The Most Misunderstood Movie Lines In History

A number of quotes in our cultural lexicon have come from the rich landscape that is cinematic history. From "Use the Force, Luke" to "I'm gonna make him an offer he can't refuse," "You had me at hello" to "I've a feeling we're not in Kansas anymore," the greatest quotes in cinema history take us back to the often wonderful scenes they're in. At the same time, as quotes get passed along, there's always the possibility of misunderstanding these linguistic artifacts of cinema.

Sometimes the misunderstanding is as small as a misheard phrase or a misunderstood word, but other times a misunderstanding can cause a dramatic misinterpretation of a pivotal scene, confuse its ending, or miss emotional context that's loaded with meaning — but only if you understand it. These misunderstandings span every genre, from comedies like "Groundhog Day" to action films like "The Fast and the Furious," fantasies like "Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone" to dramas like "Wall Street." What follows is a list of the most misunderstood movie lines in history, from early classics like "Citizen Kane" to recent sci-fi phenoms like "Tenet," and many of these lines will make you never see the film the same way again.

In Wall Street, Gordon Gekko thinks greed is more than good

1987's "Wall Street" follows junior stockbroker Bud Fox, an up-and-coming professional who admires Wall Street tycoon Gordon Gekko. Fox gets Gekko's attention through the promise of insider trading, but as he ventures deeper into Wall Street his decisions start to have ever more dangerous consequences, and these cause him to seriously reevaluate his actions. It's a blunt and critical exhibition of the greed of 1980's capitalism, and a great film in its own right (Michael Douglas won the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1988 for his portrayal of the greedy Gekko).

Beyond its overall notability, the film is also famous for a quote that's often thematically misunderstood. In a key scene, Gekko famously defends greed, saying "the point is, ladies and gentlemen, that greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right, greed works."

Co-writer Stanley Weiser has lamented the number of times executives have thanked him because of the influence Gordon Gekko's greed has had on them. In a 2008 LA TImes editorial, Weiser pushed back against the co-opting of the line, usually sans context.

"Thinking back upon writing the screenplay of 'Wall Street,' I never could have imagined that this persona and his battle cry would become part of the public consciousness," Weiser wrote. "And that the core message of 'Wall Street' — remember, he goes to jail in the end — would be so misunderstood by so many."

Quoting "Wall Street" filmmaker Oliver Stone, he said that "greed is a bummer" and those who admire Gekko do so "for the wrong reasons."

Dom absolutely does not live his life a quarter mile at a time

In "The Fast and the Furious," Dom uttered the now well-known quote "I live my life a quarter mile at a time." It makes sense at face value — after all, he's a street racer. Dom proceeds to discuss how "nothing else matters. For those 10 seconds or less, I'm free," free of worries, of the team's issues, and the like.

Sure, it's a quotable phrase, but the odd thing is taking it at face value is a fundamental misunderstanding of the film and the whole series. On one level, that may be how he functions as a street racer in the first film. As the series progresses, however, that is absolutely not how he lives his life.

Through the succession of films we see Dom race some here and there, but beyond that his activities include everything from criminal endeavors to combatting dangerous organizations to working with Luke Hobbs and the forces of law and order. More important, however, is his evolution into someone who cares about family over anything. The series is so much about family, in fact, that it has inspired a wave of memes around the 9th film.

In essence, taking that quote as Dom's philosophy disregards any growth he has made in the films since.

Groundhog Day is a crash course in Buddhism

In "Groundhog Day," a weatherman (Bill Murray) travels to Punxsutawney for its annual Groundhog Day festivities. He's a cynical jerk who overestimates his own importance, and his life is turned upside-down when he ends up in a time loop, repeating the same day over and over again an impossible number of times. In the process, he discovers much about himself, learns to be selfless, and falls in love with his producer Rita (Andie MacDowell).

It's a charming film, and when the day stops repeating Phil describes the moment as "the end of a very long day." Beyond the literal truth of the line that his "very long day" is over, the line also signals a deeper meaning of the film that is often misinterpreted. "Groundhog Day" isn't only about becoming a good person, it's essentially a Buddhist-proximate film about becoming a good person through staying in the present.

Director Harold Ramis never claimed to be Buddhist, but when his college roommate and best friend became a Zen priest it resulted in Ramis researching Buddhism, and his wife and her mother had heavy Buddhist backgrounds as well. While Ramis never directly intended the film to be intentionally Buddhist, he acknowledged that various subplots do reflect Buddhist values and leanings. Critics and analysts have praised the film for representing the Bodhisattva path as well as the Buddhist teachings on samsara, the cycle of rebirth that Buddhists consider to be a type of suffering.

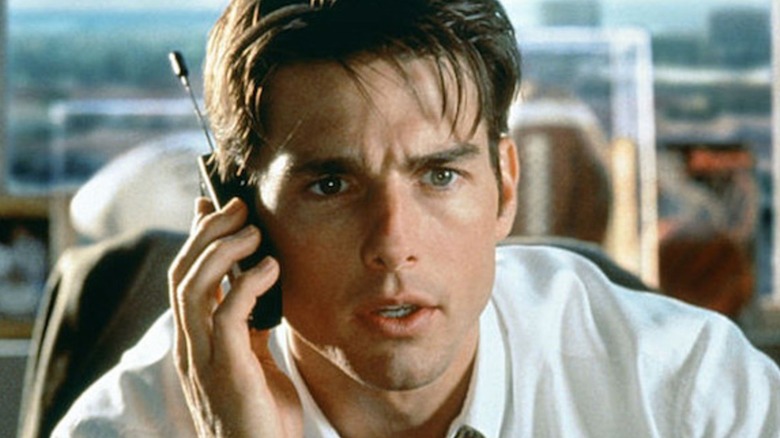

That 'romantic' line from Jerry Maguire proves no one should have you at hello

The 1996 Cameron Crowe romantic sports dramedy "Jerry Maguire" stars Tom Cruise as a sports agent who, after an epiphany, drops out of his company and attempts to start a new career as a more thoughtful, dedicated agent. When he leaves, the only person who will stand with him is Renée Zellweger's Dorothy Boyd, and over time we see him break it off with his fiancée and eventually get in a relationship with, and marry, Dorothy.

As time passes that relationship fails, but after some professional successes Jerry finally realizes what Dorothy means to him and vows to recommit to making it work with the line "I love you. You complete me," to which Dorothy responds with the now iconic line "you had me at hello" (his first word upon entering the scene).

The line is often taken to be a romantic line in a romantic scene, but at this point Dorothy was literally just saying in a Divorced Women's Group that she knows she should be independent of needing men but she can't stop herself. She says "Women need to stick together, and not depend on the affections of a man to 'fix' their lives. Maybe you're all correct. Men are the enemy. But I love the enemy."

After having been routinely neglected and mistreated by Tom Cruise's character, she has no real reason to reunite with him. If anything her instincts are correct.

By saying "you had me at hello," Zellweger's character is saying that his apology is unnecessary, that Jerry's mere presence is enough. When you look at it through that prism the quote seems less romantic than myopic.

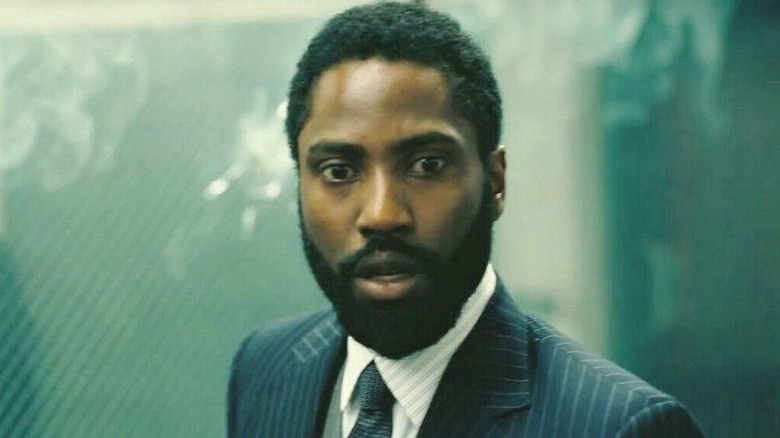

The Tenet free will explanation isn't what it looks like

In Christopher Nolan's twisty, complex sci-fi thriller "Tenet," an unnamed "Protagonist" is set on the journey to stop a villain named Sator, who is in contact with a mysterious future organization. Sator wants to set off a doomsday device that will reverse the entropy of Earth all together, a process known as inversion. When inverted, objects or people are in effect temporally reversed, causing them to run backwards in contradiction to our ordinary temporal experience. The motivation of this organization is that future catastrophe has endangered future Earth life, so the future wants entropy inverted so they can invade the present.

As the Protagonist is inquiring about the inversion process he asks if we still have free will, which is explained away quickly in the line "that bullet wouldn't have moved if you hadn't put your hand there. Either way we run the tape, you made it happen." A few lines earlier, she also explains he would have to have dropped it.

But none of this makes sense as a defense of free will. If a future version of an individual undertakes a decision that forces their present self (relative to that version's perception) into a chosen path, there's no ability to change that pre-determined path. Fellow agent Neil even says as much when the Protagonist asks "can we change things? If we do it differently...?" to which Neil replies "What's happened's happened." If will is pre-determined (or post-determined) by the future, it still isn't free.

Willy Wonka's snozzberries line is a perverted joke

1971's "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory" is based on characters from British author Roald Dahl's 1964 novel "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory." In the film, we see Wonka (Gene Wilder) demonstrate "lickable wallpaper" for nurseries, covered in fruit that tastes real. Banana, pineapple, a whole array of fruit adorn the sample wall. Wonka urges: "Try some more! The strawberries taste like strawberries. The snozzberries taste like snozzberries!" Most take the line to be a funny-sounding word in a children's-oriented story — almost Seussian wordplay — but the troubling thing for a kid's film is that the word "snozzberry" were revealed in Dahl's later works to be his own original slang ... for penis.

In his 1979 novel "My Uncle Oswald," published for adults, he follows Oswald Hendryks Cornelius who in the novel is the "greatest fornicator of all time." When his accomplice Yasmin Howcomely is asked how she controlled George Bernard Shaw, she commented "There's only one way when they get violent ... I grabbed hold of his snozzberry and hung onto it like grim death and gave it a twist or two to make him hold still." In other words, Dahl retcons snozzberry to be slang for male genitalia — a realization that dramatically dirties our interpretation of the classic Wonka line.

Silence of the Lambs' "fava beans" line is a soft brag about being med-free

In Jonathan Demme's 1991 classic "The Silence of the Lambs," an FBI trainee is assigned to the Bureau's Behavioral Science Unit to talk with Hannibal Lecter, a cannibalistic serial killer and former psychiatrist. Another serial killer is on the loose, Jame "Buffalo Bill" Gumb, and the Bureau hopes to use Lecter's unique qualifications to inform their investigation. In the film's most famous exchange, Hannibal tells Clarice "a census-taker once tried to test me. I ate his liver with some fava beans and a nice Chianti." It's a good line that's often read as Hannibal attempting to intimidate Clarice, and that's likely true to some degree. At the same time, its hidden meaning is a stealth medical joke suggesting Hannibal is off his medication.

A common treatment for patients like Hannibal would likely be monoamine oxidase inhibitors, also known as MAOIs. Funny enough, the three things you shouldn't consume on MAOIs are liver, beans, and wine ... a fact that a psychiatrist like Hannibal would know. That combination would potentially prove fatal, so the specifics of that joke could well be Hannibal stealth-bragging that he's off his medication, a joke that went over Clarice's head ... and ours.

The "Rosebud" whisper in Citizen Kane was another layer of insult against Hearst

The much-lauded "Citizen Kane" begins with the death of media magnate Charles Foster Kane, whose final word is "Rosebud." A newsreel producer charges a reporter with the task of getting to the bottom of the mysterious word — what was Rosebud, and why did Charles Foster Kane say it on his death bed? Eventually, the film reveals that Rosebud was a childhood sled that Kane treasured as a boy, with the invocation of the word implied to be his desire to return to that carefree youth. The use of that particular name, however, makes it possible that "Rosebud" has another layer of meaning entirely, one that represents yet another dig against real life media magnate Randolph William Hearst.

It's widely held that the character of Charles Foster Kane was inspired by media magnate Randolph William Hearst, an influence that was denied in public but which was considered fairly obvious in its day. Hearst tried to silence the film entirely, as many personal details about himself and mistress Marion Davies were inserted by writer Herman Mankiewicz, all detailed in the 2020 Netflix Oscar nominee "Mank."

According to the book "Citizen Welles," in the 1970s the story emerged that "Rosebud" was Hearst's nickname for Davies' genitalia. This was furthered by writer Gore Vidal, who laid out his case in a must-read reply to a letter from a lawyer who questioned his assertion by essentially saying Davies had confirmed the tidbit through a mutual friend. According to Vidal, Mankiewicz may have come across the nickname during drunken encounters with Davies and, better yet, may have even inserted it into the script with Welles none-the-wiser. Of course this is all difficult to verify for certain, but it quite possibly adds an entirely different, twisted, personal joke at the heart of one of the most influential films in history.

Behind Get Out's positive final line is an sad undercurrent of cynical conspiracy

Jordan Peele's masterful "Get Out" followed Black photographer Chris Washington's visit with girlfriend Rose Armitage's family. To his horror, he discovers that the entire family is part of a wealthy white cult (called Order of the Coagula) who transplant their minds into the bodies of various Black people ... and Rose is among the scouts that brings the group victims. Chris is captured, but manages to fight his way out of their lair, where he escapes to find himself saved by his friend Rod. With Rod driving him away from the treacherous mansion, the last line of the film is Rod saying "Consider this situation f***ing handled", but Chris doesn't respond.

While the movie's theatrical release ends on a largely positive note, giving that line a positive connotation, the film's ending is dour from Chris' perspective. Chris knows that the majority of the wealthy, connected Order of Coagula are still active. He may have escaped (albeit with betrayal, shock, and likely trauma), but he surely knows that this insidious villainy is not handled. This puts a much darker connotation to that end line, cynical undertones which are more overt in the much darker Alternative Ending that ends with Chris in jail for killing the Armitage family.

Snapes first line to Harry Potter is both a potion quiz, and a deep emotional admission

In J.K. Rowling's first novel and film in the Harry Potter series, "Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone" ("Sorcerer's Stone" in the U.S. and India), Severus Snape's first interaction with Harry Potter has him chiding the "famous" Potter for failing to pay attention. In response, Snape gives the young Potter a pop quiz: "Tell me, what would I get if I added powdered root of asphodel to an infusion of wormwood?" In its immediate context, it seems like Snape calling attention to Potter for failing to pay attention by asking him about a random ingredient combination. In reality, it's a deeply hidden admission of sadness and guilt over the death of Potter's mother (whom he loved).

To understand the line, it's important to note that throughout world history significant cultural meaning has been given to flower types and arrangements, like how roses are said to symbolize love. Interest in floriography (the "language of flowers") became popular to many in Victorian England and the U.S., leading to something like asphodel becoming a symbol of death and the afterlife since Ancient Greece, while its meaning in Victorian floriography came to be something akin to "remembrance of one who has passed" or "my regrets follow you to the grave." Wormwood, meanwhile, represents "absence," "regret," or "bitterness."

Thus, Snape is indeed quizzing the young Potter on a potion (incidentally those are the first ingredients of the Draught of the Living Death), but the subtext is an expression of his remorse and sadness over Harry's mother's death upon his first interaction with her son.