Candyman Review: Art Attack

In recent years, the "rebootquel" has become a growing trend in Hollywood, as studios strive to capitalize on the strength of the older properties they own, while subtly acknowledging modern audiences have stayed out the loop. This is why 2011's "The Thing" is as much a remake as it is a prequel to John Carpenter's chilly horror, or why 2018's "Halloween" ignores the existence of any film in the franchise after the only one still remembered fondly. After years in development hell, "Candyman" has returned to the big screen courtesy of director Nia DaCosta, who has wisely assumed that nobody remembers either of the two sequels that came after the 1992 original.

Her film is a direct continuation of the mythology established in that film, but can easily stand separate from it. The events of the first film now appear as folklore within this universe, an expansion on the original myth of Candyman that, to a new generation telling the story, feels like it's always been part of it. Fans of the original will likely be impressed with how DaCosta adds further weight to this mythology, slowly unraveling until it reveals itself to be a spiky piece of social satire that feels the very obvious product of its co-screenwriter and producer, Jordan Peele. The problem is, the film feels like it was very much reverse engineered from this third act, the opening hour an onslaught of intriguing ideas which distractingly feel like table setting for a finale that can more cohesively bring these together. It's a horror film that aims to get in your head rather than under your skin — but with the glaringly obvious manner in which it addresses many of its themes, no idea is left too ambiguous for you to truly linger on.

Candyman: The Next Generation

The story takes place in 2019, approximately a decade after the towers in the Cabrini Green neighbourhood in Chicago were torn down. But the memories of Candyman murdering those who say his name five times in a mirror remain all those years later, now the neighbourhood has been rapidly gentrified, its last remaining housing from that era standing eerily unoccupied. Artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) is one of the affluent millennials who now lives in the gentrified apartment buildings in Cabrini Green, alongside his girlfriend, the art gallery director Brianna (Teyonah Parris). One day, her brother (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett) comes to visit, telling Anthony the story of Candyman — and it sparks an obsession.

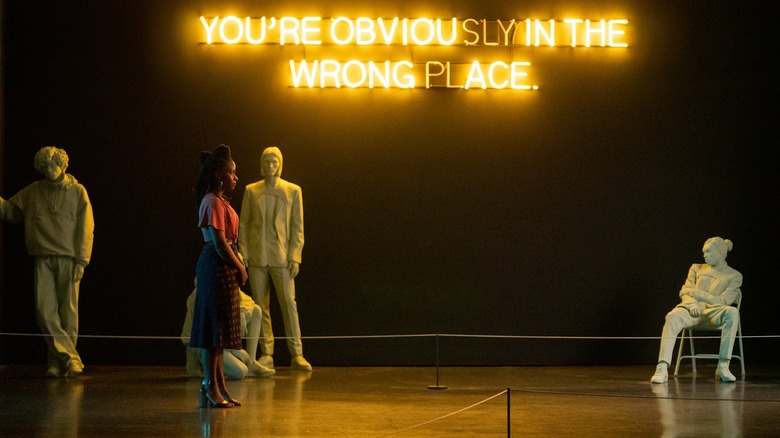

He commits to doing an art installation piece based on the myth to be shown in the upcoming exhibition Brianna is curating, heading deeper into the neighborhood, and discovering the recordings of Helen Lyle, whose fate in the 1992 "Candyman" is now part of the in-universe folklore here. The piece is entitled "Say His Name," with Anthony all but daring people to say Candyman five times into a mirror as a form of social commentary, the demon who haunted this neighborhood now utilized as a metaphor for urban deprivation in the very way Clive Barker (who wrote the short story which inspired this franchise) intended. Of course, this has ramifications beyond making people aware of weighty social issues, as Candyman re-emerges, with Anthony soon realizing his fate is not only about to become part of this mythology, but that it was always entwined with it.

That aforementioned short story by Clive Barker, 1984's "The Forbidden," took place in a working-class area of Liverpool, Candyman representing the social deprivation in many British housing estates. In this regard, making a film both about gentrification feels like the logical continuation of this mythos — even if it does feel at its best when acting as a satire very explicitly poking fun at wealthy artists who want to explore the topic. These early sequences in the art world, quite bizarrely, recall the Netflix horror "Velvet Buzzsaw," in which Jake Gyllenhaal played a camp art dealer in the midst of a spate of "Final Destination"-style killings. DaCosta clearly has a fondness for the ideas she's exploring, but the wider horror around it isn't afforded equal weight, meaning the moments it does become a slasher feel strangely jarring.

At times, these slasher sequences feel like mandated studio additions. A scene where some high school girls decide to say Candyman's name into the mirrors in their school bathroom does have the impressively staged kills a fan of this genre would be eager for, but doesn't add any weight to the story. When characters who are formally introduced get death sequences that are effectively staged (and often left entirely to the imagination), a moment that neither extends upon any of the social issues it sets out to explore nor pushes the narrative forward feels all the more jarring. The film is a tight 91 minutes, and it feels like more time could have been used to weave its ideas into something more cohesive, and more accustomed so subtlety.

Bold ideas... that could have used more room to explore

One interesting idea teased out is the theory, heard in the then-unbeknownst Helen Lyle's research, that Candyman is a collective delusion, a natural result of a community turning inward on itself after years of neglect. The effective third act turns this idea entirely on its head, its wider commentary on gentrification becoming, in the hands of at least one character, a passionate defense as to why communities need a Candyman of their own to fight back against it. Horror sequels have often reimagined villains as heroes after producers have discovered they've got their own fanbase — look no further than the recent "Don't Breathe 2" to see this trend alive and well.

This is, however, the rare case of a film actually putting forward the argument as to why they should be reconsidered. The complexities of this make for an exciting third act, but there remains the nagging feeling this should have been explored much earlier in the runtime. There's no breathing room for the best ideas, with the things that are explored in-depth delivered largely via exposition. It's the rare horror that might be more effective were it less eager to show its hand at all times, and take its time to properly develop ideas instead of spelling them out.

There is a lot to admire in "Candyman," but this bold continuation of the franchise often proves frustrating. It's a film commendable for its sheer wealth of ideas, but ever so slightly disappointing in the way it often struggles to balance a more thorough examination of them with its requirements as a horror. You won't say its title five times in a mirror, but you will probably give it three stars.