The Ending Of Home Sweet Home Alone Explained

In 1729, an anonymous author later revealed to be Jonathan Swift published an essay suggesting the solution to Ireland's widespread poverty and starvation was clear: the poor should simply sell their children as food. "A young healthy child well nursed, is, at a year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food," it reads, "whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled" (via Project Gutenberg). Whatever its reception at the time, the work — its full title is "A Modest Proposal For preventing the Children of Poor People From being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and For making them Beneficial to the Publick" — remains one of the literary world's most preeminent examples of political satire.

Nearly three centuries later, co-writers Mikey Day and Streeter Seidell created what will no doubt be regarded in the decades to come as an equally preeminent example of holiday movie satire, "Home Sweet Home Alone." That's because the film, although marketed as an "actual" holiday movie/sequel, boldly defies its audience to take it seriously, either as a heartfelt Christmas comedy or as a narrative with any semblance of believability or meaning outside of the mission explicitly laid out in the movie's tagline. "Holiday classics were meant to be broken," it told us, before intentionally doing just that.

The creators of Home Sweet Home Alone had us fooled

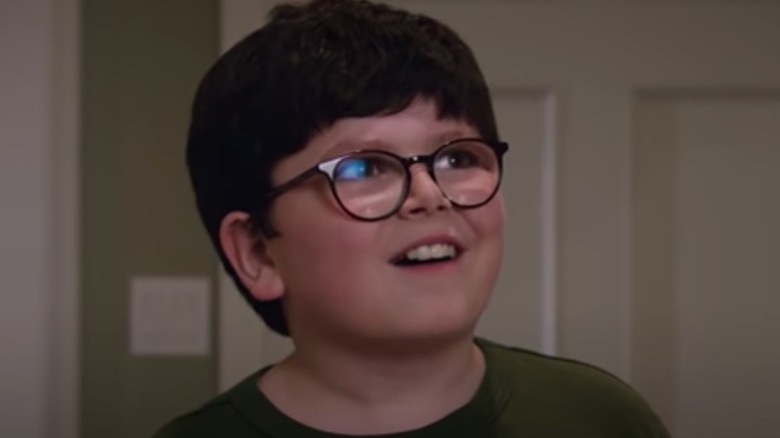

The premise of Disney+'s "Home Sweet Home Alone" is just similar enough to the original to make its point heard. In director Dan Mazer's (pictured above) sixth installment of the holiday franchise, a scattered and stressed-out family of extremely wealthy people accidentally leave a kid behind on their way out of the country (only this time, their destination is Tokyo). Unlike Macaulay Culkin's adorably guileless Kevin McCallister, Max Mercer (Archie Yates) is 10, not 8, and a precocious British child who boasts a level of snark well beyond his years. That the young protagonist (though not the actor who portrays him) is pretty difficult to like is intentional and a calling-out of the long-held belief that holiday movies must give audiences someone to root for and learn alongside.

The burglars of this sequel are different, too, and come in the form of a struggling upper-middle-class couple with two children. Pam and Jeff Fritzovski (Ellie Kemper and Rob Delaney) are forced to sell their home and move into what we presume is a slightly smaller middle-class home after Jeff loses his job in the wake of the "data migration boom." But they find hope in a surprise source of revenue when Jeff learns that an ugly antique doll of his mother's recently sold for over $200,000 on eBay. Mistakenly believing that Max stole the doll while using their bathroom at a recent open house, the Fritzovskis resolve to break into the multi-million dollar Mercer home and steal said doll back.

Of course, Max — who, at 10, thinks they're after him because they want to sell him to old ladies — has other plans. As an audience, we're bombarded repeatedly with leaps in logic and irrational decision-making that's so, so far outside the realm of reason or sense, it's clear the creators weren't just testing our willful suspension of disbelief. (Or our ability to pick up on references to the original.) As it turns out, they had something totally different in mind.

Home Sweet Home Alone has something to say about sentiment

"Home Sweet Home Alone" leans into gestures like a tech guy who's apparently never heard of VR technology, a twenty-first-century 10-year-old who doesn't know how to use anything other than a digital home assistant to call his parents, and two grown adults with kids (and guests) of their own who don't even bother to look around their own house before deciding the doll is at the Mercers. By doing so, the film is at once calling out our typical credulity and our old-fashioned affection for the obsolete sentimentality that runs rampant in traditional holiday movies and specials.

Nowhere is the movie's disdain for (and mockery of) sincerity, meaning, or that all-elusive element known as "heart" more apparent than in its ending. Naturally, after putting the Fritzovski couple through a "maze of death" similar to that dreamt-up by the original film's protagonist, the trio stops doing battle just long enough for the story's "Three's Company"-esque miscommunications to come to light. The couple takes Max home to wait for his mother, they learn the doll was with their nephew all along, and all's well that ends well. And just like in the traditional holiday movies it attempts to expose, "Home Sweet Home Alone" ends with somebody learning something.

A genuine miracle occurs at the end of Home Sweet Home Alone

Now that she knows she'll be able to keep her very nice, upper-middle class home (because the eBay thing), Pam Fritzovski looks up at her husband and says, "I guess home is ... just another word for family, right?" See, in a more genuine holiday movie, the protagonist would learn that only after being forced to let go of their prized material possessions. Joke's on you, says the ending of "Home Sweet Home Alone," because that idea is STUPID, and you know it.

"I'm so glad they're not poor anymore," Pam's rich and insufferable sister-in-law says to her rich and insufferable husband. As it turns out, they're not, and that's where the Disney+ reboot of John Hughes and Chris Columbus' 1990 smash-hit reaches peak irony. Because the only holiday "miracle" you'll find amidst the "awkwwaaaard, LOL"-style humor, aggressive genre commentary, and slow-motion slapstick mayhem of "Home Sweet Home Alone" is this: A doll that sells for just over $200k on eBay is somehow able to cover the family's upside-down mortgage, a trip to Europe, and thousands upon thousands of dollars worth of property damage.

Whether the film's creators simply hated the original "Home Alone" or just take issue with contemporary society's hypocritical love for a genre that pushes "The Heartfelt Agenda while tearing one another apart on Twitter, we may never know. What is clear is that the ending of "Home Sweet Home Alone" acts as a brilliant and hilarious punctuation mark to the film's scathing commentary on the toxicity of holiday sentiment and hope.