Things In Drop Dead Fred Only Adults Notice

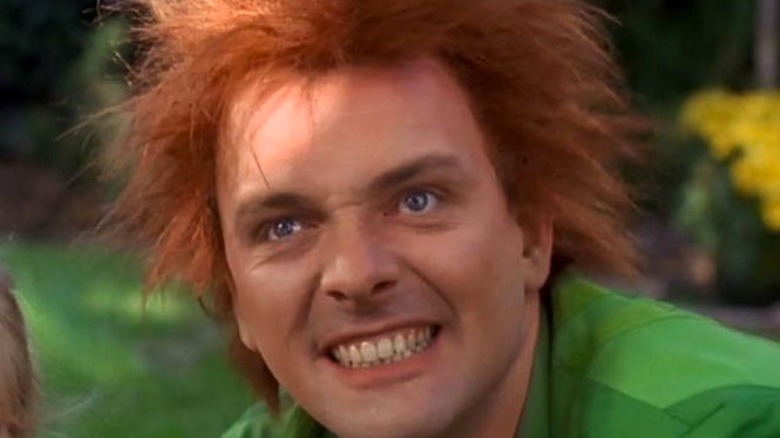

The 1991 film "Drop Dead Fred" is a madcap and oddly dark "family comedy" that left a deep, lasting impression on people who saw it on the cusp of adulthood. Clearly greenlit in the interest of capitalizing on Tim Burton's movies about manic goofballs like "Pee Wee's Big Adventure" and "Beetlejuice," it was originally pitched by the studio to Burton to direct and to Robin Williams to star in the title role (via Little White Lies). Because they declined, Dutch filmmaker Ate De Jong signed on for his Hollywood debut, and fireball British comedian Rik Mayall was cast alongside Phoebe Cates, near the end of her brief career.

Despite this star power, "Drop Dead Fred" was met with mild confusion from audiences and outright repulsion from critics. Gene Siskel called it "easily one of the worst movies I've ever seen" and gave it a rare zero stars (via Chicago Tribune). But the film has slowly earned a legacy for its bizarre tone, madcap energy, and surprising deep dive into issues of trauma and abuse for a film marketed at children. Is it a lesser-known cult classic, or just a bad film? These are the things you notice about "Drop Dead Fred" when you watch it as an adult.

This isn't a comedy, it's a horror movie

When you watch "Drop Dead Fred" as an adult, you keep asking one question: "Is Fred a force for good?" The movie presumes you'll naturally just agree that the impish, imaginary Fred is a positive force in main character Lizzie Cronin's life. At the beginning, she loses her marriage, purse, car, and job in a single day, and her emotionally abusive and stern mother forces her to move back home. Fred returns for the first time since her childhood — seemingly to help her stand up for herself like he did when she was a kid.

But Fred's methods, kindly put, leave more than a bit to be desired. He causes nothing but chaos for both young and adult Lizzie. He gets her father arrested and drives her parents to get divorced (this is blamed primarily on Lizzie's mother's aggressive punishments, but Fred didn't help matters). And he causes a ridiculous amount of property damage, which adult Lizzie is blamed for. She nearly loses all personal autonomy.

Lizzie's husband Charles and mother Polly are uniformly terrible people, which makes Fred's chaotic influence seem better for Lizzie by default, but the experience of watching "Drop Dead Fred" is one of deep anxiety approaching horror. Lizzie is caught between cartoonishly evil human beings and a malevolent green-suited demon. If you don't buy into the idea that Drop Dead Fred has good intentions by default, the laughs are mostly gasps of discomfort.

How did Fred help Lizzie with her mother's abuse?

Fred's primary value, we are more than once told in dialogue, is helping Lizzie deal with her tyrannical mother's constant judgement and harsh discipline. And while it's clearly important for Lizzie to retain her independence and childish free spirit, all of the examples we see of Fred's "help" result in wholesale damage to Lizzie's home that her mother naturally blames on her daughter. This continues the endless cycle of punishment and rebellion. Despite Polly Cronin's (Marsha Mason) penchant for saying explicitly cruel things to Lizzie, it's actually kind of a relief when she locks Fred away in the Jack in the Box, not to be seen again for 16 years.

For example, what part of childhood innocence and identity is served by playing "burglar" and breaking the windows of the house? Especially when it scares Lizzie's parents so much that they call the police. Fred might have been a ballast to hold onto during a difficult childhood, but we see him cause chaos in Lizzie's adult relationships that have nothing to do with her mother. In short, it's possible Fred's the real villain of this movie.

Lizzie doesn't even see her purse get stolen

As the film opens, Lizzie Cronin is having the worst day imaginable. She's desperately trying to salvage her relationship with her husband Charles over the phone after she catches him having an affair. Outside the phone booth, we see a man break her passenger-seat window to steal her purse. The camera makes a point to linger on the purse in the seat, and follow the man's approach as he walks up to the car. We brace ourselves for poor Lizzie's reaction.

But mere seconds later, another guy walks up and steals the entire car. As far as Lizzie knows, her car and purse got stolen together — but the audience knows the truth. Is this is all so we know that Lizzie is having even more rotten luck than she thinks she is? It's a strange sequence that could be read as a subtle gag ... if the rest of the film were even interested in subtlety.

Does Drop Dead Fred exist?

There doesn't appear to be much consistent internal logic in "Drop Dead Fred" about imaginary friends actually function. In short, does Fred exist? He certainly appears to be affecting physical reality, but he doesn't do anything that couldn't be explained by a "Fight Club"-esque situation in which Lizzie is doing these things herself in a dissociative state. That said, there's a flashback where "Fred" throws what appears to be four entire gallons of bright yellow paint at Mickey's grandmother, which is hard to imagine young Lizzie being capable of physically.

In the end, two things point to Fred being an actual, supernatural presence of some kind. First, he finally helps Lizzie free herself from Charles by hearing him over the wall talking to Annabella, when Lizzie is too far away to hear herself. Second, after she says a final goodbye to Fred, he appears exactly the same way to Natalie, Mickey's young daughter. But there's no finality to the question of how real Fred is, which can be irritating. When Lizzie is making absurd gestures with her arms during a lunch with Mickey, are we laughing because a mentally ill woman is flailing her arms strangely, or because a chaotic supernatural presence is tormenting her?

Carrie Fisher plays the coolest woman that's ever existed

Already having played one of the greatest "supportive best friend" roles in the classic rom-com "When Harry Met Sally," Carrie Fisher takes her few scenes as Lizzie's impossibly patient and understanding friend Janice in "Drop Dead Fred" and steals every single one of them. Janice is a high-powered business woman of some sort that lives on a two-story riverboat, is open about having casual sex with her co-worker Murray, and generally storms about and barks orders at people as the most confident, badass woman who ever existed.

Janice is also the only character that accepts Lizzie's word that Drop Dead Fred exists, no questions asked. She is so supportive of her friend that she attempts to strangle the invisible man for sinking her houseboat. She stomps on the floor in front of all of her co-workers, presuming Fred is there, and when someone (quite reasonably) asks what she's doing she yells, "I'm running for Congress! What does it look like I'm doing?!" — as if it were the dumbest question she's ever heard. By far the most triumphant moment of the entire film is when Janice reveals the insurance check for her boat was way more money than she expected and she bellows, "Thank you Drop Dead Fred!" to the heavens. Turns out that her policy had imaginary friend protection after all.

Why does Fred have such regressive views?

In a film of vile, spiteful characters, one character who is actually bright and loyal is Lizzie's childhood friend Mickey Bunce (Ron Eldard). He's the only one who consistently finds Lizzie's Fred-related chaos to be delightful. He patiently helps her sort through her feelings about Charles, and even looks past the commotion she makes at a restaurant as a charming eccentricity.

So why, if Drop Dead Fred is Lizzie's protector, is he so judgmental of Mickey for being open about his feelings? Multiple times, Fred assails Mickey's masculinity: "Look at him, still talking about love! I always said you should be a girl." The knee-jerk reaction of emotions and love being girlish are one of the most dated parts of the movie. Does Fred have Lizzie's best interests at heart, or is he a Don Rickles-esque roast comic, snidely putting down everything he sees?

The imaginary friend community deserves its own movie

Thousands of metaphysical questions are raised when adult Lizzie is taken to a child psychiatrist who specializes in "imaginary friend syndrome." After it's revealed that all the children in the lobby have imaginary friends of their own, Fred greets them all as old friends, implying there's some sort of imaginary friend community. Suddenly, Rik Mayall is euphorically joined by four other brightly dressed actors in fake-vomiting, yelling at the top of their lungs, and hitting one another in classic "Three Stooges" fashion. It's the only scene in all of "Drop Dead Fred" that is definitely too short.

How do imaginary friends get "assigned" to children? Where do they exist when they're not currently with a child? Even though it's implied that Fred was physically locked in the Jack in the Box toy for 16 years, he tells Lizzie he is now "stuck here and can't get home again" until she's happy. So where's home? This is like if "Beetlejuice" cut all of the scenes in which it explored the world of the dead. Why tease the existence of a larger imaginary friend network and then not explore it at all?

What's up with Lizzie and Annabella?

One of the weirdest parts of "Drop Dead Fred" is its handling of adult relationships. Lizzie has virtually no chemistry with Charles, her much older cheating husband. And she has only tentative sparks with childhood friend Mickey, played by the age-appropriate Ron Eldard. But other than some oddly raunchy jokes, the filmmakers decided not to play up any sexual chemistry in the interest of keeping the childhood energy of the premise afloat.

What, then, are we to make of the obvious sparks flying when Lizzie unknowingly bumps into Annabella, who she soon realizes is Charles' mistress? Before this comes up, there's an unmistakable charge in the air as she and Annabella trade compliments on each other's dresses. Annabella even seems somewhat flustered during her delivery of "I like yours, it's very ... purple," before Charles arrives and kills the buzz. It might just be reading too much into the performance of an uncredited Bridget Fonda as Annabella, but you half-expect her to hop into Lizzie's car when she sorts her life out at the conclusion of the story.

Lizzie has no agency for the entire film

Ultimately, what makes Fred's antics so hard to sit through is Lizzie's complete lack of agency or self-respect. The reasons for this, tracing all the way to her childhood of constant mental abuse from her mother, might be reasonable and consistent — but that doesn't make her actions as an adult any easier to watch. All of the actions she actually takes on her own are just to try and get Charles back, who from the very start is clearly a boorish, selfish idiot not worthy of her time. It might be Fred who sinks it, but it's Lizzie who decides to impulsively take off in Janice's houseboat, all because she thought she saw Charles passing by. Who cares?

Even the big, cathartic dream sequence that serves as the film's climax is spurred by Fred finding out for her that Charles is still seeing Annabella. If he hadn't eavesdropped, Lizzie would probably still be married. And while the dream sequence is the most inventive, visually striking part of the movie, it doesn't carry the emotional weight that it should: It's not a culmination of Lizzie's struggle to reclaim her independence, it's literally the first time she's done anything at all to claim it.

Does Fred represent mental illness?

Central to the strange tonal experience of "Drop Dead Fred" is the question of whether he's a manifestation of a mental illness. The movie seems to presume that he's a good thing for Lizzie, as positioned against her mother and husband, but she's also explicitly diagnosed with "Imaginary Friend Syndrome" and given pills that cause Fred to go away. And while harmless childhood imaginary friends are common and easy to distinguish from mental illness, Fred causes Lizzie to behave oddly well into adulthood — and to the severe detriment of her personal life for most of the film.

By refusing to answer the riddle at the center of Fred's existence, "Drop Dead Fred" just adds to the confusion for its entire runtime. Are we rooting for a young woman to continue to suffer mental distress, or to accept the chaotic help of a zany guardian angel?

This might be the most adult PG-13 movies that exists

Multiple points during this movie make you wonder how the studio decided to market it to children. The screenplay has the maximum amount of profanity that's allowable under the PG-13 rating. Fred looks up women's skirts more than once — the second time affecting the bulging eyes and steam-whistle ears of a cartoon wolf. Janice complains loudly and proudly that Lizzie ruined her one night a month to have sex, and boasts of her lover's stamina. These aren't wink-wink double entendre feints at sexuality you find in a lot of "family friendly" movies — they're outright adult things to say.

The result is yet another way the film veers wildly in tone. Is this a children's fantasy where Fred smashes his head in the refrigerator and looks like Flat Stanley? Or is it an intense adult drama where the sound editors make sure to include the noise of Lizzie unzipping Charles' fly? Somehow, it's both at once.

Does Mickey's daughter have the same problems as Lizzie?

After Lizzie's big, cathartic dream sequence gives her the confidence — out of nowhere — to leave Charles, remove herself from her mother's life, and say goodbye to Fred, she promises to see Mickey again and everything seems to be happy. But Mickey's young daughter Natalie has terrorized her nanny into quitting, and Natalie blames it all on none other than Drop Dead Fred. Seemingly, he's moved on to a new child now that he's helped Lizzie self-actualize.

But watching "Drop Dead Fred" with new eyes, is this ending as happy as it appears to be? Even the most sympathetic and positive reading of the film is that Drop Dead Fred helped Lizzie deal with years of emotional abuse and repressed trauma. Is Natalie going through the same thing? In any event, stringing up her nanny from a tree is absurdly violent behavior for a small child, and the prospect of Fred moving on to a new host of sorts is a frightening one when you consider what he's capable of.