What CSI: Miami Gets Wrong About The Crime Lab

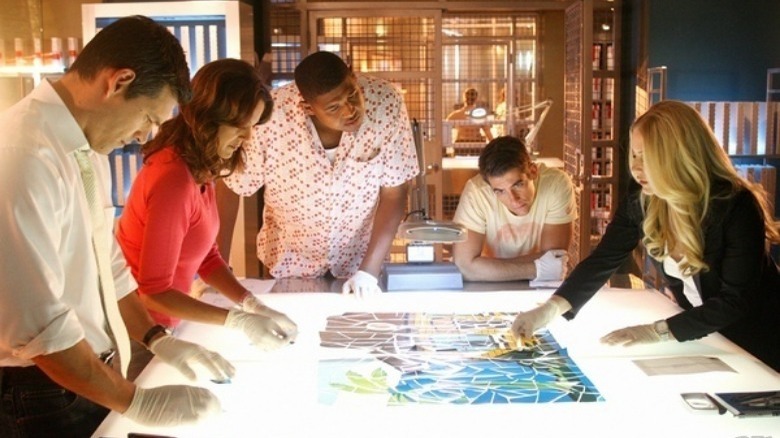

"CSI: Miami" wrapped in 2012, but it lives on forever in syndication. As the original Las Vegas-set "CSI" begins its second life, fans' minds turn nostalgically to other franchise arms. "CSI: Miami" ran for 10 seasons, lasting almost as long as its parent series. For all 10 of those seasons, the show starred David Caruso as the sunglasses-wielding Horatio Caine. He was always supported by Calleigh Duquesne (Emily Proctor) and had Eric "Delko" Delektorsky (Adam Rodriguez) for the majority of the show's run. Other specialists would come and go, but these three were stalwarts in the field and the lab, steering investigations.

According to criminologist Jennifer Shen, that is the biggest issue with every "CSI" franchise. The people gathering evidence are not the people leading investigations. "CSI's tendency to use the criminalists as sounding boards for investigative theories makes it appear the criminalist is part of the investigative team," she told Looper. Criminalists, either in the lab or in the field, can't get involved in the investigation because it would ruin their impartiality when examining the evidence. Science works best when the scientist doesn't have a motivation for a specific outcome. "If that analyst knows that the entire case rests upon this one piece of evidence, and they know the details of the crime," Shen says, "might they be tempted to be more liberal in their interpretation?"

But a show where scientists impartially analyze evidence without any context doesn't sound like good television, does it? We can forgive the factual error upon which the entire "CSI" franchise rests, but it's hardly the only thing "CSI: Miami" gets wrong about the crime lab.

Crime scene personnel don't analyze their own evidence

Even if we ignore that the crime scene investigators on "CSI: Miami" are a blend of detective and criminalist, Caine et al. still do too many jobs. In real life, the field techs and the lab techs aren't the same people, either. One group gathers evidence, another processes it. According to Morgan Turano of The Take, this is for many reasons. First, Miami has a lot of crime. Two groups can intake and process twice the evidence. Second, there is that implicit bias rearing its head again. The more the job is broken up into smaller parts, the fewer pieces of the narrative any technician has and the freer they are to interpret the data without emotion.

Finally, evidence collection takes a lot of finesse. "Having a lab technician who is used to working with blood samples try to make a cast of tire tracks in mud could be disastrous," Turano says, "and having extraneous people at a crime scene can damage or contaminate evidence." The Edgar Wright film "Hot Fuzz" shows what a real CSU looks like — people in cleansuits and booties. They are trying to remove themselves from the narrative.

In real life, crime scene contamination is a huge problem. Contaminated crime scenes may have stalled the JonBenet Ramsay case and in identifying the Phantom of Heilbronn.

Everybody has a specialty

But back in the crime lab, the specialization goes down even further. In fact, it's specialization all the way down. On "CSI: Miami," the members of the crime lab have ostensible areas of expertise. Caine is the explosives guy, Callie does ballistics, and Delko (improbably) is in charge of underwater evidence, drug identification, fingerprints, and tire tracks. Until his death, Speed was the blood spatter guy. But the show tends to have every character do everything. Sure, Callie will be the one to compare bullet casings, but that usually doesn't stop her from weighing in on things like DNA evidence. In the real world, each crime lab tech does just one thing.

Let's drill down on Delko's specialties. Underwater evidence collection would require hours of diving certification and probably some courses in something along the lines of underwater archaeology to understand how tides could disturb evidence. Drug identification would involve a chemistry degree. People spend years studying tire tracks and fingerprints. A good tire track specialist would probably have to know everything about cars and at least a smidge of physics and geology. Adam Rodgriguez was 27 when "CSI: Miami" premiered. His character couldn't possibly have all the training required to do every part of his job unless "CSI" secretly takes place in the "Harry Potter" universe, and Delko has a time-turner. Speaking of time management...

It takes so much more time

Even with all the specialization of an actual crime lab, gathering and interpreting evidence takes so much longer than it does on "CSI: Miami." According to a report compiled for the Connecticut Governing Body, DNA results on a homicide case could take up to 90 days back when "CSI: Miami" was on the air. If a detective asked the crime lab to put the case on "rush," they could get that time down to 76 days.

The individual tests themselves don't take 90 days. Instead, we're back to the issue of crime labs being extremely busy. The Boston Globe reported on chemist Annie Dooken, who was accused of analyzing samples with explicit bias — making the evidence fit the theory rather than examining results impartially. She worked 34,000 cases in eight years, averaging 4250 cases a year. "CSI: Miami" solves maybe 2 cases a week, meaning a real big city crime lab would be processing over 40 times as many cases in a year than we see on TV.

Detectives will sometimes beg or even bribe a crime lab tech to jump the line on more realistic shows. On "Bosch," Harry Bosch (Titus Welliver) would regularly threaten or flatter tech Lester Poole (David Lengel) with booze to get his cases processed in a day or two.

While "CSI: Miami" might get a lot of things wrong about what goes down in the crime lab, fans have to remember a story cannot be fleshed out in an hour if it were sticking to real-world rules. We forgive in the name of entertainment.