The Untold Truth Of Mad Men

Often regarded as the series that sparked television's so-called "Golden Age," Creator Matthew Weiner's acclaimed hit AMC series Mad Men has earned a spot of honor in TV history—not to mention the hearts of fans. But beyond the Manhattan skyline, the smoke-filled Sterling Cooper offices, and Don Draper's beloved Old Fashioned cocktails lies a world of well-kept secrets. From character switch-ups to the story behind that ending, here's the untold truth of Mad Men.

HBO said no

Though HBO is widely considered the premiere prestige television network (lookin' at you, Westworld and Game of Thrones), and we all know how successful Mad Men turned out to be (hello, multiple Golden Globe Awards), the company's executives passed on an opportunity to air the show. Or, more specifically, HBO paragon and Sopranos creator David Chase did.

We know what you're thinking: it's odd that the network known for dark, gritty, and overtly adult content would reject a series full of that stuff. Matthew Weiner thought so, too. According to Chase, HBO expressed initial interest in the series, and appeared to indicate they'd back the show as long as Chase served as executive producer. Chase and Weiner reportedly tried to negotiate a mutually beneficial agreement, but things fell through. While Chase was "very tempted" by the idea of executive producing Mad Men and even directing the pilot episode, he declined and walked away, citing his desire to "move away from weekly television." To this day, it's unclear exactly why HBO passed, as the network never gave Weiner a full explanation—a lack of closure he appears to still struggle with. "I would go through David Chase's garbage if I was at HBO, trying to find more of what he does," he admitted. "But they were not like that."

However rocky the show's early road might have been, the ending was sweet: AMC saw Mad Men's promise and picked it up as its first original series. As president Ed Carroll later stated, the network "took a bet that quality would win out over formulaic mass appeal [and] there's no doubt it paid off."

A ton of actors wanted to be different characters

For a large portion of Mad Men alumni, the character they ended up playing wasn't their first pick—in fact, most of the main cast was gunning for different characters at the outset.

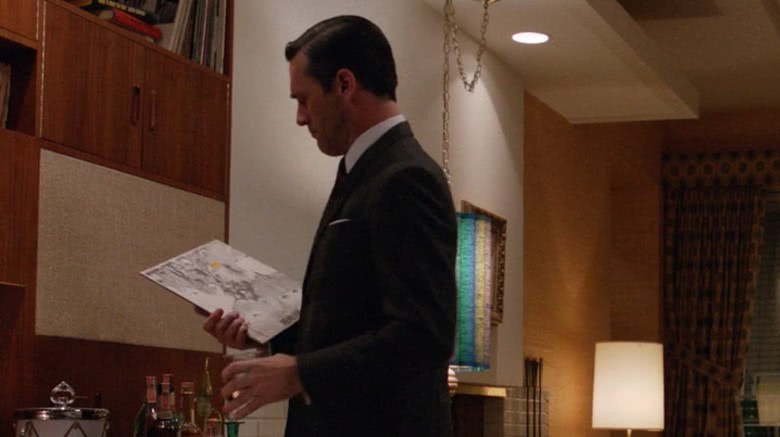

Take the silver fox John Slattery, famed for his sharp-tongued but oh-so suave portrayal of Roger Sterling. Slattery originally auditioned for Don Draper, but when the role went to Jon Hamm, Slattery remained a good sport. "It was apparent from the beginning how annoyingly good he was in that role," he said of Hamm as Don. "I don't think people appreciate how difficult it is to play something as subtle as he does. Trying to communicate so much from a guy who keeps his cards so close to his chest is almost an impossibility." Thankfully for us, we got to see Slattery work his acting chops as the part-time lothario, full-time advertising legend.

January Jones, who played the beautifully broken Betty Draper (later Francis), initially had her fingers crossed for the role of Peggy Olson. "I came in for Peggy twice," Jones once explained to The Hollywood Reporter. "[Weiner] said, 'Well, there's another role, but I don't really know what's going to happen with her.' He didn't have any scenes for me, so he quickly wrote a couple." This mysterious role ended up being Betty, and the rest was history.

Another actress yearning to portray the ambitious (if not slightly stubborn) secretary-turned-ad-woman was none other than Christina Hendricks. Hendricks first wanted to play Peggy, but was reportedly turned away for looking too mature. Instead, she auditioned for Midge, Don's mistress in the early seasons of the series played by Rosemarie DeWitt—and then landed the role she's perhaps most famous for, Joan Holloway Harris.

One thing's for certain regarding Peggy: Weiner knew Elisabeth Moss was the one from the get-go. After Moss auditioned, he was moved to tears.

Auditions are ambiguous

The audition process gets even more mixed up when you consider one actress's account of what's nestled in the script. Linda Cardellini, who played Don's rebel-with-a-cause neighbor and later paramour Sylvia Rosen, dished to TIME Magazine that because Weiner wanted to keep things under wraps, actors had pretty hazy auditions. "You audition with scenes and sides that have nothing to do with, and give away nothing about, your character," Cardellini explained. Not even the scenes actors tested hinted at what could happen onscreen. In Cardellini's experience, though the moments do eventually end up on the show, they're "not in the way you thought of [and] not in the way you prepared them or read them." Talk about commitment to avoiding spilled secrets!

Christina Hendricks didn't like Joan at first

Feisty, charismatic, and unexpectedly vulnerable, Joan is a character Mad Men fans hold near and dear. But in the show's infancy, Christina Hendricks had difficulty warming up to her role, finding Joan's personality harsh, cruel, and unrealistic. "I thought Joan was such a b—-, and I struggled sometimes trying to make her as real as possible because I thought, who would be so mean?" Hendricks said of the initial struggle.

Co-star John Slattery echoed Hendricks' early worry, admitting he didn't know what he was getting himself into. However, he was floored by her ability to turn the character into something incredible—which she totally ended up doing. (We're talking five-time Emmy nominee-level "incredible.") Slattery's first day on the Mad Men set was, coincidentally, his first taste of the fire-haired powerhouse. "My first scene... she's telling Peggy to 'go home, take a paper bag, tear out two eye holes and put it over your head," Slattery recalled. "It was that scene that kind of woke me up to the potential for this whole thing."

With time and productive talks with Weiner about Joan's complexities and true intentions, Hendricks melted into the role, and Slattery speaks for millions in saying that Hendricks took Joan to heights greater than the Mad Men team ever imagined.

Mad Men has connections to The Sopranos

Mad Men didn't get its official start until the late 2000s, but the story truly started before the turn of the century. In 1999, after experiencing a surge of inspiration while working as a staff writer on Ted Danson's CBS sitcom Becker, Weiner whipped up the Mad Men pilot script. Three years later, he sent it off to none other than David Chase (remember him?) as part of his application bundle for a writing position. Chase was impressed with Weiner's work, and offered him a job on The Sopranos in 2002. "He told me later that he insisted that he be submitted—his agents didn't want to do it. And what was submitted to me was the pilot for Mad Men," Chase recalled. "And it was quite good, and I met with him and he was hired." However, we all know where the pilot ended up: not in Chase's hands at HBO.

Yet another link to the acclaimed crime drama concerns that fated pilot. The first-ever episode of Mad Men was shot while The Sopranos took a hiatus in its final season, which ran in two parts during 2006 and 2007. Knowing he'd have the time to pull together something solid, Weiner pooled his resources and enlisted the help of a few fellow Soprano employees to make it happen. AMC's former executive programming and production VP Rob Sorcher reminisced, "[Weiner] asked Alan Taylor to direct while all his buddies on The Sopranos were on hiatus. They shot the pilot in 10 days in Queens."

There was a year-long gap between the first two episodes

Huge gaps are common in the Mad Men timeline. According to Weiner, not only was there a staggering seven years between the moment he wrote the pilot script and when he finally got around to penning the second episode, there's also a space between the filming of the initial two episodes.

Weiner wanted to fine-tune his vision, flesh out Don's backstory, and rework certain elements that would allow the world that existed in his mind to translate as a regular series. "A lot about my vision changed in terms of how the storytelling would be done. Ultimately it was done very much in the pilot the way we continued to do it," he explained. "I didn't know if it was just going to be a premise, or if we were going to be able to do something like that every week." Weiner finished work on The Sopranos while AMC sorted out a studio partner to pick the series up, a gap that gave him time to "think about what was going to happen in the show." He worked off an original film script he'd written, called The Horseshoe, that eventually became Don's entire history. Time heals all wounds, but in Mad Men's case, it can also create something beautiful.

The show wasn't actually filmed in New York

It seems one bite out of the Big Apple was enough for Mad Men. Though many people bask in that New York state of mind, Weiner and co. had their eyes to the west, on sunny California. Which is sort of ironic, considering the Sterling Cooper offices actually divvied up their creative forces and became a bi-coastal ad agency in the show's later seasons. Following the pilot episode, the cast and crew packed up their belongings and settled down in Los Angeles for the remainder of the series' seven-season run.

The secret behind the smokers

Let's clear the smoke and mirrors by, well, clearing up the mystery of the show's ever-smoky rooms. The good news is that AMC and Weiner weren't total masochists and didn't actually force the actors to chain-smoke. Instead of the real deal, which Weiner has explained makes actors "agitated," "nervous," and prone to vomiting, Mad Men stars take drags of herbal cigarettes. Not as harmful as their tobacco counterparts—but still disgusting, according to Hendricks.

There are a fair few on the show who've dodged the proverbial bullet altogether—and there's a reason for it. As explained on the DVD commentary, the overall smoking standard is quite simple: "If the actor playing a character has been a smoker (or still is a smoker), then the character is a smoker on the show. If the actor never smoked, then his or her character is not a smoker." So Vincent Kartheiser, who plays the scrappy Pete Campbell, and Rich Sommer, who portrays the lovably sarcastic Harry Crane, were apparently never bitten by the nicotine bug, while other Mad Men actors had picked up the smoking stick at least once in their lives.

An onscreen tragedy followed a real one

Character deaths are a dime a dozen in many television shows, but in Mad Men, they were surprisingly uncommon—so in season two, when Pete Campbell's father died in a terrifying plane crash, it was particularly devastating. The show incorporated the 1962 crash of American Airlines Flight 1 that killed all 95 passengers after it landed in Jamaica Bay, but the historical tie-in isn't what's particularly shocking; it's the reason why Andrew Campbell was written out in the first place. As it turns out, the actor who played him, Christopher Allport, died in real life in an equally horrific accident. Allport passed away on January 25, 2008, in an avalanche near the Mountain High ski resort in California's San Gabriel Mountains. He was just 60 years old.

There's a limit on swearing

Because Mad Men found its home with AMC and not HBO, things panned out a bit differently in the vulgarity department. While the HBO rendition might've seen Don dropping more than a few F-bombs and perhaps even featured some extra skin, there were restrictions on what Weiner could and couldn't do on AMC with a TV-14 rating. "Mad Men is TV-14, not even TV-MA. I'm allowed three 's—s' a show. I can say 'Jesus,' I can say 'Christ,' but I can't say 'Jesus Christ' unless he's actually there," he explained. Weiner and the Mad Men team made the most of their range, punching out just the right amount of adult language in each episode.

Weiner's wife was a major influence

A passion for writing ties Weiner to his life partner, Linda Brettler, who was also a noteworthy contributor to Mad Men. During the series' run, Brettler read each script and offered her husband feedback, and her comments, which Weiner refers to as her "weighing in on things," came to a head in the season five episode "Lady Lazarus." According to Weiner, his wife actually pitched the idea that Don opens a set of elevator doors, only to find no carriage waiting for him, just a cavernous shaft. This is, of course, deeply symbolic of Don's emotional state in the episode. After Megan leaves Sterling Cooper and rejects Don's values, Weiner was confronted with the challenge of "express[ing] the deep feelings of loss" he experiences when saying goodbye to her. The missing elevator did just that, and Weiner has his own wife to thank.

'Zou Bisou Bisou' was a hit

Don Draper may not have entirely enjoyed his hot-to-trot wife's rendition of the 1960 Gillian Hills hit "Zou Bisou Bisou," but music lovers definitely did. Sung by Jessica Paré in a particularly sultry number meant to celebrate Don's 40th birthday, the show's version of the French yéyé song burst out of television screens to the top of Billboard's World Digital chart where Paré's cover secured the number one spot. An accomplishment certainly worthy of the kisses the song's lyrics center around.

Securing a Beatles song cost $250,000

The Beatles taught a generation that all you need is love, but to license song rights for a television series, you need a lot more than emotion. Weiner (via production studio Lionsgate) shelled out a massive stack of cash to legally use the 1966 track "Tomorrow Never Knows" in season five's eighth episode, "Lady Lazarus."

A quarter of a million dollars was the price tag for an "actual master recording of The Beatles performing" and not just "someone singing their song or a version of their song." Weiner believed this brought "a certain authenticity" to the show, and explained that regardless of what people think, the lofty price has nothing to do with the monetary aspect at all. Rather, licensers like the Beatles are more "concerned about their legacy and their artistic impact." In any case, it was money well spent.

Harry Crane could've been the falling man

Think of the Mad Men intro. What's the first image that pops into your head? Probably the silhouette of a man in a suit, falling from a New York City building. It is, after all, one of the most iconic symbols in the show's history—and Harry Crane (Rich Sommer) might've ended up recreating that very fall.

Weiner planned to give Harry the axe during the show's first season via suicide. He was supposed to leap from the Time-Life building to his death in a manner eerily similar to what we see in the slate sequence—and it's even joked about in season four when he says he "wishes his new office had a second floor so he could jump out of it." While we know he wound up climbing the corporate ladder instead, and the animation is actually modeled after Jon Hamm, it's still a little creepy.

AMC didn't pay to use the Coke ad

The network may have paid a pretty penny for that Beatles song, but Mad Men skipped out on purchasing the rights to use the original "Buy the World a Coke" hilltop ad at the end of the series' finale. A Coca-Cola spokesperson confirmed that "no money exchanged hands," as the company didn't know ahead of time that Don Draper would use the fizzy drink to bid farewell. However, Coke didn't seem upset about it—in fact, it appears the company is actually happy to share the feel-good ad with Mad Men fans pro bono.

"We've had limited awareness around the brand's role in the series's final episodes, and what a rich story they decided to tell," the spokesperson told People. "Mad Men is one of the most popular TV shows of all time, and 'Hilltop' is an iconic piece of Coca-Cola history. The finale gave everyone inside and outside the company—some for the first time—a chance to experience the magic of 'Hilltop' within the context of its creation and the times." What a way to embody the ad's message: bringing the world together in perfect harmony, even if it is just the world of Mad Men.