Movies Like Don't Look Up If You Like Satire

The punchline of just about every joke in Adam McKay's recent slate of films has been aimed at corporate greed — and "Don't Look Up" is no different. In the star-studded feature, astronomers Randall Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence) are the unhappy discoverers of a "planet-destroying" comet careening towards Earth.

Even as the end of the world looms large, capitalizing on the comet takes precedence over all else: Corporate media milk the impending disaster for ratings; corporations and the billionaires that run them seek to mine the comet for valuable minerals; meanwhile, politicians, including U.S. President Orlean (Meryl Streep), use the threat to line their campaign coffers.

Satires like "Don't Look Up" are charged with walking the fine line between grim reality and absurd fantasy. Veer too much in either direction and the film becomes a drama or a comedy. The best satires successfully provide much-needed comic relief even as they tackle the most uninviting yet pressing issues of their times — be they corporate greed, corrupt politicians, the dysfunctional media ecosystem, or war. If "Don't Look Up" whets your appetite for more satire, satisfy your craving with some of the following greats.

Network

If you enjoyed the way "Don't Look Up" extrapolates a ratings-hungry media to its comedic extreme, you'll enjoy one of its main inspirations on the subject matter, "Network." In this 1976 film, Howard Beale (Peter Finch) has reached the tail end of his decades-long career as a newscaster — as his dipping ratings make apparent. He's not happy about it, though, and on his last day as host, he says as much to his viewers in a lengthy diatribe about the regressive state of U.S. television and life in general.

Fortunately for Beale, the American public laps up his rants, and network producers bank on his rising cult of personality to draw in even more viewers and higher ratings. Beale continues in the network's employ, but the public giveth and the public taketh away, so he remains on unsteady ground. Like "Don't Look Up," "Network" shows the pitfalls of a media culture that runs toward sensational but ultimately superficial headlines and away from serious, honest discussions.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

With "Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb," Stanley Kubrick created a genre-defining movie and helped inspire many more, "Don't Look Up" chief among them. Incidentally, both films were released just as the events they satirized reached a crescendo: "Dr. Strangelove" premiered in the midst of the Cold War and "Don't Look Up" in the dire stages of a climate reckoning.

The common thread running between "Don't Look Up" and "Dr. Strangelove" can be distilled into a single paradoxical line: In times of catastrophe, the most powerful institutions are powerless to do what matters.

Paradoxes are baked into the premise of "Dr. Strangelove." In the throes of the nuclear arms race, superpowers count on the world-ending threat of nuclear warfare to deter each other from using nuclear weapons, thus maintaining a kind of tenuous peace. But in a situation as delicate as this, nuclear war is only one trigger-happy general away, and General Ripper (Sterling Hayden) is only too happy to take the bait. When the world learns that Ripper's actions will trigger a Russian doomsday machine and likely end humanity, the ensuing fallout sends everyone scrambling — much like they do when the selfish, impulsive actions of individuals allow the apocalypse to arrive in "Don't Look Up."

In the Loop

After watching the power-hungry politicians in "Don't Look Up" lie, deceive, and sell their loyalty to the highest bidder, you might imagine it difficult to find a more morally-depraved set of characters. "In the Loop" will challenge that notion.

"In the Loop" is a theatrical spin-off of the popular sitcom "The Thick of It," which is perhaps best known for having spawned the American political satire series "Veep." In this Armando Iannucci-directed film, war is on everyone's mind, but few are of the mind to ask why. As the U.S. and U.K. teeter dangerously close to starting an Iraq-esque war, British Minister Simon Foster (Tom Hollander) finds himself swept up in the furor and shipped across the pond as part of a U.K. delegation.

During talks, politicians from both sides of the Atlantic scheme, manipulate, and double-cross each other to further their agenda, all while lobbing hilariously foul-mouthed insults at one other. Neither the hawks nor the doves are particularly adept at negotiating or reasoning, and it shows. "In the Loop" exposes how the highest echelons of society are often most prone to great ineptitude — something fans of "Don't Look Up" will find disconcertingly familiar.

Ace in the Hole

In "Don't Look Up," even the apocalypse is just fodder for higher ratings and more likes. Chuck Tatum (Kirk Douglas), our tenacious journalist protagonist in "Ace in the Hole," milks a similarly disturbing incident, but one with a much lower body count than the end of the world.

Tatum's professional ambition is superseded only by his drinking habit, which leads to him losing several jobs and eventually settling for a stint at a local paper in Albuquerque. Tatum soon catches his big break when an unsuspecting local, Leo (Richard Benedict), gets pinned down under a fallen cave-dwelling. In his quest for fame and fortune, Tatum begins to create a media circus around Leo (literally, since he stops at nothing short of erecting a carnival for curious tourists).

Through Tatum's sensationalist coverage and the large public appetite for it, "Ace in the Hole" showed us virality long before "going viral" became common parlance. That a movie from 1951 can bear such a striking similarity to recent times is perhaps the clearest sign of how enduring its subject matter is.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

God Bless America

"God Bless America" is an apocalyptic comedy of a different kind. At the outset of the movie, our protagonist Frank Murdoch (Joel Murray) has a similar epiphany to Dr. Mindy's: The world is ending. But the "end" in "God Bless America" is more of a cultural collapse of civilization, brought on by unfettered commercialization. Driven by a rabid sense of nihilism, Frank takes it upon himself to rectify the situation. He finds an unlikely accomplice in a rebellious teenager and, together, they set out to murder the chief culprits of this cultural collapse — that is, reality TV celebrities, unruly teenagers, and zealots. And so the movie puts forth a weighty question: "What if one man's reaction to rabid consumerism was of equally large and absurd proportions to the cultural ills themselves?"

"God Bless America" joins "Don't Look Up" in its attempt to paint a picture of our ludicrous social landscape writ large. Both movies pronounce pop culture mania and social media fixation as the main symptoms of a devolving society. In "Don't Look Up," a pop star's relationship woes trend higher than the impending apocalypse. In "God Bless America," a teenager attempts suicide after learning he won't be a permanent fixture on a reality show. But while "God Bless America” takes aim at the symptoms of cultural devolution, "Don't Look Up" attempts to get at the root cause of it: corporate greed.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The Campaign

If you want all the zaniness of an Adam McKay movie but less of the pessimism of "Don't Look Up," "The Campaign" should be next on your list. While this McKay outfit doesn't whisk us away to the White House, it does place us smack-dab in the middle of a heated House election.

Marty (Zach Galifianakis) is a mousy challenger eyeing the seat Rep. Cam Brady (comedy genius Will Ferrell) has been warming for decades. This, of course, doesn't bode well for either candidate. While campaigning, Marty and Cam don't stop at attack ads and run-of-the-mill mudslinging, instead resorting to way below-the-belt political attacks. Sometimes, these attacks are more physical than figurative. And sometimes, the candidates don't direct them solely at each other. The movie's most outrageously funny moment arrives when an infant gets caught in the crosshairs of the campaign.

Of course, no McKay film is complete without searing criticism of the powers-that-be. In a similar vein to "Don't Look Up," "The Campaign" makes light of the influence of corporate money in elections. In this case, the corrupt Motch siblings have enough cunning and influence to rival the likes of Peter Isherwell. The brothers are master puppeteers, pulling the strings of one politician after the other, and Marty and Cam are no exception.

Downsizing

If the call to climate action is what caught your attention in "Don't Look Up," "Downsizing," directed by Alexander Payne, is similarly didactic about climate change — if not more so. While climate change is a heavy subtext in "Don't Look Up," "Downsizing" turns it into big, bold text.

In Payne's fictional world, human excesses are irreparably harming the climate, and downsizing, i.e., shrinking humans down to five inches, poses a nifty solution. Entrepreneurs even begin building suburban communities to house the downsized, collectively naming them Leisureland. Touted as a utopia, Leisureland is enticing to cash-strapped workers like Paul (Matt Damon), not for its minimal ecological footprint but for its economical lifestyle. To people like Paul, shrinking means dreaming big and living large.

A chance meeting with the Vietnamese political activist Ngoc Lan Tran opens Paul's eyes to the shortcomings of Leisureland. The community ends up being a microcosm of the real world, and all of its afflictions — poverty, ill health, crime — hit just as hard even when you're five inches tall.

The Other Guys

"Don't Look Up" may be the culmination of Adam McKay's long foray into political filmmaking, but "The Other Guys" marked the crucial point in his career where he went from directing lighter fare like "Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy" and "Step Brothers" to tackling systemic injustice.

Partners-in-solving-crime Allen and Terry are as unlike each other as two people can be, but their differences all but disappear when a crafty adversary emerges. So far, this sounds like your average buddy-cop movie, but in reality, it's far from it. This McKay movie turns the trope of the swashbuckling cop on its head, instead choosing to turn the spotlight on lowly forensic accountant Allen (Will Ferrell) and his blackballed partner Terry (Mark Wahlberg). Allen has never so much as fired his gun, while Terry has only ever had the misfortune of firing it at the wrong person (Derek Jeter).

While the rest of the NYPD is busy giving chase to petty criminals and blowing up millions of dollars' worth of property, our duo, by the sheer power of good detective work, stumbles onto a conspiracy perpetrated by a billionaire. The point McKay boldly makes in "The Other Guys" is one he continues to subtly highlight in each of his subsequent films, "Don't Look Up" included: Powerful institutions and the people that run them are constantly failing — whether due to incompetence or actual corruption. The people that rescue society are not suave but scrappy, not confident but determined, and not powerful but conscientious.

Wag the Dog

If "Don't Look Up" imagines what shape sensational media narratives take in a world full of corporate strategists and social media specialists, "Wag The Dog" imagines what they'd look like if a Hollywood filmmaker went to town with them.

"Wag the Dog" earned notoriety for eerily foreshadowing the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal and its turbulent aftermath. In this 1997 movie, when the U.S. President is proverbially (and almost literally) caught with his pants down, spin doctor Conrad Brean (Robert De Niro) and Hollywood producer Stanley Motss (Dustin Hoffman) are called to divert the ensuing media storm. Motss attempts to perform damage control using a novel method: inventing more damage elsewhere. He creates a fictional war against Albania and, by intricately sketching out the details, leaves little to the public imagination. A battle theme song and a tortured war hero become plot devices in Motss' master plan to get the President off scot-free.

The spin doctors and social media executives in both "Don't Look Up" and "Wag the Dog" are aided and abetted by a media infrastructure that's almost too easy to manipulate. The media ecosystem in both films bears resemblance to a toddler: It's easily distracted and far from serious. The titular phrase in "Wag the Dog" is, after all, a reference to diverting attention from the most important to the less important.

Sorry to Bother You

If you thought "Don't Look Up" delivered a scathing indictment of our class system, "Sorry to Bother You" achieves that and more: In one masterstroke, it takes aim at both economic and racial injustice, all while serving up laughs by the number.

Our protagonist Cassius Green (LaKeith Stanfield) is part of a class of bottom–feeders in a capitalist society that exploits them to no end. But when he joins the shady corporation RegalView as a telemarketer, he discovers his ticket out of poverty. You see, Cassius is a natural at using the most effective sales tactic there is: an eerily exaggerated form of "code-switching" that involves speaking over the phone with the distinct accent, confidence, and empowerment (verging on entitlement) of a white man.

Cassius then has to strike a complicated bargain with his conscience in order to ascend the corporate ladder. First, he is forced to shed his Black identity in order to succeed. Then, when he's given a promotion, he makes an implicit deal with the devil: his allegiance to RegalView in exchange for better wages and more prestige. This means he can no longer support his fellow workers in their own collective quest for better pay and working conditions.

Cassius understandably struggles to show class solidarity in a system that rewards the opposite. If you found yourself becoming heavily invested in Dr. Mindy's journey as he went from crusader to sellout and back to crusader, you'll enjoy Cash's equally volatile character arc.

Knives Out

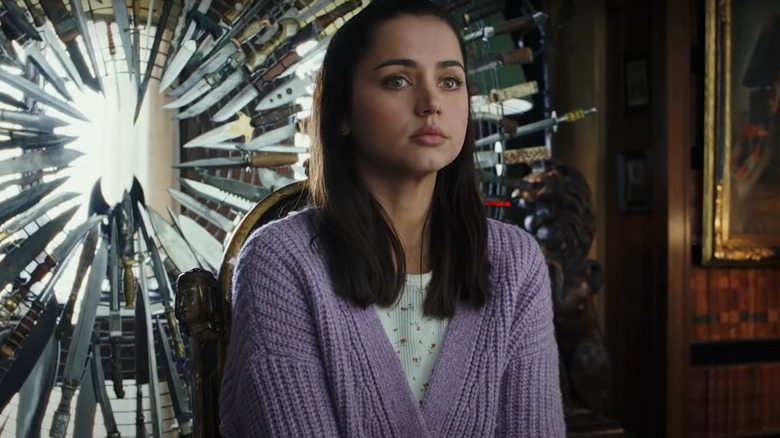

In the face of planetary destruction, even the influential elite in "Don't Look Up" are rendered powerless by their own flaws. The uber-rich Thrombey family in "Knives Out" experiences a similar kind of powerlessness when threatened with the end of the world as they know it, i.e. a snug and decadent one.

In Rian Johnson's mystery film, the suspicious death of the Thrombey family's patriarch leaves a power vacuum so great that each of its members is ready to fight, dupe, and kill each other for the chance to fill it themselves. Imagine their contempt, then, when they find out whom the late Mr. Thrombey has actually crowned the heir to his vast fortune: an immigrant, Latina nurse named Marta (Ana de Armas). But Marta's most discernible quality, and perhaps one the Thrombeys envy the most, is this: She literally cannot stomach lies. Meanwhile, the rest of the family eats deceit for breakfast.

Both "Don't Look Up" and "Knives Out" comprise a very similar smattering of characters. The smug, privileged band of antagonists in both films could easily be interchanged without significantly altering either film's ending. Like the politicians, media personalities, and technocrats in "Don't Look Up," the Thrombeys are largely oblivious to the real world and the outsized influence they have on it — an influence squandered through negligence and selfishness.

War Machine

If "Don't Look Up" satirizes bureaucracy in apocalyptic times, "War Machine" does the same with a catastrophe of a different kind: war. In "War Machine," celebrated General McMahon (Brad Pitt) is called to orchestrate America's exit strategy from Afghanistan. This would all work out fine, except for one thing: McMahon shows no desire to exit from Afghanistan at all. Instead, he intends to send in additional troops — but bureaucracy, bureaucracy, and more bureaucracy threaten to derail his plans. Meanwhile, an upcoming journalistic exposé also spells trouble for the general.

"War Machine" paints a visceral picture of the confusion, inefficiency, and ineptitude that can permeate a war. It also showcases how the complacency of stubborn authority figures like McMahon can exacerbate this mayhem. McMahon believes in winning wars, while nearly everyone else believes in ending them. Ultimately, this clash of ideals and the exacerbating bureaucracy is what prolongs the war at the cost of lives, time, and resources — much like political and corporate interests delay the proper response to the comet in "Don't Look Up."