The Ending Of Don't Look Up Explained

Adam McKay's satire "Don't Look Up" is all about the end. A star-studded cast is toplined by Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence as Dr. Randall Mindy and Kate Dibiasky, a professor and PhD candidate in Michigan State's astronomy department that discover a comet that will end all life on Earth in six months and 14 days. What follows is a disastrous series of meetings with American officials, histrionic press appearances, and one campaign of misinformation after the next as "Don't Look Up" answers the question: "What if 'Dr. Strangelove' abandoned all subtlety and restraint and yelled in your face a whole lot?"

A scathing indictment of capitalism, the Trump administration and government bureaucracy, celebrity worship culture, the internet at large, and many more things, "Don't Look Up" is a strange, roiling mix of things that functions primarily as an allegory for our lack of collective action to stop climate change. As it was made during the pandemic, it's impossible not to connect it to the larger, bungled response to Covid-19 as well. DiCaprio and Lawrence rise to the challenge of playing two regular people attempting to grasp with the concept of worldwide destruction while continuing to function in the world, and both have screaming meltdowns at one point that basically read as McKay yelling at the audience himself. It's a rollercoaster of tension and relief, in a certain way, to see the stakes of what we face as a planet made manifest emotionally for once. If everything is as bad as it seems, why are the news anchors always smiling? What are we supposed to do?

In its full-court press in every direction, "Don't Look Up" raises a few hundred times more questions than it proposes any answers or solution, but there's a cogent spirit underlying the broad mechanics of the plot and the absurdist actions of its authority figures. Obviously, thorough spoilers for the entire film follow. Here's the ending of "Don't Look Up" explained, presuming that the end of the world is a concept that we can even get our heads around to begin with.

The catharsis of annihilation

First things first: they don't pull off any "Armageddon"-style heroics in "Don't Look Up." Missions to deflect or destroy the comet are called off or blow up on the launchpad, and a final effort to blow the comet apart and mine the smaller pieces for precious minerals fails at the last minute. The worst of the worst, the power figures and wealthy elite that have utterly failed in the planet's time of need, escape the Earth in a secret ship (more on this later), but the vast majority of humanity goes out with the planet. Our heroes, such as they are, comfort themselves with the fact they at least tried their best to save everyone.

It's bleak, and not terribly surprising given the tone of the entire film beforehand. If "Don't Look Up" intends to serve as a call to action, it basically has to end with the destruction of the planet to outline the stakes that we're all facing. Climate change is real, and we're on the precipice of destruction as a species, and the pandemic has proved relatively conclusively that we're not prepared to work together to end it. Even accepting that there are limits to what we can do as individuals to affect it, the stakes of planetary peril can be clarifying and illuminating in terms of our lives. "Don't Look Up" wants to shake you loose with destruction like the ultimate chair-rattling "4D" theater experience.

Is Don't Look Up a film or a meta-textual essay?

We live in an age when the distinction between media is blurrier than ever. Are the installments of the Marvel Cinematic Universe really "cinema" or just passably entertaining episodes of a 20+ part TV show that's in movie theaters? Similarly, "Don't Look Up" has more or less evenly divided critics on Rotten Tomatoes, because it's somewhere between a film and a two-and-a-half-hour visual essay about our times. Adam McKay has been essentially creating a new medium of storytelling beginning with "The Big Short" and "Vice," and at this point it's kind of silly to walk into "Don't Look Up" expecting a conventionally narrative story from the auteur of this new half-movie, half-editorial type of art.

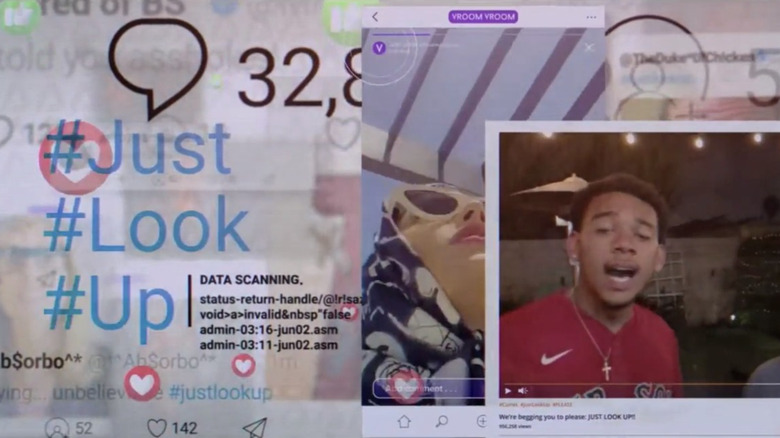

"Don't Look Up" doesn't breach the fourth wall as directly as "The Big Short," which had Margot Robbie talk directly to viewers from a bubble bath, but it's much more relentless in the way that it toggles between tense, small human moments of its leads on the emotional brink, and madcap montages of social media clips going viral along with the talking heads of our 24-hour media cycle egging the public on to madness. Ariana Grande stars as a very Ariana-Grande-esque pop star whose breakup bumps the end of the world to the tail end of the news. In a clear meta-textual message, Meryl Streep plays the fictional President Orlean, named after her character in "Adaptation," a movie that screenwriter Charlie Kaufman wrote himself into and played with the very fabric of cinematic reality. Like Kaufman, McKay drops a hint that he's the one doing the talking, and wants us to have an awareness of all of his characters as paper dolls serving a larger purpose.

We really had it all, didn't we?

After two hours of somewhat cold, over-the-top relentlessness, "Don't Look Up" crafts a poignant ending for the few characters with their hearts in the right place. As the rest of the world either descends into chaos or watches the doomed effort to split the comet up into pieces, the scientists that couldn't convince the world to do the right thing calmly shop for groceries and gather with their loved ones to await the inevitable.

The contrast to the rest of the film is what gives the scene its poignancy. As they buy food and prepare it for each other, as a father puts a reassuring hand on his son's shoulder, as they talk about our miraculous ability to just go to a store and get all the food we need, someone remarks that we sure "had it all" before we wasted it. If there's a moral or message that's of any use from "Don't Look Up," it's to take the literal "Look Up!" message spread by the heroic characters as literally as possible, to look up not just at the sky but to our loved ones' faces and the wonderful world that we still have. Montages of nature and small moments of human intimacy flash as the world ends, in another nod to both "Dr. Strangelove" and "Adaptation" at the same time, imploring us not to miss all of the gratitude we could feel for being alive in this strange, turbulent era to begin with.

Don't Look Up and Make America Great Again

If you're making a film that's explicitly tied to our looming battle with climate change, you have to save the most glaring indictment for the recent administration that removed nearly all mention of "climate change" from government websites. The fictional president, hilariously played by Meryl Streep, only reacts to the news of the comet when it's politically convenient, at first preferring to do nothing and downplay the threat much like the Trump administration downplayed Covid-19 in its earliest stages.

In an explicit tie, when the comet finally appears visibly in the sky, the president and her cronies begin a "Don't Look Up" campaign to convince people not to take the threat it poses seriously. "Don't Look Up" becomes a hashtag, rallying cry, and slogan on hats in a direct reference to "Make America Great Again." It's hard to gauge the success of any political element of the movie, since the various scandals, plural impeachments, and propensity for misinformation of the Trump administration combine with the revved-up modern news cycle so as to exist almost beyond parody, but in a way it grounds the film as the most recognizably pulled-from-reality element.

Greed on a personal scale

While a trio of scientists wait for hours to see the President and give her the news of the comet's discovery, a gruff general played by Paul Guilfoyle comes back from the White House commissary with some snacks and water bottles. "They charge an arm and a leg for this stuff," he says. "Ten apiece ought to do it." Awkwardly, the scientists give him cash to inexplicably discover hours later the snacks and water were free. Of course they were, it's the White House.

Why then, did he do it? Jennifer Lawrence's character is borderline obsessed with speculating on why a Pentagon official would scam them out of 40 bucks for the rest of the story, even as the world nears its total annihilation. It's one of the smallest, funniest touches in the film, and it's never explained as she never gets a chance to corner the general for an answer. With this small touch, Adam McKay skewers the military industrial complex on the way to the apocalypse: with our infrastructure failing, our social services in dire need, and climate disaster looming, it's the defense budget that always goes up and is never questioned.

Peer review versus the billionaire savant

Elon Musk will not save us. Neither will Peter Thiel, Jeff Bezos, or any of the other CEOs of for-profit corporations that can't see the greater good without a profit incentive built in. That's the message behind Peter Isherwell, the CEO of fictional tech giant Bash Digital in the world of "Don't Look Up." He's played by Mark Rylance in a scene-stealing turn as a collection of soft-spoken, halting mannerisms, a sort of cross between Steve Jobs and a children's show mascot.

By the time an individual controls that amount of wealth, McKay points out, they have only the most warped, distant sense of the civic concern. In the movie, Isherwell engineers the abrupt cancellation of a NASA-backed effort to destroy or deflect the comet, and convinces the president to let his company lead a privately funded effort to blow it into smaller pieces, to harvest valuable minerals it contains. With no oversight and no respect for the larger scientific community, the mission fails utterly. McKay positions the scientific method and larger peer review method of reaching consensus as directly opposed to the false idols of tech CEO visionaries. People like Steve Jobs might change the world, but we can't look to them to save it.

Faith during the end times

A surprisingly sweet character that shows up late in the movie, Timothée Chalamet's Yule is given the most compelling moment when he says a simple prayer during the final destruction of the planet. In a film about the literal end times, it's surprising that Yule is the only character that even mentions religion, and not even the Book of Revelation for that matter. Initially presented as part of a pack of nihilistic skaters that seem to have embraced the inevitability of humanity's doom, he soon reveals himself to be the most sensitive, thoughtful character, and a former evangelical Christian that found his "own relationship" with God.

In the end, his prayer brings visible solace to the rational scientists that he's having dinner with. It's an easy to miss, understated part of McKay's message, but it's key that Yule has his own relationship to God. At its worst, religion can divide us, but if we find our own version of it, whether it's God or the scientific method, faith can bring us closer to one another in the worst of times.

A new home for humanity

It's tempting to look to the stars for an answer if the Earth is doomed. A common scenario in science fiction is the idea of colonizing either Mars or some distant planet to save the human race. But the reality of those scenarios could easily result in only sparing the lives of a wealthy, privileged few, as happens in "Don't Look Up" when just a handful of VIPs join Peter Isherwell on his secret escape ship, entering cryo-stasis to sleep for thousands and thousands of years.

The reality of space travel in any form, however, is that it's dangerous and unforgiving: as technology currently stands we have a much better chance of saving the Earth than successfully leaving it behind. To drive this home, "Don't Look Up" has a mid-credits scene when the survivors, mostly white and elderly and leaving their ship naked and looking preposterously frail, are immediately beset by danger on a new planet. The President herself gets eaten by a "brontoroc," which had been cryptically predicted as her cause of death by an algorithm earlier. It's a final, bleak reminder of how even the 1% can't save themselves from the natural order of things, on this planet or the next.