenwriter's main inspiration was the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

Disturbing and visually intense, "Jacob's Ladder" never crosses the line into schlock or pulp thanks partly to Robbins' convincing performance, which lends poignancy and vulnerability to his character.

Enemy

No one knows you better than you know yourself, but this can be a blessing or a curse. When the two main characters in "Enemy," both played by Jake Gyllenhaal, discover that they are carbon copies of each other, each of them uses this bizarre situation for his own unique ends.

In fact, the reaction each has to discovering his doppelgänger might be the only differentiating characteristic between the two men. While they appear physically identical, their psyches operate in diametrically opposed ways: a milquetoast but relatively moral man on one hand; a more sadistic, selfish man on the other. This creates a unique sense of conflict that drives the film as each becomes obsessed with his counterpart, whether due to fear or envy.

All this would be surreal enough, but then there's the psychological evolution each man goes through to become more and more entangled in each other's lives — even to the point where they share the same bizarre dreams that begin to bleed into reality. Like the complexities of "Requiem for a Dream," this entanglement threatens to be deadly to unravel. We humbly suggest a double feature with "Nightcrawler," another dark Gyllenhaal thriller.

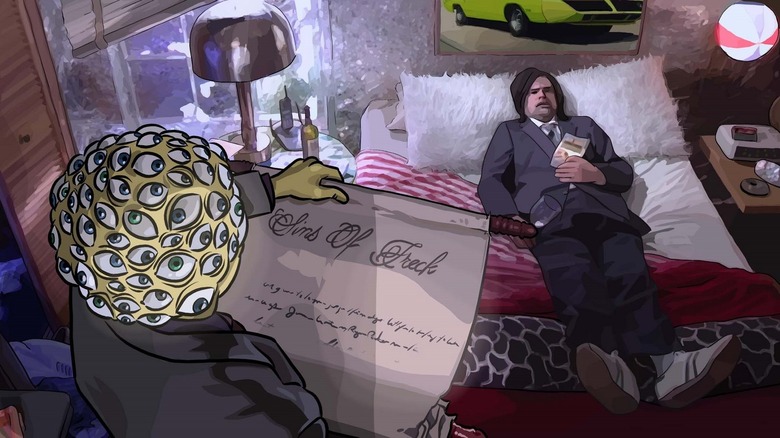

A Scanner Darkly

Richard Linklater's adaptation of Philip K. Dick's 1977 novel "A Scanner Darkly" echoes the paranoid, deteriorating mood of "Requiem for a Dream." It also centers around many of the same themes: Though "A Scanner Darkly" is a science-fiction film set in the future, drug addiction, social structures, and unstable relationships still take center stage.

The film is animated through a technique called rotoscoping, which involves drawing over live-action footage. Because of this, even though the film is animated, you can easily make out the faces of its illustrious cast: Woody Harrelson, Keanu Reeves, Robert Downey, Jr., and Winona Ryder, to name a few.

All of their characters are friends. Well, sort of — they're all addicted to Substance D, like much of the population, and are pretty paranoid of each other, engaging in regular acts of betrayal to serve their own interests (be they addiction, undercover drug-busting work, or, in the case of Reeves' character, both). But the results of each of their actions are more far-reaching than any of them know.

Antichrist

It's billed as a horror film, but Lars von Trier's "Antichrist" has few hallmarks of horror in the traditional sense. Every ghastly development in the film arguably has roots in the characters' own guilt-ravaged minds, not in the designs of some malicious supernatural force, but you could interpret the film either way. The ambiguity is what lends it its unassailable, disquieting power.

Fittingly, "Antichrist" kicked off Lars von Trier's unofficial "Depression Trilogy," a series of works said to represent the filmmaker's own mental health struggles. "Antichrist" is joined in this ensemble by the equally inviting titles "Melancholia" and "Nymphomaniac." The entire collection is worth watching, particularly the deeply unsettling "Melancholia," but "Antichrist" earns its spot on this list through sheer intensity. There are only two central characters: a husband (Willem DaFoe) and wife (Charlotte Gainsbourg) who retreat to a cabin to attempt to work through their grief after the death of their child.

If you're an avid fan of "Requiem for a Dream," there's a good chance you're drawn to "messed up" movies. If so, "Antichrist" is a must-watch: When it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, it caused perhaps the most varied reactions in the history of the event: Some people laughed, some applauded, some walked out, and four fainted. Which camp will you fall into?

Mother!

The polarized response to "mother!" (which director Aronofsky intentionally styled in lowercase) is like candy for people who like their psychological dramas to make them uncomfortable. "Requiem for a Dream" is gut-wrenching, but "mother!" is something else entirely.

You're uncomfortable the whole time, but you're not really sure why — and when everything finally hits the fan in deranged fashion in the last 20 minutes or so of the film, it seems less the result of a coherent sequence of events and more like a violent fever dream you wouldn't even try to explain when you woke up.

But if you were to try to explain "mother!" you would probably talk about the strange relationship between Jennifer Lawrence's "mother" and her husband, known only as "Him": the former is the muse for the latter, a poet. They live together in peaceful solitude until the arrival of an impolite and eccentric couple — intense fans of the poet's work — upends their tranquil existence. But that's only the beginning. If you liked the unforgiving gruesomeness of "Requiem for a Dream," you'll love to hate where "mother!" ends up.

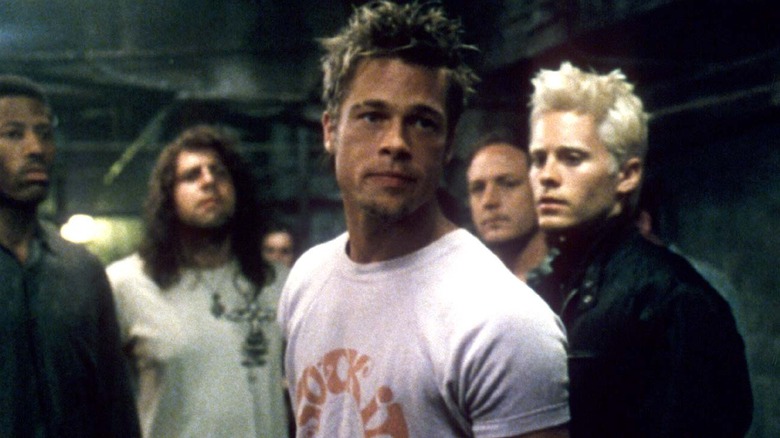

Fight Club

You knew we had to talk about "Fight Club." For a genre of film that seems to repeatedly demonstrate the dangers of not getting enough sleep, psychological dramas sure ten to keep viewers up at night with their bizarre premises. The main character of "Fight Club," an unnamed Narrator, is an insomniac much like Travis Bickle.

The Narrator holds a low opinion of society and is deeply dissatisfied with his place in it until he meets (or invents?) his volatile character foil, Tyler Durden, and establishes a fight club to air his pent-up aggression. Like the characters in Aronofsky's "Requiem for a Dream," the Narrator makes frequent attempts at escapism and demonstrates himself to be deceptive and unreliable along the way.

In "Requiem," the consequences of these personal tendencies are plainly spelled out. But we don't see the extent of the Narrator's deception — including self-deception — until the very end of "Fight Club," when the film's notorious twist reveals that the narrator is, perhaps more than any other individual in any of these films, very much imprisoned in a hell of his own making. Based on Chuck Palahniuk's novel of the same name, the movie is mordantly funny and hyper-stylized in a way that tends to attract edgy adolescent fans. Still, this cult classic offers a compelling psychological spectacle.