Why Mulholland Drive Is David Lynch's Best Movie

At least a few critics think "Mulholland Drive" is the best movie of the millennium, so calling director David Lynch's ninth feature-length film his personal best isn't much of a hot take. If we agree that the 2001 mind-bender — which you should watch before you read any further – outranks every other film produced since the year 2000, then suggesting it also rises above Lynch's other projects seems very reasonable.

Just like the owls, the takes are not what they seem.

If we gaze towards Rotten Tomatoes, we see that critical consensus grants "Mulholland Drive" an 84% freshness rating. That's lower than "Eraserhead" (1977) at 90%, "The Elephant Man" (1980) at 92%, "Blue Velvet" (1986) at 93%, and "The Straight Story" (1999) at 95%. All four of these films — indisputably essential watches in their own right — arrived before 2000, so they do not necessarily disrupt the notion that "Mulholland Drive" is the millennium's pinnacle of cinema. But if Lynch directed four superior films years earlier, that certainly pours cold water on the notion of "Mulholland Drive" as a supreme celluloid dream.

Our theory is Rotten Tomatoes isn't revealing the whole story. It's residing in a surreal fantasy world of symbolism and suspended logic, and when it snaps back into the real world (or a version of the real world), we will all see that "Mulholland Drive" is David Lynch's best movie after all. Let us explore this hypothesis further.

Its time-proof cultural relevance

The story has been interpreted in many different ways, and the ending of "Mulholland Drive" remains a matter of debate 20 years after it dominated the Cannes Film Festival.

But if we interpret the film literally, it looks like a story about a young woman who leaves her hometown and travels to Hollywood in pursuit of an acting career. Folks do that in the real world every day. In fact, folks did that every day for decades before Lynch had the idea of a "Twin Peaks" spinoff about Audrey Horne (Sherilyn Fenn) moving to Los Angeles. Folks will presumably continue this practice until some far-off day when L.A. is no longer the center of the movie industry.

Lynch pays homage to the equally timeless "Sunset Boulevard" (1950) throughout "Mulholland Drive." Both films document the seductive, duplicitous, and sometimes cannibalistic nature of Hollywood, which we can think of as a metaphor for countless other permutations of the American Dream. Lynch movies with higher Rotten Tomatoes scores also explore universal, ageless themes, but "Mulholland Drive" is the only one with an explicit, literal basis in everyday human behaviors and aspirations.

An unsettling, but compelling statement on identity and consensus reality

In the most grounded and widely accepted explanation of "Mulholland Drive," the initial two hours that focus on aspiring starlet Betty (Naomi Watts) and a mysterious amnesiac provisionally named "Rita" (Laura Harring) take place inside the slumbering mind of Diane Selwyn (Watts) — a struggling actor whose girlfriend, Camilla Rhodes (Harring), recently left her to pursue a relationship with up-and-coming director Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux).

The first part of "Mulholland Drive" is a "dream" world, the second part is the "real" world. But not everyone is convinced that's all there is to it, and since Lynch made sure Theroux doesn't know what's going on in "Mulholland Drive," obviously, no one else is ever finding out. But that's fine. What's "going on" in "Mulholland Drive" isn't the most important part of the movie.

Consider an alternate interpretation: the subjective, internal nature of identity is closer to the center of "Mulholland Drive" than any well-worn, if poignantly rendered, statement about how show business is full of phonies.

How do you see yourself? How do you think other people see you? How do you wish you could see yourself? How do you see people you're close to, and how would you prefer to see those people? What if the answers to all those questions were separate individuals played by the same actors in a film about Hollywood? If you're Diane, that movie would look like "Mulholland Drive."

Spot-on performances from Naomi Watts and Laura Harring

Ever since "Eraserhead" began drilling itself into the collective consciousness during the late '70s, a cult of personality has surrounded David Lynch. A powerful reputation for being weird turned him into one of the most famous directors of all time, even while the masses probably aren't particularly familiar with his work.

But if "Mulholland Drive" makes Lynch a genius, it does the same for Naomi Watts, Laura Harring, and Justin Theroux, all of whom deliver nuanced, gripping, affecting performances in a film totally unlike anything they had ever worked on before that point. Good job, movie stars.

As Diane and Betty, Watts does the heavy lifting in terms of the sheer number of minutes on screen and emotional range, going from childlike wonder to homicidal rage and despair. Harring's detachment — an in-story product of her character's amnesia — bolsters the rest of the film's sense of otherworldliness. Meanwhile, Theroux plays an entitled celebrity director as though he's met several individuals who fit that description throughout his showbiz career. Maybe he really does know people like that in real life.

It's an even balance of abstract and concrete elements...We think

Symbols and abstractions are part and parcel with David Lynch.

Precisely applied weirdness — especially Lynch's special variety of weirdness — can leave an audience mesmerized. On the other hand, too much weirdness can alienate viewers — turning potential fans into a confused, angry mob that demands a refund. A Lynch movie with no weirdness? Well, that's not a Lynch movie at all, unless it's "The Straight Story." But let's stay on topic.

Without making a value judgment on "Inland Empire" (2006) — which has already begun its critical reevaluation and redemption arc – maybe we can use the oft-misunderstood Laura Dern vehicle as an example of Lynch at his most potentially alienating. While plentiful twists and turns make "Inland Empire" equal parts enthralling and confounding, we can reasonably state that "Mulholland Drive" is a much more straightforward viewing experience. Don't worry, it's still plenty weird. Remember that practically omnipotent cowboy whose origins and purpose are never discussed? Or the dumpster monster? Yeah...

Basically, "Mulholland Drive" is Goldilocks's third bowl of porridge. It's not too normal. It's not too weird. It's juuuuust Lynchian enough.

Everyone wants to see Betty make it big in Hollywood, right?

The question of how much the audience must like or identify with a protagonist in order for a narrative to succeed is way, way too complicated for us to tackle here. Nevertheless, the fact that Betty is pretty easy to cheer for in the initial two hours of "Mulholland Drive" can't hurt the film, right?

Lynch's protagonists — Laura Palmer in "Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me" (1992), Dr. Frederick Treves (Anthony Hopkins) in "The Elephant Man," Sailor Ripley (Nicolas Cage) in "Wild at Heart" (1990), for a few examples — tend to be a morally ambiguous bunch. Even the innocent Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) in "Blue Velvet" (1986) sees the appeal of the dark side.

Betty, though, has a fundamentally well-adjusted, goodhearted nature that's rare for central characters in Lynch's film work. Despite her Hollywood ambitions, Betty passes on a major role in "The Sylvia North Story" when she realizes her audition could interfere with her efforts to help Rita regain her memory.

If we factor in the lengths she'll go to help out a friend, plus her obvious interest in solving mysteries, Betty appears to have a lot in common with Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) — the spiritually inclined hero-detective on "Twin Peaks." To indulge in some speculation, perhaps it is not a coincidence that Lynch originally envisioned Betty as the main character of a "Mulholland Drive" television series.

The unforgettable horror of Winkie's diner

While the three leads of "Mulholland Drive" deserve the utmost credit, we don't owe them an iota of praise for the film's most memorable scene because not one of them is in it.

Dan (Patrick Fischler) and Herb (Michael Cooke) — about whom we're provided essentially no information — meet at Winkie's Diner on Sunset Boulevard to discuss Dan's recurring bad dream. Dan reports dreaming, on two occasions, of a man who lives behind Winkie's and inspires all-consuming, petrifying fear, even absent any tangible threat. Dan dreams of inexplicable abject terror, and only knows that the man is "the one who's doing it."

After this conversation, the pair check behind the diner to prove Dan's scary man isn't real, like showing a child the inside of a closet to show them there's no monster within. However, sure enough, they bump into the man — officially known as "Bum" (Bonnie Aarons) — whose sinister smirk abruptly glides into the frame. Dan collapses, presumably dead from shock.

The interior of a franchise diner — a universally familiar setting (for Americans, at least) — creates a false sense of comfort offset only slightly by Dan's awkward mannerisms and clearly rattled state of mind. Tension builds and hits a ruthless apex just as the Bum casually steps out from behind their hiding place. The phrase "nightmare fuel" doesn't do it justice.

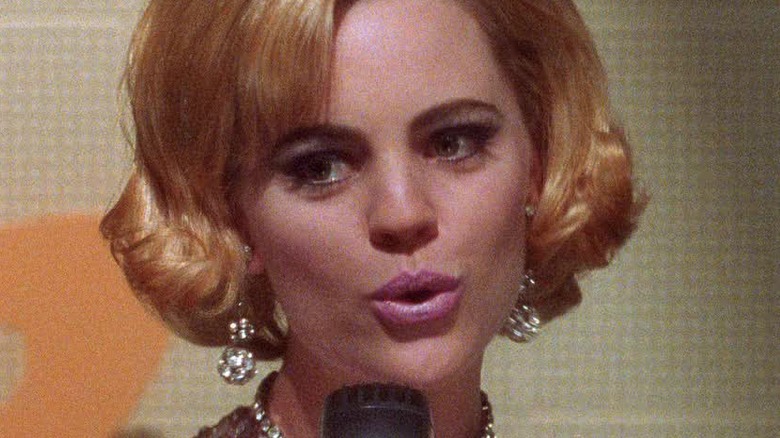

Rebekah Del Rio at Club Silencio

At the threshold between the first section of "Mulholland Drive" and its grittier conclusion is singer Rebekah Del Rio, who unleashes a heart-shattering a cappella rendition of Roy Orbison's "Crying" at the incomprehensible Club Silencio. The interlude provides an emotional crescendo for the whole film, as well as a moment of simple pathos in the midst of a tangled web of violence, sex, and mystery.

In some respects, it's the inverse of the sequence from Winkie's. Both are digressions from the main plot; while the Bum behind Winkie's offers shock, horror, and possible death, Club Silencio offers a glimpse at the sublime.

The host of Club Silencio isn't subtle when he tells us what we see on stage is not what it sounds like; we shouldn't allow ourselves to get comfortable here. Despite the warning, Del Rio's mid-song collapse — and the revelation that this is only a recording — is an omen of doom.

Angelo Badalamenti does his most penetrating work since "Twin Peaks"

Calling the "Mulholland Drive" soundtrack Angelo Badalamenti's "best" since "Twin Peaks" might not be accurate simply because the composer has done so much excellent work. His oeuvre includes many projects that don't involve David Lynch — the kinky romcom "Secretary" (2002) and "A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors" (1987), for instance — plus soundtracks we haven't heard that play in films we haven't seen. But from a purely subjective, emotional standpoint, Badalamenti's score for "Mulholland Drive" feels like his most enduring sequence of cinematic music outside of the multiple unforgettable themes of "Twin Peaks."

The lively big band number echoing from memories of a jitterbug contest, incidental jazz refrains, thoroughly haunting main themes, the brighter but subtly foreboding ambiance from Betty's arrival in Los Angeles — Badalamenti freakin' kills it on "Mulholland Drive."

The plot is much easier to follow than "Eraserhead"

David Lynch put himself on the map with "Eraserhead." Out of all his feature-length projects, it's the least tethered to any sense of traditional linear storytelling, and the most aggressively disturbing. The extent to which the surrealist, semi-horror movie concerns itself with the exterior world at all is questionable. Inspired by Lynch's time as a student in Philadelphia, it's a deep dive into the subconscious. We think "Eraserhead" is a metaphor for the onset of fatherhood and related anxieties, but do not quote us on that.

"Mulholland Drive" also has plenty of nonlinear and symbolic elements, but they're all anchored to Betty's mission to solve the mystery of Rita's broken memory and the origin of the bag full of cash. In a vacuum, that's all very simple to understand. In "Eraserhead," Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) displays plenty of emotional turmoil, but with so many images and sounds with no obvious connection to each other blasting into our eyeballs, it's harder to relate to Henry's half-existential crisis.

Also, is it insane to suggest a movie Lynch made after decades of experience is an overall superior product compared to his first effort? It certainly isn't.

"The Elephant Man" isn't really "Lynchian"

Any film directed by David Lynch counts as a David Lynch movie, of course. However, let's say someone is watching a film, and that film depicts a strange occurrence. If the viewer says, "This is just like a David Lynch movie," do they mean it's like "The Elephant Man?"

Probably not.

The Oscar-nominated 1980 historical drama tells the tragic, semi-true tale of John Merrick (John Hurt) — a severely deformed man who lives much of his life in de facto captivity as a sideshow freak, and spends a brief, happy period amongst London's high society.

We can describe "The Elephant Man" as strange in that its central character does not look conventional, but its story unfolds in a relatively traditional manner. If you find yourself having difficulty following the plot of "The Elephant Man," it's not because of Lynchian shenanigans.

David Lynch movies aren't always confusing. But you'd expect that even one of his simpler, less enigmatic films would contain a handful of his signature motifs — extended musical interludes, tone-heightening plot detours, blue or red curtains, Laura Dern and/or Kyle MacLachlan. "The Elephant Man" contains none of these.

Of course, "The Elephant Man" is a David Lynch movie...but is it enough of a David Lynch movie? "Mulholland Drive" is far more emblematic of Lynch's style.

"Mulholland Drive" is much funnier than "Blue Velvet"

Lynch's return to acclaim and respectability following the debacle that was "Dune" (1984), "Blue Velvet" both celebrates the comfort and simplicity of middle-class American life, and faces down — and maybe even indulges in — the violence and madness lurking under its surface.

We could argue "Mulholland Drive" is to Hollywood as "Blue Velvet" is to suburbia. A crucial part of Lynch's oeuvre and a blistering examination of the human condition as he's experienced it, "Blue Velvet" goes fairly light on abstraction, and isn't funny (except maybe in moments of extreme absurdity or high camp).

While "Mulholland Drive" hardly qualifies as a comedy, it includes Mark Pellegrino as the world's least effective hitman, and Coco the landlady (played by Golden Age of Hollywood alumna Ann Miller) screaming about dog poop in the courtyard of her building. Jeffrey Beaumont's (Kyle MacLachlan) chicken walk is the closest thing to an effective joke in "Blue Velvet," and it does little to leaven the movie's considerable amount of graphic sexual violence.

"Blue Velvet" draws a stark line between its light and dark moments, but "Mulholland Drive" embraces the shady morality of a world characterized by both unmatched highs of glamor and wealth and lows of complete despair. The same actor plays the virtuous hero and the unhinged, homicidal villain, and why not? Depending on when it's said and who hears it, a line like "this is the girl" can mean all kinds of things.