The Untold Truth Of F Is For Family

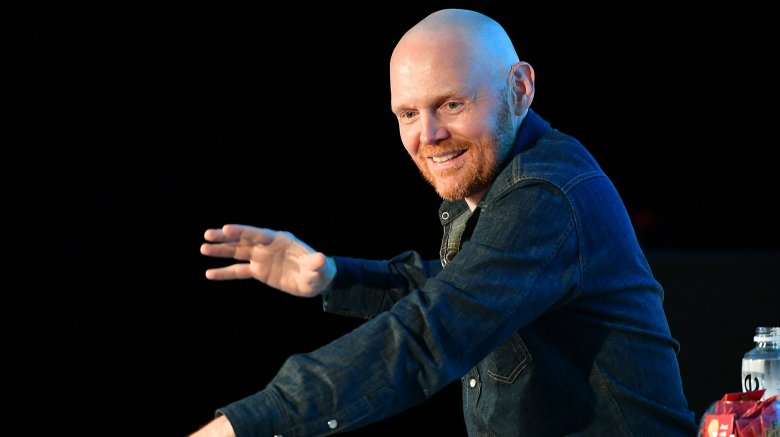

Netflix recently dropped the second season of its original animated series F is for Family, created by comic Bill Burr and Simpsons writer Michael Price, and the response has been somewhat... muted. The show, featuring the tribulations of the blue-collar Murphy family in the '70s, doesn't have quite as high a profile as some of the streaming service's other original offerings. But it should—on top of all that it has going for it on its own, it seems to be part of a larger trend in animated television which is proving that the genre can have much more to offer than just laughs. Here's everything you probably don't know about F is for Family.

It's the best animated show you've never heard of

If the show's title doesn't ring a bell, there may be more than one reason for that. For one thing, the title isn't exactly super-catchy, and doesn't explain much about the show beyond the fact that it's a family sitcom (unless you're the type of viewer whose mind leaps immediately to what else F could stand for). The first season, released in late 2015, consisted of a scant six episodes—not really a strong show of confidence on the part of Netflix—and received next to no marketing push.

Subscribers who decided to check it out despite all this were treated to a series that's well-written, insightful, very funny, and very profane. The sixth episode wrapped up the mini-season's arc nicely while still leaving viewers wondering what might happen next, but despite logging decent reviews, Netflix took longer than usual to address the show's future. The second season of F is for Family was finally announced in April 2016, five months after the first season's premiere. It was released almost exactly a year later—again, absent the teasers and fanfare that typically greet a new season of a Netflix original.

It has a unique production team

The production team behind the series isn't what you might expect. Wild West Productions only had one series credit to its name prior to F is for Family—the short-lived TBS series Sullivan & Son—but Burr found in them a team that could relate to the stories he wanted to tell, mainly the apparent odd couple pairing of Vince Vaughn and Peter Billingsley.

Vaughn founded Wild West in 2005, and called Burr "the funniest, most original voice out there" in announcing their involvement. While Vaughn might seem like an appropriate choice to serve as producer, the same might not necessarily be said for Billingsley, a former child actor who is best known for playing Ralphie in the beloved 1983 classic A Christmas Story.

He's maintained a low-key acting and producing career since that early highlight, perhaps most notably serving as an executive producer in the opening volley of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, 2008's Iron Man. He also appears briefly as an actor: he's the engineer who is screamed at by Obadiah Stane after informing him that he's unable to duplicate Tony Stark's miniature arc reactor.

It's based on Bill Burr's childhood

Burr and Price both grew up in the '70s, and fondly remember what an awesome yet dangerous time it was to be a kid. Burr, who has been compared favorably to Louis C.K. and called the heavyweight champion of rage-fueled humor, is a veteran comic whose four successful Netflix specials made him a good choice to develop an original project for the service. Much of his standup material is mined from his rough childhood, particularly his father, whose angry outbursts he mimics mercilessly in his routines—and upon whom F is for Family's lead character Frank Murphy is based.

Many of the series' situations and gags come directly from specific incidents in Burr's childhood, and Price and the other writers help to weave these recollections into the show's narrative. This lends the ring of truth to its sometimes outlandish interactions and plot developments, which children of the era will recognize as a by-product of slightly more outlandish times.

But it's not just a '70s show

A great deal of the show's humor comes from its setting, from Frank's employer (Mohawk Airlines, with its casually racist TV ads), to jabs at technology of the time (the family's expensive new television is a hulking behemoth with a tiny screen), to the presence of cigarette vending machines. But these all flow naturally from its blue-collar aesthetic, and Burr decided early on to resist the temptation to simply pepper the show with out-of-context '70s gags.

"Our mission statement was: No lava lamps. They [sic] way a lot of shows have depicted the '70s is with a lot of lava lamps and people dressed like John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever," he said. "We didn't want to do that."

Instead, Burr and his writers populated the series with a main cast of characters that are strongly drawn, despite being so recognizable they border on stereotypes. Frank is a bitter underachiever with a crappy middle management job and a volcanic temper. Put-upon housewife Sue has only her side business selling ripoff Tupperware to fill the void. Older son Kevin smokes pot and aspires to prog-rock stardom. Middle child Bill (Burr's surrogate) is a dorky, bowl cut kid perpetually confused by life. And youngest child Maureen is a somewhat creepy enigma. These could all be one-note characters, but sharp writing gives them all surprising depth—and a stellar voice cast doesn't hurt.

Its voice cast is amazing

As Frank, Burr brings every ounce of the vitriol his standup fans are accustomed to while still managing to sell his humanity. But his performance is bolstered by an enviable supporting cast who bring their full commitment to the material—particularly Justin Long, who is more known for roles in films such as Jeepers Creepers and Kevin Smith's recent head-scratcher Tusk. His portrayal of Kevin is alternately on-the-nose and surprisingly nuanced, as the character is slowly revealed to have depths beyond that of your average pot-smoking teen.

Also noteworthy is Sam Rockwell, best known for his role as that guy you know in that movie—seriously, he was in Moon, Frost/Nixon, and Iron Man 2 to name a few—who channels Matthew McConaughey better than McConaughey himself could for his portrayal of laid-back neighbor Vic. Rounding out the cast are American Idol alumni Haley Reinhart as Bill, veteran voice actor Debi Derryberry—best known as the voice of Jimmy Neutron—as Maureen, and Jurassic Park's Laura Dern as Sue.

Burr said of his cast to Boston magazine, "They all came from like an acting perspective where they had to do a number of takes, and you felt with each take it became more and more not them and just this person. It was insane... I basically have a lot of talent around me propping me up. Don't tell anyone."

It has an appropriate animation style

If some viewers experience slight pangs of weird recognition while watching F is for Family, it may be because its animation style has a very specific influence appropriate to its setting. Its simple line-drawing animation was meant to evoke the classic Hanna-Barbera cartoons of the '70s, and it can be a little jarring to see this familiar style used in the service of some highly inappropriate gags.

But the animators also pointed to another strong influence on the show's look: King of the Hill. It's interesting to note that the long-running Fox animated series is perhaps the only other "cartoon" in which the action never once becomes overtly cartoonish—either series could just as easily have been shot live-action. Animators apparently took early note of this similarity, and looked to King of the Hill for cues on how to nail this "animated live-action" aesthetic.

It's an incredibly black comedy

Bill Burr has used the words "complete psychopath" to describe his father during his standup act, and one gets the sense that he's only half-joking. Frank might not be a complete psychopath, but he certainly has more than his fair share of moments of misplaced hostility and blind, almost reflexive aggression. While his family's reactions to his outbursts and impulsive actions are generally played for laughs, the show is not afraid to explore how a lifetime of (continuing) disappointments and failures made Frank who he is, and its season-long arc format gives the writers plenty of space to do just that.

The result is sometimes not pretty, but as volatile as the Murphy family dynamic can be, it's their solid underlying love for each other that pulls the show back when it's edging toward complete bleakness. There aren't many lucky breaks, financially or otherwise, to be had in the Murphy household, and its portrayal of financial struggles and parenting clashes can be brutally honest. But F is for Family also understands that if adulthood is a disappointing and scary place, childhood can be much, much more so.

It pushes the limits of good taste

In the '70s, before the Internet was a twinkle in anyone's eye, children were often exposed to the ugly realities of adult life in a much more face-to-face fashion than today. F is for Family not only understands this, but goes the full distance in exploiting it, in ways that are just as cringe-inducingly uncomfortable as they are shockingly funny.

The third episode of season one, "The Trough," let viewers know what they were in for in this regard. Bill is thrilled when he gets to accompany Frank to a football game, courtesy of Frank's boss and his club seats. But throughout the day, nearly everything that happens—from Frank's racism in refusing to help a stranded motorist to his blatant sucking up to his boss—keeps piling on to Bill's growing disillusionment. This culminates in Frank dismissively sending Bill off to the men's room unattended, an absolutely horrifying spectacle from which Bill comes away with a still-full bladder and a thousand yard stare.

While hilarious, the sequence was an early illustration of the show's intention to not shy away from pointing out how careless adults can damage fragile young psyches, nor to use flagrant gross-out gags to do so. Amazingly, it's not even the worst experience of this type poor Bill has in the first season.

It's also surprisingly poignant

In the same episode, Kevin—who was supposed to go to the game with Frank, but is being punished—takes advantage of his Dad's absence by going off to smoke pot with some friends under a bridge. He brings along a record to roll joints on, which turns out to be an easy listening album his parents used to listen to every night "like they were Mr. and Mrs. Liberace."

He gripes about his "hard-ass" Dad's punishment, but after he and his buddies are sufficiently high, looking at the album takes his memory back to an idealized version of his much more simple, happy childhood (animated in a distinctively '60s style) that brings him to tears and softens his attitude toward Frank.

It's a creative and memorable sequence that not only serves to show us that Kevin is a little more sensitive than we thought, but proves that there's a beating heart—not to mention a flair for the slightly dramatic—underneath the show's crassly funny exterior. That it shares all of these qualities with a couple of other recent animated series has not escaped the notice of some critics, and this may be part of a trend that is just getting started.

It's part of a new breed of animation

It has been pointed out that F is for Family is somewhat of a companion piece to another Netflix series—BoJack Horseman, which somehow manages to blur the lines between absurdist comedy and psychological drama without being a tonal train wreck. While Family forgoes BoJack's absurdist elements in favor of a real-world setting, the series' ability to convincingly play dramatic scenes against comedic ones without suffering from tonal problems is extremely similar.

Even before F is for Family was released, it was noted that BoJack shares this quality with another series that debuted around the same time—Adult Swim's Rick and Morty, which is perhaps even more absurd while bordering on nihilistic at times. These three series in particular seem to have cracked a certain code, though none of them approach it in the exact same way—the ability to give us wacky, surreal, profane, gut-bustingly hilarious animation that also allows us to examine the nature of such weighty concepts as morality, responsibility, and what it means to be a human being.

F is for Family may be the least well-known of the three, but its first two seasons show a ton of potential, and it just might someday be recognized along with Rick and BoJack as part of the first wave of a new genre of animation altogether—one that aims to make us laugh, but also to think and feel.