Characters You Thought Stan Lee Created But He Actually Didn't

Stan Lee is responsible for a huge chunk of the Marvel Universe—but not all of it. Not only did Lee rely on talented artists like Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, and John Buscema to bring characters like the Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, and the Incredible Hulk to life, but as Marvel's superhero line expanded, so too did its roster of creators, many of whom dreamed up characters with minimal input from Stan the Man.

That hasn't stopped Mr. Lee from cameoing in practically every project with a Marvel Studios logo slapped on it—hey, Stan's gotta eat—but don't get the wrong idea. The Marvel Universe wouldn't exist without Stan Lee, but he's far from the only person responsible for its success.

Captain America

That's right: Captain America, Marvel Studios' standard bearer and the so-called "First Avenger," was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby while Stan Lee (then going by his real name, Stanley Lieber) was still an assistant. "I went down and got them their lunch, I did proofreading, I erased the pencils from the finished pages for them," Lee later recalled. Meanwhile, Simon and Kirby were hard at work creating a hero that would both capitalize on the growing superhero craze (Action Comics #1, which introduced Superman to the world, sparked a slew of imitators when it came out in 1938) and make a defiant statement about the real-world political scene.

"We both read the newspapers. We knew what was going on over in Europe," Simon explained, and neither he nor Kirby were going to sit idly by as fascism spread across the continent. "World events gave us the perfect comic-book villain, Adolf Hitler, with his ranting, goose-stepping and ridiculous mustache," Simon said, and ol' winghead was originally designed to be Hitler's arch-nemesis. On the cover of Captain America Comics #1, Captain America punches Hitler right in the face—a bold move, given that America wouldn't formally enter World War II for another year.

Of course, over time, Lee did contribute quite a bit to the Captain America mythos. His first credited writing gig was a story in Captain America Comics #3, which sees Cap throw his shield like a boomerang for the very first time. Captain America's revival as a modern superhero, which began in Avengers #4 when Cap was found frozen in a block of ice, was a Stan Lee joint. But the original Steve Rogers? That was Simon and Kirby all the way.

Wolverine

The X-Men are one of Marvel's most popular and most profitable franchises, yet the series' undisputed star, Wolverine, wasn't originally created as one of Marvel's band of merry mutants. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby released X-Men #1 in 1963, introducing the world to Professor Charles Xavier, his students Cyclops, Iceman, Beast, Angel, and Marvel Girl, and the mutant terrorist Magneto. But the book wasn't a hit, and the series was canceled in 1970 after 66 issues.

So when Len Wein, John Romita, and Herb Trimpe created Wolverine in 1974 as a foil for the Hulk, he couldn't join the X-Men—there were no X-Men to join. Besides, Wein's pointed out, Wolverine wasn't created to flesh out the X-Men's roster. He was birthed from a challenge issued by editor-in-chief Roy Thomas. "He said, 'No, seriously, you write these great accents and I can't do accents,'" Wein recalled. "He said, 'I'd love to see how you would write a Canadian accent. I have the name.' The name was Wolverine."

Wein went home and researched wolverines, which he discovered are "short, really hairy, feisty animals with razor-sharp claws who are utterly fearless," much like Logan himself. With Wein overseeing, John Romita provided Wolverine's initial design, Herb Trimpe refined it, and the hero made his first appearance at the very end of The Incredible Hulk #180, with a featured role in The Incredible Hulk #181 (ironically, Wein thinks he ultimately failed to capture a Canadian accent—"I thought he ended up sounding more Australian in that story," Wein says, which might explain Wolverine's voice in the ill-fated Pryde of the X-Men pilot).

Of course, Wolverine's future tenure as an X-Man wasn't too surprising. Wein explained Wolverine's powers via mutation because he'd heard rumblings that Lee and other Marvel executives were considering a major revamp of the X-Men property. "I thought I would provide for whoever ended up writing that book," Wein said (of course, he ended up writing Giant-Size X-Men #1, which reinvigorated the franchise).

The Silver Surfer

From 1961 to 1970, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby produced 108 consecutive issues (102 normal installments and six annuals) of The Fantastic Four. And yet the Silver Surfer, who first appeared in The Fantastic Four #48—right smack dab in the middle of that record-setting run—is credited solely to Kirby. Lee's name is nowhere to be found.

There's a very good reason for that. In the '60s, Lee was writing more or less every book in Marvel's superhero line. In his own words, he couldn't write fast enough, and instead let his artists do most of the heavy lifting. "I would say to the artist, 'Look, this is the plot I want,' and I would either tell them in a few words what the story was or I would write an outline on a page or two pages, or a few paragraphs. And I'd say, 'You go ahead and draw it any way you want. It doesn't matter, I'll put the words in and tie it altogether.'"

Over time, that system became known as the Marvel Method, and it clearly worked out for both Lee and Marvel. It also led to some surprises. While Lee gave Kirby a general outline for Fantastic Four #48, which features the arrival of the world-consuming alien Galactus on Earth, Kirby added the Silver Surfer character on his own (reportedly, he was inspired by a newspaper clipping about Southern California's growing surf community). Lee had no idea that the character existed until he saw Kirby's finished pencils, at which point he tactfully asked, "Who the hell's this?"

Of course, as time passed, Lee fell in love with the Silver Surfer. Lee's 1967 Silver Surfer solo series, which was illustrated by John Buscema, is widely considered the most introspective and complex comic book work Lee ever produced, and went a long way towards cementing Norrin Radd's noble character. Lee didn't create the Surfer—that honor belongs to Jack Kirby alone—but he helped define him.

The Punisher

Lee wrote the first hundred or so issues of The Amazing Spider-Man (issue #110 was his last), and introduced hundreds of memorable characters along the way. By the time Amazing Spider-Man #129 hit stands, however, Lee was only involved in a supervisory capacity—meaning that the issue's big guest star, Frank Castle, isn't one of his creations.

Originally, Gerry Conway envisioned the Punisher as a foil not just for Spider-Man, but Spider-Man baddie the Jackal as well. Conceived as a one-off character inspired by the movies Death Wish and Dirty Harry, he was supposed to die at the end of Amazing Spider-Man #129 at the Jackal's hands. But Frank Castle's complicated morality made him both an effective superhero ally and also a cunning Spider-Man villain, while his skull costume (designed by Marvel stalwart John Romita, based on a concept by Conway himself and drawn in the comic by Ross Andru) made him hard to ignore, so Conway couldn't pull the trigger.

Still, while Conway was clearly the driving force behind Frank Castle's inception, Stan Lee did have one big influence on the character: Lee gave the Punisher his name. As the story goes, Conway wanted to name the character the Assassin, but Lee worried that the name was too negative for a kid-friendly comic book, and encouraged Conway to lift the name of one of Galactus' sidekicks instead.

Venom

Pretty much every big creator at Marvel in the '80s had something to do with Venom's conception—except for Stan Lee. It started when a fan named Randy Schueller sent a pitch to Marvel in which Peter Parker got a brand new, all-black "stealth" costume. Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter liked the idea so much that he paid Schueller $220 for the rights and introduced the new outfit in Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars #8, which was written by Shooter and drawn by Mike Zeck.

Originally, Spider-Man's new duds were just made out of self-repairing alien technology, but somewhere along the way, they got a mind of their own. Artist John Byrne claims he came up with the idea for a living costume while working on Iron Fist with Chris Claremont as a way to explain why Danny Rand's clothes repaired themselves between issues. Byrne never got around to using the concept, however, and writer Roger Stern asked to borrow it for The Amazing Spider-Man. Stern left Spider-Man before the concept was fully implemented, leaving it up to writer Tom DeFalco and artist Ron Frenz to establish the symbiote suit's unique identity.

Spider-Man ditched the black suit for good in Web of Spider-Man #1 (written by Louise Simonson and penciled by Greg LaRocque), while David Michelinie and Marc Silvestri brought it back as a mystery villain in Web of Spider-Man #18. After a couple years of teases, Venom finally made his full debut in Amazing Spider-Man #300, with Michelinie writing and Todd McFarlane handling the art.

Luke Cage

When Stan Lee laid the foundation for the Marvel Universe, he drew on popular stories, real-life politics, and big social trends to make his characters feel fresh and relevant. The Fantastic Four, for example, rushed into a flurry of cosmic rays in a prototype rocket in order to beat the Soviet Union in the space race. Tony Stark—the weapons manufacturer who'd become known as Iron Man—was created at a time when the comic-reading audience was anti-military and anti-war and Lee thought "it would be fun to take the kind of character that nobody would like... and shove him down their throats and make them like him."

Other Marvel creators followed suit. Iron Fist debuted just as kung-fu films were beginning to make their way west en masse, and in 1972, Stan Lee instructed his bullpen to create Luke Cage in response to blaxploitation hits like Shaft, Hit Man and Superfly. Like most blaxploitation heroes, Cage isn't a superhero. He's just a man trying to get by. "Stan didn't want a typical superhero name for the comic, [and] wanted him to want to make a paying career of crime-busting," Marvel's future editor-in-chief Roy Thomas recalled.

Luke Cage wasn't just a cynical cash grab, of course. In order to keep him as authentic as possible, Marvel recruited writer Archie Goodwin (who wasn't black, but had written a number of well-received black characters for rival publishers) to script, and had inker Billy Graham, who was African-American, tweak artist George Tuska's designs. "Graham was... instructed to make certain that George's African-American characters looked African-American," Thomas said. "I think there was always the idea... that Billy... might take over the penciling at some later stage when George was moved on to other things."

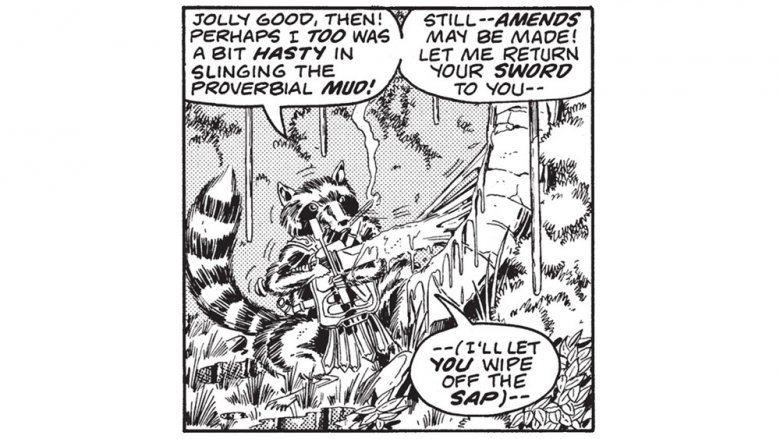

Rocket Raccoon

Believe it or not, but Stan Lee is only responsible for one of the Guardians of the Galaxy: along with Jack Kirby, Lee created Groot for Tales to Astonish #13, in which the hulking tree-beast from the stars plays the role of a typical monster movie villain. Groot's best buddy Rocket, meanwhile, is the progeny of Bill Mantlo, Keith Giffen, and—at least unofficially—the Beatles.

Yes, Rocket Raccoon's storied history is essentially just one long pop-culture reference. It's not subtle, either. In Marvel Preview #7, a black-and-white anthology series, a talking raccoon who goes by the name Rocky appeared briefly in a "Prince Wayfinder" story—obviously, that's a nod to "Rocky Raccoon," which appears on The Beatles' White Album.

When Rocket reappeared six years later in the The Incredible Hulk #271, the reference was even clearer. Mantlo titled the yarn "Now Somewhere In the Black Holes of Sirius Major There Lived a Young Boy Named Rocket Raccoon" (the Beatles song opens with the line, "Now somewhere in the Black Mountain Hills of Dakota there lived a young boy named Rocky Raccoon."). Rocket lives on planet called Halfworld with his friend Wal Russ (see also: The Beatles' "I Am the Walrus"), and protects its greatest treasure, Gideon's Bible.

That makes the character sound like a joke, but it was enough to get him his own solo miniseries in the '80s, which was written by Mantlo and drawn by a very young Mike Mignola. Later, he joined the Guardians of the Galaxy and, well, you know the rest.

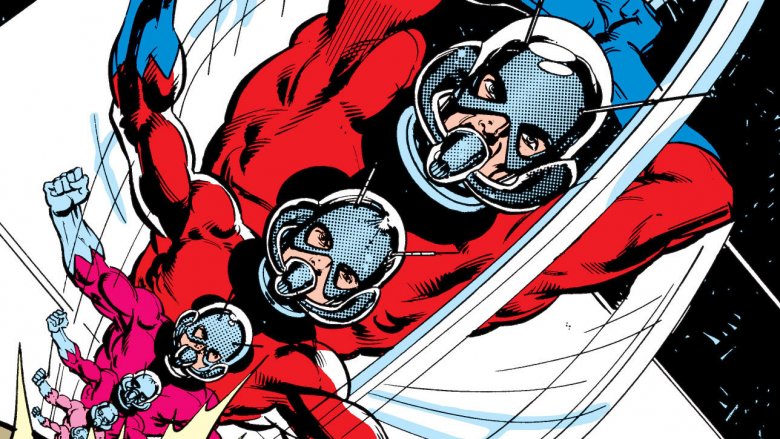

Scott Lang (Ant-Man)

Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, and Jack Kirby came up with the original Ant-Man, Hank Pym, who first debuted in Tales to Astonish #27 as a science fiction character, and reappeared as a superhero in Tales to Astonish #35. While Pym and his girlfriend, the Wasp, would anchor Tales to Astonish for a number of years and went on to become founding members of the Avengers, the character never caught on as a solo act.

To make matters worse, writers and artists constantly portrayed Pym in a less-than-favorable light. In The Avengers #54 through The Avengers #58, readers learn that Pym created Ultron, a murderous robot. In The Avengers #59 and #60, Pym changes his superhero identity to Yellowjacket, kidnaps the Wasp, and is diagnosed with schizophrenia. In The Avengers #213, he hits his wife and is expelled from the Avengers. Hank Pym has never recovered.

"Hank Pym had become an unstable, unlikable character," artist Bob Layton said. "I believe the mandate was to humanize the character of Ant-Man." Scott Lang fit the bill perfectly. As co-creator David Michelinie explained, Lang—an ex-con who stole the Ant-Man suit to support his family—is a classic Marvel character. "It was tough for a single father to fight crime while trying to raise a kid," Micheline said, "and it was tough for [his daughter] to know her father was a superhero and not be able to tell anyone."

That's certainly a more sympathetic character than an unbalanced super-scientist, and Marvel Studios knows it: when the company decided to bring Ant-Man to the big screen, they made Scott, not Hank, the hero, and the franchise is all the better for it.

Elektra

Stan Lee and Bill Everett created Daredevil in 1964, but while most of ol' Hornhead's supporting cast is intact, you can barely recognize Matt Murdock himself. Instead of a grim, angsty warrior, the early Daredevil is a wise-cracking, swashbuckling Spider-Man knockoff. Instead of facing off against crime bosses, drug dealers, and ninjas, he fights ludicrous villains like the Matador and Stilt-Man.

Daredevil didn't really become, well, Daredevil until Frank Miller started working on the book, starting as the artist for Daredevil #158 and taking over the writing duties in Daredevil #168. That latter issue is also, not coincidentally, when Matt Murdock's former lover Elektra made her very first appearance.

Inspired by the "Sand Seref" arc in Will Eisner's influential comic strip The Spirit (Miller says Daredevil #168 is more or less a straight-up remake of Eisner's tale, and side-by-side comparisons seem to validate his claims), Elektra represents everything that makes Miller's Daredevil run so exciting. She's the victim of an international terrorist attack and a trained assassin, fusing real-world conflicts with pulpy, over-the-top superhero action (she also dies 13 issues later, kicking Matt's character-defining guilt complex into overdrive).

In other words, it's easy to see why Elektra became a key part of the Daredevil franchise—and why it's so hard to get rid of her. Originally, Elektra was supposed to be a one-and-done character, but Miller couldn't help but bring her back for repeat appearances. After she died (again), Marvel promised Miller that Elektra would never be revived, but broke its word in 1993. As assistant editor Pat Garrahy explained, "[Editor Ralph Macchio] meant to keep his promise. But he made the promise when Marvel was a close-knit company, and Marvel the corporation had no intention of leaving Elektra an unturned stone."

Ghost Rider

The first Ghost Rider was a western villain who appeared in Ray Krank and Dick Ayers' 1949 comic Tim Holt #11, which was published by Magazine Enterprises. In 1967, Ayers took advantage of a lapsed trademark and unofficially revived the character for Marvel, hoping to capitalize on the popular country-western song "(Ghost) Riders in the Sky." The Ghost Rider you're familiar with didn't appear until 1972, when he debuted in Marvel Spotlight #5—and, unfortunately, nobody's quite sure who's responsible.

Thomas claims Ghost Rider started life as a motorcycle-riding Daredevil villain named the Stunt-Master, who writer Gary Friedrich wanted to revamp as "a really weird motorcycle-riding character." Thomas liked the idea so much that he decided to give Ghost Rider his own book instead. According to Thomas, Friedrich was out of the office when the Marvel bullpen designed Ghost Rider, and so creation duties fell to Thomas (who came up with the skull head and the outfit) and Mike Ploog (who set the whole thing on fire). From there, it was off to the races.

Or was it? According to Friedrich, the flaming skull and the rest of Ghost Rider's iconic look was all his idea, and he sued Marvel over the rights to the character in 2007 (he lost, and was forced to pay a $17,000 settlement). And Ploog says he doesn't really remember who created what, and that it doesn't matter anyway, because the modern Ghost Rider's design "was a ripoff of the old western one" anyway.

The only thing everyone can agree on? Stan Lee had nothing to do with the character—in fact, he didn't even cameo in Nic Cage's Ghost Rider flicks, making them two of the few Marvel-related projects that haven't featured his mustachioed face.