The Power Of The Dog Review: Best In Show

When tackling the subject of toxic masculinity, some directors aim to make brooding character pieces; subtle dramas that slowly unfurl the poisonous worldview of their lead. Jane Campion, however, has opted to explore the subject by depicting a central character who likes bathing in mud and delivering monologues about how he loves how much he stinks, his toxicity becoming literal and unavoidable. Not since Andrew Garfield's misogynistic drifter was sprayed by a skunk in recent cult classic "Under the Silver Lake" has a film delighted in making something that was already toxic inescapably rancid, the only breath of fresh air viewers will have being the sigh of relief that Netflix didn't send out novelty scratch and sniff cards to anybody streaming it.

"The Power of the Dog" is Campion's first feature film in 11 years, and it serves as the perfect entry point for a contemporary audience largely unfamiliar with her prior work. The director is often unfairly categorized as something of an arthouse acquired taste who specializes in slow-moving, period-set literary adaptations with a dreary worldview. Her latest film ticks off two of those boxes (this is a period-set literary adaptation), but transforms a haunting study of masculinity in crisis into something far more uproariously melodramatic — this is a film where a toxic man refuses to bathe to make himself repulsive to everybody around him, after all — but no less moving because of it.

Bark and bite

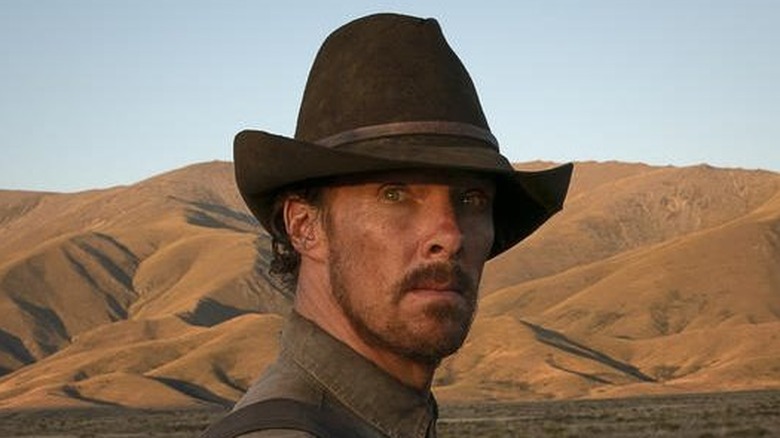

This repugnant central figure is Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch), a man who revels in the cruelty he affords others. He may jointly own his Montana ranch with his more personable brother George (Jesse Plemons), but it's his sibling for whom he reserves the most spite, routinely calling him the same nicknames he has since childhood and undermining him wherever possible. Cumberbatch, in one of his strongest performances to date, leans in to the psychodramatic theatricality of Phil's controlling behavior, on a whim unleashing playground insults ("fatso" seems to be his personal favorite) or changing the conversation to the more embarrassing interludes of his brother's past to exert dominance over him. But when we meet Phil, this performative need to engineer each situation to his favor has become easier for others in his orbit to see through. Plemons has the most understated performance of the four leads, perfectly articulating a quiet exasperation, refusing to acknowledge the lines his brother frequently crosses.

From his introduction onwards, Phil Burbank is already a deliberately outsized caricature of masculine ideals, displaying a desperate need to show that he is worthy of stepping into his mentor's shoes, in addition to being his brother's antithesis. In one early scene, he lashes out at his brother for refusing to drink a shot with him — his subsequent retaliation only exposing him as the small man in the situation. Campion's screenplay, adapted from Thomas Savage's 1967 novel, doesn't make time for subtlety when it comes to the inner complexities of his character either, becoming abundantly clear early on that his hyper-masculine behavior is in part a repression of deeper homosexual desires. I know what you're thinking — a toxically masculine bully in a movie is secretly gay? How groundbreaking. Thankfully, the director manages to avoid cliche in the way she addresses this, with the queer themes largely unspoken, reduced to nothing more than passing glances, the characters only articulating their inner desires through the way they talk around them. A more conventional version of this film would have Phil forced to confront this head on, but Campion is far more interested in exploring how that closeted trauma becomes generational.

She does this via the introduction of waitress Rose (Kirsten Dunst) and her teenage son Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee), both of whom become objects for Phil's psychological brutality. Rose is a piano player who has moved to rural Montana after a big city life playing the musical accompaniment to silent movies. George is immediately smitten with her, much to his brother's disdain, which is partially due to his repression getting in the way of romantic contentment, but more so for the fact that Rose has raised a son he considers a laughingstock. If Phil has learned how to hide who he is through a facade of machismo, then Peter stands no chance. His every body movement is feminine (to any audience members who don't pick up on that straight away, Campion includes a lingering shot of Peter playing with a hula hoop just so you're certain), his voice strained by a lisp. In classic bully fashion, Phil belittles him upon first sight, only to increasingly find himself forging a role reversal of his own relationship with his long-gone mentor, if only to give him a more respectable identity he can show off to the world.

A Post-Western

But that relationship comes a distant second within the narrative to his controlling relationship with Rose. There are easy surface level comparisons to be made to Campion's best known film, her 1993 Oscar nominee "The Piano," in which a psychologically abused woman sold off to marriage finds herself used for sexual favors in order to regain control of her beloved instrument. "The Power of the Dog" acts as its inverse, as Rose is tormented by Phil every time she sits down to play, in the most harrowing use of banjo since "Deliverance." This mind game, of simply drowning out her rehearsal, leads to her eventual inability to play at all, the removal of music from her life triggering a further downward spiral.

The score by Radiohead's Jonny Greenwood (one of his three impactful scores this awards season, having also contributed the haunting music for "Spencer" and the far more melancholic "Licorice Pizza") emphasizes the menace to this constant musicality, refraining from using banjos, but utilizing several instruments associated with the country genre. Never is this more affecting than in the score's most recurrent refrain, "25 Years," the constant plucking of strings almost goading on the central character's tormenting behavior, to the extent that you'd be forgiven for assuming Phil's banjo performances were an integral part of Greenwood's composition.

Campion shot the film in her native New Zealand, with cinematographer Ari Wegner helping to transform the country's rural landscapes into a fitting stand-in for the Old West. The film has been described as a western because of its setting, but is very much set after the period when the films of the genre's golden era take place; a period of time when the old way of life was dying, the invention of the automobile allowing a new generation to escape to the city, and chase finer prospects in life. This remains largely unspoken in the tension between Phil and Peter, but feels crucial — even as the teenager can escape to study elsewhere, he will always return to find a man concerned with tradition, tasking himself with the burden of passing down the skills (and, crucially, masculine behaviors) his mentor taught him to a generation that has no need for them.

"The Power of the Dog" is a rich, rewarding film. It may abandon all subtlety when it comes to exploring its characters, but is so elegantly constructed you can't help but find intriguing nuances upon looking closer. One of the year's best films, and the perfect introduction to Jane Campion's work for a mainstream audience.