The Ending Of Synecdoche, New York Explained

Charlie Kaufman doesn't bunt. He has never aimed for a bloop single. His most famous scripts –– "Being John Malkovich," "Adaptation," "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" –– are all big swings, ones where the screenwriter is aiming to hit the ball as far as he possibly can, tackling big-picture subject matter like the creative process and the mind and its relationship to reality.

So when it came time for Kaufman to make his directorial debut, he wasn't going to rein in his ambitions. Instead, he set his sights on his most formidable project yet: a sprawling pastiche of life itself about a struggling artist's attempt to create a sprawling pastiche of life itself, 2008's "Synecdoche, New York."

Critics were divided on the movie, but the ones who liked it really did. Christopher Orr of The Atlantic called it "a huge film about puny sentiments, an anti-heroic epic of failure, remorse, alienation, and self-pity," and he meant it in the best possible way. "The film is either a masterpiece or a massively dysfunctional act of self-indulgence and self-laceration," wrote The Guardian's Peter Bradshaw in a five-star review. "It has brilliance, either way: surreal, utterly distinctive, witty, gloomy in the manner that his fans will recognise and adore." Roger Ebert named it his best movie of the 2000s, saying "Charlie Kaufman understands how I live my life, and I suppose his own, and I suspect most of us." So what is he trying to say anyway?

Synecdoche, New York is about an attempt to capture life in a bottle

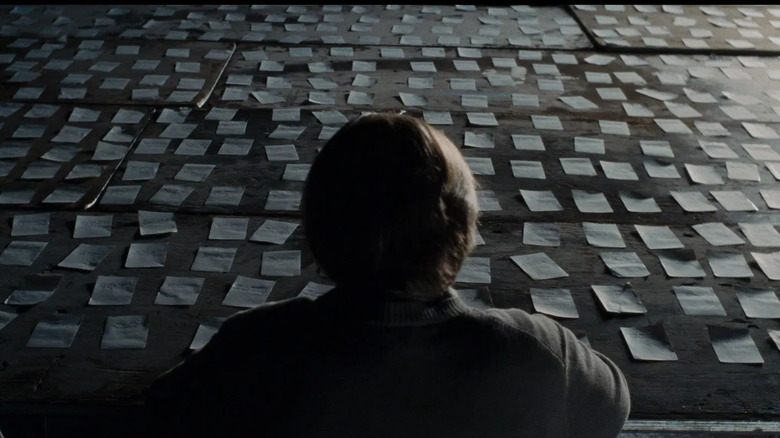

The film follows theater director Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman), who's presented early on as struggling with both his health and his relationships –– he sustains a head injury from a plumbing accident early on and his first wife, Adele (Catherine Keener), soon leaves for Berlin with their young daughter. When he's unexpectedly awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, Caden decides to use it as God intended: buying a giant building in New York City and staging a never-ending exploration of the banality of everyday life that's meant to be his masterpiece. He builds a mockup of the city in the space and populates it with hired actors who go about their lives as directed by him.

Getting the play right, however, is a process that takes years. The world on stage and the world outside begins to blur. The events take on a surrealist, dream-like logic. The stage itself expands to overtake the city. Caden hires his own stalker (Tom Noonan) to play the role of himself, and another actor (Daniel London) to portray his stalker. A meta-play inside the play becomes part of the staging. Eventually, he gives his directorial role to someone else (Dianne Wiest) and retreats to live out his life by taking a small role, even as his cast dies out and his massive set falls into disrepair, though at that point, who can say whether it's the world on stage or the actual world that's collapsing.

What is Synecdoche, New York saying about art?

First, a quick 10th grade English lesson. Synecdoche, you may remember, is a literary device wherein the part is used to represent the whole or vice versa. When someone says "boots on the ground" to refer to the deployment of troops, that's synecdoche. There are thousands of these baked into the language that you don't even notice anymore; your brain ticks right over the literal meaning because it knows what it stands for.

This is part of what art is meant to do. Films, plays, paintings, and even screenplays reflect some part of the world and the experience of being alive back to the people living in it. The Great American Novel, if you still believe in such a thing, is supposed to capture the breadth and depth of the American experience, which is probably why it has proven so difficult to find one.

In "Synecdoche, New York," Caden struggles against the impossibility of this. There is always something missing, and the desire to find what that is and represent it consumes him. "Caden's work is so literal," Kaufman told Twitch Film in an interview. "The only way he can reflect reality in his mind is by imitating it full-size." It ends up being a kind of inverted mirror of "The Truman Show." Instead of trying to escape this fake simulated reality that's been built for him, Caden tries to construct a simulated reality that is somehow fundamentally true.

What is Synecdoche, New York saying about life?

As Caden pours himself into the work, he loses track of his own life. The line between life and art, fact and fiction, blurs and eventually disappears. The film jumps across years in ways that seem to indicate that he hasn't noticed how much time has elapsed. He passes off his roles to other people, freeing himself of some of the responsibility of his life, but each of those changes chips away at his own life and alters his perception of himself and the part he plays. In the end, there is no world but the one he has made.

One way to look at it is as time passes, we narrow down our vision of what life is, more rigidly defining who we are. We pick the roles we want to play, the things we want to pay attention to, and even as the knowledge of the world around us grows and it seems to get bigger, our part in it becomes more narrow, more inflexible. And that's happening to everyone. They pick their story and burrow deeper into it, and no matter what we do, we can't really understand them, can't see from their perspective. We live in our life-sized diorama of the world, while other people do the same in theirs, and there is something unbridgeable about this gap.

Caden tries, or at least he thinks he does. "None of those people is an extra. They're all the leads of their own stories," he says. Is that knowledge enough to reach a true connection with other people? As the actor playing him tells him, "I've watched you forever, Caden, but you've never really looked at anyone other than yourself."

What is Synecdoche, New York saying about death?

So, if the film is about life itself, then what is its ending? Death, obviously. Death permeates the story. Caden worries that he's dying from the beginning. He obsesses over the death of his father and experiences the death of his daughter over the course of the film's murky timeline. "I will be dying and so will you, and so will everyone here," Caden tells his cast at one point. "That's what I want to explore. We're all hurtling towards death, yet here we are for the moment, alive."

The film's final scene shows an elderly, exhausted Caden, moving through the lonely ruins of his making until he finally finds a place to rest his head. And yet even in this life, death comes as a running out of time. His last lines are, "I know what to do with this play now. I have an idea," but he's cut off by the voice of the play's new director in his ear (or in his head), giving him his final instructions. "Die," she tells him.

"The result is a film that is less philosophical, or even psychological, than neurological in impact," wrote Orr in his Atlantic review. "It doesn't make an argument, it evokes a mood, a broad sensation of regret and exhaustion." That's certainly one way to look at life, at all things we missed and will miss, at its essential unknowability, and at how we're all going to run out of time in the end, whether we like it or not.

"Everything is more complicated than you think," one character says during a (staged) funeral eulogy. "Synecdoche, New York," like life, certainly is.