The Ending Of The Unforgivable Explained

In Netflix's "The Unforgivable," director Nora Fingscheidt tries to shine a light on the obstacles former convicts face when they attempt to re-enter a society whose laws and accepted definitions of right and wrong they've defied. The film hit theaters in limited release on November 24 before coming to the streaming service on December 10 and was produced by lead star Sandra Bullock's Fortis Films. An adaption/condensed version of Sally Wainwright's critically-lauded three-part miniseries, "Unforgiven," the film also stars Hollywood heavy-hitters Viola Davis and Vincent D'Onofrio, as well as rising star Aisling Franciosi (of "The Fall" and "Game of Thrones").

While the first two-thirds of the film play out like an exercise in character development and social commentary, the final third transitions into the kind of '90s suspense thriller that might have starred someone like Ashley Judd, Robert Downey Jr., or, well, Sandra Bullock. Although it received more than a little criticism for its confused focus and rushed/all-too-convenient plot turns (see: The Guardian and Roger Ebert reviews), the film's ending brings its original intentions into relief.

The Unforgivable gives audiences two films in one

At the start of the film, Bullock's Ruth Slater is released from prison after serving 20 years for killing Sheriff Mac Whelan (W. Earl Brown) during his and his officer's attempt to evict Ruth and her five-year-old sister Katie from their home. We learn through flashbacks that with their parents both dead, Ruth had to become Katie's caretaker, and in her chaotic and desperate attempt to prevent the child from being taken away along with their home, Ruth made a violent stand. Society is unforgiving to Ruth, who never attempts to explain her actions, and her release into society is plagued by verbal and physical abuse, lost opportunities, and pre-judgment from people who know nothing about her aside from her conviction. Despite these difficulties, Ruth never loses sight of her only goal: to reunite with, or at least learn something about the fate of Katie.

Eventually, Ruth convinces Attorney John Ingram (D'Onofrio) to help her in her quest to see her sister, who's been living with an adopted family since Ruth's conviction and has only fleeting, incomprehensible memories of what occurred in her previous life. Just as she's on the cusp of being able to see Katie (at least from afar), Ruth is lured into a trap by the son of the sheriff she killed all those years ago, and the film switches into thriller mode. Though the premise is somewhat split, both halves of the film attempt to speak to the same issue.

The Unforgivable attempts to explore the racial gap in society's sympathies for the convicted

Throughout the film, it's difficult not to have sympathy for Ruth. As her parole officer Vincent (Rob Morgan) warns her, no matter where she goes, she's nothing more now than a cop killer. But aside from the fact that she's treated exceptionally poorly by society upon her attempted reentry into it (at one point, one of her co-workers even beats her to a pulp), there's nothing in Ruth's actions, words, or explanation of events (or lack thereof) that actually earns her any sympathy. Instead, the viewer's willingness to take her side comes from a combination of the accepted language of cinema — the camera is following Ruth, so, it's Ruth with whom we sympathize — and, whether audiences want to admit this or not, the perception that she "doesn't look like" a killer. In other words, despite the filmmaker's best attempts to make Bullock look weathered and rough around the edges, she's still Sandra Bullock: a conventionally attractive, white female protagonist.

This isn't lost on the story's intentions. In one of the film's more compelling scenes, the matriarch of the family living in Ruth's former home — Liz Ingram, portrayed by Viola Davis — calls out this unwarranted empathy. Liz's husband John is the attorney who takes pity on Ruth's plight, but as Liz points out to her white husband, if the criminal in question had been Black, this wouldn't even be a conversation. "If your Black sons had been in this situation," she says, "they'd be dead."

Although the film, unfortunately, never fully embraces any exploration of this discrimination, the short scene acts as an important caveat to one of the film's overarching themes. While the first half of the film questions society's unwillingness to allow former convicts to rejoin society even after they've served their time, it's clear that even when that willingness does manifest, it's almost exclusively granted to white women.

The Unforgivable pivots on the point it has to make

In the end, "The Unforgivable" gives both Bullock and the viewer an out (perhaps to its own detriment). In another far-too-short Viola Davis scene, Ruth and Liz get in an argument wherein the latter refuses to help the former, explaining that she made her choice and that it's her own fault she's in the situation she's in and unable to see her sister. In the scene, we learn via flashback that Ruth didn't actually kill the sheriff. During her aggressive and frantic defense of her home, the then-5-year-old Katie heard her big sister tell the police that she had a gun in the home, and was prepared to use it if they came inside. When the sheriff did manage to make his way in, it was Katie — not Ruth — who shot and killed him. Despite the fact that no jury in its right mind would (or even legally could) convict a 5-year-old of murder, Ruth takes the fall for Katie in order to protect her.

This explanation of events convinces Liz to help Ruth get to Katie's recital, vindicates the audience's already-established (if not totally earned) sympathy, and instantaneously redeems Ruth as a character for any viewers who weren't already in her corner. Presumably, it's the film's way of questioning the assumptions we make about former convicts, particularly when we don't know all the circumstances or facts of a given case. Rather than fully embracing its initial "sympathy for the devil" storyline, the film makes a major pivot, and the protagonist's redemption comes not from some lesson learned or some major sacrifice made, but from the fact that she was never actually a killer to begin with.

The sacrifice was made years ago, by a caring and over-protective sister terrified of what might happen to her young charge. The film, having completed the social commentary narrative of its first part, then pivots once more, landing on an ending that has less to do with redemption and more to do with the cyclical mechanics of violence.

The Unforgivable's ending splits the difference in its themes

En route to Katie's recital, Ruth gets a call from Steve (Will Pullen), one of the sons of the man she went to prison for killing. Following a series of events that led him to snap, Steve resolves to get revenge on Ruth for killing his father, and, in his mind, ruining his and his brother's chance in life. Though he's actually kidnapped Katie's adopted sister Emma (Emily Malcolm), Steve believes he has kidnapped Katie. He lures Ruth to come to her rescue where he'll be able to avenge his father's death by killing her.

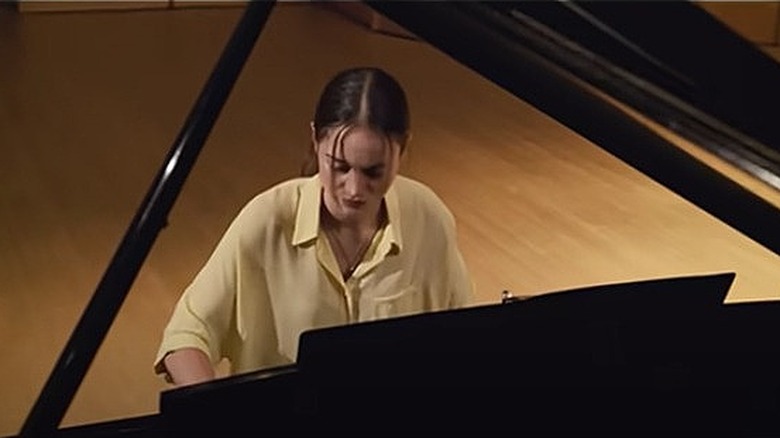

In one of the few subtle moves made by "The Unforgivable," while Ruth is being lured into a rescue mission, Katie is safe and sound at her recital and expertly tackling a piano-only version of Radiohead's "Everything In Its Right Place." Though the song leaves itself open to a litany of interpretations, it's clear the filmmakers focused on how its title might serve to punctuate the subtext of its finale. Everything ends in its "right place" when Katie and Ruth are reunited, and the two finally embrace following Ruth's successful rescue of Emma. But there's a second idea of "place" or order pointed to in the film's finale — that is, that violence follows (and/or is birthed by) violence. Steve wants to kill Ruth, simply because he believes Ruth killed his father. That the two characters have faced similar struggles over the years — and that they have more in common with regard to their poverty-begotten circumstances than Steve realizes — takes a back seat to his compulsion to retaliate.

Whether or not the film's divided genre focus and sped-up storyline successfully accomplish its goals or not, the ending of "The Unforgivable" illustrates its attempt to investigate both the cyclical nature of violence and incarceration and the ease with which society ignores those factors in its black-and-white judgment of those who commit violent acts.