The Untold Truth Of Pan's Labyrinth

In the wake of the billion-dollar success of Disney's Tim Burton-directed version of "Alice in Wonderland" in 2010, Hollywood saw an explosion of darker, more adult versions of fairy tales and fantasy classics. But the definitive take on the concept had already existed for almost half a decade in "Pan's Labyrinth." Instead of a shallow reading of a single, familiar story, writer-director Guillermo Del Toro drew from his lifetime love of the form and its recurring themes to create a new fairy tale that seemed like it had always been around. Instead of overlaying PG-13-friendly sex and violence, he created some of the most horrific images in fantasy history and gazed unblinkingly at the real-world darkness of fascism.

Once upon a time during the Spanish Civil War, there was a girl named Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) who met her wicked stepfather, a Fascist general, and a mysterious Faun who told her she was really a princess of the Underworld who could regain her throne if she passed three tests. The results are a modern classic, in no small part because of Del Toro, a visionary and perfectionist who surrounded himself with other visionaries and perfectionists to bring their dreams to the screen. That means the process behind realizing those images can be as fascinating as the film itself, as these stories show.

Guillermo del Toro turned down his blockbuster dreams to make "Pan's Labyrinth"

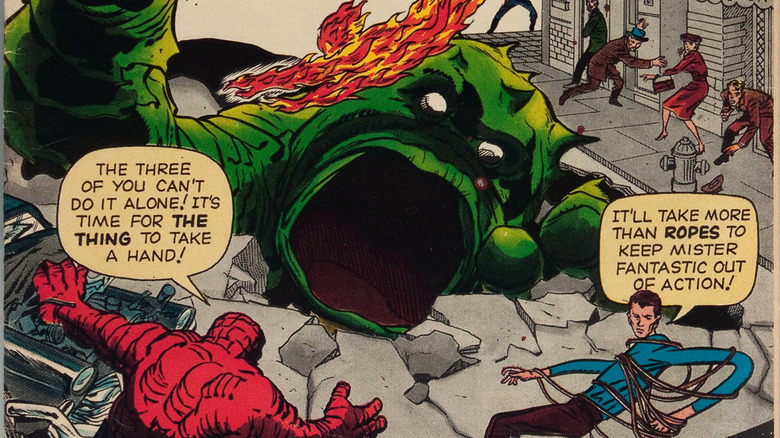

"Pan's Labyrinth" was a major turning point for del Toro. A word-of-mouth hit, six-time Oscar nominee and three-time winner, it earned its director the clout to more or less write his own ticket from then on. But as he began work on "Pan's," the director was on the precipice of a very different type of success. In "Cabinet of Curiosities: My Notebooks, Collections, and Other Obsessions," del Toro recalls the staggering number of big-ticket offers Hollywood was bringing his way on the strength of earlier films like "Hellboy" and "Blade II," including "The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe," "X-Men 3," and "Thor." The one he came closest to saying yes to was another Marvel project, "The Fantastic Four," but even that fell by the wayside.

He didn't make that decision lightly. It took a lot of soul-searching and what might have been a sign from above, or within, for del Toro to say no. Almost as much as his films, the director is famous for his collections of notebooks full of musings and magical ideas. While he was pondering the offer, he lost one in a London cab. "I really cried and cried and cried because these notebooks are for my kids," he wrote. Based on Freud's theory that "nothing is accidental," he searched for his secret reason for losing the book and finally found it: Those notebooks are himself, and he lost the notebook because he was about to lose himself. So he decided to choose the personal project over the Hollywood paycheck, and the result was his masterpiece.

The crew bought two live stick bugs named Cheech and Chong

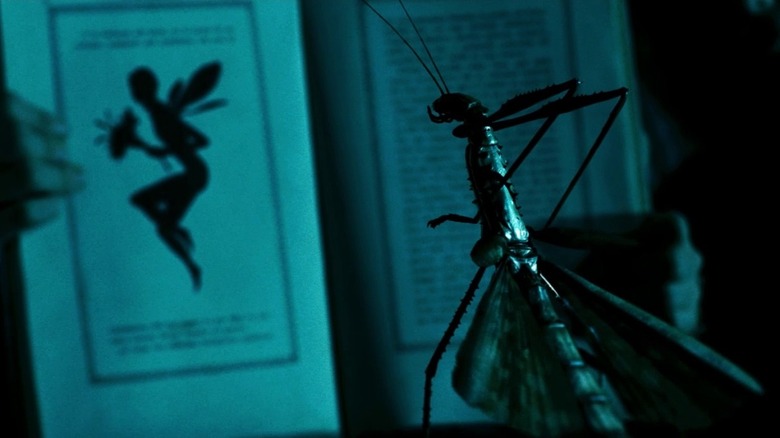

Del Toro has always been more interested in monsters than "normal" people, and "Pan's Labyrinth" is full of some of the most compelling creatures in movie history. Most of them come from familiar folklore, but instead of repeating the images we've seen a million times, del Toro and his team make the age-old fairy-tale characters into something new. That includes the fairies themselves, nude, otherworldly figures with leaflike wings that first appear as giant stick insects.

In the "Enhanced Visual Commentary" for the "Pan's Labyrinth" Blu-ray, visual effects supervisor Everett Burrell describes the crew's commitment to realism in creating these unreal creatures. Del Toro gave the effects team his personal taxidermied specimen for reference, and they later got in touch with a "bug guy" who provided some live samples. Burrell says they "became parents" to two stick bugs, even naming them Cheech and Chong after the legendary stoner comedians of the '70s.

Del Toro imagines Vidal 'disappeared' Ofelia's real father

While fairy tales are synonymous with simplistic, archetypal characters, "Pan's Labyrinth" creates a villain who's more fully realized than the heroes of most movies. As played by Sergi López, Capitan Vidal is a man with a rich interior life. Behind his external cruelty is a relatable desire to excel so he can escape his father's legacy and build one of his own to pass on to his son. But instead of making him sympathetically misunderstood or excusing his actions, all this only makes him more vividly horrible.

This wouldn't be possible if del Toro didn't know even more about his creation than he has time to reveal to his audience, and he shares his theories about what Vidal gets up to offscreen in his commentary. We first meet the Captain after his marriage to Ofelia's mother Carmen, following the death of her biological father. "I wanted to create the suspicion," del Toro says, "of maybe the captain had him killed, maybe the captain had him 'disappeared' to date the mother, you know? It's never revealed, but I like stories with loose ends like that. Contrary to Hollywood screenplay writing, I love to leave threads for the audience to speculate and talk about."

The toad could have had a fight scene if it wasn't so heavy

Ofelia's first task is a classic folkloric dilemma — to save a tree from the toad that's been poisoning it from the roots up. In del Toro's larger-than-life fairy tale world, it's not just any toad but a pony-sized monster of no known species. That turned out to be a problem when it came time to shoot its confrontation with Ofelia. Del Toro explains in his commentary that he had built a much larger, "absolutely gorgeous" set for the inside of the tree, "with a dripping candelabra of amber in the center," and planned an extended action scene between Ofelia and the toad.

But when effects company DDT came back with their life-sized frog animatronic, it was too heavy to fight much of anybody. With the frog just sitting there dwarfed by the cavernous set, it no longer looked huge or intimidating. Del Toro had to think fast — "the scene was one thing on Friday, and it was another thing on Monday" — so he found a solution on a much smaller set that was originally only built for Ofelia to crawl through on the way to the larger chamber. The cramped space made the toad look bigger, and the clumsy animatronics were supplemented with CGI to create the sequence that reached theaters.

The father of magical realism inspired the Book of Crossroads

If one thing makes del Toro stand out from his peers, it's the enormous range of influences he draws from. He takes the obvious ones from popular culture — cartoons, comic books, horror movies — but he's also exceptionally well-read and finds ways to combine nearly everything he learns in ways that obliterate the traditional high art/low art divide.

For instance, in "Cabinet of Curiosities," he reveals the origin of the Book of Crossroads, which starts blank and writes itself based on Ofelia's choices: "The Book of Sand" and "The Garden of Forking Paths," two stories by the Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges that explore the idea of an infinite book. In "Garden," the seemingly inconsistent book is actually a "labyrinth" that shows the results of every possible decision by its characters. Meanwhile, the Book of Sand is a literally infinite text that seems to grow new pages every time the narrator tries to turn back to the beginning or ending.

Considered the father of magical realism, Borges' approach was much like del Toro's. The French author Andre Maurois has said, "Borges has read everything, and especially what no one reads anymore." "Garden" alone combines spy thrillers, WWI historian Liddell Hart, Plato, Newton, Roman chronicles, and Classical Chinese novels. In a way, the whole concept of "Pan's Labyrinth" owes something to Borges, since labyrinths are such an essential image — not just to "Garden" but all his writing — that one of the most popular English translations of his work is called "Labyrinths."

One draft included dead children who eat fairies

As anyone who's seen his notebooks or the list of projects he's been attached to knows, del Toro has 100 ideas for every one that reaches the screen. He developed and abandoned one especially uncanny concept for "Pan's Labyrinth." "Cabinet of Curiosities" reproduces a notebook page with a cryptic reference to Ofelia's second trial in a secret room, where "the dead children who eat fairies appear to her." That idea of dead children apparently stuck with him through the development of "Pan's," since he also jotted down notes for a scene of some that "the well swallowed up."

But they never made the cut, perhaps because they would have been too similar to the ghostly boy from del Toro's previous film about the Spanish Civil War, "The Devil's Backbone." That doesn't mean audiences should give up on seeing the fairy eaters in some form. Del Toro's images have ways of appearing across his projects: The Faun's fairy helpers first appeared as jarred specimens in Hellboy's room, and the Angel of Death in "Hellboy II: The Golden Army" resembles del Toro's sketches for a never-finished adaptation of Christopher Fowler's "Sparky." As for "Pan's," the dead children's role went to a more traditional "ogre" figure, but that wasn't the end of the process.

The Pale Man went through many strange incarnations

If there's one thing everyone remembers from "Pan's Labyrinth," it's the horrible image of the Pale Man. He's only onscreen for a few minutes, but his eyeless face and unearthly screams have haunted viewers for over a decade. So it shouldn't be surprising that he was the result of a lot of trial and error. Del Toro's first idea was "the nerve ghost," a disembodied red nervous system with an electric blue face and hands. After that came a wooden puppet, appearing in some sketches growing out of a tree and in others covered in drawers that could open to reveal fleshy, gooey appendages. The Pale Man became more pale and man-like but still much different from his final form, with del Toro envisioning his eyes not in his hands but floating in his liquid-like, undulating face.

Inspiration finally struck when DDT turned in a bust of the Pale Man and del Toro saw the eerie, manta ray-like face that would take shape if he removed the eyes. The effects artists weren't happy to start over, but it's hard to argue with the results. Even then, the Pale Man wasn't quite finished — "Cabinet" includes a storyboard of an unused effect where a horse-like jawbone emerges from his mouth as he bites off a fairy's head.

The movie's most iconic image came from a sacrilegious source

As "Pan's Labyrinth" goes on, the real and fantasy worlds begin to intersect, and del Toro envisioned the Pale Man in his cathedral-like lair as an image of the true-life horrors of Franco's Spain, and especially the complicity of the Spanish church. He refers to the slits on the Pale Man's palms where he inserts his disembodied eyeballs as "stigmata," in reference to the wounds Jesus received when he was nailed to the cross. In "Cabinet" he makes the connection explicit, recalling a conversation with his wife over whether the Pale Man should attach his hands or his eyes to chase Ofelia: "Why don't we do the stigmata since he's supposed to be the church?"

There's also a more esoteric religious reference that many viewers might miss, but that was branded into del Toro's brain from childhood. In his audio commentary for the original DVD, he traces the image of the eyes on a plate to St. Lucy, a martyr whose eyes the Romans gouged out before executing her. She "was a statue I saw as a kid in a church who had her eyes on a platter and blood pouring out of her eyes." It's easy to imagine young Guillermo keeping that image in his back pocket just in case he ever became a legendary horror filmmaker.

Del Toro envisioned the Pale Man and the Faun as one and the same

The struggle with the Pale Man is one of the darkest scenes in "Pan's Labyrinth." It's certainly the darkest in the fantasy world since it's the only one where we see any of its benevolent inhabitants die: The monster bites the heads off two of the fairies.

But del Toro doesn't necessarily see it that way, and on his audio commentary, he suggests things aren't as bleak as they seem. Explaining why the Faun lets Ofelia move on to the third test after failing the second, he says the Faun always intended for her to continue to the end. Ofelia was never in any real danger from the Pale Man because the Faun is the Pale Man, which is why del Toro cast his go-to monster actor Doug Jones as both characters. It's certainly not the last time the Faun lies about the nature of the tests, as we see in the final scene. And as proof, del Toro points to the ending — even though the Pale Man ate two of the three fairies, there are all three of them, alive and well.

Pan's Labyrinth even scared Stephen King

For all the financial rewards and acclaim that "Pan's Labyrinth" brought del Toro, there was only one review he really cared about. He attended one early screening with his "favorite living writer" Stephen King and his son, "Locke and Key" author Joe Hill.

Del Toro says on the visual commentary, "It remains the single best screening experience of my life to be sitting next to Stephen King and watch him squirm during the Pale Man sequence. That, for me, that's an Oscar. That's absolutely the best thing that ever happened to me in my life." It's hard to argue — who wouldn't take pride in horrifying someone who knows horror better than almost anyone alive?

An experience like that needs to be commemorated, and one notebook page reprinted in "Cabinet" includes a taped-in Indian restaurant receipt from del Toro's post-screening lunch with King where the author wrote "We had a blast!!" with an autograph and a smiley face. Del Toro doodled the Faun underneath King's message, seemingly bowing in gratitude.

Ofelia gets to live out del Toro's childhood dream

When Ofelia explains that she can't give the three tests her full attention because she's worried about her mother's pregnancy, the Faun gives her a magical root to ensure Carmen's health. That root is called a mandrake, and it's a very real folk remedy. Of course, it can't actually squirm and cry like a real baby, but that's not del Toro's invention either — as he admits in "Cabinet," it's a part of folklore going back centuries, inspired by the root's eerily humanlike shape.

None of this information was new to del Toro when he made "Pan's Labyrinth." In fact, he'd known it from almost the beginning. "Cabinet of Curiosities" describes his insatiable childhood reading, especially on anything arcane and occult. "The mandrake root is something I was obsessed with since I was a kid," he says. "I don't know where I read about it, or where I heard about it, but before I was seven years old, I was asking for a mandrake root for Christmas ... Because I wanted to turn it into a living being." No word on whether little Guillermo ever got his wish. But adult Guillermo got to make his own living mandrake, and really, isn't that even better?

The crew had to flee the forest service after blowing up the truck

One disadvantage of choosing "Pan's Labyrinth" over all the big Hollywood productions del Toro turned down was that the money wasn't always there to transfer the script to the screen. Fortunately, the director had already proven himself a master of making small budgets look bigger. In his audio commentary, del Toro remembers the pyrotechnics demanded of the war scenes were especially difficult and made more so by the protective owners of the filming locations. He explains, "I remembered my old days in the theater, and I told [cinematographer Guillermo] Navarro, let's do it with light and steam and mud and water." Other effects included firing air cannons and waving black flags in front of the lights to simulate flickering fire.

One explosion, though, was all real. When the guerillas blow up a Fascist truck, they really blow it up, and it's hard to know how seriously to take del Toro when he says, "As you can imagine, that was the last shot on that location because then we escaped, because the forest guards would chase us." Whether an actual "Looney Tunes"-style chase scene happened or del Toro's just being colorful, we're not going to let the facts get in the way of a good story.