The Velvet Underground Review: Linger On

In the realm of music documentaries, there seems to be two kinds: deep dives into bands everybody knows, or arguments for obscure groups worthy of more attention. Which is why Todd Haynes' "The Velvet Underground" (now on Apple+) is a compelling must-watch from the first frame: This is a band many know, but few know; it's a band that gets tons of recognition, but few understand why.

To his credit, Haynes chooses to unfurl his tale as if the documentary itself was a Velvet Underground creation: at times it sings, at others it becomes an endurance test; it frequently feels like an exercise in stream-of-consciousness, but look closer and you'll see a confident, magnificently orchestrated blueprint; there is an infectious melody to be found, but it stubbornly refuses to give you things the easy way.

The only comparison that feels anywhere in the same ballpark, as far as tone and format are concerned, might be the 2015 Brett Morgen film "Cobain: Montage of Heck." It similarly blends mixed media, interviews with those who were there, and personal materials to give you a sense of the musical act, rather than a retelling of their public persona. Like "Montage," "The Velvet Underground" is driven by the families and/or surviving members (John Cale and Maureen Tucker, both still quite feisty, give great new interviews), and much as "Montage" heavily featured Kurt Cobain's home movies, "Velvet" utilizes so much Andy Warhol-shot footage that it feels like he should be credited as a posthumous co-director.

The most notable creative flourish, right off the bat, is that you don't hear any Velvet Underground songs until over 45 minutes into the film. Can you imagine a documentary on the Beatles, Rolling Stones or Bruce Springsteen ever attempting such a thing? Instead, Haynes relies heavily on Warhol's single-shot, silent experimental films "Sleep" and "Empire," but even more on his "Screen Test" films, which often consisted of several minutes of the subject sitting in front of the camera, simply existing. Although Warhol was known for being prophetic, even he could never have imagined how useful this footage would be nearly 50 years later to a filmmaker with a fondness for split screens.

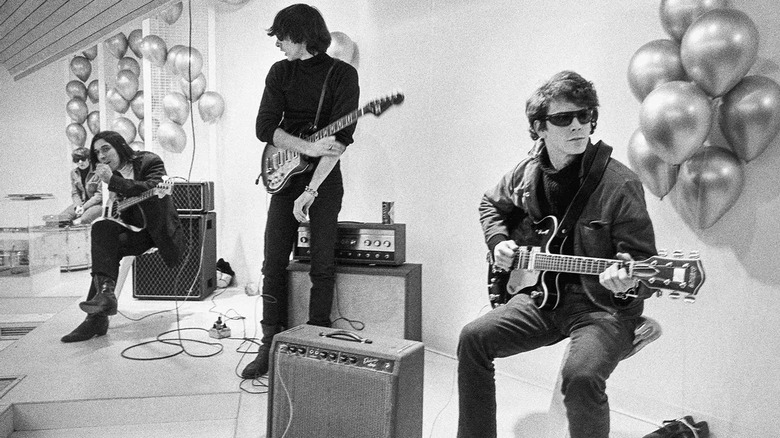

So, we meet the Velvets — Lou Reed, Cale, Sterling Morrison and Tucker — with sound working alongside their steady faces on one side of the screen, experimental or period images often counterbalancing the other side and driving the narrative forward. It's an incredibly effective way of introducing each "character" and telling the audience their backstory, before finally bringing them together. By the time "The Velvet Underground" finally does, and their music is finally unleashed on our ears, it feels like the first action scene in a superhero team-up movie. In their own twisted, bizarre way, each of these people were born to do this — and the final result is something none of them could have achieved with anyone else, under any circumstances other than Andy Warhol's freewheeling Factory.

"In most collaborations ... you put two and two together and get seven," explains Cale, the classically trained Welsh composer whose avant-garde leanings paired brilliantly with Reed's desire to be a rock 'n' roll star with the heart of a poet. "That weirdness, it shouldn't have existed in this space. And there was always a standard that was set for how to be elegant and how to be brutal."

Between thought and expression lies a lifetime

The Velvet Underground have so many elements to their rarely-told story that are absolutely fascinating. One is the existence of Nico, a statuesque German singer and model whose husky, icy voice left much to be desired — yet, upon her arrival in America, Warhol and collaborator Paul Morrissey paired her with the Velvets, much to their initial chagrin. The group wore black; she'd wear white. One critic said her singing "sounds something like a cello getting up in the morning." Andy Warhol wanted her to perform on stage in a plexiglass box, displayed away from the others.

Meanwhile, Cale was obsessed with "drones," not the flying kind but a mesmerizing, repetitive sound often composed of a single held note. Cale would attend and/or perform shows where a drone would go on for hours, with toneless repetition yielding chaos, calm, and an almost meditative state where some claimed transcendence could be found through its sonic power.

Then there was Reed, who had wanted to be a rock star since high school, possessing an undeniable songwriting talent — and an equally undeniable cruel, anti-collaborative streak. He had appeared in '60s would-be pop groups and partnered with Cale on a would-be dance hit called "The Ostrich" (which Reed's sister Merrill Reed-Weiner delightfully acts out in the doc), but his twisted upbringing and reckless life leanings (drugs, sex, shock therapy, and so much more) gave him a deep, dark well of material to write about that no pop song of the day could handle.

There was also a deep hatred of hippies — the prevailing force in music and counter-culture at the time. "This 'love, peace' crap, we hated that. Get real," recalls Moe Tucker. "Everybody wants to have a peaceful world and not get shot in the head or something, but you cannot change minds by handing a flower to some bozo who wants to shoot you. Do something about it. Don't walk around with your flowers in your hair."

Somehow, as if by miracle, all this was brought together — Cale, Reed, Nico and all the rest — and engineered by Warhol, whose leadership style seemed to consist of keeping the cameras rolling, and holding back enough approval that everyone would work harder to get it from him. And somehow, it worked.

"Andy produced our first record, in the sense that he was there breathing in the studio," recalls Reed, who died in 2011 but is nonetheless present via archival interviews. "But he did more than just that. He made it possible for us to make a record without anybody changing it or anything, because Andy Warhol was there."

You may have heard the classic songs a million times — "Heroin," "Venus in Furs," "I'll Be Your Mirror" — but after "The Velvet Underground" has made you more fully aware of what each person brought to the table, and the incredible ways these different flavors complimented each other, it's like you're hearing them again for the first time.

"You never knew when Lou or John was gonna go off into nowhere land and be playing who-knows-what," explains Tucker, in just one of the amazing quotes in the film. "I felt like my role was to be there so when they were ready to come back, there it is."

If you close the door, the night could last forever

It must be mentioned that Haynes has made an artistic decision here akin to tying one hand behind his back as a filmmaker. There are no critics featured, no historians, no one from Rolling Stone or some other source who can go on and on about that old chestnut: The Velvet Underground didn't sell many albums, but everyone who bought one went out and started a band. As such, the film is light on historical context, relying instead on band-adjacent people (and a few musicians, like Jackson Browne and Jonathan Richman, who both had a link to the Velvets in their early days) to explain the disappointing record sales, bizarre art installation performances, and eventual frustration and dissolution of the band.

"We understood where we were, where everything else was, and how much disdain we had for everything else," Cale said of the band's slow, bitter goodbye. "In the end, unfortunately, it became each of us."

Would it have been nice to have more than an old David Bowie interview to put the band in context? Would this Velvets fan have liked more explorations of the songs ("Pale Blue Eyes" and "All Tomorrow's Parties" are heard but barely discussed; "Here She Comes Now" and "Some Kinda Love" are nowhere to be found), some discussion of the 1992 reunion that yielded the wonderful "Live MCMXCIII" album, and more acknowledgment of Tucker's contributions as a groundbreaking female drummer? Sure, but Haynes' film is a triumph on its own terms — and much like the band's music, this film doesn't contort itself to please any audience.

"I knew that we had a way of doing something in rock and roll that nobody else had done," Cale says at one point, explaining the band's early days of possibility and promise. "And I'd say: 'Hey Lou, nobody's gonna be able to figure out how the hell to do this."

Experimental, temperamental and at times, just plain mental, there will never be a band again like the Velvet Underground — and there probably shouldn't be. Decades later, we're left with the one-of-a-kind songs, the larger-than-life stories, the inspiration that lives on in every band that fearlessly seeks to depict alienation, drug-induced escape, and sonic experimentation mixed with good old rock 'n roll. But at least now, we Velvet Underground fans finally have a proper documentary — one that doesn't so much tell their story as make you feel like you're in the middle of it.