The Untold Truth Of Monty Python And The Holy Grail

"Monty Python and the Holy Grail" — it's a fitting name for a movie that itself has become a holy grail of cult comedy. Even people who have never seen or heard of the "Monty Python's Flying Circus" series or the group's two follow-up movies can quote huge chunks of the script verbatim: "What is the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow?" "I'm not dead yet!" "We are the Knights Who Say 'Ni!'" "Let's not go to Camelot. It is a silly place," "Just a scratch," and so on. Reinventing the legendary quest of King Arthur (Graham Chapman) and his knights for the goblet Jesus drank from at his Last Supper as a series of surreal and gory misadventures, "Monty Python and the Holy Grail" was a sleeper hit that's only become more popular as contemporary blockbusters are forgotten. It may have even changed our whole view of the Middle Ages, replacing the exaggerated splendor of a mythical age of chivalrous heroes with a vision of equally exaggerated grime and squalor.

As much fun as "The Holy Grail" is to watch, the quick, cheap production was anything but. Fortunately, it's just as entertaining to experience secondhand as the movie itself. Here are a few of the Pythons' strangest stories from the set.

Rock legends bankrolled Monty Python and the Holy Grail

As little money as Monty Python had to make "The Holy Grail," it came from a surprising source. The Pythons supplemented their TV series with record albums, usually bearing self-deprecating titles like "Monty Python's Contractual Obligation Album," "The Hastily Cobbled Together for a Fast Buck Album," and "The Monty Python Matching Tie and Handkerchief," a unique "three-sided album" that would play a different set of sketches depending on where you dropped the needle.

Monty Python produced these albums for Charisma, a company that mostly focused on pop and rock acts. As star Eric Idle explains in "The Pythons by the Pythons," this brought them to the attention of some true legends in the field, including Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, and Genesis. This acquaintance was profitable for all involved when Monty Python's labelmates helped put up the money for the team's first all-original movie.

It's fun to imagine all these rock stars were fans, but co-director Terry Gilliam offered a more cynical explanation to The Guardian. At the time, British taxes could take as much as 90% from high earners, and Gilliam said, "We seemed a good tax write-off. Except, of course, we weren't. It was like 'The Producers.'"

The Pythons lost access to their locations just before filming started

Trouble started on the set before filming could even start. In "The Pythons by the Pythons," directors Terry Jones and Terry Gilliam say they spent two weeks touring "every castle in Britain" to find shooting locations. Everything seemed to be ready to go until, just a week before they were scheduled to begin filming, the Department of the Environment for Scotland contacted them. They'd gotten wind of the Pythons' plans and withdrawn permission to film because "Holy Grail" was "not consistent with the dignity of the fabric of the buildings." Jones' thoughts on the decision shouldn't surprise anyone who's seen the grim view of the Middle Ages on display in the film: "These places had been built for torturing and killing people, you couldn't do a bit of comedy?"

So the Terries had to scramble to find some privately owned castles, and they ended up with just two — Castle Doune and Castle Stalker, which ended up standing in for all the many castles Arthur and his knights travel through. That includes Camelot — that's right, it isn't only a model!

Filming was so miserable even the camera wouldn't cooperate

The production didn't improve any when filming began. The very first day, the cast were all in costume to film the Gorge of Eternal Peril scene in Glencoe, Scotland. It was already looking to be a miserable day, shooting on a sheer cliff with wool "armor" that didn't agree at all with a wet climate. Even Chapman, an experienced mountain climber, panicked when he had to cross the rickety Bridge of Death.

And then the camera literally fell apart. In the documentary "Monty Python: Almost the Truth," production manager Julian Doyle describes the lightweight camera he'd jerry-rigged for the difficult shoot. But once it came time to use it, Jones recalled, "The cameraman said, 'Hey, wait a minute, something's gone wrong.' He opened up the camera and all the gears fell out." It was the only sound camera on the set, so while the Terries dispatched Doyle to fix the camera, they had to find different scenes they could shoot silent. Unfortunately, none of those fit into the bridge sequence, and according to "The Pythons," they had to spend the next hour just getting to the other side of the gorge to continue filming.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail had unexpectedly artsy influences

In many ways, "Holy Grail" is a classic of lowbrow comedy. Most of the jokes rely on simple pleasures: Silly voices, sillier puns, and people getting hurt. But it's also a surprisingly artful film, with first-time director Gilliam showing off the bona fides that would eventually lead to a career making classics like "Brazil" and "12 Monkeys." The crew all describe themselves as amateur medievalists, and they sneak in a surprising number of historical in-jokes and unexpected realism.

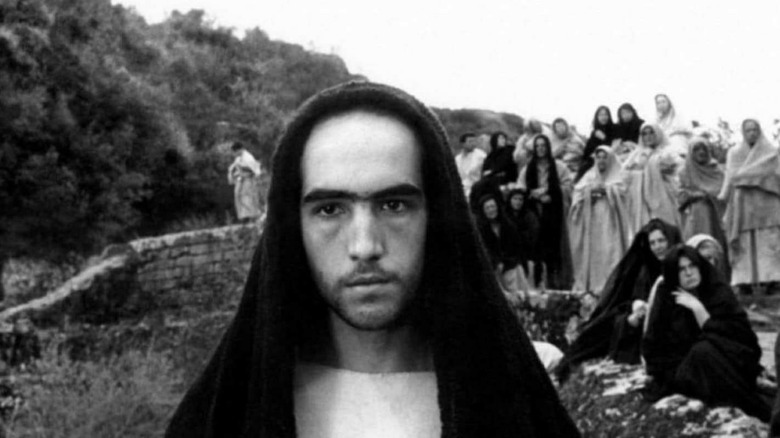

Even with all that in mind, it's still a shock to learn where the Terries went for inspiration on the look of the film. "Both Terry and I were very keen on Pasolini's films," Gilliam says in "Almost the Truth," "because they were always done in real places. You could smell them, you could feel it in the textures, the sounds and everything were all real."

Pier Paolo Pasolini was, indeed, very concerned with realism, since he came up as a screenwriter in the Neorealist movement of postwar Italy. As he began directing his own films, Pasolini took the same techniques his contemporaries used to capture ordinary life and applied them to historical subjects, including adaptations of "The Gospel According to Saint Matthew," "The Canterbury Tales," and "The Arabian Nights." No matter how far off the settings were, Pasolini always rubbed viewers' faces right in the middle of them — and in his infamous take on the Marquis De Sade's "Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom," maybe too close for comfort.

The mud-eating scene substituted chocolate -- in theory

Before Arthur can begin his quest, he and his squire Patsy wander the countryside in search of knights to join him at Camelot. Along the way, he meets Michael Palin as a literal dirt farmer who turns out not to work for any knight and instead lectures him on the superiority of anarcho-syndicalist government to monarchy.

According to "The Pythons," Palin's performance required him to crouch in "filthy, stinking, pig-*****y mud" for hours on end and, at one point, actually stuff some in his mouth. The propman assured him it would be fine, though: He had dropped some chocolate in the mud pile for Palin to eat. There were a few problems with that plan: First, there's no way to drop a pile of chocolate in the mud without it getting mud all over it. Second, Palin remembers, "I said, 'How will I know which is the chocolate and which is the mud?' They had no answer to that."

He remembers getting a little bit of each down his gullet — and then having to start over again because he had his back to the camera. He didn't take the revelation well, staging a tantrum so elaborate his castmates spontaneously broke into applause. Once he finally finished, Palin ran down to the nearest surgeon in a tiny Scottish village for a tetanus shot, still dressed in rags and covered in crud, to the doctors' confusion.

A one-legged silversmith stood in for the Black Knight

Later, Arthur tries to recruit the Black Knight (John Cleese), who refuses to let Arthur cross his bridge without a fight. Arthur wins pretty effortlessly, chopping off all the Black Knight's limbs one at a time. But, insisting it's "just a scratch," the Knight doesn't know when to give up.

No one would confuse "Holy Grail" for a special effects spectacular, and for the most part, this scene is no exception — you can just see Cleese's arm under his shirt after it's supposedly hacked off, the blood is awfully thick and opaque, and he pretty obviously turns into a puppet by the end. But the Pythons were lucky enough to stumble into some verisimilitude for one shot. In "The Pythons," Cleese reveals that the crew recruited Richard Burton to stand in for him once he loses his leg. To be clear, we don't mean they scored a cameo from the star of "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf" and "Cleopatra." This Richard Burton was just a tinsmith from London. But he really did only have one leg.

Playing Tim almost killed John Cleese

It should be obvious by now that the Pythons were willing to suffer for their art. And if many of them are still alive almost 50 years later, it's not for lack of trying. Cleese, specifically, had a close call playing Tim the Enchanter. The role required him to stand on a mountaintop and set off fireballs all around him.

The explosions spooked Cleese badly enough, but then he saw the mountaintop was a much bigger threat. In "The Pythons," he remembers, "I realized, really to my alarm, that there was a drop on one side that would have killed me and a drop behind that would have maimed me." His elaborate costume only made things deadlier, since the cloak formed a giant kite for the wind to nearly send him sailing off to the rocks below. "I had to wait up there for forty-five minutes, and I was crouched at the top of this pinnacle just trying to present as small a target for the wind as possible," he recalls. "I remember Terry shouting 'Are you alright?' I said, 'No, what are you going to do about it?'"

Terry Gilliam recruited tourists for the final fight

One side effect of location shooting was it kept the Pythons close to their public, sometimes with surreal results. Palin writes in "The Pythons," "We were all in chain mail and driving this van to the location ... I remember people going by on the other side of the road, because it's quite a tourist spot, and just doing the biggest double takes of all time, necks would snap as they saw these knights driving their Ford Transit van up to Glencoe."

Some of the passers-by even ended up in the movie. In "Almost the Truth," Jones reveals he wanted to get some shots of the army charging at Castle Starker while they were there, but they wouldn't have the costumes ready for another five weeks. They were still able to get the shots, but a lot of trickery was involved.

Gilliam explains, "We got everybody, everybody's child, everybody who's around, to hold up banners and pikestaffs in front of the camera — a few helmets we had, so you see those — and we set up very, very carefully, and you'd swear there's an army there."

The first draft ended with a Grail heist

"Holy Grail" has a famously abrupt ending, as the team of modern-day police who had been investigating Lancelot's murder of "a very famous historian" suddenly arrive to arrest the entire cast and the film smash cuts to black. But earlier drafts of the script had much more conventional and elaborate endings planned before reality set in. In "Almost the Truth," star Eric Idle remembers the first draft, which ends with King Arthur finding the Holy Grail in the grail department of Harrod's Department Store.

In "A Book about the Film Monty Python and the Holy Grail" Darl Larsen goes into more detail on the alternate ending. Arthur grabs an armful of grails and brings them to God in the coffee shop. None of them please Him, and he demands Arthur find "the true Grail," which is "somewhere in Italy." "Somewhere" turns out to be a church, which God, Arthur, and the knights speed away from in a VW van, pursued by gun-toting priests. They drive straight into the ocean as God promises to part the waves for them. He fails, and the van sinks.

This ending proved impractical, and not just for budget reasons. Monty Python would stir up worldwide controversy for their follow-up film, the passion-play parody "Life of Brian." If they got in that much hot water over a character they repeatedly insist is "not the messiah," how much more trouble would portraying God Himself as an incompetent church robber land them in?

Terry Gilliam snuck into the studio to re-edit the film

Even after filming wrapped, the troubled production of "The Holy Grail" continued. Splitting directorial duties between two fiercely opinionated men who'd never made a movie before was never going to be a smooth process, and the clash of personalities came to a head over the edit. In "Gilliamesque: A Pre-Posthumous Memoir," Gilliam reveals that both he and editor John Hackney were so unhappy with the direction in which Jones was taking his cut that they'd sneak into the studio at night to redo it behind Jones' back. They were never caught, but as Gilliam puts it, "my comeuppance was just around the corner" anyway.

The first screening of "Monty Python and the Holy Grail" was a disaster. In "Almost the Truth," Jones remembers it opening promisingly with the audience laughing themselves sick over the "Bring out your dead!" scene (which opened the rough cut) — and then never again for the rest of the evening. The blame went on Gilliam and his nocturnal edits. He admits, "I was so intent on a realistic atmosphere that I'd over-egged the sound effects to the detriment of the dialogue." That wasn't the only sound issue. On their meager budget, Neil Innes' score couldn't conjure up the parodic bombast the movie needed. Fortunately, the crew found an even cheaper solution, cobbling together a new score from stock music cues. In the end, it took 13 edits before they finally hammered "Monty Python and the Holy Grail" into shape.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail premiered with a coconut giveaway

"Monty Python and the Holy Grail" finally reached theaters accompanied by a promotional gimmick in line with the movie's surreal sense of humor. "The Pythons" includes a poster advertising 1,000 coconuts for the first 1,000 patrons to arrive at the film's premiere at the Plaza Theater in New York, in tribute to the shells that stood in for Arthur and his knights' horses. It worked a little too well as Idle writes, "We were called up in the hotel and they said there's already a thousand people outside lining up at 8 in the morning." He adds, "When they came out, we'd have to autograph the coconuts ... which is an impossibility."

For all that, it was an appropriate tribute to the gag — an image of Patsy trailing behind King Arthur, banging the coconuts together — that inspired the whole film. Gilliam adds that the film's low budget prevented them from trying to use actual horses, which worked in their favor. "We would never have got through that movie with real horses," he writes. "It makes a wonderful leap because with that opening shot you accept the kind of lunatic logic that's there."

Monty Python and the Holy Grail was Elvis Presley's favorite movie

"Monty Python and the Holy Grail" became a surprise hit, but it's even more surprising to learn some of the people it scored with. Somehow, this very British movie found its way into the heart of the ultimate American rock star. In "Almost the Truth," Python historian Robert Ross says that Elvis Presley screened "Holy Grail" 45 times at Graceland, his home in Memphis. Elvis was already ahead of the curve on Monty Python — in "The Pythons," Idle remembered being "bowled over" when he learned the King of Rock and Roll had started calling people "squire" after seeing the classic "Nudge Nudge" sketch on "Flying Circus."

Either way, it's a surreal image to imagine Elvis obsessing over this dorky cult comedy. His friend Jerry Shilling even remembers him pulling out a perfect imitation of John Cleese as the Black Knight saying, "Just a scratch" when he injured himself playing football. As comedian Phil Jupitus puts it, "Just the idea of Elvis knowing those catchphrases and him being as annoying as my little brother as well..." — he can't even finish that sentence without cracking up.