Is This The Best Horror Movie Based On A True Story?

Fans of the genre know all too well that one can take all but the most absurd of horror films and — with a bit of elbow grease and very particular plot analysis — eventually hunt down a real-life occurrence that bears an eerie resemblance to the narrative in question. Horrifying things happen, or are believed to have happened, in real life all the time, so it's not surprising that one of the oldest genres in entertainment (via Flavorwire) would take its lead from reality.

The efficacy of horror, in fact, relies on our belief that it is real, that it could happen, and that, scariest of all, it could happen to us. But this requisite relationship with reality notwithstanding, there are certain horror films that are very literally and directly (as opposed to allegorically or metaphorically) inspired by real events. Some of the most well-known of these films are also among the most renowned horror films ever made, including "The Exorcist," (via the Denver Post), "The Conjuring" (via USA Today), and "Poltergeist" (via Nerdist), to name a few.

But amongst all these big screens takes on "IRL" traumas, there's one that just may outshine them all, if for no other reason than the fact that its central horror is the most universally terrifying — and timelessly relevant — of all.

Psycho hit a nerve with audiences

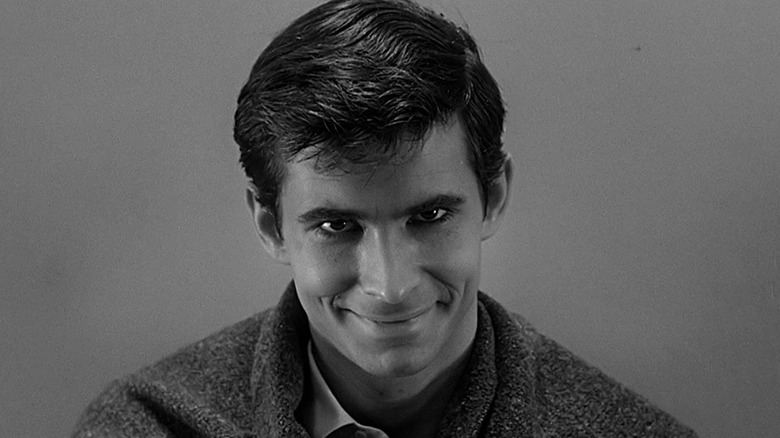

Few (known) serial killers in America's history have inspired as many characters as the chilling mid-century Midwesterner Ed Gein, the Wisconsinite who inspired the Robert Bloch novel off of which Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" was based. In addition to inspiring the infamous Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) in 1960's "Psycho," Gein informed the likes of Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine) in "Silence of the Lambs," Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) in "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre," and Bloody Face (Zachary Quinto) in "American Horror Story: Asylum." Gein was a mild-mannered loner who'd grown up with an absent and alcoholic father and a controlling mother who, in her religious fanaticism, frequently preached against "the sins of lust and carnal desire." After his mother died, Gein's unstable psyche unraveled, and he began murdering townspeople and holding on to their various body parts as decor and souvenirs, all while posing as a quiet and sympathetic handyman (via Biography).

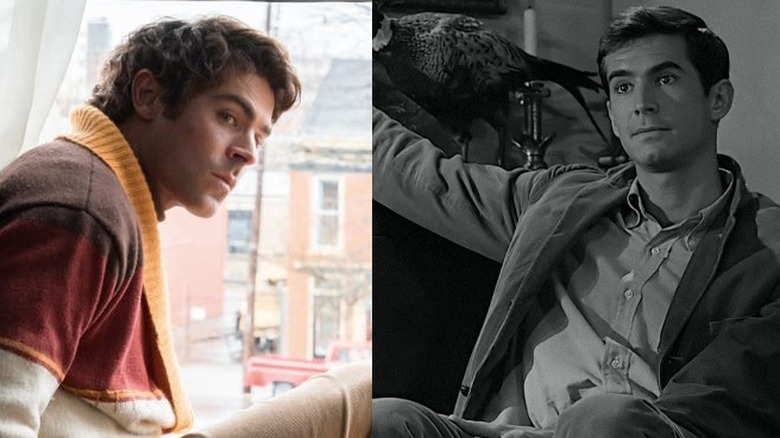

That should all sound vaguely familiar not simply because it's the basis for so many fictional killers, but because it's a background and psychological makeup found in (or, at least, often said to be found in) many real-life serial killers. (See: Every episode of Netflix's "Mindhunter.") With "Psycho," Hitchock introduced audiences to an all-new kind of monster — one that was all the more terrifying for his ability to fit in. Sure, Norman was a little odd, but the late Anthony Perkins was undeniably attractive, so much so that at times in the film, he appears more like a love interest than a suspicious figure. He isn't simply dark — he's tall, dark, and handsome, and therein lies the cognitive dissonance that allows so many murderers to function in society, with horrific consequences.

Psycho spoke to society's relationship with fear

"Psycho" had audiences on Norman's side long after his unsettling hobbies begin to reveal themselves, because — until the twist ending — viewers are led to believe that his evil, domineering mother is still alive, and therefore responsible for everything. By revealing that Norman was simply acting as his mother all along, talking to himself when we're led to believe he's talking to his mom, Hitchcock adds another layer of uncomfortable truth to his narrative. That is, that these mild-mannered, soft-spoken, and attractive killers will continue to lash out long after any supposed "catalyst" has been removed from the equation. (All of which, of course, makes them even harder to spot.)

Of Ted Bundy (a killer whom directors love to romanticize and glorify), forensic psychologist Helen Morrison wrote, "He looked like the boy next door, and that is frightening because if the boy next door is a serial killer, it means anyone is potentially a victim," as quoted by BBC. In "Psycho," Hitchcock forced audiences to face this unsettling reality for the first time on the big screen and drove home the idea that none of us is safe — not even, as Janet Leigh's Marion would learn, in our own shower. Hitchcock's most terrifying monster isn't a creature from the black lagoon, a supernatural demon from hell, or some ethereal, malevolent spirit. He is not only flesh and blood, he's right around the corner, yet entirely invisible.

Hitchcock's Psycho is still all too real

Clearly, the highly-acclaimed "Psycho" resonated with its 1960s audience: prior to its release, a horror film taking home four Oscar nominations was both exceptionally rare and based largely on having a theatrical pedigree (via Rolling Stone). But what makes Alfred Hitchcock's masterpiece stand the test of time isn't just his distinctive cinematography or uncanny ability to draw out tension to its absolute breaking point. (Though to be fair, both those things help.) Ultimately, what sets "Psycho" apart in terms of "based on a true story" filmmaking is that it's somehow — simultaneously — wholly of its time, eerily prophetic, and eternally, contemporarily relevant, no matter where you place it in the timeline of human history. After all, the notion that the "real monster" is hiding right in front of you — the said monster is even (in some cases) your own neighbor — is at the very heart of what drove repeated bursts of witch trials around the known world for centuries.

While ghosts, goblins, and demons have always held a special place in our nightmares, it's those horrors we certainly know are real that scare us most of all. If it didn't invent this approach to horror, "Psycho" was certainly the first major motion picture to employ it. Now, over six decades later, with the success of series like "American Horror Story" and continued celebration of psychological thrillers like "Silence of the Lambs" and "Get Out," it seems the "humans as the real monsters" horror moral is every bit as fascinating and bone-chilling as it was when Hitchcock first tapped into it.

"The Exorcist" may have taken home more awards and garnered a good deal more press (via IMDb), but it's Norman Bates — not some unfathomable demon from hell — who arguably remains the scariest monster ever to be cobbled together from the sordid remains of reality.