The Ending Of Halloween H20 Explained

When the original "Halloween" hit theaters in the fall of 1978, it managed to do two very important things at once. Firstly, it introduced the world to a young actor named Jamie Lee Curtis, arguably Hollywood's preeminent scream queen and most compelling Final Girl. Secondly, in the adept hands of director John Carpenter, it succeeded in bringing a more nuanced and relevant thematic resonance to a still-fledgling sub-genre — one that hadn't been explored since the film's ancestral inspiration, Alfred Hitchcock's "Pyscho," was released in 1960.

In 1998, director Steve Miner took up the mantle with "Halloween H20: 20 Years Later," a film that disregarded most of the franchise's less successful (read: pretty bad) chapters and acted as a direct follow-up to Rick Rosenthal's 1981 sequel, "Halloween II."

On the other side of David Gordon Green's wildly successful rejuvenation of the franchise, it's clear that although the late-1990s revamp is, in many ways, very much "of its time," it nonetheless managed to hold on to the narrative's thematic through line, or, what Curtis once referred to as "the essence of what makes something like Halloween special" (via Vogue). Nowhere is this more apparent than in the film's exploration of trauma, and its ending's hyper-focus on what the dynamic between Curtis' vigilant Laurie Strode and (various actors') murderous Michael Myers has to say about what they represent.

Halloween: H20 made an admirable attempt at investigating the nature of trauma

Two decades after Laurie Strode was first terrorized by her own personal boogeyman, "Halloween: H20" attempted to explore how her initial run-in with Michael Myers might permanently impact her emotional growth and mental wellbeing. After faking her own death, adopting a new persona, and continuing to raise her teenage son John (Josh Hartnett, because 1998), Laurie Strode is still struggling with a suffocating (and, as it turns out, justified) paranoia of her murderous brother that exhausts and infuriates her restless son. Strode has nightmares, takes medications, chugs vodka like its La Croix, and refuses to let her son so much as go on a highly-supervised field trip. Nobody but Laurie Strode understands the depth and real-time relevance of what she experienced, not her son, not even her skilled and sympathetic counselor boyfriend. Both men tell her "it's been twenty years," as in, "shouldn't she be over this by now?"

That number is important. It acts as a reminder that when it comes to traumatic events, time works differently. The "Post" in Post Traumatic Stress Disorder is often an unintentionally cruel misnomer. For the trauma survivor, the mind and body can remain frozen in the space and time in which the trauma took place for years, if not in perpetuity. Trauma is not a wound time alone can heal, the film tells us, because reminders like, "it's been (x) amount of years" only serve to further invalidate an emotional and physical response for which the victim is not responsible. the notion that time alone should "cure" this affliction is its own brand of victim-blaming. As in the original, "Halloween: H20" suggests that you really "can't kill the boogeyman," neither in his physical nor in his existential/emotional form.

Halloween: H20 never lost sight of what Laurie Strode's struggle represented

Although in her recent interview with Vogue, Curtis confessed she wasn't entirely convinced of the film's ultimate ability to do this — "I wanted to explore Laurie's trauma...I would've been able to see my vision through if I'd been a producer, but I was a mom," she told the outlet — there's plenty of evidence in the film to suggest that's exactly what it intended (at least) to do. But in addition to attempting to validate the trauma survivor, "Halloween: H20" places a more explicit focus on the misogyny inherent in Michael Myers' psychopathy. Far from being the flighty, hyper-sexualized teen girls that ran rampant in the more unwatchable eighties slasher flicks — an archetype Billie Lourd's Montana Duke explored and exposed in "American Horror Story: 1984" — the women of "H20" are self-assured, self-possessed young women. Yes, they have boyfriends, and yes, they're sexually active with those boyfriends, but there's no tropey, moralistic subtext imbedded in said sex. The two young women, Sarah (Jodi Lyn O'Keefe) and Molly (Michelle Williams, best known at the time for "Dawson's Creek"), are in control of their own bodies and their sexuality, neither of which are exploited in the film for cheap, sex-and-violence thrills.

Sarah, in particular, demonstrates an acute awareness of the power dynamics at play between men and women when it comes to sex. When asked by their guidance counselor how they intend to spend Halloween, Sarah says "well, we thought we'd hit the town, pick up some guys, y'know, drop some Roofies in their drinks...have a whole date-rape evening." It's a small moment, but an important one, and although the hyper-aware, Tori Amos-esque Sarah is ultimately killed by Myers, (it is, after all, a slasher flick) the film never posits her as the victim of her own sexuality. In having her die at Myers' hand, "H20" brands the killer as a manifestation and personification of misogyny, rather than a moralistic entity doling out "just rewards" for anyone who dares to have sex.

Halloween: H20's ending established Laurie Strode as a badass

In both 2018's "Halloween" and 2021's "Halloween Kills," fans were finally given a fully-fledged version of Laurie Strode that explored the impact of her trauma without making said trauma the defining characteristic of her being. Although "Halloween: H20" isn't necessarily consistent in its endeavor to do the same, it did portray Laurie Strode with the same depth and intellect with which Debra Hill had first envisioned her (via New York Times). Moreover, its final scenes act as a powerful foreshadowing of what was to come by establishing the heroine as an inverted representation of (and foil to) her brother.

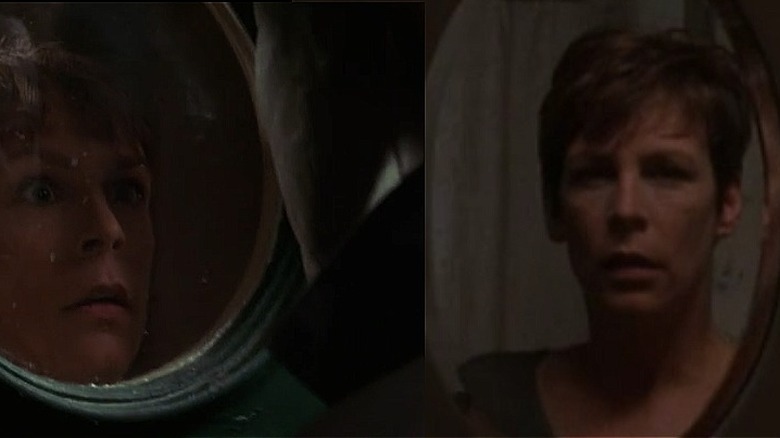

When Laurie finally comes face-to-face with Michael Myers (Chris Durand), the film frames their interaction as a literal reflection, alluding to an earlier scene in the film wherein Laurie is looking in the mirror and attempting to ease her nerves and gather her strength. As she leaves the bathroom in the mirror scene, she says "f— it." By framing her first up-close encounter with Myers in the same manner — despite the abject terror in her face in the latter — the film suggests the protagonist will ultimately succeed in breaking free of the hold her brother has over her. Of course, the only way to do that is for Stroud to not merely survive her monster's attack, but to ensure he does not, by necessarily becoming a kind of monster herself. When Laurie, John, and Molly finally break free of Myer's pursuit, Laurie doesn't escape alongside the teens, but tells her son and his girlfriend to drive away before locking herself in the campus with Michael and high-kicking open a glass case housing an axe.

The ending of Halloween: H20 kicked-off a new theme

After seemingly — but of course not really, as she well knows — fatally wounding her brother, Laurie intercepts the coroners' removal and transport of the body by holding them at gunpoint in order to hijack their van and the body bag containing Michael. Laurie's focus is on one thing and one thing only — ensuring that the Implacable Man of her torment is undeniably, un-resurrectably, once-and-for-all, all the way very much dead. After ejecting her indestructible brother through the van's front windshield and then driving herself, the van, and Michael off a fairly steep slope (nearly killing herself in the process), Laurie is again framed both literally and thematically as an inverted mirror image of Michael.

(Although the film's 2002 follow-up, "Halloween: Resurrection," would reveal that the body with which she was interacting was not actually Michael, but a paramedic he'd managed to disguise, neither Laurie nor the film/audience itself are aware of this. Subsequently, the man she pins between the van and a tree, and then beheads, must be treated as Michael in the film's analysis).

In yet another overt demonstration of Laurie's unbreakable, if oppositional, connection to her brother, the final scene shows protagonist and antagonist reaching out toward one another, and almost (but not quite) grasping one another's hand. In its repeated framing of the siblings as mirror images of each other — distinct, yes, opposite, yes, but nonetheless reflective — "H20" explores the complex dynamic between the two that David Gordon Green's reboot would further explore. At times, Laurie represents everything Michael is not, and vice versa. At other times, she has to embrace the violence, hate, and unshakeable single-mindedness of his psychopathy in order to destroy him, thereby "freeing" herself and others, but at no small cost.