Why Star Wars Fans Almost Never Got To See The Film

Face it: Star Wars shouldn't have worked. It was a science fiction fairy tale made when most of Hollywood was cranking out gritty, character-driven dramas like The Godfather, Chinatown, Rocky, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. It starred a handful of unknown actors (and Sir Alec Guinness) and a man in a fur suit. It begins with 20 minutes of robots wandering through a desert. Its main villain is a fully-fledged space wizard.

That sounds like a disaster, not the beginning of a multi-billion dollar franchise. Yet, despite all odds, Star Wars didn't just clean up at the box office, it literally reinvented the entire Hollywood machine. Without Star Wars, we probably wouldn't have Indiana Jones, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the Harry Potter films, or, y'know, the ten (and counting) sequels, prequels, and spinoffs that have debuted or are currently in development.

And it came so close to never happening...

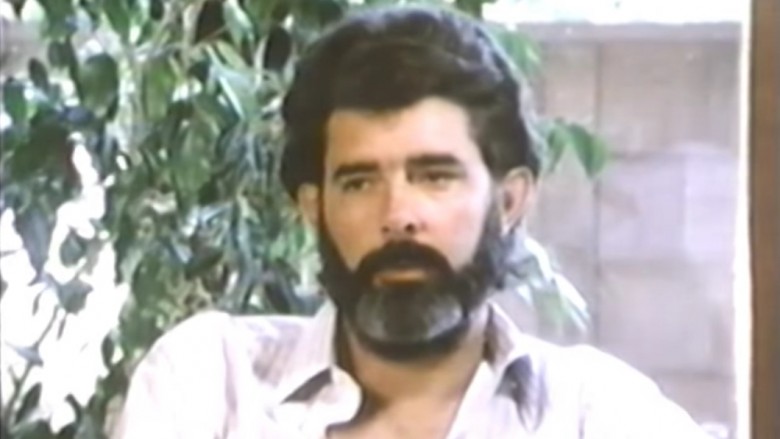

George Lucas wanted to make Flash Gordon, not Star Wars

Star Wars didn't spring fully-formed from George Lucas' head. In fact, if Lucas had his way, he would've made an entirely different movie. As a child, Lucas loved the old Flash Gordon serials that played before movie matinees, and later re-aired on television. After Lucas' debut film, the cold and lifeless science fiction thriller THX 1138, failed to excite audiences and critics, Lucas wanted to make something that showed off his more human side. Flash Gordon, which mixed high-stakes adventures with highly personal stories, seemed like a perfect fit.

Lucas just had to get the rights, and fortunately for the future of Star Wars, that was easier said than done. In 1971, while raising money for American Graffiti, Lucas and his friend, Francis Ford Coppola (the guy who would go on to turn Mario Puzo's pulpy thriller The Godfather into one of the most important films of all time) stopped by King Features Syndicate, which published Alex Raymond's original Flash Gordon comic strip and owned the rights to the character.

The reasons why Lucas and King didn't reach an agreement is unclear. Lucas says that King wanted Italian director Federico Fellini to helm the project, and demanded 80 percent of the film's gross. Star Wars producer Gary Kurtz recalls, "They weren't adverse to discussing it, but their restrictions were so draconian that we realized right away that it wasn't really a great prospect at the time." Either way, a deal didn't happen.

That didn't stop Lucas. As Coppola recalls, after Lucas returned from his meeting with King, "[George] was very depressed because he had just come back and they wouldn't sell him Flash Gordon. And he says, 'Well, I'll just invent my own.'" If the deal had gone through Flash would've hit the big screen three years earlier than he did, and Luke, Leia, Han, and the rest of the gang wouldn't exist.

Everyone encouraged Lucas to make something more like American Graffiti

THX 1138 was a flop, but Lucas' second film, American Graffiti, wasn't. American Graffiti, a nostalgic comedy-drama set in 1962 starring Richard Dreyfus and Happy Days lead (and later, Oscar-winning director and Arrested Development narrator) Ron Howard, earned $55 million on a $1.27 million budget, making it the second-most successful film in Universal Pictures' history at the time.

As you can imagine, Universal executives were delighted, and they wanted more. Lucas, however, had his heart set on Star Wars. While the two films share similar themes — both American Graffiti and the first Star Wars films are coming-of-age stories at heart — in terms of aesthetics and genre, they're very, very different. When Lucas submitted a 12-page outline for Star Wars, Universal balked. "I've always been an outsider to the Hollywood types," Lucas said while doing press for Star Wars. "They think I do weirdo films."

Unsurprisingly, many of Lucas' peers — who'd go on to make some of the best dramas of the '70s — agreed with Universal, and encouraged Lucas to make more films that were grounded and serious. If Lucas had listened, things would've been very different.

Science fiction wasn't popular

Universal isn't the only studio that passed on Star Wars. Originally, Lucas signed a deal to make two films with United Artists. Ultimately, United Artists declined both. Lucas and United Artists disagreed about American Graffiti's screenplay (the film's proposed soundtrack was also considered prohibitively expensive) and production moved to Universal. As for Star Wars, well, according to executives science fiction just didn't sell.

Universal and Disney passed on Star Wars for the exact same reason. They weren't necessarily wrong, either. Star Wars producer Gary Kurtz claims that Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey took seven years to turn a profit, and notes that the last big space opera, Forbidden Planet, was nearly 20 years old by the time that he and Lucas pitched Star Wars. Films like The Andromeda Strain were only modest successes, while the long-running sci-fi franchises like Planet of The Apes were starting to falter.

While Lucas tried to explain that Star Wars isn't science fiction — "Star Wars is a fantasy, much closer to the Brothers Grimm than it is to 2001," he says — ultimately, it wasn't Star Wars that got the attention of 20th Century Fox president Alan Ladd, Jr. It was Lucas himself. According to Lucas, Ladd said, "I don't understand this, but I loved American Graffiti, and whatever you do is okay with me." In 1973, Lucas signed a deal to write and direct Star Wars for Fox, and promptly got to work.

The production didn't have enough money

Here's one of Star Wars' biggest secrets: it was not an expensive film. While Star Wars (along with Jaws, which cost even less to make) established the template for the expensive Hollywood blockbuster, its budget was tiny, even by 1976's standards. That's one of the reasons why the movie got made. According to producer Gary Kurtz, he and Lucas pitched Star Wars as a cheap Roger Corman-style adventure flick. After all, Lucas made American Graffiti for almost nothing, and according to Kurtz "...there's a hard-core science fiction audience...even if no one came to see it except those science fiction fans, by the time it got to video it would have made its money back."

Fox gave Lucas and his crew $8 million, which Kurtz estimates was about three to four times less than a big-budget action movie with lots of special effects. Unfortunately, that wasn't quite enough. When Lucas and Kurtz asked for more, Fox shut down pre-production and forced the team to come up with a new budget.

For about two weeks, Kurtz, Lucas, and the rest didn't do much more than recalculate the final budget, which came out to about $10 million. That was still low enough to proceed, although Lucas was forced to scrap a number of scenes — including Han Solo's confrontation with Jabba the Hutt — in order to make the budget work (ultimately, the film would cost about $11 million, thanks to an expensive post-production process and some second unit reshoots).

On-location shooting was a disaster

Tatooine, Luke Skywalker's home planet, was originally supposed to be a jungle, but Lucas changed it to a desert planet after a location scout in the Philippines irritated his skin (in tribute, the now non-canonical Star Wars Expanded Universe said that Tatooine used to be covered in trees, but an ancient superweapon transformed it into a dusty wasteland). That might've been a mistake. While Tatooine's twin suns setting over the dunes is one of the most iconic images in a franchise full of them, Tunisia isn't the most hospitable environment for filmmaking, and the production fell behind immediately.

Allegedly, the sand didn't mix well with the cameras, damaging lots of expensive equipment. Windstorms ravaged the sets, which were imported from England. R2-D2's controls didn't work particularly well, either, as the sand interfered with the remote's radio signals — allegedly, the crew spent an entire day getting a single shot of the droid moving a couple of feet.

And then there was the weather. On the second day of shooting, a freak rainstorm — the first winter rain that the area had gotten in 50 years — made filming practically impossible. Gilbert Taylor, Star Wars' cinematographer, says that Lucas tried to work through the inclement weather, but that the results were "a gray mess, and the robots were just a blur."

Ironically, a freak storm hit the Star Wars sets again when Lucas returned to Tunisia to film the prequel trilogy. "It was as if the storm had hidden away for twenty years, just waiting to come back," Lucas said, although the second time around he had a massive crew and the Tunisian military to help clear things up.

Nobody took Star Wars seriously

For George Lucas, Star Wars was a labor of love. That wasn't not true for anybody else. The British crew at Elstree Studios, where production designer John Barry built the massive sets needed to bring Tatooine, the Death Star, and the Millennium Falcon to life, thought that the film was ridiculous, and didn't hesitate to let people know. Aside from Alan Ladd, none of the Fox executives knew what to make of the project. Many of the cast members thought that the movie would tank. Harrison Ford still doesn't get it.

Lucas' demeanor didn't endear him to the crew, either. Shy and reclusive, Lucas admits that he doesn't particularly like working with others. "I ended up having to be nice to everybody, which is hard when you don't like a lot of people," he says, which is a problem given film's collaborative nature. According to Gary Kurtz, "The crew expected a little more gregariousness from the director, and they kind of resented it, that it wasn't that way."

Actors had a particularly difficult time. Not only were they doing most of their work in front of blue screens, using weapons that didn't work and interacting with objects they couldn't see, but Lucas only gave them limited directions, which was often more frustrating than helpful. Considering the combination of the hectic schedule, the production problems, and the cast and crew's general discontentment, it's amazing that Star Wars turned out any good at all.

Delays almost doomed the project

Thanks to the problems in Tunisia, Star Wars was behind schedule by the time that the crew moved to England. Unfortunately, things didn't get much better. Thanks to British union rules, filming couldn't start earlier than 8:30 a.m., had to stop at 5:30 p.m. (unless Lucas was right in the middle of shooting a scene — in that case, he could film for an extra 15 minutes), and included a one-hour lunch break and two brief interludes for tea.

It didn't help that Lucas was still tweaking the script while filming — apparently, he couldn't decide whether Luke's last name should be Skywalker or Starkiller — or that Lucas couldn't stop micromanaging every little detail, or that Star Wars' original editor, John Jympson, didn't grok the documentary-like aesthetic that Lucas was aiming for. Filming began in March 1976. By July, Lucas was 15 days behind schedule. Something had to be done.

Alan Ladd Jr., who was pretty much Star Wars' only champion at Fox, issued an ultimatum: Lucas had to finish the film in a week, or Fox was going to pull the plug. Lucas split the production into three parts — one led by him, one led by Kurtz, and one led by production manager Robert Watts — and spent his days bicycling between sound stages. Lucas' close friend Steven Spielberg asked to oversee one of the units, but thanks to the duo's growing rivalry, Lucas shut him down.

The groundbreaking special effects almost didn't happen

Star Wars set a new standard for visual effects when it debuted in 1977, but Industrial Light and Magic's first feature was almost its last. During filming, John Dykstra and the rest of the ILM team provided Lucas with footage that was supposed to be projected onto the set during filming, but was often cheap-looking and out of focus, forcing the crew to use blue screens — and, of course, pushing the film even further behind schedule. When principal photography ended and Lucas returned to Hollywood, he learned that the ILM team had blown through over half of their $2 million budget and only completed three shots — and none of those were usable.

According to Kurtz, it wasn't that the visual effects team was lazy, or that they weren't doing their best. They were simply unorganized. For example, while most of the crew was filming in England the ILM team would only work on one shot at a time. They'd set up the scene, capture the footage, then wait to have it developed before dismantling the rig and moving on to the next shot. While that made it easier to reshoot footage that didn't turn out well the first time, it also made for a very slow production process.

Ultimately, Kurtz stepped in and streamlined the process, while Lucas helped by editing together dogfights from old war films in order to help ILM's staff visualize Star Wars' space battles. At the same time, Ladd scrounged together a little bit more money (the visual effects department ended up going over-budget by about 35 percent), an outside company was contracted to create convincing explosions, and the visual effects artists worked day and night to finish the movie on time, completing an average of a shot a day.

The whole process almost killed George Lucas

Even when things are going well, making movies isn't easy, and Star Wars' production did not go well. While filming at Elstree, Lucas' health took a dive, and he almost didn't recover. Thanks to the constant barrage of problems, Lucas became depressed. He didn't like England, particularly the food. He didn't get along with the crew. His house was broken into, and his television was stolen. He developed a cough and a foot infection, and could barely get out of bed. During the final days of filming, he lost his voice.

Things got worse when he got home. After learning how far behind ILM had fallen while the rest of the crew was overseas, Lucas went to the hospital for chest pains. He thought he was having a heart attack. Instead, doctors diagnosed Lucas with hypertension and exhaustion and ordered him to take things easy.

But he couldn't. Star Wars wasn't finished, and Lucas had to push on.

The studio almost buried the movie

While an early screening for studio executives went well, Fox wasn't sure how to sell Star Wars to the public — so, they didn't. Instead, the studio put its marketing muscle behind The Other Side of Midnight, a Charles Jarrott (Mary, Queen of the Scots) film starring Marie-France Pisier and Susan Sarandon. Unlike Star Wars, which was an unknown property, The Other Side of Midnight was based on a best-selling novel, and had a built-in audience.

By contrast, theater owners thought that Star Wars was a "kiddie movie" and didn't want to screen it. In order to boost circulation, Fox forced theater chains that wanted The Other Side of Midnight to book Star Wars as well. In the end, the film opened on 32 screens around the country on May 25, 1977. An extra 11 started screening the film on May 26 and May 27. When Fox contacted Larry Gleason, president of Mann Theaters, about screening Star Wars at Hollywood's iconic Chinese Theater, they promised that the movie would be finished after two weeks.

Of course, they were wrong. As Star Wars broke record after record for both attendance and box office returns, Fox expanded into as many markets as possible. By September, Star Wars was in 1,100 theaters — an unheard of number at the time — and its first theatrical run lasted for over a year. On August 3, 1977, thousands of fans gathered outside Mann's Chinese Theater as R2-D2 and C-3PO dipped their feet in cement outside, adding their footprints to those of screen legends like John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, and Charlton Heston. Star Wars' second stay at Mann's Chinese — the first time in history that movie returned to the location during its first run — lasted until June 1978.

By then, it was clear: despite the odds, Star Wars was a hit, and Hollywood would never be the same.