Should Hollywood Be Resurrecting Actors With CGI?

Since 1959, when schlock auteur Ed Wood hired his chiropractor to finish the part of Bela Lugosi in "Plan 9 From Outer Space," Hollywood has grappled with the desire to bring long-dead actors into new films. In 1982, several years after franchise star Peter Sellers died, "The Trail of The Pink Panther" took unseen footage of the actor intended for an unproduced feature and wrote an entire film around it, supplementing it with clips of a new actor disguised as Sellers (or with his face obscured). The studio went to great efforts to assemble the Frankenstein of films, all in an effort to be able to market a new Pink Panther film as starring Peter Sellers, which lead to a lawsuit. Bruce Lee was likewise repurposed — using even more crude and transparent effects attempts — years after his passing for 1978's "Game of Death."

As special effects technology has advanced, the resurrection of dead stars has become even more prevalent and expanded to more than walk-on parts. By the 2000s, CGI was good enough that entirely new performances could be created in a computer using the likeness of Laurence Olivier, Oliver Reed, and others. Most recently, Harold Ramis was recreated for a pivotal scene in "Ghostbusters: Afterlife." But just because Hollywood can bring back its biggest lost stars doesn't mean it should. Whether bringing back a dead actor is a moral or ethical question, a rights issue, or just a question of what's best for the future of the industry, there are a number of issues for this ever more disturbing digital trend. Scroll on and read what concerns us most when it comes to resurrecting dead actors on screen through the use of computer-generated imagery.

Whose permission is really needed?

Whether a new film's narrative makes resurrecting an actor natural to the story or whether it's just a shameless commercial cash-grab, studios need to get permission from the actor's estate or surviving heirs. But there's still a lot of legal murky waters here, particularly with regards to actors dead for decades, and that problem will only get worse as time marches on. Of all people, comedian Bill Cosby helped push efforts to change some of those laws as recently as 2012. But restrictions and allowances for a dead actor's likeness — particularly those that may one day enter the public domain — are still a sticky legal quandary. And there's a case to be made that until the law is rock solid, or unless stars themselves create provisions for the use of their likeness after death, such digital reprisals should be strictly limited.

Even for the recently deceased, actor likeness rights may not rest with the family in question, but with non-familial estates or licensing agencies like Authentic Brands Group — the agency that owns and controls the rights to deceased celebrities like Elvis Presley and Muhammad Ali. And when the primary focus is the bottom line, there's no telling how protective an agency will be or if they will truly have the actor's legacy and best wishes at heart. Sure, some executives may be protective of the star's brand and integrity, but even if they do care about what the actor may or may not have wanted, there's ultimately no way to know for certain. Even if the star's heirs, estates, or trusted agencies do give permission, it's often hard to watch a dead actor reimagined as CGI and shake the feeling that they've been dredged up from the grave against their will.

Does it disrespect the dead?

When a studio looks to bring back a dead star through visual effects, it's usually well-intentioned. Sometimes it's to continue the actor's role as an homage to what came before. For example, in 2006's "Superman Returns," Marlon Brando was recreated to reprise — albeit briefly — his part as Superman's Kryptonian father. Other times, it's to pay tribute to a lost star, as in "Ghostbusters: Afterlife." Whichever the case, audiences may wonder if the mere act of bringing back a dead star is disrespectful to those who never gave direct permission for such use before their passing.

It's hard to fault filmmakers for using CGI to finish an actor's performance following a tragic and untimely death during production, as we saw with Paul Walker in "Furious 7." In the case of a surviving loved one giving permission to the filmmakers for other reasons, we should trust that they know best, both for themselves and for their lost family member. Grief can be a long process, and if allowing their late spouse, parent, or child to reappear through the magic of CGI brings them peace, comfort, or even just a little financial security, perhaps it's best to accept that decision. Still, as critics and fans, it can be hard not to try answering the moral and ethical question ourselves because the thought of a greedy estate dishonoring the memory of a lost star is sometimes too heinous a concern to ignore. Because ultimately, the inclusion of CGI representations of deceased stars, even if well-intentioned by the filmmakers and family members, can come across as manipulative and creepy. Indeed, it can feel like a ploy to play off the audience's love of nostalgia to elicit a positive fan reaction to seeing their favorite dead heroes.

Is permission even enough?

Even if the legal questions are settled, contracts are honored, and permission from the surviving family is granted, some wonder if that's enough to allow for a dead actor to be resurrected via CGI. To many, the recreation is simply unethical, even if the star themselves allowed for the eventuality in writing before their death. To these critics of CGI actors, bringing back dead actors is simply disrespectful and classless, and there's no better example of this than when actors are brought back to appear in TV commercials hawking all manner of commercial products, becoming little more than a digital pitch-man.

Whether that's Audrey Hepburn selling chocolate or Fred Astaire dancing with a vacuum, critics see the recreations as cheaply leveraging a dead actor — sometimes against their will. When Johnnie Walker resurrected Bruce Lee to sell its Blue Label whisky, many of his most ardent fans pointed out that the martial arts legend was not a drinker. And while his heirs insisted he didn't have a dislike of alcohol, it still left a bad taste in the mouths of many, who felt it was a disgrace to his legacy to drag him out of the grave to become a run-of-the-mill advertisement. Elsewhere, Astaire's wife ardently defended the decision to permit the company to use her late husband's image, but that didn't stop many from calling it disturbing. No matter which side of the fence you stand on — approving of the practice or condemning it — it's hard to wonder if stars like Bruce Lee and Fred Astaire are better off left remembered as they were in the films they left behind.

Does it hurt Hollywood?

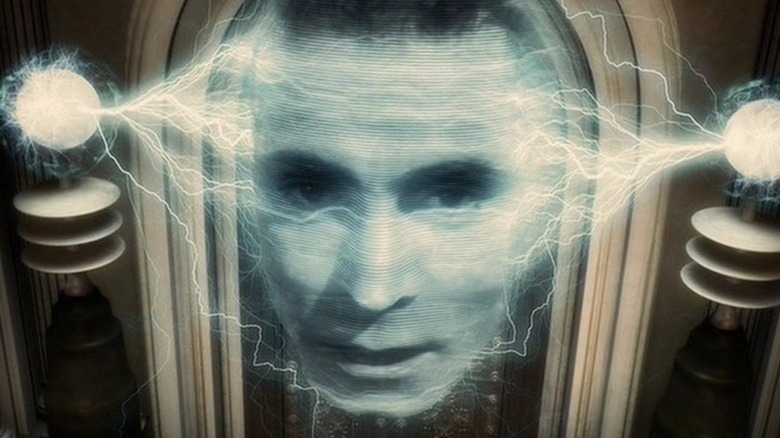

More than the ethical issues, there's another matter to be considered — the effect that pervasive digital resurrections could have on Hollywood as an industry. Consider a film like "Rogue One: A Star Wars Story." While the inclusion of Grand Moff Tarkin may have made sense to the story," necessity is the mother of invention, and if Disney had been unable to resurrect Tarkin, it might have been forced to find more creative solutions. Perhaps it might have created a new exciting character and cast a fresh lesser-known actor who could have parlayed the work into a bigger career. And while established actor Guy Henry performed the motion capture for Tarkin, what will happen when AI gets good enough that we don't even need stand-ins or voice actors, and directors can control computer-generated dialog and performance of a life-like digital actor with the click of a button? When you can recast Harrison Ford, Mark Hamill, and Carrie Fisher to play their original roles as their younger selves, there will be no need to hire new actors as they did for "Solo: A Star Wars Story."

In the future, if Hollywood could simply recreate a young version of a dead star, why cast anyone new? If an actor dies between sequels, there may be no need to thrust a new star into the limelight if they can simply recreate the original actor. If older stars can continue to look younger, and the day comes when dead ones can be resurrected with ease, there may be no need for new actors at all. That may sound like paranoid fear-mongering, but there really is no telling what the future holds.

Should there be more limits?

With the legal issues surrounding using the likeness of a dead actor being as complicated as they are, and outcry over digital actors growing, the industry may one day reach an impasse between actors, filmmakers, and studios. Given all the legal, moral, and ethical questions — as well as the problems the practice could create — we wonder if there should be limits placed on the use of dead actors in new roles through the use of CGI. This could mean a limited amount of screen time, limits on dialog, and restrictions on how those actors can be used — perhaps limited only to reprising old roles. Nevertheless, if the CGI resurrection trend continues and roles for deceased actors continue to grow, the default position might be a restriction.

There are many forms we could discuss, but one easy restriction that could be established is that no actor can be repurposed after their death unless the actor specifically says otherwise while alive. We've already seen some actors put such restrictions in writing — most notably Robin Williams before his tragic passing. The fact that Williams felt the need to be so crystal clear about his post mortem wishes tells you how fraught with problems the issue is. Perhaps there should be a provision in every actor's agreement with the Screen Actor's Guild upon joining where they can stipulate the limits (or lack thereof) on the use of their likeness after their death. Whatever the solution, the controversy over resurrecting actors with computer effects is not going away and will only get worse as technology and artificial intelligence continues to improve.

Will audiences continue to embrace it?

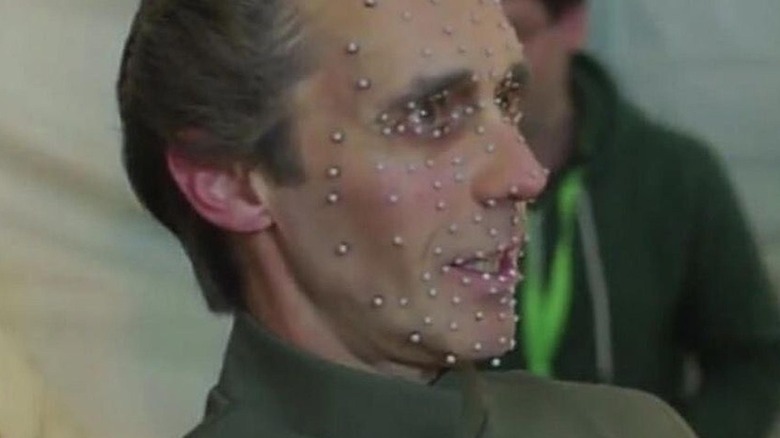

In the earliest days of Hollywood co-opting the dead to appear via CGI, opinions were split. While there were vocal critics, many applauded the new technology for the wonders it could create and were happy to see beloved lost stars once again on the screen, whether it was a cameo in a new movie or shilling for a new product in a television ad. But as the technology has advanced, CGI actors are gaining bigger and bigger roles, including four full minutes of screen time for Peter Cushing's Grand Moff Tarkin in "Rogue One." This trend will peak in the upcoming film "Finding Jack," which is controversially giving James Dean (who died in 1955) a starring role. Indeed, it remains to be seen if audiences will continue to cheer for dead actors brought back with CGI as their roles increase in size and importance.

Even in the 1980s, the appearance of the first colorized movies caused controversy, and in 1997, George Lucas' special editions of his original "Star Wars" trilogy — with digital restoration and newly shot footage — angered long time fans and raised the ire of film historians. When Coca-Cola added digitally enhanced footage of Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, and Louis Armstrong to a Diet Coke commercial starring Elton John, there were loud critics of the move, including some who felt it portended a dark future for the use of dead actors. It appears that their fears have turned out to be been well-founded.

Is it even necessary?

Though the digital trickery can be an impressive, incredibly convincing, and breathtaking visual marvel, some question whether bringing back a dead actor through CGI is even necessary. Recasting roles with new actors and replacing dead stars with living ones for sequels has been going on long before the implementation of CGI. Whether that's James Bond being recast a half dozen times or Richard Harris replacing Michael Gambon as Dumbledore in the "Harry Potter," audiences have shown a willingness to accept and even embrace a new actor, even in a role played by someone who has died. In the case of Laurence Olivier in "Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow," there was seemingly no reason to recreate the dead icon as the face of the film's villain, especially when the movie's target audience of kids and teens would likely not have recognized him. And after resurrecting the likes of Jack Lord for a 2016 episode of the new "Hawaii Five-O" or Peter Cushing for "Rogue One: A Star Wars Story," many have questioned whether the appearance of the revived CGI actors was really necessary to those stories and films. In fact, some believe they might have been better off without them.

In the film "Yesterday," when a man wakes up in a world where The Beatles never existed, actor Robert Carlye was hired to play an older John Lennon who was not assassinated in 1980. Through the use of heavy makeup and a strong performance from Carlyle that closely mimicked the famous Beatle, producers avoided the use of CGI. Had they opted for some kind of computer deep fake, it would have certainly created a controversy that could have taken away from the emotional weight of the scene.

Where do we go from here?

What started in a 1990 Diet Coke commercial expanded into the nearly entirely CGI film "Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow" and grew into the likes of "Ghostbusters: Afterlife." Now we are living in a time where seemingly any person, living or dead, can be created and recreated, aged to infirmity, or de-aged to their youth. And it's now leading us inexorably towards a digital future that could be both wondrous and terrifying — a future where audiences may not be able to tell who or what is real and who is a digital recreation. The legal questions at play are going to grow, and the ethical and social ramifications will take center stage. While the imaginations of our greatest filmmakers may be fully unleashed and unfettered by the practical limitation of death itself, the actors of the forthcoming generations may find new competition in past generations' biggest stars.

However Hollywood moves forward from here — should it decide to change the way actors are brought back with CGI or not — the future of digital actors based on real ones will need to be based on collaborations between actors, filmmakers, and studios. As the opportunities and technologies grow, decisions regarding the expanded use of dead actors will also need to be made in good faith for the longevity of the industry and the legacies of the actors themselves rather than for the art, films, or bottom line.