Older Movies With Special Effects That Still Hold Up

Today, special effects often just don't feel very ... well, special. Audiences have become so accustomed to block-busting explosions, planet-piercing laser beams, invincible superheroes and light-speeding spaceships that we've grown inured to visuals that attempt to turn fantasy into reality. This is unfair, of course, to the under-appreciated VFX crews working to the bone to make visual magic happen, but after decades of a Hollywood visual arms race, perfection has become the bare minimum requirement to keep an audience's attention.

Sure, some groundbreaking achievements (like Chris Evans turned scrawny in "Captain America: The First Avenger," or bringing actors back from the dead) get the attention such creativity deserves, but even the slightest misstep in CGI or practical effects risks not only knocking the viewer out of their desired state of immersion, but also an onslaught of online ridicule.

Back in the day, things were very, very different. CGI wasn't widely rolled out until the mid-to-late 1990's, so any film released before that had to get very creative in its world-building. With that in mind, here's a look back on the best special effects of older movies. From the game-changing stop motion of 1933's "King Kong" to the chilling makeup mastery of 1973's "The Exorcist" to the strikingly modern spaceships of "2001: A Space Odyssey," these are older films whose visuals still hold up.

The Ten Commandments (1956)

Some may consider "The Prince of Egypt" to be a superior cinematic adaptation of the Exodus story — which follows God using Moses to free his chosen Hebrew slaves from Egypt — but it's hard to deny that "The Ten Commandments," the Charlton Heston-fronted Biblical thriller, doesn't have impressive acting, writing, and special effects for its era. Back in those days, gorilla suits, clunky robots and a plethora of westerns was as ambitious as effects got. Suddenly, along came this biblical drama with a standout sequence that made jaws drop.

When it comes time for the parting of the Red Sea, as the Israelites reach the water while being chased by vengeful Egyptian warriors, Heston's Moses says "Behold His might hand," and it's go time. Looking back decades later, anyone can tell they're standing in front of a projection screen, with off-camera fans blowing their hair.

But the effect, achieved by filling an enormous tank with water and Jell-o, then simply reversing the footage to give the impression of the water receding, is a crude but charmingly creative solution. Back in those days, visual effects teams lived by the "mother is the necessity of invention" credo — and watching a moving sequence like this, you can't help but wonder whether that was better. After all, if the "Ten Commandments" filmmakers had CGI at their disposal, we can all imagine what the scene would have looked like — and how quickly we'd all have forgotten it.

Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991)

Long considered one of the greatest sequels of all time, the film that elevated the Arnold Schwarzenegger-fronted "Terminator" franchise from cult-classic to summer blockbuster boasted a must-see special effect that had audiences buzzing about. It capitalized on newly-minted CGI abilities to replicate liquid that led to a partnership between Stan Winston and ILM, manifesting itself on screen in a new breed of Terminator: The T-1000, a shapeshifting, liquid metal machine played with icy aplomb by Robert Patrick.

"Computer-generated images are a way of coming up with new effects — particularly after we've been doing traditional effects for 80 years," ILM visual FX supervisor Dennis Muren said of the then-gestating process.

This new terminator could phase through walls, absorb bullets, and shape shift to create metal piercers. It appeared to be the very definition of "unstoppable killing machine," and made Arnold's model look like an old-timey pocket watch by comparison. In jumping on the effect and bringing it to fans, filmmaker James Cameron did everything a sequel should: expand on what made the original work, while bringing new ideas to the table.

But it wasn't just the T-1000 that made the movie. "T2" gave audiences thrilling action sequences with old-school stunts (the truck chase scene is still a masterclass in action filmmaking), an iconic science-fiction script at its narrative peak, and transformed the villain from the first film into arguably the most iconic "hero" of the '90s. All these years later, however, it is still Patrick's T-1000 assassin morphing through walls and jail cell bars that remains front of mind.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

The late '70s and early '80s are considered by some to be a golden age of cinematic science fiction, in large part due to films like "Alien," "Blade Runner," "E.T." and all those Star Wars movies — each instant classics that still shape the way films are conceived, imagined and marketed. One of the era's biggest hits was Steven Spielberg's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," which often takes a backseat to fond remembrances and revisits of its contemporaries, but is no less a sci-fi masterpiece.

Following a blue collar Midwesterner (Richard Dreyfuss) as he unexpectedly acts as a conduit between alien visitors and the human race, the film is brilliantly told — and it also looks fantastic still, decades after it was released.

When the alien mothership descends on a landing site near Devil's Tower in Wyoming, the humans communicate via light and sound, creating a striking, primal contrast to the futuristic sight of the the alien craft. The ship itself is massive, otherworldly, covered in lights, and still mesmerizing to behold all these years later. CGI has been around for several decades now, and no one has created a more iconic space invasion yet.

The Thing (1982)

At his peak, John Carpenter was the untouchable master of cinematic horror. He gave audiences one of the first (and still arguably the greatest) slasher films of all time in "Halloween." Just a few years later, we got an unforgettable, gleefully-unnerving creature feature masterpiece in his remake of "The Thing."

Kurt Russell (who partnered with Carpenter multiple times in the '80s) lead the cast as an Antarctic researcher whose isolated crew was slowly going mad as an extraterrestrial monster hunted down and possessed them one by one. With paranoia reigning supreme, the stage was set for some unnerving practical effects to drive home the squirms.

While the sticky, gooey slime that drenches every shot of the movie's titular extraterrestrial parasite is very much a product of the era, never before or since has that unique style of practical effects been put to such nauseatingly effective use. Rob Bottin, the special makeup effects designer, initially weirded Carpenter out with his insistence that the creature be able to disgustingly morph into anything it touched, thereby harnessing an ability to look like anything.

Nearly ten percent of the film's entire $5 million budget was spent on the groundbreaking creature effects alone. Using a mix of rubber, food products, mechanical parts and chemicals, Bottin created freaky dogs, human heads morphed onto spider legs, chests devouring people's hands and other nightmare fuel. People never mention "The Thing" as a scary Halloween movie — but if you really want to get yourself freaked out in any given October, there is no movie that will leave you more shook.

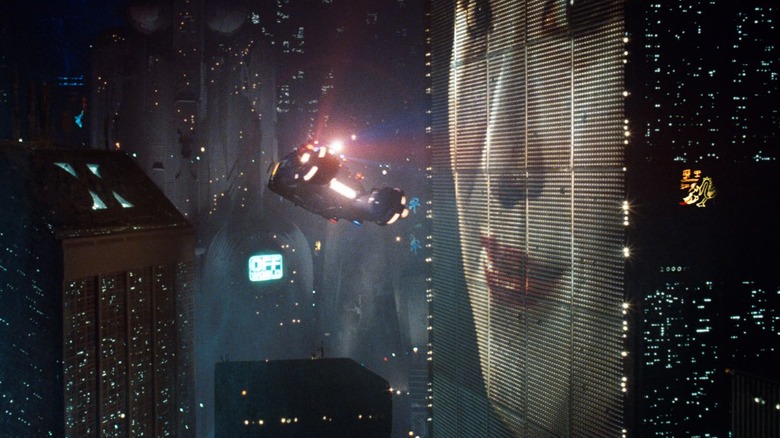

Blade Runner (1982)

"Blade Runner" gave audiences Harrison Ford as Rick Deckard, a man of the titular title whose job it was to "retire" (ie, kill) humanoid "replicants," indistinguishable from humans and considered to be highly dangerous. But the futuristic film would become just as beloved for its storyline as Ridley Scott's vision of the future: global yet localized, cold and rainy yet intimate, all feeling so lived in, so filled with possibility — but threatened by innovation gone wrong.

The special effects, costumes and stuntwork come together to create a depiction of a dystopian, sci-fi Los Angeles with enormous video billboards advertising products, towers spitting fire into the sky, flying police cars, LED umbrellas and transparent raincoats. Many shots were achieved putting different scale models alongside one another, others employed matte paintings or even dollhouse parts. Motion-controlled cameras layered shots upon shots to paint a vivid, lived-in world, while design elements would mix hard-boiled detective elements from the 1930's with futuristic cityscapes. Here was a vision of the future that didn't involve silver suits or laser guns — just an unsettling sense that the world had evolved, and not necessarily for the better.

King Kong (1933)

Like Godzilla, Dracula, Peter Pan, Robin Hood, and more than a handful of superheroes, King Kong has been depicted pretty frequently throughout the history of Hollywood. But still, the loudest and proudest "Kong" outing remains the untouchable 1933 original.

This is the one that first depicted the monster ape fighting T-Rexes and swiping at biplanes from the top of the Empire State Building, with Ann Darrow trapped in his giant leathery palm. One of the most iconic shots in movie history, it got there because of the groundbreaking use of stop motion, miniatures and matte paintings that brought the beast to life.

Visual effects supervisor Willis O'Brien supervised a team that employed glass painting, miniatures, models and mattes to make Skull Island look like a real location; Kong was realized via multiple puppets, men in suits, an enormous mechanical heads and arms, and rear-screen projection that put stop-motion creations behind live-action actors. The end product was a film that blurred fantasy and reality better than any had ever done before.

The process of bringing all this to life was, understandably, painstaking. Exhausted stop motion artists had to work through heavy eyes and dehydration until the scenes were complete, as taking a break would result in immersion-shattering inconsistencies. But it's hard to say the end result wasn't worth it, and then some.

The Exorcist (1973)

How do you convince an audience that is a little girl has the devil inside her? How do you convince them that a battle between the forces of good and evil is unfolding in a nondescript bedroom? And how do you do it without any computer-generated effects at your disposal?

For "The Exorcist," the answer came in a mix of practical effects, creative makeup, editing tricks and some very convincing acting, all bringing to vivid life William Peter Blatty's demon-possession story. Years later, a simple photo of Regan MacNeil's green, scarred, yellow-eyed inhuman face is still more than enough to keep you awake at night.

The same could be said for the infamous "Pazuzu face," which appeared for a handful of brief, unforgettable split seconds throughout the movie. Not to mention the back-breaking harness throws, the pea soup, off-camera gunshots and other trickery employed by director William Friedkin. Many of these techniques are all simple enough, but perhaps nobody had ever wanted to delve quite so deep into such darkness. Perhaps, nobody ever should again.

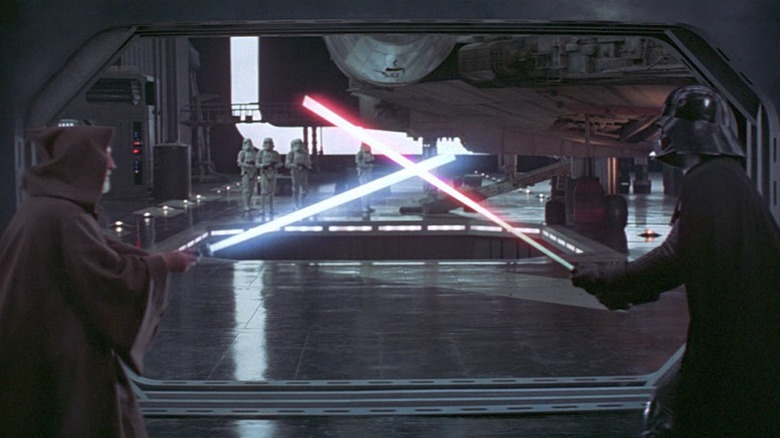

Star Wars (1977)

When it was released, "Star Wars: Episode IV — A New Hope" was simply called "Star Wars," and it was also both a relic of the past and far ahead of its time. It owed much of its outer space battles to old World War II dogfighting footage and swashbuckling adventure serials, but despite a small budget and very limited special effects technology, devised innovative ways to make audiences believe in enormous spaceships, fully-integrated droids, lightspeed space travel and endless space denizens that were instantly cute, endearing and/or fear-inducing.

From the opening shot of the rebel ship fleeing a massive Imperial Star Destroyer, to the droids, to the lightsaber scenes, space dogfights, and destruction of Alderaan and the Death Star, it blew audiences away in 1977. Although any version you see today is inevitably a product of the constant tinkering that has occurred over the last several decades, "A New Hope" remains a permanent touchstone of the visual effects community. It's also enduring proof that movies that get creative and don't stretch existing technology beyond breaking point stand the test of time better than many more contemporary films.

Alien (1979)

Two years after "Star Wars" changed the game, and three years before Ridley Scott released "Blade Runner," he would similarly transform science fiction with another unique reinvention of reality.

"Alien" followed the crew of the Nostromo, a commercial space tug vessel that responded to a distress beacon on a nearby moon — discovering a hulking killing machine that stalked the corridors of the ship and hunted down the crew one by one.

It's a great script, all the actors are on top of their game — but a huge reason "Alien" remains such an effective, mesmerizing, otherworldly spectacle is the visual effects. Designed by HR Giger, who described himself as "responsible for all the fantasy scenery," he designed the different alien monsters, much of the planetary work and elements like the crashed spaceship. His sketches are amazing, which he has said "all emerged out of my own personal visual world, which I call bio-mechanical."

Then there's the Nostromo itself, darker and more economical than those seen in 1968's "2001: A Space Odyssey," but still perfectly modern and believable, like some kind of claustrophobic, interstellar submarine. It's the perfect setting for an outer space haunted house movie.

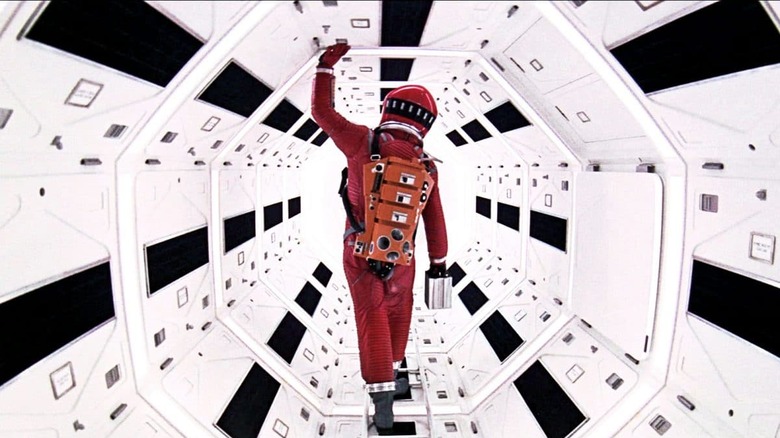

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Stanley Kubrick's unflinching vision of space as a cold, intolerant wasteland of possibility and primality remains every bit the bona fide, game-changing science-fiction classic it was upon release. Its visual effects also hold up, even after multiple viewings, largely because the set pieces and special effects still feel jaw-droppingly modern, considering the fact that movie was released before the actual moon landing.

This was one of many things Kubrick did brilliantly — while films like "2001" and "A Clockwork Orange" may have a few touchstones that date it (record albums, landlines), he largely succeeded in making such films untethered to any specific decade. In many ways, "2001" still feels like the future.

The space suits still look sharp and futuristic, the space ships and stations — rotating gracefully in space — are sleek, simple, and white, as if designed by Apple. Hal 9000 remains the definitive take on all that could go horribly wrong with AI technology, as well as the red, glowing eye of surveillance we fear lurks within our home cameras, virtual assistants and smartphones. There are science fiction films made within the last five years that already feel of-track, while "2001" continues to depict a plausible confrontation between man and machine through its mix of special effects, design and masterful direction.

Jurassic Park (1993)

Like "T2," Steven Spielberg's "Jurassic Park" stands out from the other films on this list because it wasn't created before CGI, but instead as an early opportunity to capitalize on the technology in its infancy. Spielberg was also smart enough to blend it with practical effects, keeping the CGI minimal.

As a result, the history of visual movie effects can probably be divided into two eras: before "Jurassic" and after it. Where the team excelled was in recognizing both the limits and the potential of the technology it had at its disposal, seamlessly blending it in with other tools in their kit to create a world that still tricks the eyes of the audience into believing it's real, all these years later.

Using a mixture of Stan Winston's practical effects and Lucasfilm's ILM, "Jurassic" employed animatronic puppets, a full-size animatronic T-Rex, stuntmen wearing Velociraptor suits and a deep study of animals like giraffes and elephants to understand how these animals would lumber, graze, and attack. Darkness was also harnessed in scenes like the famous Jeep attack (with the scene predominantly lit by one spotlight), allowing the ILM team to focus its energy (a single shot of the T-Rex took endless hours to create) on things like skin texture, teeth and light refraction.

"Jurassic Park" simply did everything right when it came to the visuals, on the bleeding edge of computer generated imagery, yet employing practical effects like close-ups of eyes and scales to sell the still jaw-dropping sequences of prehistoric creatures on the hunt. Plenty of movies that have come along since "Jurassic Park" have relied almost exclusively on CGI, but few of them have looked as good.