West Side Story Review: Divided We Fall

Steven Spielberg has waited decades to helm a musical. But from the first sequence in the new "West Side Story," it feels like he's a certified genre veteran. Much of that comes from the fact that Spielberg, a filmmaker who has always been so popular that his preternatural gift for deft camera movement and immaculate blocking almost make him underrated, appears to be bursting at the seams to tackle the stage show Robert Wise made an indisputable classic with his 1961 adaptation. There is something infectious in the approach he and his usual band of collaborators, among them cinematographer Janusz Kaminski and editor Michael Kahn, employ in adapting a film that, quite frankly, wasn't exactly begging for a refresh.

For its time, the original "West Side Story" felt startlingly modern. Hell, it still does, even today, so it isn't like Spielberg and company were ever going to outfox Wise in that particular arena. This new version doesn't even update its setting, as it still takes place in 1950s New York City, beyond the metatextual fact that all of the Puerto Rican characters are played by actual Latinx performers — one of the film's only undebatable improvements. But this movie doesn't exist because anyone thought they could or even desired to "beat" the 1961 film.

Spielberg, the biggest living filmmaker on Earth, wanted to make a damn musical, and he happened to choose this one, probably through some mixture of childhood nostalgia and thinking something about how we as a people are more divided than ever, so why not explore those ideas as bluntly as possible through song and dance? It's true that Spielberg has never met a salient point that he couldn't, through his own uniquely sentimental perspective, nail on the head repeatedly to reliable fanfare. But "West Side Story" is still one of the most enchanting and entertaining filmgoing experiences of the year. It boasts an incredible ensemble, some of Spielberg's most visually arresting work in years, and feels like an ornate piece of machinery, with every intricate element firing at all cylinders.

Well, almost every element.

Us vs Them, but make it fashion

The film's initial promotional images were truly alarming, typified, as they were, by a strange and off-putting commitment to beige tones and bland imagery that felt like someone deep-fried Luca Guadagnino's "Suspiria" remake for sport. But we can happily report that the finished film is sumptuous, with Adam Stockhausen's production design smartly echoing the Technicolor flash of the original film, but muting the colors just enough to imply an interpretation of the material that's more Cinema Verite than CinemaScope. That's not to say there's not still extravagant set pieces performing all the classics from the show, but that the spaces between the songs feel more pointed, more acidic.

That shouldn't be much of a surprise with Tony Kushner on script duties. Ever since their collaboration on "Munich," Kushner collaborating with Spielberg allows for the storied playwright to use his way with words to dramatically articulate the darker, thornier sides of the ideas the director wants to explore. The gist of the narrative is the same, focusing on the star-crossed love story between Tony (Ansel Elgort), the former leader of the Jets, an all-white street gang, and Maria (newcomer Rachel Zegler), the younger sister of Bernardo (David Alvarez), the current leader of the Sharks, a Puerto Rican rival gang. It's still a melodramatic "Romeo & Juliet" retread, at least in terms of narrative structure, but Kushner brings the themes to the forefront, with plenty of scenes outright addressing ideas from the original that were only heavily implied.

This provides texture and grit to the supporting players' various subplots. Bernardo no longer feels like a Tybalt-esque hothead, but a man who must be tough and aggressive to protect his people in the hopes he can make it safer for his sister and the newer generation to not have to scrap so hard for what they want. This is especially evident in the way the Jets are framed, with Corey Stoll's Lieutenant Schrank taking frequent breaks from his overt racism against the Sharks to lambast the boys for being gutter trash. By positioning this turf war in front of a backdrop of demolition and future gentrification, there's a larger element of class to the proceedings than the racial/cultural animus on the surface.

Not every modern flourish or further sketched out extrapolation lands as well, though. Anybodys, the "tomboy" wannabe Jet from the original, is more explicitly portrayed as a young trans man, with nonbinary performer Iris Menas in the role. It's an admirable bit of onscreen representation, but the framing of a gender-queer youth needing to ... uh, join an ethno-nationalist street gang to feel more masculine could have fueled an entire Sundance award-winning indie, if left the room to be properly unpacked. Here, it just feels like a strange aside incongruous with the rest of the film's aims.

But it's genuinely hard to have many complaints about a movie that moves this well, that feels so exhilarating to behold. The last couple of times Spielberg was this purely balletic behind the camera, it was shrouded in mo-cap for "Tintin" and "Ready Player One," so the unbridled thrill of seeing him do what he does best with actual human bodies in motion papers over a lot of the more minor gripes a viewer could potentially have with this remake.

There's just one glaring flaw that is more difficult to overlook than most.

The elephant in the room...

If you have been reading other reviews of "West Side Story," a strict consensus has already begun to form. It's a beautiful movie, not quite as strong as the original, and everyone involved deserves heaps upon heaps of praise for their work.

Except Ansel Elgort.

Elgort, of "Divergent" and "Baby Driver" fame, seems conspicuously absent from even the blindest praise the film has received thus far, and it's not only because he is so demonstrably less suited to the picture than the rest of his colleagues.

Last year, Elgort was credibly accused of sexual assault, an accusation he has since denied, but even in the age of "cancel culture" it has not yet begun to affect his career prospects. Unfortunately for everyone else involved with this film, if the viewer is even loosely aware of what he's been accused of, it can't help but color the film itself. There's an entirely separate conversation that can be had about separating the art from the artist and engaging with a work on its own merits, but context matters. The same context that allows Spielberg and Kushner to draw broad parallels from the turf wars in '50s NYC to the political divisiveness in a post-Trump America, a key driving force behind this iteration of "West Side Story," makes it nearly impossible to be swept up in the romance between Tony and Maria.

Despite ostensibly playing teenagers in the film, Elgort is 27, and when Zegler was initially cast for this film, she was 17, the same age as the girl Elgort allegedly groomed and assaulted. Perhaps, on some cruel and antiseptic level, if Elgort's performance itself was more masterful, if he was able to do more onscreen than be tall, vaguely handsome, and white at the same time, his starring role would feel less glaring and offensive. Abusers and pests thrive in Hollywood every day, often hiding behind the impenetrable phalanx of their own talent and their toxically supportive fandoms. But Elgort sticks out like a sore thumb, a lone outlier in a movie full of stellar turns from performers who aren't accused of heinous acts.

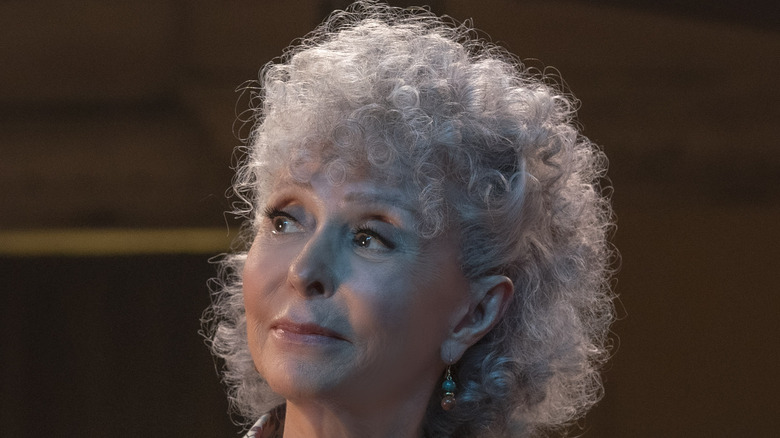

Ariana DeBose's Anita positively shines when it comes time for Spielberg to update the "America" set piece. The originator of that role onscreen, Rita Moreno, steals several scenes as Valentina, a gender-bent mentor figure for Tony. Mike Faist's Riff is a masterclass that brings so much bubbling resentment and tortured self flagellation to the surface.

But Elgort? He's just there. And every time he's onscreen, it's hard not to wish he wasn't.

For a movie so timely, both for the relevance of its themes and for its stature as a fitting tribute to the recently deceased Stephen Sondheim, whose music powers the film, "West Side Story" feels so confounding at times largely due to one regrettable casting decision. For all the genuine physicality he brings to the role, he was a rough choice for the lead even before these allegations became public knowledge. But in their wake, he does little more than tarnish an otherwise lovely picture.