Biggest Unanswered Questions In Futurama

Maybe "Futurama" never approached the popularity of that other animated series Matt Groening created for the Fox Network, but it can match "The Simpsons" in singularity, if not raw numbers. "Futurama" can be ripped off by other shows, of course. That happens all the time. But the still unfolding history of television demands that "Futurama" remains one of a kind.

The adventures of the Planet Express package delivery company — staffed by time-displaced slacker Philip J. Fry, mutant captain Turanga Leela, and sleazebag robot Bender — stuck around on the Fox Network from 1999 to 2003, then continued in the form of straight-to-video films until its revival on Comedy Central that lasted from 2010 to 2013. Ironically, all of this would only be possible in a pre-streaming universe. We owe "Futurama" as we know it to antiquated forms of media distribution.

The way "Futurama" shook out, history will remember it as pop culture's bridge between reverent sci-fi satire of early '90s, exemplified by "Mystery Science Theater 3000," and mid-2010s counterparts in the spirit of "Rick and Morty." Quite like the latter program, the mythology of "Futurama" resembles a Rube Goldberg-ian labyrinth of chronological and inter-dimensional chutes and ladders. Sci-fi geeks love convoluted time travel nonsense, after all. But despite the total of 140 episodes-worth of "Futurama" content, the franchise contains its share of matters left unresolved. And we're not talking about nit-picky "plot holes" — we mean issues that call the entire fabric of "Futurama" reality into question.

How come people in the future use outdated appliances?

By necessity, "Futurama" puts its comedy ahead of its sci-fi. Not every gag or even storyline revolves around the fact that most of the program's pertinent events take place in the 31st century. But doesn't the vision of mankind's destiny presented by "Futurama" look a little too similar to our everyday reality here in the 21st century?

For instance, the 2001 episode "Roswell That Ends Well" gets rolling when Fry puts an Iffy Pop tin in the microwave, and calamity ensues. But why would a Jiffy Pop equivalent still exist in the year 3000? How is it possible that in 1,000 years, nobody invented a superior means of cooking instant popcorn? For that matter, why are microwaves still commonly used in "Futurama"-era kitchens? How can it be that microwaves remain the most efficient and affordable means of flash-heating meals, despite literal centuries of technological advancement?

Folks on "Futurama" use antiques on a routine basis, in many aspects of life, and it makes no sense. Why are television sets on "Futurama" usually thicker than screens we gaze into in back here in the 2020s? Characters on "Futurama" still speak to each other through telephones on occasion. We're not even close to the year 3000, and industrialized human society has already outgrown telephones.

Perhaps it's safe to say that from a technological standpoint, the vision of the 31st century presented by "Futurama" isn't very ambitious.

Whatever happened to Guenter the monkey?

A standout from the all-bangers 1999 of "Futurama," "Mars University" is oft-cited as among the all-time best of the series. A 40% homage of "National Lampoon's Animal House," "Mars University" introduces Guenter — a monkey who commands genius-level intellect as long as he wears an Electronium Hat invented by Professor Farnsworth. At the story's conclusion, Guenter decides he'd rather not be a genius, nor does he wish to revert back to below-human, monkey-level smarts. Rather, he chooses moderate intelligence and enrolls in business school.

Guenter turns up again at the opposite end of the "Futurama" timeline in "Fry and Leela's Big Fling," which premiered in 2013. Guenter's post-collegiate life has him working at an office on planet Simian 7, where only monkeys and monkey-adjacent nonhuman creatures are allowed. It's a planet of the apes, of sorts.

However, the Planet Express arrives on a gig, Guenter recognizes former classmate Amy in spite of her incredibly convincing marmoset costume, and takes them on a tour around town. One thing leads to another, and Simian 7 authorities discover Amy's status as a non-marmoset human. Guenter is shot with a tranquilizer dart as the Planet Expressers escape ... and that's the last we see of Guenter.

So, was Guenter punished for knowingly escorting a disguised human into Simian 7? Also, Guenter can't use human language without his specialized derby, but the other monkeys on Simian 7 can talk without any apparent problem despite their complete lack of intellect-enhancing hats. Weird!

Whatever happened to Flexo?

Among the many recurring secondary or tertiary "Futurama" characters, Flexo was probably the easiest to draw.

Sometimes mistaken for Bender's evil twin, Bender's good twin Flexo is a bending unit with a conscience, wishing only to bend various objects — girders, metal sheets, and similar items in need of bending — while doing as little harm to the world as possible throughout his technically soulless existence. But the circumstances under which we see Flexo for the final time are potentially traumatic.

In "Attack of the Killer App," first aired in 2010, the Planet Express gang stop by an e-waste recycling festival in order to dispose of aging electronics in a manner less directly ruinous to the Earth than stuffing them into a landfill. By chance, Bender stumbles into Flexo, who has dutifully thrown himself into a disposal dumpster. It appears Flexo's model — which also happens to be Bender's model — has been declared obsolete and dangerously outmoded.

The audience sees the potentially toxic trash transported to a so-called "Third World" planet, but could it be that Flexo's story ends off-camera, with the bearded-bender unceremoniously melted to his doom? We think not. Flexo is a far too important "Futurama" character to be casually and pointlessly killed off. Perhaps he escaped? Was his consciousness transplanted into a more up-to-date bending unit? Was he recycled into a different kind a machine? Perhaps a squeezing or a lifting unit? Tell us!

If Yivo gave humanity the idea for Heaven, then who built Robot Hell?

"Futurama" stops short of offering us answers to any heavy questions along the lines of, "Why are we here?" "What is the purpose of existence?" or "How could 'The Simpsons' have possibly gotten so bad?" But it comes about as close as any half-hour comedy cartoon has or probably ever should.

For instance, in 2008's "The Beast With a Billion Backs," the immortal extradimensional celestial entity known as Yivo explains that early humans invented the Christian concept of Heaven by observing the clouds of pleasant-smelling fumes generated by the myriad holes in his planet-sized body. But if there's a tangible explanation for where the idea of Heaven comes from, then who invented Robot Hell?

In a direct sense, the architects of Robotology fashioned Robot Hell to threaten its adherents into compliance. But that doesn't account for where the concept of Robot Hell originates. Did ancient man encounter a different extradimensional creature who spat fire and brimstone? Could it be that the secret history of every major Earth religion can be identified and unpacked with a deep dive into "Futurama" mythos? We think the answer to that question is "obviously."

When did English become the literal universal language?

This is an issue we could just as easily raise with at least a few other sci-fi/fantasy franchises — namely "Star Wars," plus the entire cosmic section of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. But just because "Star Wars" and Marvel do it, that doesn't make it okay.

Let's look at the planet of Omicron Persei 8, terrorized by the despotic cannibal Emperor Lrrr. As is documented in 1999's "When Aliens Attack," Lrrr invades Earth in a fit of rage over an interrupted episode of ersatz "Ally McBeal" called "Single Female Lawyer." Since Lrrr grew up on a planet with environments, culture, and legal infrastructures all totally different from Earth, how does he understand and comprehend "Single Female Lawyer" enough to enjoy it recreationally? How does he even know what a "lawyer" is?

The Omicronians all speak English — an Earth language — just like many of the other extraterrestrials in "Futurama." Doesn't that seem wildly implausible? Sure, non-Earthling languages show up in the backgrounds — sometimes written, sometimes spoken — in numerous scenes. But whatever language barriers exist never cause enough confusion or inconvenience to slow down a plot. When it matters, everyone on "Futurama" speaks American-style, 20th-century English, somehow.

On "Doctor Who," the magic of the TARDIS creates a linguistic field that instantly translates any and every language the Doctor and their companions come across. Does the linguistic conversion field of the TARDIS extend all the way to "Futurama?"

A lot of stuff from the 21st century is still around after the year 3000

It's far from Pollyanna to anticipate racial division as a concept gradually phasing out of human civilization. Way back in the day, racist Americans didn't consider Irish and Italian folks white — "white" being an elastic euphemism for the ethnic majority, in this instance. After a few generations of intermarrying, while Irish and Italian cultural identities remain influential, both have been absorbed into the amorphous idea of "white people." This occurred within less than 250 years, so it stands to reason that the same thing will pretty much happen with all the other human races after four times that amount of time.

Racism doesn't seem like it's still a thing in the future according to "Futurama," but races still exist as a concept in more-or-less the same way they do today. Of the main human characters who originate in the 31st century, Professor Farnsworth appears to fit our contemporary definition of a white person, whereas Amy Wong scans as American with Chinese lineage and grew up on Mars — which, by "Futurama" rules, might as well be western Massachusetts. And Hermes Conrad famously limboed for the Jamaican Olympic squad. And if the Olympics still exists, that means individual nation states also still exist. You'd think future people would've definitely outgrown those clunky old things.

Sometimes it feels like the future of "Futurama" is just the present except with a bunch of stuff from old sci-fi TV shows and movies squished in.

What happened to that motto from the first episode?

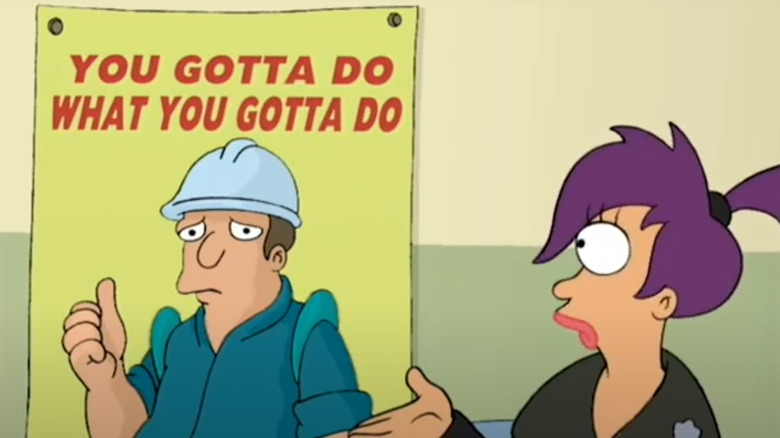

When Fry and Leela first meet in "Space Pilot 3000," Leela works as a fate assignment officer and awaits Fry outside the cryotube in which he's spent the previous 1,000 years frozen. She breaks it to Fry that here in the future, everyone is assigned a lifelong vocation according physical and mental metrics determined by a single round of tests. If they refuse, they're fired ... out of a cannon into the sun. When Fry expresses pure horror at this prospect, Leela gestures towards a poster depicting the motto of the new millennium — "You gotta do what you gotta do."

In a vacuum, the pilot appears to set up a series in which defiance of state and/or corporate-mandated life assignments would, at the very least, remain an ongoing theme. But career chips are rarely brought up after "Space Pilot 3000." Nobody ever says or gestures towards a poster that reads "you gotta do what you gotta do" again. In fact, hardly anybody on Earth as seen during "Futurama" ever vocally acknowledges these oppressive conditions or expresses an attitude about them one way or another.

Maybe Fry's not the only person who runs away from his fate assignment officer? In fact, maybe everyone else also does that?

How do the circuitry and mechanics of Bender's robot body work?

We knew this one kid in college who went out of his way to screech about how the "science" didn't "make sense" in every movie or TV show he saw ... except "Battlestar Galactica," for some reason. We don't want to sound like that guy — and we're pretty sure the "science" of Cylons doesn't "make sense" either — but we do have some science-ish concerns regarding Bender.

We're not saying the problem with Bender is he's impossible according to our current understanding of mechanics and A.I. because "Futurama" clearly plays by a different set of rules. We're just not sure what those rules are. Sometimes Bender can operate his torso and limbs, even if his head has detached from the rest of his anatomy. Does that mean his head controls his body via radio signals of some sort? Is that what his antenna is for? But wait — in "A Head in the Polls," Richard Nixon completely takes over control of Bender's body. Does that mean Bender's head can control his body remotely unless a different head gains control?

Plus, Bender frequently uses his torso as a kind of mobile storage unit, so why does the sound of its front door swinging shut often resonate with a hollow-sounding clank? Is Bender's torso bigger on the inside, just like the TARDIS? We need answers, people.

How did Slurms MacKenzie become the original party worm?

No one will ever know for sure how much money the creative minds behind "Futurama" left on the table by killing off Slurms MacKenzie at the end of "Fry and the Slurm Factory" — his one-and-only episode.

But we think it's a lot.

The primary spokesperson and de facto mascot of Slurm — the universe's soft drink of choice — Slurms MacKenzie is duty-bound to party all night, every night, indefinitely — until his corporate overlords allow him to spend his time otherwise. In this way, he celebrates the message and fun-centric lifestyle associated with Slurm and other highly addictive products produced by the same corporation. But by the time Slurms encounters the Planet Express crew, he's exhausted, jaded, and desires only a quiet evening in with a good book and an early night's rest.

Let us imagine, for a moment — how did Slurms get to this point? How does an mild-mannered space worm become the original party worm? What tasks did Slurms perform to achieve the mantle? What drives a worm — or any being — to party so hard that their capacity for partying becomes known (and feared) across the galaxy?

"Futurama" left all of these threads hanging, and it's surely too late to correct the mistake with a "Better Call Saul"-style prequel series about Slums' early years ... unless we find out his species of worm originally came from Dreamland, in which case, there are oodles of time.

If time restarts at the end of Meanwhile, then when do Simpsorama and Radiorama take place?

The continued production of "Futurama" was often a dicey prospect throughout both its tenures on television. Ergo, practicality entailed that it produce multiple stories that could, if need be, serve as the series finale. "The Devil's Hands Are Idle Playthings" ties up the show's run with Fox. The straight-to-DVD movie, "Into the Wild Green Yonder," was designed as a possible sendoff. But "Futurama" ends for reals with 2013's "Meanwhile." After a glitching space-time continuum allows them to experience a literal lifetime together, Fry and Leela decide to do it all over again by hitting a reset button to bring the universe's timeline back to its beginning.

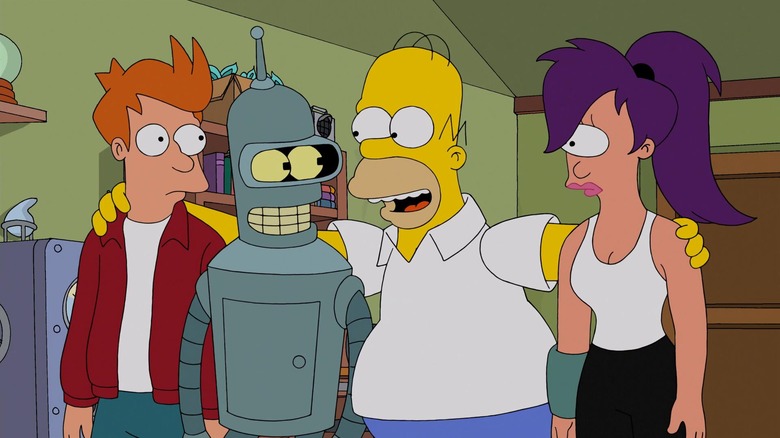

However, the Planet Express crew make a one-off return to Fox with a "Simpsons" crossover episode, "Simpsorama," in 2014. A few years later in 2017, the voice acting cast reunited to record "Radiorama" — an audio-only episode on The Nerdist podcast. So if "Meanwhile" closes the loop of the "Futurama" timeline, when do the events of "Simpsorama" and "Radiorama" take place?

In theory, both could occur at more-or-less any point between the start of season 2 and the series finale without disrupting the established continuity. But that would mean every other episode of "Futurama" that doesn't include any serialized elements could also, in theory, take place at almost any time in "Futurama" history.

Why does every sci-fi franchise need a confusing timeline? Seriously. Can you tell us?

Is Futurama a utopian or dystopian vision for the future?

As has probably been pointed out before, all TV sci-fi tends to land somewhere on the spectrum between "Star Trek" and "The Walking Dead" — the former is the quintessential optimistic vision of mankind's future, the latter is its negative counterpart. On "Star Trek," humans live in the stars; all racism and scarcity of basic living essentials has been erased. On "The Walking Dead," humans have devolved into literal monsters and eat each other alive.

Clearly, "Futurama" doesn't approach either of those extremes, but which does it come closest to? MomCorp's control over the global population seems pretty dystopian. But not unlike "Star Trek," "Futurama" presents us a world where humans, sentient robots, and extraterrestrial beings work together towards common goals.

Maybe, despite some of its high-concept aspirations, "Futurama" doesn't attempt to offer much in the way of the big picture. In each of the show's three endings, Fry and Leela either get together or celebrate their relationship, indicating that the core of "Futurama" is an almost retrogressively conventional story — boy meets girl, boy falls for girl, girl eventually caves and settles, and the two live happily ever after.

Perhaps that level of simplicity is necessary to stabilize the show's countless zany components, but it also prevents "Futurama" from forming any overarching philosophy. Maybe that's okay. Maybe the audience for "Futurama" wants to think while they laugh, so long as they don't have to think that hard.