The Ending Of The Witcher: Nightmare Of The Wolf Explained

Contains spoilers for "Nightmare of the Wolf"

Fans eagerly awaiting the December 17 release of Netflix's "The Witcher: Season 2" can now get their monsters, mages, and magic fix in the form of director Kwang Il Han's animated spin-off film, "The Witcher: Nightmare of the Wolf." The prequel focuses on the backstory of Vesemir — Geralt of Rivia's (Henry Cavill) mentor and father figure, played by Kim Bodnia in Season 2 — and chronicles the events that led him to become a witcher as well as those that forced him to rethink his beliefs, priorities, and values.

Since it's exactly those beliefs, priorities, and values around which Geralt's character will ultimately form, the film serves to bridge the gap between the Geralt known to fans of Season 1 and the Geralt created over the course of the series' source material: the six novels written by Andrzej Sapkowski. Although "The Witcher: Nightmare of the Wolf" is not, strictly speaking, a depiction of anything from the novels (or the short stories from which they were compiled), the film's writer, Beau DeMayo, was intent on creating something that worked within the canon and franchise.

Nightmare of the Wolf explores previously untapped stories

In an interview with CBR, DeMayo discussed the challenge of delving into storylines the books don't necessarily investigate, while simultaneously staying true to the characters and narrative that they do: "I started thinking about who was Vesemir at the start of his career," he explained, "before the horrible things that happened with the witchers in the canon." In exploring these untapped arcs and focusing on "that unanswerable mystery in the 'Witcher,'" DeMayo and Il Han touch on a number of themes integral to Sapkowski's original works, and help give fans a deeper understanding of the dynamics of both The Continent and the various factions within it.

It's difficult not to read Sapkowski's original saga as a commentary on (or, at the very least, a world inspired by) the tumultuous and war-torn history of his home country of Poland. And yet, the sobering timelessness and universality of the darker aspects of human behavior explored in the novels gives them an endless capacity for application and interpretation. "The Witcher: Nightmare of the Wolf" foregrounds these aspects, deliberately and apparently constructing its main narrative around themes such as class and racial divide, societal constructs (aka illusions), and the symbiotic relationship between fear and violence, ignorance and hate.

Classism plays a key role in Nightmare of the Wolf

When we first meet DeMayo's Vesemir (Theo James), he's a young, virile, witcher equivalent of a "bro-dude," focused mainly on collecting coin and living it up when he can. (Right down to the haircut and facial hair, there is something unmistakably "G.T.L." about this bad boy beast slayer.) But the hunky hexer's laissez-faire attitude and shameless overconfidence belie a deep-seeded desire to rise above the impoverished social status into which he was born, and — by becoming a witcher — ostensibly escaped.

Flashbacks to Vesemir's childhood reveal that he was born into servitude, and longed for nothing more than to free himself, and his childhood love Illyana, from the shackles of their station. Although, at the beginning of his narrative, we're shown a Vesemir who still harbors hatred for the nobility he so envies, by the end of "Nightmare of the Wolf," he's determined to live for something more meaningful than glory, coin, and status.

The same young girl he once abandoned in hopes of making something of himself (in his mind, for her) sees her own fair share of classism, even as she rises through the ranks of society. In Vesemir's absence, Illyana (Mary McDonnell) marries the son of the noble family that claims her, and upon his death, inherits his title: Advisor to the King. It soon becomes clear, however, that even as Lady Zerbst, she has difficulty commanding the respect her position should, by right, demand. Though her late husband clearly saw her as an equal, the nobility and their ilk never will. Had they seen her as anything more than a servant — had they been able to see the common wisdom behind her reasons for peace — the violent war between the townspeople-Tetra and the witchers at Kaer Morhen would never have broken out.

In the end, it's Illyana's untimely death that finally forces Vesemir to confront the misguidedness of his priorities.

Monsters to kill monsters

Those priorities (coin and glory) are shared and reinforced by his own mentor — and champion of the moral gray-area — Deglan (Graham McTavish). When Vesemir tells the frightened, abandoned orphans at Kaer Morhen (the next generation of witchers) that they'll gain "strength, purpose, (and) respect," he's merely parroting what he was told by Deglan as a child. The need for this kind of purpose and place in life (which stems from being born a "nothing," or worse, "different") is exactly what drives Deglan to engage in the mutagenic alchemy for which the witchers are ultimately condemned, and nearly wiped out. "Monsters were going extinct," he tells Vesemir. "I had to protect our way of life." Deglan feels forced to create new monsters because it's only mankind's reliance on the witchers — for protection from the "scarier beasts" — that keeps them from turning on and hunting down witchers. Now, they finally have turned on the witchers, with a little push from the witcher-hating mage Tetra Gilcrest (Lara Pulver).

Though Illyana doesn't agree with Deglan's approach, she does tell Vesemir that war was inevitable. "Because you're different," she says, "and killing is easier than tolerating."

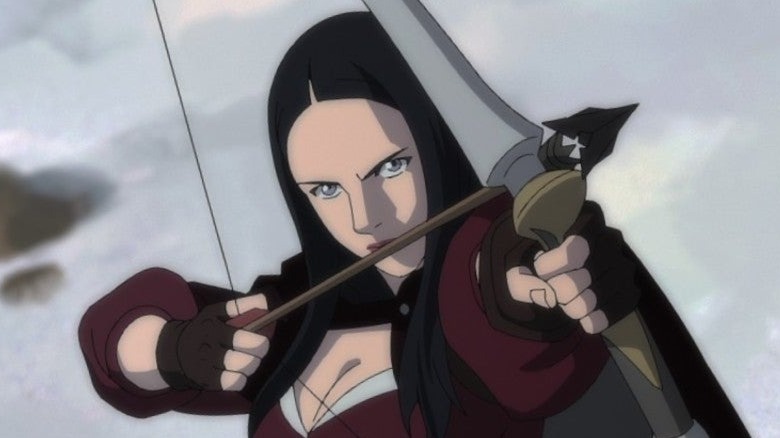

It's no accident we're immediately treated to a visual of the fear-mongering puppeteer, Tetra, preparing for battle. On the surface, she's the most outspoken racist in "Nightmare of the Wolf." Tetra even goes so far as to publish propaganda pamphlets denouncing witchers — whom she views as corrupt mutations, in contrast to her "pure" mage lineage — as "rogues without virtue."

In the end, we learn there's more to Tetra's hateful conviction than meets the eye. Her fervent hatred of witchers stems from her experience with a single witcher, an extremist who tricked a priest into believing that Tetra's mother was possessing him. The witcher killed the young mage's mother in front of her eyes, then split his cut of the coin with the accomplice he used to turn the gullible priest's fear and ignorance into a paycheck. In the same way that Vesemir's experience with one particular nobleman as a child colored his understanding of the world from there on out, Tetra's traumatic experience — with a radical, rogue witcher — in turn radicalized her.

Ignorance and illusions

"The Witcher: Nightmare of the Wolf" thus highlights the interconnected, cyclical nature of a litany of society's most self-destructive impulses: ignorance begets fear, fear begets hate, hate begets violence, violence begets divides in class and race, divides in class and race beget ignorance, and so on, and so on. In the end, only Illyana seems capable of breaking the cycle, when she asks Vesemir to forgive the tragically mutated Kitsu for her murder. "She didn't ask for this," she reminds him. It's a gesture that exposes the narrative of Kitsu-as-monster for the lie that it is.

DeMayo repeatedly explores the idea of illusion — both magical (for our purposes, "literal") and metaphorical — to reiterate what the film and the IP as a whole have to say about our darkest instincts and motivations. For most of his life, Vesemir is motivated by the illusion of wealth and status. Though, as a witcher, he obtains both, it's a superficial victory, and one that doesn't ultimately bring him happiness. Moreover, in the end, it's a literal illusion (a spell cast by the mutant hybrid Kitsu) that causes him to kill the only woman he ever loved. (The same woman, it's worth noting, that he left behind in pursuit of — you guessed it — an illusion.)

Although it's Vesemir who falls victim to the most devastating illusion of all, it's Tetra who delivers the film's message to viewers. "It made food tastier," she tells Vesemir of the mages' practice of casting illusions around undesirable foods, before going on to explain that the telltale sign of an illusion is its aftertaste: "bitter."

There'll always be another monster

There's more than a little irony embedded in the reaction that some fans had to "The Witcher" Season 1 creators' decision not to use race, or even gender, as a basis for casting canonical characters. When showrunner Lauren Hissrich was criticized for altering the (arguably, only ever implied) race of various characters, she had this to say on Twitter: "The Witcher is REALLY interesting when it comes to depicting racism because it's about species, not skin color. What makes characters 'other' is the shape of their ears, height, etc. In the books, no one pays attention to skin color. In the series... no one does either. Period."

In an instance of life imitating art imitating life, supposed die-hard fans of Sapkowski's work (or, purists) directly embodied and made incarnate one of the saga's main allegorical endeavors. Whether or not the casting backlash was on the minds of Kwang Il Han and Beau DeMayo when they developed their spin-off doesn't ultimately matter, because "Nightmare of the Wolf" is so relentlessly unsubtle in its exposition of the cyclical mechanics of racism and hate that it can't help but be in conversation with what came before.

If "The Witcher: Season 1" introduced audiences to the dynamics of the story's key players, then "The Witcher: Nightmare of the Wolf" introduced them to a deeper understanding of the dynamics of The Continent and its history. (And, in doing so, the latter opened the door for "The Witcher: Season 2" to answer some of the philosophical questions it poses.)

Although we don't discover which of the Kaer Morhen orphans is the young White Wolf until the last scene, the impact the events of the story have on his future mentor give audiences a more thorough understanding of the upbringing that created the hero at the heart of the Netflix series. "They hate us," an unnamed orphan tells Vesemir, to which the now last-surviving grown witcher replies, "There'll always be another monster ... Geralt."