King Richard Review: Father's Day

The burning question going into "King Richard," the latest Will Smith vehicle, is not whether he's still got the chops for more serious roles, or even whether audiences will find a way to care about tennis, but rather: given how undeniably phenomenal Venus and Serena Williams are as sports icons, how is their dad the one getting the biopic? Sure, the film itself does make the sisters (played here by Saniyya Sidney and Demi Singleton, respectively) key figures in the narrative. As a movie, it centers the entire Williams family, including unsung matriarch Oracene Price (Aunjanue Ellis), but it is still called "King Richard" after Smith's Richard Williams, the charming, fallible father at the heart of the story.

Before there was LaVar Ball, putting himself center stage ahead of his ball-playing sons like Diddy in an oversized music video cameo, there was Richard Williams, a man with the "plan," an unconventional and detailed blueprint for training his Black daughters from Compton in an extremely white sport. Now, his daughters are household names, generational talents, and indisputable figures in sport history, but during the time this film covers, Richard, the ridiculous huckster literally no one believed in, was the star of the show.

But the problem with the film's focus being on Richard is more of a feature than a bug, a built-in conflict that must, in the film as in the true story it's based on, be reckoned with for his "plan" to truly come to fruition. Also, it helps that Smith, as Richard, delivers arguably the best performance of his career, even if we, the audience, spend much of the runtime trying to shoo him off the screen to make space for the real stars.

Stick to the plan

"King Richard" begins in the late '80s in Compton, California, where Richard stretches himself thin working a security job and training his girls day and night, rain or shine, much to the chagrin of the neighbors who see him as an abusive tyrant. Through a hilarious and discouraging montage, we see the elaborate plan, complete with pamphlets and home video pitches, Richard has devised to help his daughters acquire "real" training from more famous or affluent tennis coaches, but he is thwarted at every turn. Undeterred, he and the family forge ahead, despite their socioeconomic and racial standing being a genuine barrier to moving further within this particular sport.

For much of the film's first third, it's difficult to truly engage with the material beyond being enamored with Smith's equally uproarious and heartbreaking performance (and the ensemble dynamic within the larger Williams family unit). Every time Richard gets sniped at by some country club snob, the sting of their obvious shortsightedness immediately gives way to the natural comic relief of knowing better how this story ultimately plays out. There's only so much dramatic irony one can take of random, stuffy white folks in ugly clothes saying how unlikely Richard's plan is when we know for an empirical fact this story has the happiest of endings.

So Zach Baylin's script, and the way director Reinaldo Marcus Green helms the picture, instead piles on the adversity to melodramatic heights of misfortune. The story inflicts a lot of punishment on Richard, specifically, as he's bullied by strangers, literally assaulted by local gangbangers, and otherwise disrespected at every turn. It may seem like overkill at first, but it's necessary to make this leg of the film work.

At multiple intervals in the film's first half, the quirks and cadence of Smith's performance, an exaggerated impression of the real Richard and his Louisiana drawl, call to mind Eddie Murphy's work in "Dolemite Is My Name." Of course, anytime one finds themselves thinking about Eddie Murphy it's not a long walk to wonder why he wasn't cast instead. But Smith has an inherent quality to his screen presence that is hard to deny. Like the best pro wrestling babyfaces, Smith has an uncanny ability to earn sympathy from the viewer — something Murphy, at his core, would just be too cool to really do in this part. Smith is able to make Richard the kind of lovable loser who can fall down repeatedly and, through perseverance, earn our respect and admiration. (Just look at all the secondhand sympathy he gets in the media every time his wife Jada shares new information about their unconventional marriage.)

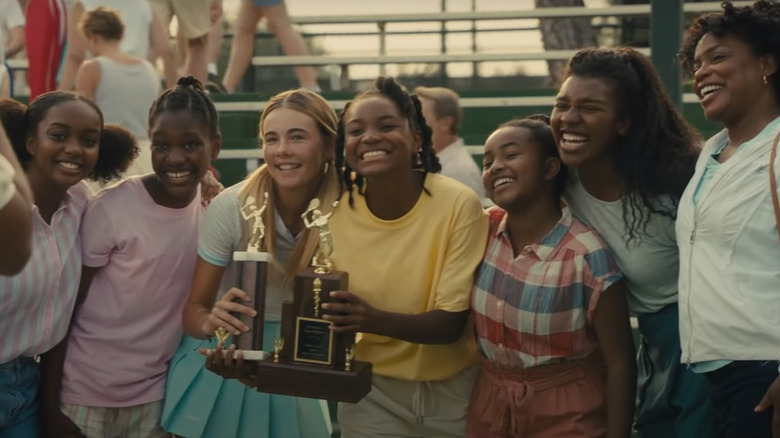

It's enough to carry the film to the real meat and potatoes, when Venus and Serena start getting trained by Paul Cohen (Tony Goldwyn), and Venus starts crushing it in junior tournaments, where the sort of controversies that plagued both women's professional careers play out in miniature. The film riles the audience up at the inherent racism of the other players, and more importantly their parents, while simultaneously releasing that tension every time Venus wins a game. It's a truly fascinating balancing act of frothing folks up in righteous and understandable anger before the curative salve of seeing this indomitable little girl find herself on the court.

That's where "King Richard" finds itself — and where it nearly loses its way.

Papa don't preach

Once Venus — and later, her younger sister Serena — start killing it at junior tournaments, it feels like the film should shift to their perspective. The struggle of getting them to the point that they're being trained by big shots and fielding endorsement deals means, on some level, that Richard's struggles have paid off. But navigating this world is still a thorny battlefield. There's a time jump in the second act, after the Williams family detaches from coach Cohen and moves to Florida with Rick Macci (a delightful Jon Bernthal), the man who discovered previous teen girl tennis phenom Jennifer Capriati. Richard pulls Venus from playing in juniors so she can train and go to school full time, worried she'll experience the same kind of horrid burnout Capriati did.

But Venus wants to go pro. She wants to play matches. She wants some manner of control over her life, something Richard refuses to cede. It's in this section of the film that the question of making Richard the lead feels like a baked-in element of the film's story, but it's also where it feels like framing all of it from his perspective feels like a mistake. The movie sets up a number of interesting conflicts about the minefield that is sports endorsement deals, about Serena's jealousy of Venus being older and further along, and most importantly, of Oracene being so marginalized within the branding myth of Richard and his "plan."

When it all comes to a head and less than desirable elements about Richard's past and practices come to light, the viewer may find themselves wishing they were watching a movie that wrestled with these ideas from the jump. It isn't that the movie needed to be a warts-and-all look at pushy athletic parents or a tragic treatise on the travails of a father who wants more for his children than he had, but it spends so much energy on Richard's arc that it unintentionally makes everybody feel ancillary. Perhaps in a television miniseries or something there would be more space to juggle the rest of the family, but for this form factor, it's the Richard Williams Show until it isn't — and then it becomes an argument about it being the Richard Williams Show.

Trying to engage with the gift and curse of Richard's showmanship, and how much of this is truly for "his girls" and how much is for himself, gets in the way of the film's most touching and important element. The real thesis "King Richard" seems to settle on late in the game is that the Williams sisters' success isn't rooted in getting the right training or working with the right people, or even all the playing in the rain their father forced them to do. It posits that the love and support their parents gave them, the undying devotion they could always count upon, helped build a foundation of self-confidence necessary for young Black athletes to navigate a world that works against them at every turn.

With the gift of hindsight, we can look at the myriad controversies and media blunders that have befallen both Venus and Serena over the years and recognize, rightly so, that the formative work done by their folks at a young age equipped them to handle, well, literally anything thrown in their path.

That's the brightest part of "King Richard": the way it celebrates and exalts the transformative power of a father's love.