The Untold Truth Of Blade Runner

"Blade Runner" is one of our favorite science fiction movies — and it's also one with a fascinating (and sometimes troubled) history. Its behind-the-scenes story is a tangled one, full of personal clashes, thoughtful creativity, and plenty of things that turned out right only because they first went wrong.

But despite all the drama, we're sure of one thing: Everything that happened worked a weird kind of alchemy, turning this movie into cinematic gold. After all, we're not the only ones who think highly of it. The American Society of Cinematographers voted it their second-most influential movie of all time, and it also made the American Film Institute's list of the 100 Greatest American Films of All Time. And certain parts of it — replicants, the enigmatic Voight-Kampff test, beautiful and sometimes unsettling quotes — show up in pop culture over and over again.

So how did this happen? What gives "Blade Runner" its lasting impact? Let's take a look at the untold truth of this particular masterpiece.

The movie has the wrong name

"Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" is a hard title to fit on the poster, so when the "Blade Runner" team adapted Philip K. Dick's novel, it makes sense that they changed the name.

But after that, as Variety explains, it gets complicated because the term "blade runner" never even appears in the original novel. Instead, it dates back to the obscure science fiction author Alan E. Nourse, who used knowledge gleaned in his medical doctor day job to write a dystopian future full of eugenics and black-market medical care in "The Bladerunner." In this novel, "bladerunners" are the middlemen who smuggle scalpels and other surgical and medical tools to rogue doctors. Which makes sense ... but why port it over to a completely different future and use it to describe android-hunting cops?

Well, the term for these middlemen had a crucial middleman of its own: off-the-wall genius William S. Burroughs, the author of "Naked Lunch." Burroughs loved Nourse's original novel so much that he wrote a legendarily weird film treatment of it, "The Blade Runner," and sent it to Hollywood. When no one bit, Burroughs published it as a standalone work — one that found its way into screenwriter Hampton Fancher's library. When Fancher, Ridley Scott, and producer Michael Deely were trying to brainstorm a more unique job title for Deckard — in Dick's book, he was just a cop, plain and simple — Fancher took a look at his shelves for inspiration. There was "The Blade Runner," and his problem was solved.

Tragedy brought Ridley Scott to Blade Runner

Ridley Scott shouldn't have been available to make "Blade Runner." If everything had gone according to plan, he would've been too tied up adapting "Dune." In fact, The Directors Series notes that when Scott was first offered the chance to direct "Blade Runner" — then called "Dangerous Days" — he turned it down. It sounded intriguing, but his plate was already full. He was only going to take on one major science fiction movie at a time.

But tragically, everything got upended. Frank Scott died of skin cancer, and losing his beloved older brother sent Ridley Scott into an emotional tailspin. "I was so down," Scott told Vanity Fair. "I needed to do something." And "Dune" wouldn't even go into production for another year. But "Dangerous Days" was still available, so Scott took it on ... and turned it into an immortal work of art.

Scott's grief shaped "Blade Runner" in other ways too. At The Directors Series, Cameron Beyl writes, "In this light, Scott's approach to 'Blade Runner' serves as something of a grieving process for his late brother — an intensely personal work ... [and] a heartfelt meditation on creation, death, and loss— the beauty of life as defined by its ephemerality." Considered in that light, the film gains even more power and meaning.

A future shaped by the past

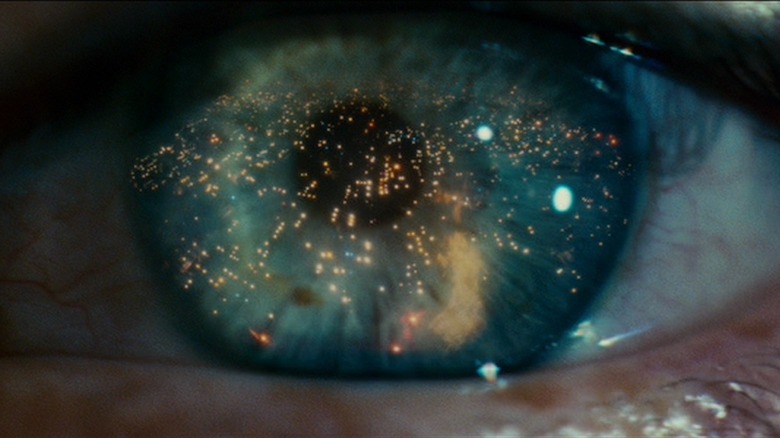

How does "Blade Runner" imagine an utterly convincing future? It draws on the past — especially Hollywood's past, pulling from film noir to create its own mean L.A. streets.

The British Film Institute's "anatomy of a classic" feature on the film traces some of its inspirations. They range far and wide — even including Edward Hopper's iconic painting "Nighthawks," with its quietly lonely diner patrons — but classic Hollywood comes up again and again. One of the best pulls is Rachael's hairstyles and costuming. As fashion site GlamAmor explains, her styling draws heavily not only on the 1930s and '40s but on specific films: "Mildred Pierce" and "The Thin Man."

Most of all, the film noir inspiration shows up in Harrison Ford's Deckard. With his trench coat, jaded decency, and semi-outsider status, he's an old school hardboiled detective, plain and simple. Even Deckard's voiceover — often derided by fans and ultimately removed from the Final Cut edition — belongs to this noir sensibility. In fact, even though this exact voiceover track suffered from studio-mandated dollops of exposition, Ridley Scott liked the basic idea and even intermittently planned on using one himself. Screenwriter Hampton Fancher confirmed this in the making-of book "Future Noir" (via Den of Geek): "Scott was after the feel of a '40s detective thriller, so he liked the idea of using this film noir device." All these familiar movie tropes help sell us on this darkly strange new world.

Edward James Olmos invented Cityspeak

Edward James Olmos' enigmatic character Gaff often speaks in a kind of linguistic hodgepodge of several real-world languages. In the original cut of the film, Deckard's voiceover explains that this "lingo" is called "Cityspeak."

And before Olmos got his hands on the script, that's about all anyone knew about it. Cityspeak was a blank slate, just a "funny language" placeholder. It caught Olmos' imagination like a hook, and it seemed like a key part of Gaff's character, something that Olmos had to understand. So, as he explained in "Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner" (via Ponying the Slovos), "My first idea was to put a mixture of genuine Spanish, French, Chinese, German, Hungarian, and Japanese into Cityspeak. .... Then I went to the Berlitz School of Languages in Los Angeles, translated all these different bits and pieces of Gaff's original dialogue into fragments of foreign tongues, and learned to properly pronounce them."

His efforts paid off, at least for "Blade Runner" fans who've put in their own hours of work analyzing and translating Gaff's bits of Cityspeak. This rich enmeshing of futuristic L.A. language is exactly the kind of worldbuilding flourish that makes "Blade Runner" one of the best science fiction movies ever made.

'You wear your guts on the outside.'

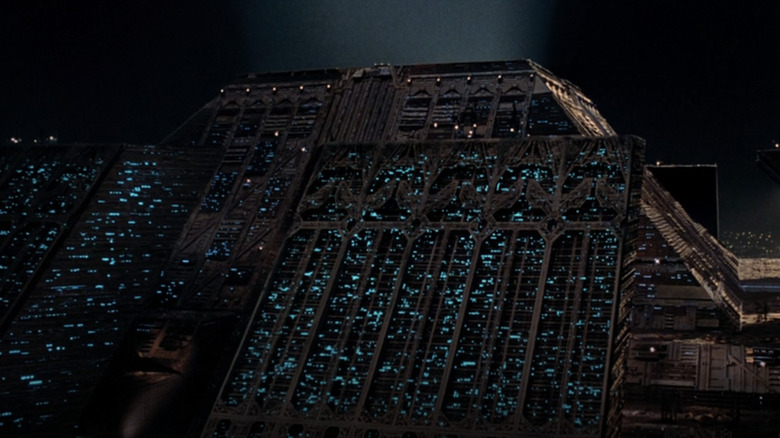

"Blade Runner" has some of the greatest sets of all time. If we close our eyes, we can see its dark and rainy futuristic Los Angeles, jam-packed with people and buildings, and all the details fit together perfectly. And, of course, there's a reason for that. A lot of thought went into the film's production design — especially its architecture.

As Ridley Scott explained to American Cinematographer, old buildings are difficult to maintain, and when they're in the middle of urban environments, they can be even more difficult to raze and rebuild. "Eventually, you'll just have to 'retrofit' things on the face of the building rather than having to pull half the side off. ... It's going to be simpler just to smack things on the outside. So maybe buildings will start to be designed from the inside out. You wear your guts on the outside. That gives us a picture of a textured city." And just as the buildings have gotten more and more piled-on, so have the streets, which intentionally evoke a kind of desperate overcrowding.

It takes money — and a flying car — to go higher. And it takes even more money to build something new: Tyrell's 700-story pyramid full of polished black marble. It's like an Aztec temple reimagined as an office building — the production designer called it "Establishment Gothic" — and it quickly signals Tyrell's incredible power. Now that's some efficient storytelling.

The best Blade Runner lines weren't even scripted

When it comes to "Blade Runner" quotes, two have always stood out head and shoulders above the rest: Gaff's last question to Deckard — "Too bad she won't live. But, then again, who does?" — and the "tears in rain" speech Roy Batty makes as he dies. Even reading them can give you chills. But what makes them particularly remarkable is that they were invented by the actors themselves.

The British Film Institute's "anatomy of a classic" article details how Rutger Hauer saw Roy as the hero of the piece and pushed and pushed for his interpretation — Roy as a kind of embodiment of charisma, "a romantic, flamboyant, sexualized dandy: half-rock star and half-terrorist." His influence over his character and his persistence in advocating for it led Scott to give him permission to write Roy's final speech.

And Edward James Olmos exerted similar control over Gaff, really shaping his character from behind the scenes. In an interview with The AV Club, he explained how he not only came up with Gaff's whole family tree but also his character's most memorable line, saying, "I wrote that. It was really fun. I just couldn't believe [it] when he left it in." He meant it partly as Gaff's subtle nod to Deckard's replicant status — Olmos is firmly in the "Deckard is a replicant" camp — but however you interpret it, it's a fantastic bit of writing.

A flying car you can believe in

We could write a thousand articles on the intricacies of the "Blade Runner" worldbuilding, but one of our favorite stories is how the production team designed the film's flying cars, also known as Spinners.

Right from the start, Ridley Scott insisted that their flying cars had to be a little different from everybody else's — no plane-like wings or standard propellers. Designer Syd Mead told American Cinematographer that while he came up with a plausible idea pretty quickly, the real challenge wasn't a technical one. It was psychological. Mead had to work with what he calls "audience in-head memory," where people only believe in something new if it resonates with what they already know.

He worked with that memory partly by making sure every vehicle we saw matched up with the world as a whole, explaining, "For instance, you'd start with the air pollution, and you'd say, 'If that's true, then they would probably have to have bigger air conditioning units.' ... More congested traffic, and you get bigger bumpers." They're all familiar ideas applied in an unconventional way. The same is true for how the vehicles match their characters — J.F. Sebastian the "tinkerer" has a van that's consciously designed to look like he pieced it together himself. Maybe the audience doesn't consciously take any of this in, but it all paints a vivid and convincing picture.

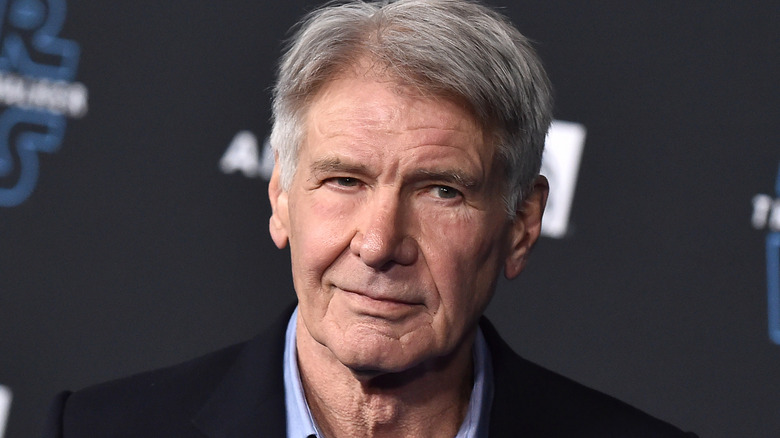

For years, Harrison Ford didn't want to talk about it

Making "Blade Runner" left Harrison Ford miserable. According to Vanity Fair, he wasn't alone in that. The production's continual night shoots were exhausting, and Ridley Scott, who wasn't used to opinionated American film crews, had a talent for rubbing everyone the wrong way. But Ford had an extra complaint. He believed very strongly that Deckard shouldn't be a replicant — "I felt that the audience needed to have someone on-screen that they could emotionally relate to as though they were a human being," he told Vanity Fair — and Scott kept slipping in subtle clues to undermine this. It was a major — and majorly irritating — artistic standoff, and neither one of them could let it go.

The film was also a sore spot for a while because it initially flopped. In hindsight, we can certainly see that it didn't hurt Ford's career, but it must've felt like it at the time. GQ writer Chris Heath noted, "If you read old articles about Harrison Ford, it's jarring to realize that for a while, 'Blade Runner' was included on lists of films that were considered misbegotten attempts by Ford to extend his reach beyond his 'Star Wars' and Indiana Jones franchises."

All in all, we can see why it all left Ford pretty sour, but we're glad that the film's lasting cultural legacy has brought him around on it. He and Scott mended fences, and Ford returned for "Blade Runner 2049," which Scott executive produced.

The film is haunted by The Shining

"Blade Runner" was such a distinctive, ambiguous, and ambitious film that it was, right from the start, in danger of being a flop. So — guided by early test screenings — Ridley Scott decided to inject a little more optimism into the ending. Maybe that would leave audiences a little more satisfied.

The 1982 release, accordingly, featured Deckard and Rachael making their getaway into the mountains, transitioning from the noir cityscape to a kind of idyllic untamed nature where it's possible they can find some kind of peace. But, as Open Culture explains, most of the footage they captured at Big Bear Lake was marred by bad weather. When you're desperately trying to inject a little more hope into your ending, you know what you don't want? Heavy, ominous clouds.

Luckily, Scott remembered the famous opening of Stanley Kubrick's "The Shining," where the camera glides over the mountains to follow the Torrances' car. In context, it's unsettling. Out of context, it's gorgeous. And while Kubrick didn't want to turn over any shots he'd actually used, he was fine with supplying Scott with his outtakes. It's a clever solution ... provided the audience doesn't know about the substitution. No one wants to think that Deckard and Rachael are inadvertently fleeing towards the Overlook Hotel.

Philip K. Dick hated Blade Runner ... until he didn't

Philip K. Dick and "Blade Runner" got off to a bad start. In an interview with The Twilight Zone Magazine, Dick explained that his dealings with Hollywood had left a bad taste in his mouth. He didn't trust the studio, and he didn't like the "Blade Runner" script. He thought Hampton Fancher's original screenplay "cleaned [the] book up of all of the subtleties and of the meaning," and it upset him to feel like his work was being stripped of its real substance.

Seeing a promo of the movie's special effects turned things around. The visuals boggled him. "I recognized it immediately. It was my own interior world. They caught it perfectly." Ironically, this was exactly the change of heart he'd been worried he would have. Beforehand, his agent had urged him to go see the remarkable sets, and Dick had refused, saying, "If the sets are that good, maybe I'll go up there and fall into the mode that exists now in science fiction, where the special effects and the sets are everything." Well, he didn't go that far. But the sets were good, so they prompted him to ask for a copy of the new screenplay. And the adjustments won him over completely.

Unfortunately, as Screen Crush points out, Dick died a few months before the movie's release. He was never able to see it in full, but we're glad it still wound up giving him some joy.

The movie came out at the worst possible time

We're all used to the story of the classic film that bombs at the box office and only picks up its true audience later on. It's happened before, and it'll happen again. And to be fair, the original cut of "Blade Runner" was burdened with lackluster voiceovers and a tacked-on happy ending. If you prefer the more ambiguous later editions, you might understand why theatergoers in 1982 mostly gave this one a miss.

But they also gave it a miss because it opened on June 25, 1982, and June 1982 was almost hilariously swamped with competing sci-fi features, nearly all of which have proved memorable in their own right. As IndieWire explains, "Blade Runner" — already burdened with lackluster reviews — was coming into theaters that were already packed for showings of "E.T." (released on June 11) and "Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan" (released on June 4). And even audiences who wanted darker fare could have flocked to "Poltergeist" (in its fourth week) or John Carpenter's superbly chilly "The Thing," which opened directly opposite "Blade Runner" (and also suffered a little from the competition). It was a month jam-packed with destined classics, and plenty of audiences understandably opted for the more familiar and comforting entertainment of Spielberg and "Star Trek."

Later on, luckily, the movies weren't all pitted against each other, leaving people with plenty of time to discover the greatness they'd initially missed out on.

There's no one true Blade Runner

When you want to watch "Blade Runner," you have to make a choice – which "Blade Runner," exactly? The Verge had a roundtable to break it all down, and as it turns out, there are eight versions of "Blade Runner" that you could've plausibly seen. And these aren't as buried as the original versions of "Star Wars" either. You can still get your hands on several older versions of "Blade Runner," especially if you shell out for the Collector's Edition DVDs.

But for most fans, it comes down to a battle between the original U.S. theatrical cut and Ridley Scott's Final Cut from 2007. Both have their merits. For example, the original is the version that cemented the movie's place in history. No one would've ever cared about the Final Cut if they hadn't already been hooked by the original. It's also not like the Final Cut represents some kind of pristine artistic purity. After all, it's not just a cut free of studio interference — it contains out-and-out reshoots. As The Verge puts it, it's "the work of a nearly 70-year-old filmmaker second-guessing his 40-something self." On the other hand ... that 70-year-old filmmaker knows what he's doing. The Final Cut is a masterpiece of ambiguity, with all the original virtues of the film sharpened and polished. You lose the clunky narration, and you get a much more convincing, haunting ending.

There's no wrong answer here, and both versions — like humans and replicants — are equally real.