Things Only Adults Notice In The Adventures Of Sharkboy And Lavagirl

Nostalgia can be a strange thing. While many people operate on the assumption that everything was better when they were a kid, and today's entertainment isn't nearly as good, that isn't always the case. Sometimes, if you re-visit something with an open mind, you might be surprised to discover that the '80s movie you so fondly remember is actually slow an poorly-written, and that some recent reboot had more inspired ideas than you expected.

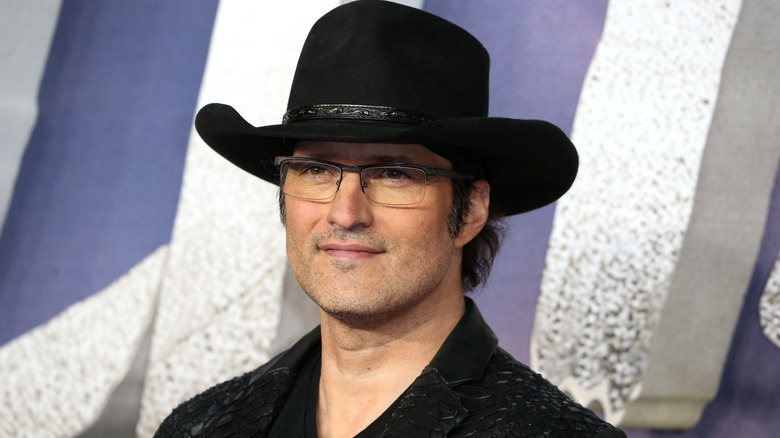

Other movies are wholly incomprehensible when you revisit them with a fully-grown brain, perhaps none more than 2005's "The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl." A labor of love, it was based on the dreams and imagination of director Robert Rodriguez's 7-year-old son Racer, who even receives a story-by credit.

The film was intended to be a reflection on the power of dreams, one that purposefully distorts the nature of reality within the film, even pre-empting a lot of questions adults might have about continuity and logical consistency; on some level, it was David Lynch for tweens. But even if you extend "Shark Boy" all the goodwill in the world, considering it something literally made "for kids, by kids," the movie remains a huge, confusing mess. These are the things only adults notice — often, out of confusion — when they watch.

Did Robert Rodriguez make this movie to torture other parents?

The opening titles of "The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl" declare it as a "Rodriguez family film," announcing the quasi-home-movie that it is. The story is "based on the dreams of Racer Max," his son who even plays Sharkboy in flashback. In the mid-2000s, Robert Rodriguez was arguably at the height of his powers, having successfully made the jump from "El Mariachi" wunderkind (he had shot his debut film for about $7000, much of it raised while participating in experimental drug trials) to commercially-friendly action filmmaker with the likes of "Desperado," From Dusk Till Dawn" and three "Spy Kids" films.

This is before films like "Grindhouse," Shorts" and a poorly-received "Sin City" took his star down a few pegs. Rodriguez had carte blanche to make this movie whatever he wanted it be — but if you were a parent in 2005, you may have been wondering if "Sharkboy" was some sort of prank.

Even the most inane, fart-humor-based kids movies will often add in some adult-targeted wit. "Sharkboy and Lavagirl," however, aimed squarely for the kids.

The adults in the movie, although capably played by household-name actors like George Lopez, David Arquette, and Kristin Davis, often deliver stiff, awkward dialogue that sounds like a 7-year-old wrote it. This could be considered a bait and switch, as kids looking for action-adventure received what was essentially a summer-camp-play-level-production, albeit one with a $50 million budget. For an adult expecting another "Desperado," "Sharkboy" represented a tough viewing experience.

What exactly is the takeaway about dreams?

According to its IMDb trivia page, the word "dream" (or some variation) is uttered one-hundred-and-eighty-eight times in "The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl." So, essentially it is "dreams" what "Scarface" is to the f-word.

By about the fiftieth time, it becomes entirely unclear what the movie has to say about dreams, other than "dreaming is good to do!" Max (Cayden Boyd) is mocked by his classmates for reading his dream journal about Sharkboy (Taylor Lautner) and Lavagirl (Taylor Dooley) to the class as "what I did this summer." But then, his dreams turn out to be real when they actually show up, so the bully kids learn that dreams are good because ... they can become real?

Then there's the matter of Max's parents. His father is an unemployed writer, and his inability to get a "real" job has pushed Max's mother to the brink of divorce. But rather than get another job — or at the very least convince her writing is noble enough to warrant being penniless — the pair have a discussion where they remind each other that they're best friends, reconciling without resolving the issue.

"Sharkboy and Lavagirl" makes such a repetitive point about the importance of dreaming that the viewer should at least be able to easily sum up what Max learns by the end of the film (like, say, "The Wizard of Oz"); instead, all this talk of dreams just becomes a nightmare.

Where did the budget go?

"The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl" is, on the one hand, refreshingly colorful and vivid. During a time when even kid-targeted action movies were slowly inching towards gloomy, dystopian films like 2008's "City of Embers" and franchises like "The Maze Runner" and "The Hunger Games," it stands out as a unique vision. On the other hand, when an adult watches "Sharkboy" they see a film drunk on its own greenscreen power, one that makes you wonder how it could have possibly cost $50 million to produce.

For starters, the money certainly didn't go into the screenplay. At the time of its release, 3D technology was all the rage; but the film is clearly nearly entirely shot on greenscreen, with a setting like the planet Drool filled with low-res backgrounds and choppy effects that look like a computer screensaver. For perspective, a decade prior the original "Toy Story" was produced by Pixar for $20 million. As an adult watching "Sharkboy" in 2021, it's hard not to be distracted by visual effects less sophisticated than we're accustomed to seeing from an Instagram filter.

Ultimately, the 3D technology (at the time, viewed as something a saving grace for the theater industry) just made the movie look even worse in theaters when it came out. Arriving on the coattails of James Cameron's "Avatar" (at the time, the highest-grossing film ever made), 3D was suddenly mandatory for every action film, but while some spent the money to use Cameron's preferred methods, others chose a cheaper route; many were shot like normal films and then "converted," leading to notoriously dark, headache-inducing 3D like 2010's "Clash of the Titans" remake.

Further complicating matters, "Sharkboy" utilized anaglyph 3D, perhaps best described as the "old-fashioned" 3D used in classic B-movies like 1953's "House of Wax" or 1982's "Friday the 13th Part III." According to Roger Ebert the end result removed "the brightness and life of the movie's colors, replacing them with a drab, listless palette, which is about as exciting as looking at a 3-D bowl of oatmeal."

What does it mean that Lava Girl is light?

As a dream within a dream (within a dream?), "The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl" positions itself early on to employ free-associative, dream-like logic. Scene to scene, it doesn't necessarily have to hang together precisely. But this places a huge emphasis on the few elements that it bothers to repeat, seemingly indicating such touchstones are vital to the larger story being told.

One of these is Lavagirl's identity, and several times Max needs to either remember or dream up an answer to who she is. She seems fundamentally afraid, for some reason, that she's an inherently malevolent force, fire or destruction. She wonders this aloud, and is visibly sad when she repeatedly accidentally burns things (including Max's all-important dream journal).

This builds up to a semi-climatic moment. Lavagirl passes out and Sharkboy tosses her into a volcano to revive her, while Max offers a monologue about how she's "something more important" than destruction, she's light. As the music swells, Lavagirl appears to be very happy about this; other than a brief, dazzling flash of light that seems to annoy bad guy Mr. Electric (George Lopez), however, the identity realization doesn't seem to signify much else. Lavagirl eventually "rules over" the volcanos underneath the Earth's surface (you'd think she'd rather stay on Drool, her home planet, but okay), and other than being definitively not evil, it remains unclear what "being light" means for her future.

Were no voice actors available?

Circa 2005, George Lopez was also at the height of his powers. He was in the middle of his run on the highly-rated 2002-2007 sitcom "George Lopez" (becoming one of the few Latinos to ever star in a TV series), he was a well-known celebrity who popped up on shows like "Curb Your Enthusiasm," and a well-respected veteran stand-up comedian. In "Sharkboy," Lopez fully commits to his dual role as Max's teacher Mr. Electridad, as well as one of the chief bad guys on Planet Drool, Mr. Electric.

Both roles are over the top, of course, but in the grand tradition of something like Peter Sellers in "Dr. Strangelove," there was precedence for something special. Lopez mostly pulled it off, issuing bizarre teacher punishments like ordering Max and his bully to be friends, or spouting constant electricity-based puns of the worst order as a floating orb with plugs for hands.

But why did George Lopez have to also voice Max's childhood robot Tobor (who appears twice on Planet Drool to offer Max sage advice)? Following the success of the "Shrek" movies (which had Cameron Diaz earning millions to provide a voice that sounded exactly like ... Cameron Diaz), Hollywood had developed something of an obsession with casting movie stars in voice roles, largely ignoring an entire industry of talented voice professionals who had been providing Mel Blanc-like talents to cartoons and animated movies for decades.

So, rather than finding the proper voice actor to design an endearing, entertaining identity for Tobor from the ground up, instead the audience once again gets George Lopez (later, he appears a fourth time as the guardian of the Ice Princess). At one point, Robert Rodriguez even voices a talking shark himself, further robbing viewers of creativity for mediocre, uninspired stuntcasting.

Taylor Lautner was clearly a future star

Out of everyone in "Sharkboy," it is clear that future "Twilight" heartthrob Taylor Lautner is the actor who possesses "it," that undefinable quality that makes a movie star, well, a movie star.

When production on the film began, Lautner was 12 years old. He already had an extensive martial arts background (Rodriguez asked him to choreograph his own fight scenes), earning a black belt by age 8 and appearing in a 2003 national karate tournament.

Lautner was the first and only actor to audition for Sharkboy — Rodriguez was that convinced he was perfect for the role — and sure enough, his personality is effective glowering menace, as he never stops moving and rages easily, snarling and yelling with full abandon. He has the most standout action scene of the film, using his martial arts skills in an elaborate fight with Mr. Electric's dog-like cord monsters. He's a ball of energy, one that would later be utilized in both half-human, half-animal "Twilight" roles and would-be action flicks like 2011' "Abduction" and 2015's "Tracers."

In "Sharkboy," Lautner takes center stage for the most bizarre and memorable scene of the entire film, an insane, altogether-too-aggressive lullaby that he sings to get Max to fall asleep and dream planet Drool back to its rightful shape. He busts impressive dance moves while sing-yelling absurd lines like "Don't despair, step right up! Glass of water? Here's a cup!" It's a shame that Taylor Lautner couldn't return for the Netflix sequels, as he was the true star of the original "Sharkboy and Lavagirl."

What exactly is an allegory for what?

The whole point, you'd think, of having elements of Max's dreamworld echo elements of Max's real world would be to illuminate his relationships with the people and things that surround him. Sharkboy and Lavagirl, for example, ask Max why he made them a team when they're fundamentally "incompatible," the same word Max's mother used to describe why she and Max's father are not getting along. Such moments could, if properly and somewhat clearly presented, give a film like this greater depth.

But Sharkboy and Lavagirl move past the question as quickly as they bring it up, and Max's parents then appear briefly as cookie-hungry giants on planet Drool who never return; their real-world counterparts move past their squabble without any resolution, seemingly content to remain married, incompatible people.

Then there's Mr. Electricidad, who allows his daughter out of his control, so she can destroy a giant robot that has his own face on it. Objectively, you'd think that this would be a bit disturbing, but he seems to have no problem with it. Such moments don't seem to connect to any greater meaning, other than revolving around a loose, Freudian concept of dreams being inherently meaningful.

Why do Sharkboy and Lavagirl eat Max's cookies?

It might see like a minor detail, but early on in "Sharkboy and Lavagirl," Max wakes up to find the cookies in his kitchen have been consumed. One of these cookies has jagged, shark-like teeth marks in it, while the other is burnt and remains hot to the touch.

His parents, of course, don't believe his repeated insistence that it wasn't him who ate the baked delicacies — and clearly, judging from the evidence, it was Sharkboy and Lavagirl. It's not until the next day that the duo reveal themselves as actually existing, recruiting Max to help them save planet Drool while he's in class.

As cute as the scene might be, it also begs a question: Why bother sneaking into his house the night before they were going to contact him anyway? Are these two Santa Claus? Did they think it would be funny to get him into trouble? Not only has Max seemingly discovered that Sharkboy and Lavagirl are real, but in this scene he also learns that they are decidedly not cool.

There are strange, vague jokes about sexuality

"The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl" has a few off-putting attempts at the sort of wink-wink adult humor other children's movies sometimes tackle with wit and subtlety. But here, they come across as awkward at best, and at worst just plain confusing.

At one point, Sharkboy says he's heard that the Ice Princess is the "most beautiful girl on the planet," causing Lavagirl to get jealous and zap him in the butt with her lava powers. Are they dating? What's the deal there?

Other moments include Linus saying "She's hot!" when Lavagirl burns his desk; later, Mr. Electricidad repeatedly insists that Max stay away from his daughter. In moments like this, it feels like you can see remnants of a screenplay with jokes intended for adults, but ultimately more half-baked than the cookies in Max's kitchen.

In "We Can Be Heroes," the Netflix quasi-sequel to "Sharkboy," it is revealed that Sharkboy and Lavagirl eventually got together and had a kid. So, at some point it seems this vague innuendo eventually became explicit innuendo.

How does Max fall asleep while he's asleep?

After he wraps up his battle with Linus/Minus on Drool, Lavagirl tells Max to blink three times, which will take him home (a la Dorothy knocking her heels together in "The Wizard of Oz"). When he does so, he wakes up back in his classroom, the tornado still raging outside, implying that a large portion of what we've just seen was a dream of some sort.

But during that "dream," Max fell asleep and had another dream inside of it. How is that even possible? "The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl" is a lot like "Inception," but without Leonardo DiCaprio patiently explaining things to Ellen Page for our benefit. There are dreams within dreams, and then dreams intrude on what you thought was reality all along. Like dreams themselves, it's as impossible to follow as it is to explain to anyone else.

How can Sharkboy drown if he has gills?

This is yet another nitpick, but it's the sort of thing that can really nag an adult. Until the very last battle on Drool, it is made abundantly clear that Sharkboy possesses the shark-like abilities of a shark. Raised by sharks, we are told, he grew sharp teeth and gills, and learned the shark way of life.

Yet, in the big fight with Mr. Electricidad, electric eels get the better of Sharkboy in the water, and Sharkboy nearly drowns. You know, because sharks have to watch out, or they could drown.

What about the gills that we saw all up and down his sides, at the beginning of the film? It's an example of a screenplay giving a character a newfound limitation, simply because it is called for at that particular moment to build dramatic tension. It's also frustratingly lazy.

Earlier, when our heroes approach the Ice Princess's tower, we learn all of a sudden that Lavagirl has to fall asleep and sleepwalk across the bridge so it doesn't melt. This is another example of the duo's powers (and limitations) not being properly explained to the viewer, so when an issue arises it just feels like a convenient cop-out. Nearly two decades later, "The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl" continue to hold a special place in the hearts of those who discovered it as kids; based on moments like these and others described above, you'd probably be doing yourself a favor to keep the movie in your memories, not re-visit it on your streamer of choice.