Lisa Joy Reveals Why Hugh Jackman Was Right For Reminiscence And More - Exclusive Interview

HBO's "Westworld" series often plays a game of bait and switch with its audience, presenting viewers with a reality filtered through the perception and memories of the characters within the story. However, in many cases, we discover that these characters are actually robots whose programming often makes them unreliable narrators.

Lisa Joy, who writes and executive produces "Westworld," takes a similar — but often opposing — tactic with her feature writing and directorial debut "Reminiscence." Much like "Westworld," the Hugh Jackman-led sci-fi story takes place in a nebulous future time marked by conflict between the haves and the have-nots. In the world of "Reminiscence," we see the consequences of climate change as the cities in the story are flooded, living under the threat of inevitable complete submersion.

In "Reminiscence" we meet Nick Bannister (Hugh Jackman), a man who provides a specific type of service — he can access and bring to life anyone's memories. For some, it's a source of escape; for others, it's an opportunity to solve criminal cases. And for Nick, it's an obsession to understand if Mae (Rebecca Ferguson), a woman he fell in love with, shared his feelings or was merely manipulating him. While Bannister struggles with his own memory, the audience is given a much more definitive sense of the reality in which Bannister lives.

Looper sat down with Lisa Joy to talk about who Nick Bannister represents, why she enjoys telling stories about perceptions of memory, and the challenges of getting an original story told in the studio system, especially as a female creative in the filmmaking industry. Spoilers for "Reminiscence" ahead!

Perception of memory: Reminiscence vs. Westworld

I wanted to ask about Nick Bannister as a character — in particular, this idea of someone who is struggling with perceptions of time and memory. Because it feels like this a story you like to tell, and I wonder what it is about that particular way of telling stories that appeals to you?

Well, for me, the conceit of memory and going back in memory just kind of dictates, in some way, the structure of the film. It's like we, as the audience, get to go down trips down memory lane along with our narrator and the eyes into the film, which is Nick Bannister. So I just went from there. Unlike in "Westworld," we play with time, but it's kind of cards down a bit more until the reveal. And in this, it was always cards up for me. When he comes out of the tank, you're with him and you know, "Oh, okay. That was a memory." And so for me, because of the format as a film, I was like, "Okay, well, we're just going to explore memory, but we'll do it hand-in-hand so each reveal announces itself and we can be there with the characters."

But in terms of the subjectivity bias that Bannister has, which I'm grateful to you for pointing out because it's funny, not a lot of men point this one out. And I'll tell you it's because when I first did the film, I knew it's very hard to make an original film. It's hard to make one that has action and noir or whatever the heck I was trying to do. I wasn't trying to do an arthouse film or a rom-com or whatever, and Hugh and his involvement in it is what made it come alive.

But what's even more remarkable about this is that before starting to write this, I talked about being pregnant and all that stuff, all the warm and fuzzy stuff, which is completely true and goes to the romantic ideas I have about memory. But I'd also just worked in a show where I was the only woman for two years and the conditions were so terrible that I had to leave in the end. I would rather be unemployed than carry on in that way. And I remember it slowly eating away at me, the idea that women can't write action and women can't be funny and women can't do this. And then on top of it, of course, the suppositions about intelligence and all the sex stuff.

And for me, writing always comes from a really personal place. And so I really struggled with that and I was really hurt by it. And I was really trying to find my way in the world when it felt like no matter what I tried to do, I couldn't just sell a story or write a thing. I had to take the gaze of a lot of expectations that had nothing to do with me and dance around it like Grace Kelly, where like, "All right. An action scene, but don't worry, a woman will cry somewhere." Like, what do I have to trade to be allowed to do those things?

And I was finally given, at that moment, the time to write something for myself fully dictated by me. And what I wanted to do was take one of the most old-fashioned, retro, male-driven genres — noir, also sci-fi is a bit like that — and Easter egg my actual thing that I was trying to explore, which is, as I told Hugh in our first meeting, I said, "People are going to think that you're the hero of this story, and that it's just that hero's arc, it's Wolverine in a suit."

And I'm like, "But what I need to know, and what I need you to know for your performance, is that if you do this movie, it's actually about your blindness, that this film is an indictment of the male gaze, and you're not the hero, and this love story isn't a pure, affirming, easy love. It is about how, even though you're a good guy and you can have some full platonic relationships with women, when you fall for this woman, you want to see something very specific and she knows it and she's playing with that too. Because as a woman, you have to understand how people are seeing you just to survive, just to walk down the street in safety." And so it was like Hugh was my confederate in being the movie star who said, "Okay, well, let's try to subtly dismantle the very idea of that male romantically."

Why Reminiscence ends the way it does

There's something you kind of locked in on for me, which is interesting: the ending where Bannister is locked in the past, and Thandiwe Newton's character, Watts, is able to carry on in the future. I'm curious as to how you arrived there and, based on Bannister not being a hero, if that was always the ending that you intended?

Yeah. That was always the ending for me. And I consider it to be a dual happy ending. The idea of Watts being able to surmount her demons and her shame and move forward, of course, that is a beautiful and classic arc, and she brings it to life with such warmth and humanity. And I wanted that because that's so important. That kind of stoicism is so important in life, to be able to pick yourself back up and just keep marching forward, especially if you're a woman.

And the idea of Bannister and Mae and what happens to them as being a happy ending, for me, it's like ... And this really struck me when I was talking to my mother-in-law during COVID. She was all alone, living in this little house for like two years and she's widowed. So she was really all alone and you can Zoom her as much as you want, but it's terrible. We would talk about memories and about things that we did together. And she would talk about my husband when he was a little boy.

And the idea that it's somehow lesser to go back in time and to live in a moment that was so cherished, for me, that's a scale that I don't attribute to time. To me, a more important moment in time isn't necessarily the most recent moment. The more true moment isn't necessarily the current moment. Things happen and we don't follow three-act structures. And sometimes the most meaningful moments in our life are in the past. And I don't think it's a betrayal of a character in any way to want to revisit them, especially if the alternative is prison.

But to be able to live in that happiness, I mean, I would wish it on a lot of people. I would wish it on a lot of people who are suffering, who are suffering with depression or loneliness or grief. Sometimes you just want to hit the off button just to survive that moment, and to go back into memory and remember the things that were beautiful and the things that you cherish. I think that's a completely lovely way to also have a happy ending.

How the cast changed Reminiscence for the better

I love that you had the ability to tell this story the way you wanted to, but there is a point when you have these actors that come and they're going to bring something that you did not originally intend and discover aspects of a character that you wouldn't have seen on your own. Here you have three incredible performers: what was it was that Hugh and Rebecca and Thandiwe realized about these characters and discovered about them while you were working together?

The thing that was incredible to me that Hugh did was, it's like when I told him about what I wanted to do under the surface of this, this indictment of the male gaze, that was the character he signed on to play. And you can see in his performances when he is holding back, when he is being fooled and allowing himself to be fooled. He allowed himself to be vulnerable in this incredible way. There is a scene in which he's looking for Mae and he was screaming, "Where is she?" And at first, it was very emotional. He was doing it in this incredibly emotional way, and it was heartbreaking to see and a beautiful performance. But for me, that's the performance that you have in a love story, and that's not what this moment was.

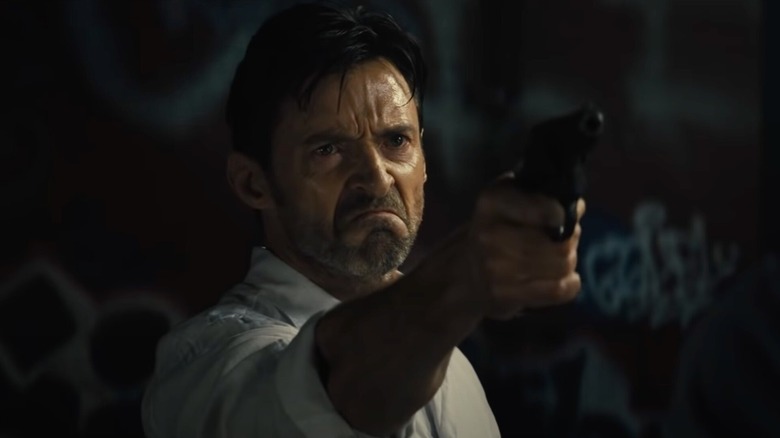

And I was like, "You know what? You are driven almost mad because your girlfriend disappeared, and now you're a dude wandering on with a gun, pointing at people. You're no longer the good guy. Just because you fell in love and they disappeared, doesn't mean that you're right. You've crossed a line here. And can you give me a take where you're ugly, where you've become the villain?" And that's exactly what he did. We did that take over and over again. And that kind of choice, that kind of openness to take a step back and let other people shine in that moment is a very generous thing that most movie stars wouldn't do.

Most movie stars would be like, "No, I want the classic hero's journey. I'm never going to be wrong, I'm going to knock everybody out, and I'm going to get the girl." And I had to be very honest with Hugh at the very beginning that, that isn't what my plan was and that, that's not what this movie was because there were many that could fill that for him. And so the thing that surprised me was how generous he was in going with that. And just the thing that ... Every person he interacted with on that set, Rebecca, Thandiwe, we would marvel at how generous he was in taking a step back a little bit and letting the women lead. It was incredible.

And so Rebecca, Rebecca brings a sharpness to her that I thought really dimensionalized that same game of cat-and-mouse that I was after. There would have been an easy way to play this character as simply winsome and broken and, "Oh, I have an addiction," or, "Oh, I'm lost and I'm sweet and please take care of me." And Rebecca, because she's nobody's fool and is a woman who has experienced life and has taken care of herself, defied that choice at every turn. And sometimes it would have been the safer choice. "Let's just have you cry and collapse in his arms for a second so people can see how vulnerable and likable you are," and she didn't want to do it. She wanted to show a woman who was lovable despite not pandering to that type of femininity. And frankly, it's a woman I recognize so much more than that winsome girl waiting to be saved. And so I think that's what she brought to it. She's all fire and smarts and sexiness. And we held hands and said, "Let's do this. Let's do it this way. Let's go for broke."

And then of course, Thandiwe, who is just ... I mean, she could be a silent movie actress in that her face is so expressive. The thing that she really brought to me too was ... I'd given most of the humorous lines to Watts because she's the one who's watching this, her friend get entirely brainwashed and turned around, and she's the voice of reason being like, "Hey, Hey, wait a second over here, buddy." And so she got to be caustically funny. But there are still moments in which her delivery was so funny that ... There's a moment when, later at the hospital, Hugh's character is confessing something to her and she's trying to warn him not to confess it, and the look on her face as she does it is so great.

And then afterwards, she ad-libbed "All right then," and just did it in such a way that was so fantastic. And I was like, "That's just great. That's surprised me and that was a new dimension to even ... It was meant to be funny, but she just nailed it. And that's hard to do, to do humor without breaking the character's positioning in that moment, which was a serious moment.

Filming an emotional action scene under water

I wanted to ask about the action sequence between Hugh and Cliff Curtis, where they're underwater and they're running and jumping around. There's serious emotionality in this scene, but it's also an action sequence, and I want you to talk about filming that in particular.

I loved filming that. So I just love filming action. And it's not often to ... You don't often get to do a noir, a smaller movie, on the kind of budget that I have and do action set pieces. So I tried to make room for them in the way that I organized the film. I knew I wouldn't be able to do wall-to-wall stuff. We couldn't afford any pre-vis or anything like that, but I knew that I could maybe get the kind of action scenes I wanted anyway by relying on the incredible fighting skills and performance skills of my actors. I didn't want to have to cut away. I wanted it to be as practical as possible and as real as possible.

And so the fight scene starts in a hallway. So that ending scene is this long fight, and I wanted to show the cadences of an actual fight. I love doing martial arts myself. And it's funny because you very seldom see people get winded and just start to suck at fighting in the middle after a long protracted fight. But the whole point I wanted to show was he's not a superman. He's not Wolverine. He's human. And there's a point where they fall down the stairs and are so winded, they just look like no one has it in them anymore to do any of this. And that's what I wanted.

So we cut it together. We choreographed the action to be pace like fast, fast, fast, slow, fast, fast, fast, slow. And in the slow is when I tried to reach for emotion because I wanted each fight scene to say something about the emotional development of the character. And so when it gets slow again, one point where it gets slow is that piano goes through the floor after it's all fast. Everybody's beating each other up. It's all well and good. And then the piano goes under the floorboards and the character's like, "Oh shit, now I got to save the guy I was trying to kill because he has something I need."

And of course, in the underwater sections, I wanted all that to be practical. And I wanted to get that sense, that claustrophobic sense of dying, of running out of energy, and we did that by plunging poor Hugh into water for long periods of time. And we knew we would do take after take for performance reasons because it wasn't just about fighting. And it was incredible. We had to shoot that whole underwater sequence, all of it, in a day and a half, but he just never stopped. So that's kind of ... I don't know. I just, I do love action. It's so fun to direct. And I think it can be so expressive and also so beautiful. I think you can put real, really beautiful touches into it. And my DP, Paul Cameron, was so great, and Howard Cummings, my production designer. I was like, "I want a piano and I want this beautiful sunken world to be the environment." And they made it come alive.