The Untold Truth Of Disney's Fantasia

Released in 1940 and touted as "the ultimate in sight and sound," Disney's "Fantasia" was (and is) a technical marvel, a bold experiment, and a landmark moment in animation history. As the third feature film from Walt Disney Animation Studios –- following "Snow White and the Seven Dwarves" and "Pinocchio" – "Fantasia" marked a departure from story-driven features to the avant-garde.

At the time, The Saturday Evening Post reported that "Snow White" was snidely called "Disney's folly," as many doubted the film would be as successful as it was. In hindsight, however, that film would be an easy sell compared to what came three years later, when the studio released their most audacious film yet. "Fantasia" combines groundbreaking animation with popular pieces of classical music -– ranging from abstract sequences of light and color to the more familiar narrative sequences we're used to seeing from Disney's history of short films.

The film itself remains a wonder more than 80 years since its release, and it still has the power to astound audiences with its unbridled creativity. Behind the scenes, the stories and secrets of "Fantasia" are as interesting as the film itself, with the studio at the peak of its powers and driven by the passion to create something spectacular. "Fantasia" was ahead of its time, and that is one of the many reasons why it has stuck with audiences for so long. Here, we take a look at the untold truth of the unforgettable "Fantasia."

Leopold Stokowski became involved in the film after a chance meeting with Walt

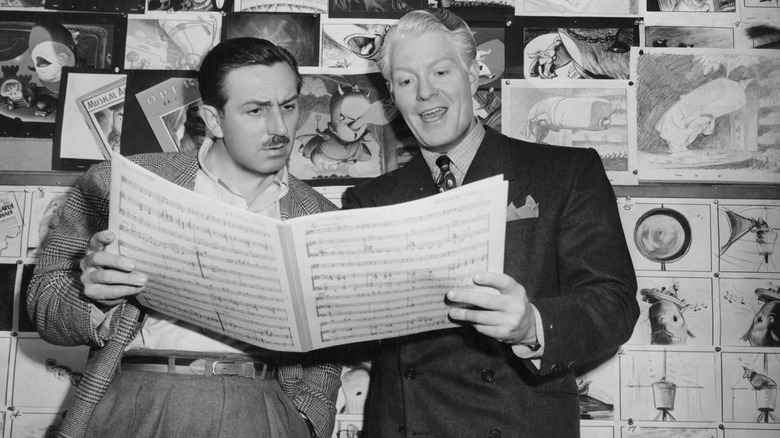

In 1937, Walt Disney began developing plans to set an animated short to composer Paul Dukas' "The Sorcerer's Apprentice," which helped plant the idea for what would become "Fantasia." However, it was due to a chance meeting with conductor Leopold Stokowski that the project evolved into what it is today.

In the 1930s, Stokowski was a superstar, and it was at the Los Angeles restaurant called Chasens – a well-known favorite of the Hollywood elite – that his path crossed with Walt Disney. After sharing his idea for a new "Silly Symphony" using Dukas' music, Walt asked Stokowski if he would be interested in collaborating, and while the conductor agreed, it was under the proviso that the piece would be one that respected the music. With Stokowski on board, the idea evolved into the "Concert Feature" and Walt instructed his animators to "please avoid slapstick gags in the ordinary sense; work instead toward fantasy and business with an imaginative touch," (via The Washington Post).

Initially waiving his fee for conducting "The Sorcerer's Apprentice," once the idea for "Fantasia" snow-balled from a short to a feature, Stokowski's contract was renegotiated. Following that renegotiation, he became heavily involved in the music selection and story development of the film, as well as conducting his Philadelphia Orchestra for all of the sequences — except "The Sorcerer's Apprentice," already recorded using Hollywood musicians. He also appears prominently in the film, albeit in silhouette form.

Salvador Dalí was originally going to be involved in Fantasia

A collaboration between surrealist artist Salvador Dalí and Walt Disney seems unlikely. However, the two creatives were drawn to each other and became great friends. Walt had conceived "Fantasia" as being something that would evolve and change over the years, and one of the ideas floating around after its release involved Dali's work.

According to the book "They Drew As They Pleased: Volume 2" by Didier Ghez, Disney's storyman Bill Walsh suggested "a dream ballet designed by Salvador Dalí" for a possible feature called "A Night at the Ballet." The Saturday Evening Post remembers that after meeting Dalí in 1945, Disney asked him to design a surrealistic short to be part of a musical package film in the vein of "Fantasia."

Work began on "Destino" in 1945 with Dalí collaborating closely with Disney artist John Hench, but it soon became apparent that Dalí and Disney had very different ideas about the story. Dalí envisioned it as "A magical exposition of life in the labyrinth of time," whereas Disney saw it as "A simple love story" (via The Walt Disney Museum). Sadly, less than a year later it was scrapped, although that wasn't to be the last of "Destino."

In 1999, the decision was made to bring the dormant "Destino" back to life. Using the studio's small Parisian team, and French director Dominique Monféry, Dalí and Hench's original shelved storyboards were brought back to life. The finished short was released in 2003 and included Hench's original test animation.

It is the longest Disney animated feature

These days, it isn't uncommon for big-screen blockbusters to push a three-hour runtime. Animation, meanwhile, remains fairly consistent in terms of film length, usually sitting around the 90 to 100-minute mark. Disney's previous feature films, "Snow White" and "Pinocchio," clocked in at 83 and 88 minutes respectively. However, "Fantasia" surpassed them both, sitting at a mammoth 124 minutes.

To this day, it remains the longest Disney Animation Studios film, with the next longest being 2018's "Ralph Breaks the Internet," which lasts 112 minutes. In an amusing coincidence, the film that followed "Fantasia," 1941's "Dumbo" is one of Disney's shortest at a mere 64 minutes. The film's length is something which puts a lot of people off, and it isn't the easiest film to sell, particularly to a child. In his review for The New York Times, Bosley Crowther made an honest assessment of the film's runtime, writing that it "tends to weary the senses," but was still full of praise for the film, going on to say it is the "most original and provocative film in some time."

"Fantasia" is a complete departure from Disney's other films and particularly audacious given the studio's history of bite-sized shorts. This makes it particularly hard to compare to Disney's other narrative feature films as there isn't really anything else like it. Walt's experiments may not have always paid off, but the sheer creativity on display here in "Fantasia" is something that has to be seen to be believed.

A controversial character depiction was removed from Fantasia

There is no shortage of controversial scenes in Disney's back catalog. Variety reports that this prompted them to add stronger content warnings ahead of some of their films on Disney+. Those content warnings flag "negative depictions and/or mistreatment of people or cultures," while also acknowledging, "rather than remove this content, we want to acknowledge its harmful impact, learn from it and spark conversation to create a more inclusive future together."

In the original version of "Fantasia," the segment set to Beethoven's "The Pastoral Symphony" originally featured a character called Sunflower, who is a racist caricature of an African-American girl who shines the shoes of one of the preening white Centaurettes. When the film was re-released theatrically at the end of the 1960s, these scenes were completely removed. However, in the 1991 video release, a different approach was used. John Carnochan, who was responsible for editing the film and preserving it as delicately as possible, re-framed the original shots so they featured close-ups of the Centaurettes instead of the offensive depictions. Acknowledging this troubling aspect of the original film, Carnochan told Entertainment Weekly, "It's sort of appalling to me that these stereotypes were ever put in."

All versions of "Fantasia" are now the re-framed John Carnochan edit, but the controversial scenes can still be found online. While undoubtedly offensive, it is important to acknowledge that these segments exist so that -– like Disney themselves have said -– they can be learned from.

Fantasia was a box office failure

Much like "Pinocchio" -– also released in 1940 -– "Fantasia" was a box office failure despite being largely well-received by critics. The New York Times may have called it "a creation so thoroughly delightful and exciting in its novelty that one's senses are captivated by it," but "Fantasia" arrived not long after the outbreak of World War 2. As a result, the European market was decimated overnight, which had a huge impact on the box office.

Due to the film's complex technical requirements, "Fantasia" was not only an incredibly expensive film to produce but a costly one to screen. Only a few theaters had the patented "Fantasound" speaker system installed to present the film in the way Walt intended. The impact of the war on the overseas market, coupled with the fact not many theaters could show the film properly, harmed the commercial chances of "Fantasia." According to Smithsonian Magazine, it is estimated that it "lost more than the modern equivalent of $15 million and nearly drove the company into bankruptcy."

Ever the shrewd businessman, Disney soon recouped his losses from "Fantasia" by releasing the film repeatedly in the 1940s and 1950s until it turned a profit. It was in the 1960s that the film had a new lease of life, re-branded as a trippy, psychedelic masterpiece that appealed to that generation's conscience. It certainly worked as, according to The Numbers, worldwide box office for "Fantasia" now stands at around $83 million.

The film was intended to be a constantly evolving feature with yearly new segments

The ambition and creativity behind "Fantasia" were unparalleled, but Walt had even bigger ideas for what the film could be, saying that he intended to "make a new version of Fantasia every year" (via Houston Symphony). In May 1940, Walt, Leopold Stokowski, and the Disney artists met to discuss future "Fantasia" projects, throwing in ideas such as Gershwin's "Rhapsody in Blue" and Sergei Prokofiev's "Peter And The Wolf," according to "They Drew As They Pleased: Volume 2." However, by early 1941 it was decided that this dream was too ambitious, and the film's disappointing box office performance meant the plans for an encore were scrapped.

This wasn't to be the end of Disney's musical era, as the impact of war forced them into producing "package films" –- collections of shorts put together to make a feature film. Many of the proposed ideas for a future "Fantasia," along with some of the scrapped ideas from the original, made it into these films, with the aforementioned "Peter and the Wolf" appearing in 1946's "Make Mine Music." The same film also included a sequence called "Blue Bayou" with animation that was initially intended to be used in "Fantasia," set to the Claude Debussy piece, "Clair de Lune." It wasn't until 1999's "Fantasia 2000," however that the previously mentioned "Rhapsody in Blue" made an appearance, and in a way, Walt's dream was realized eventually.

Bela Lugosi provided the initial live-action reference for Chernabog

Bela Lugosi was a Hollywood legend perhaps best known for his appearance as the titular bloodsucker in 1931's "Dracula." So when it came to finding the perfect person to provide the live-action reference for Chernabog, the demonic villain of "Fantasia," Lugosi seemed like the most natural choice.

Disney animators frequently used live-action reference models to inspire their drawings, and there is some incredible behind-the-scenes footage of this from their archives. While their physical likenesses may not necessarily have made it into the film, they played a crucial part in ensuring the animators and artists could accurately re-create real expressions and movements in their drawings.

According to D23, It was in November 1939 that Bela Lugosi spent a day at the Disney Studios "posing for animators and being filmed as live-action reference" for Chernabog in the terrifying "Night on Bald Mountain" sequence in "Fantasia." While Lugosi may seem like he would be the perfect choice for Chernabog, animator Bill Tytla was not satisfied with the footage featuring Lugosi. Instead, the sequence's director, Wilfred Jackson, stepped in as the reference model. It was Jackson's reference photographs, along with the concept art by Kay Nielsen, that ultimately provided Bill Tytla with what he needed to create this iconic villain.

The first film to use stereophonic sound

In the early days of Disney, the company was constantly innovating by creating new technology and equipment to elevate their output from simple cartoons to works of art. Following their invention of the multiplane camera for "Pinocchio," the studio turned its attention to sound and how they could best re-create the immersive experience of listening to an orchestra for theater audiences watching "Fantasia."

Nowadays, surround sound is commonplace, but back then it was completely new, and Walt Disney Studios pioneered this breakthrough. Speaking about his vision for the sound design for"Fantasia," Walt said, "We know ... that music emerging from one speaker behind the screen sounds thin, tinkly, and strainy. We wanted to reproduce such beautiful masterpieces ... so that audiences would feel as though they were standing at the podium with Stokowski" (via The Take).

Disney engineer Bill Garity and the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) were tasked with making Walt's vision a reality, making a multi-channel optical sound system that they appropriately named "Fantasound." Stereophonic sound wasn't available in most American cinemas until 1954, as this piece in Medium explains, which "places the Walt Disney Studios about 20 years ahead of time." The drawback of this enormous leap forward in technology was that most theaters were ill-equipped to screen "Fantasia," with only a handful of theaters having the correct configuration of speakers required –- something that directly impacted the box office numbers for "Fantasia."

Walt wanted Fantasia to be a 4D experience

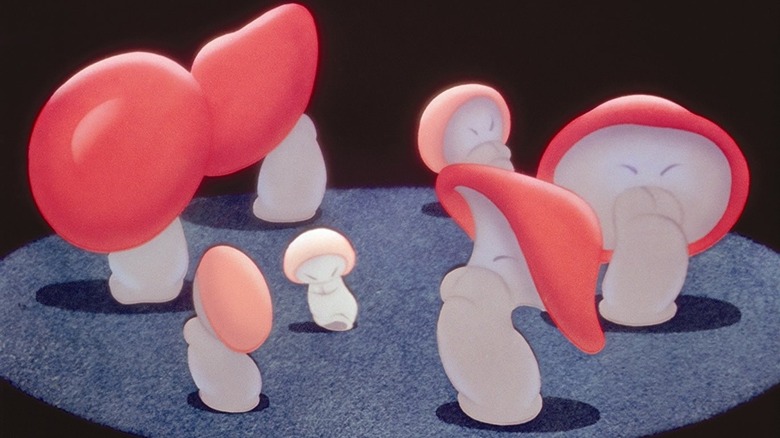

The finished "Fantasia" remains a bold and experimental film from Disney. However, there were plenty of innovative ideas and suggestions that had to be scrapped during the film's production. "Fantasia" saw the studio innovating on all levels, from the abstract animation style seen in the "Toccata and Fugue" sequence to the cutting-edge stereophonic "Fantasound" invented to create a rich soundscape for the film.

Disney intended the film to be one that would "stimulate the audience's senses," as described in "They Drew As They Pleased: Volume 2" by Didier Ghez, going beyond just the sight and sound aspects that traditional movies presented. In Ghez's book, it is mentioned how Walt had considered the use of scents, saying, "For 'The Nutcracker Suite,' he contemplated using atmospheric fans to waft perfume into the theater. Likewise, for "The Sorcerer's Apprentice," "he considered the peppy aroma of gunpowder." The book goes on to say that Disney "even envisioned a panoptic projector that would project all around the cinema."

Many years before they became commonplace, Walt also toyed with the idea of having a sequence of the film in 3D. However, due to the technology limitations, this would've only been possible to do if the segment was in black and white. Unfortunately, the budget for "Fantasia" could never match Walt's ambition and imagination, and many of these ideas had to be shelved.

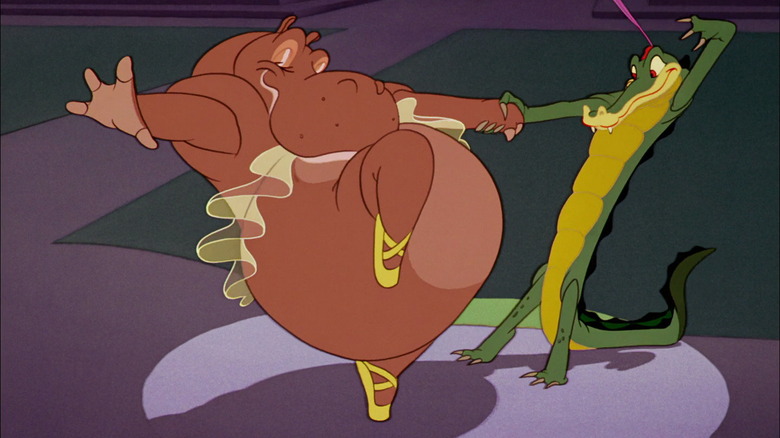

Ballet dancers provided live-action references for Dance of the Hours

Disney animators have always been known for making the impossible seem possible, and in "Fantasia" they brought audiences the delightful sight of graceful ballet dancing animals. This largely comedic sequence, directed by Norman Ferguson and Thornton Hee, features dancing ostriches, hippos, and alligators. However, even for this implausible scenario, Disney was striving for the most realistic animation references that they could find.

Animator John Hench was assigned to work on the sequence set to the music by Amilcare Ponchielli, although he was initially resistant as he apparently knew nothing about ballet. Unphased by this, Walt arranged for him to sit backstage for a week watching the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and study the movements of the performers. In an informal discussion celebrating the 50th anniversary of "Fantasia," Hench said, "I went back there and squatted around and made hundreds of drawings, and came to know the dancers and several ballets quite well. And I changed my mind about ballet."

Several of the companies dancers, including Irina Baronova and Tatiana Riabouchinska, provided the live-action reference models for the ostrich Madmoiselle Upanova and Hyacinth Hippo. Riabouchinska's husband, David Lichine, danced with her, providing the reference for the character of Ben Ali Gator. This wouldn't be the last time the pair modeled for Disney, as "Make Mine Music" features the dancing duo in rotoscoped animation for the segment "Two Silhouettes."

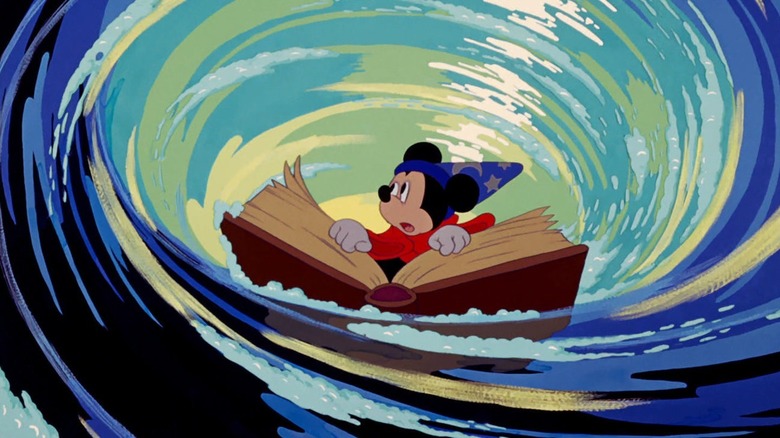

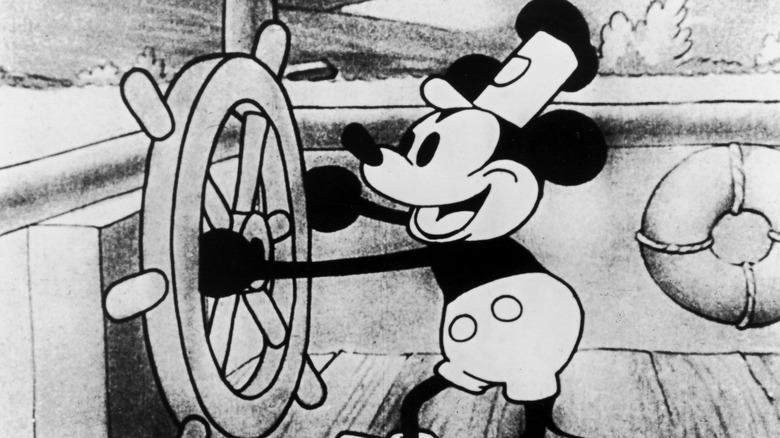

The way Mickey was drawn for the film changed the way he was drawn going forward

In many ways, it is thanks to Mickey that "Fantasia" even exists. Walt had originally intended to release just "The Sorcerer's Apprentice" as a new short in the "Silly Symphonies" series, this time with the prestige boost of a classical score, hoping to take it from the silly to the sublime.

However, it soon became clear that the project was a little bigger than Walt had envisioned, and plans were made to expand the short to a number of animated sequences set to music, making up the "Concert Feature," later re-branded as "Fantasia." The rest was history, and Mickey's appearance in the film not only became one of the stand-out moments but also proved to be surprisingly influential on the way Mickey was drawn going forward.

Mickey's appearance has changed quite dramatically over the years, with his trademark shoes and gloves being added in his early short film appearances in 1928 to 1929 and the red shorts following in 1935 with his first color short film, "The Band Concert." Mickey's eyes also changed during this period, ranging from black ovals to the "pie-cut eyes" before the re-design for "The Sorcerer's Apprentice" that gave Mickey a more realistic look, adding the pupils. It was this design that persisted in the years that followed and is the version of Mickey that most will recognize today.

It has an under-appreciated sequel, Fantasia 2000

While Walt's original intention may have been to constantly change and evolve "Fantasia," it wasn't until 1999 that this vision was partially realized, but with the underrated sequel "Fantasia 2000." If the slightly weighty runtime of "Fantasia" is daunting, its sequel offers a slightly more palatable runtime of just 75 minutes while still retaining that magical quality that made the original so ground-breaking.

Shortly after Michael Eisner became Disney's CEO in 1984, Walt's nephew (and Disney Vice-Chairman), Roy E. Disney suggested a "Fantasia" sequel. Following the success of the home video release of the 1940 original in the 1990s, a sequel was green-lit.

In this interview with Roger Ebert, Roy explained the sequel was originally going to include a lot more of the original film's segments with a few new ones added. However, it was later decided to only keep "The Sorcerer's Apprentice," with Roy explaining, "partly as an homage to the original and partly just because it's still as much fun as when it was new."

Other sequences in the film include the abstract "Symphony No. 5," the "Dance of the Hours" inspired "Carnival of the Animals," and "Rhapsody in Blue," one of Walt's original ideas for the "future Fantasias." Interspersed with a plethora of celebrity guest introductions, including Steve Martin and Bette Midler, "Fantasia 2000" was generally praised by critics and serves as a great reminder of the original's power to enthrall for generations to come.