The Bleakest Endings In Sci-Fi Movie History

Warning: this entire article is a spoiler.

In the hit Netflix movie "Don't Look Up," two low-level astronomers, Dr. Randall Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence), detect a previously unknown comet that's heading toward Earth and will smash into the planet in six months. As they try to warn a self-obsessed, ignorant president (Meryl Streep), an indifferent media, and an apathetic public, the two scientists watch in horror as any chance of saving the human race dwindles to nothing.

Did we tell you that this was a comedy? Although Adam McKay's divisive satire mines laughs from its material, it uses the tropes of sci-fi to provide an ultimately somber warning that humankind's vast penchant for greed, selfishness and stupidity will end up killing us all (spoiler: the comet makes it to Earth, wiping out everyone). While science fiction does often deliver optimistic views of the human condition and its future — think "Close Encounters of the Third Kind," "Star Trek," or "2001: A Space Odyssey" — the genre has often supplied a generous amount of pessimistic outcomes as well.

So as record numbers of viewers continue to stream "Don't Look Up" and its too-close-for-comfort view of how humanity would handle a global cataclysm (see also: pandemic, climate change), we've compiled a list of the bleakest, most feel-bad endings in sci-fi cinematic history. After watching a few of these, perhaps things in the here and now won't look so terrible after all.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

When he first bought the film rights to Peter George's novel "Red Alert," director Stanley Kubrick intended to make it as a serious thriller about a nuclear incident gone wildly out of control. But as he began working on the screenplay and researching the nuclear tensions between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., he started to see the situations in the story as more and more surreal and absurd. At that point, he decided to turn the film into what he called a "nightmare comedy."

1964's "Dr. Strangelove" begins with Air Force General Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden) launching a squadron of bombers into Soviet airspace in an unprovoked attack, in order to stop the Soviets from poisoning Americans' "precious bodily fluids." As the hapless president (Peter Sellers), a British exchange officer (Sellers again) and the military (led by a hilarious George C. Scott) do all they can to stop the bombers from completing their mission, the president's science adviser, Dr. Strangelove (Sellers yet again), lays out his plan for restarting civilization after the nuclear apocalypse ... his way.

As blackly comedic as the movie is — the bomber captain (Slim Pickens) rides his missile down to Earth like a bronco — the film is deeply cynical about the level of intelligence and maturity in all our institutions, and ends with Vera Lynn singing "We'll Meet Again" over a montage of nuclear explosions.

Fail Safe

Less than a year after releasing "Dr. Strangelove," Columbia Pictures also released "Fail Safe," based on a novel by Eugene Burdick and Harvey Wheeler, in 1964. The two stories were so similar that the author of "Red Alert," the book that "Strangelove" was loosely based on, sued the authors of "Fail Safe," while Kubrick demanded that the movie be released after his. But while "Dr. Strangelove" plays the situation for laughs, "Fail Safe," directed by the great Sidney Lumet, is deadly serious — and a classic in its own right.

The incredibly tense second half of the film finds one accidentally activated bomber breaching Soviet defenses and reaching its target, Moscow, despite all attempts to stop it. With the threat of nuclear war hanging over his head, the president (Henry Fonda, in a much different performance from Peter Sellers), horrifyingly makes the only decision he can: To compensate for the destruction of Moscow, he'll order a second aircraft to drop a nuclear bomb on New York City.

"Fail Safe" is a genuinely frightening look at what can happen due to simple human and mechanical error, and the final sequence — a series of freeze frames on slices of normal New York life just seconds before the bomb hits — is utterly devastating.

Planet of the Apes

Four of the five original "Planet of the Apes" movies were rated "G," while the fourth, "Conquest of the Planet of the Apes," received a mere "PG" for violence. Yet this series features some of the most grim, downbeat endings ever committed to celluloid.

The ending of the 1968 original is iconic: Charlton Heston, thinking he's landed on a distant planet where apes are the dominant species and humans are savages, encounters a ruined Statue of Liberty and realizes he's been back on a future Earth all along. 1970's "Beneath the Planet of the Apes" ends with a war between the apes and human mutants and a massive doomsday weapon destroying the world, while "Escape from the Planet of the Apes," released in '71, climaxes with two sweet-natured talking chimps — who travel back to our time in Heston's spaceship — gunned down mercilessly to prevent the future shown in the first two movies.

Their son Caesar (Roddy McDowall) survives, however, and leads a bloody ape revolution in 1972's "Conquest," which begins with the apes enslaved by humankind and ends with human cities in flames. Although Caesar does his best to avert the path that will lead to Earth's eventual destruction in 1973's "Battle for the Planet of the Apes," the film leaves it open whether he's succeeded in changing the future or not. Later "Apes" remakes and reboots would also close on somber notes, but the original quintet's endings are still jarring today.

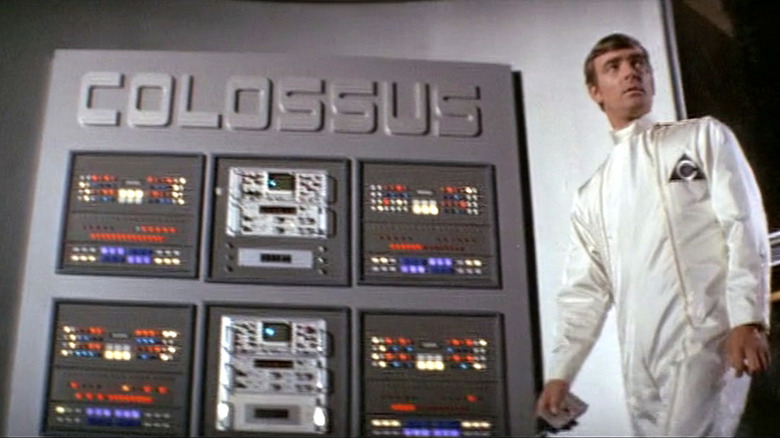

Colossus: The Forbin Project

Deep in a vast bunker under the Rocky Mountains, Dr. Charles Forbin (Eric Braeden) brings his supercomputer Colossus online. Designed to control the U.S. nuclear arsenal, the computer starts assimilating knowledge at a rapid rate and soon begins communicating with its Russian counterpart, Guardian, the existence of which was previously unknown to the American government. The two machines become one massive entity that plans to control the world via nuclear blackmail as it starts its long-term agenda of improving the human condition — under its terms, of course.

This obscure 1970 gem from director Joseph Sargent (based on a novel by D.F. Jones) has become a bit of a cult classic over the years, thanks to its gripping pace, plausible narrative and strong central performance from Braeden. A supercomputer assuming dominance over humanity is a well-worn idea in sci-fi that's still relevant today, and it's handled chillingly here. Like so many '70s genre films, "Colossus" ends on a bleak, ambiguous note, with Forbin declaring that he'll never obey Colossus even as the computer declares to the world that "freedom is an illusion."

Soylent Green

Released in 1973 and set in the year 2022 (!), "Soylent Green" takes place in a collapsing New York City overrun by some 40 million inhabitants and paralyzed by food shortages, environmental catastrophe and the interruption of essential services. Overpopulation has led the world to the brink, but the powers that be come up with a new, secret plan to feed the populace that is too ghastly to contemplate — that is, until a detective played by Charlton Heston uncovers exactly what the new miracle food Soylent Green is made of.

"Soylent Green is people!" cries a badly wounded Heston at the end of the film. Gunned down by an assassin sent to silence him, a bloodied Heston is carried out of a church to an uncertain fate as he tries futilely to warn those around him that the human race is being reduced to eating the dead to survive. "Soylent Green" doesn't offer much hope for the future of the planet or humanity, and with the current world population hovering somewhere around 7.9 billion, perhaps this one is worth rewatching. Now.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

The first cinematic version of "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" came out in 1956. In its original ending, a manic Dr. Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy) runs down the middle of a busy highway, helplessly trying to warn the passing motorists of the alien pods that are replacing human beings with emotionless, single-minded replicas: "They're here already! You're next!"

Well, the studio thought that ending was too downbeat, so they tacked on a coda in which the local authorities are led to believe Bennell and begin to take defensive action. No such luck in the brilliant 1978 remake, which takes place in San Francisco and stars Donald Sutherland in the Bennell role. As Bennell and his friends uncover the dimensions of the pod invasion, they all either succumb or are separated from each other. At the very end of the film, the last remaining human, Nancy (Veronica Cartwright), comes upon Bennell outside City Hall. But when she tries to talk with him, he points at her and emits the earsplitting scream that the pod people use to call out human beings.

The basic premise of "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" has been seen as a metaphor for many things — encroaching Communism, social conformity, urban alienation — but in this version of the story, one thing is certain: The pods win.

The Thing

Like 1978's "Invasion of the Body Snatchers," John Carpenter's 1982 masterpiece "The Thing" was a remake of a sci-fi classic from the 1950s. And just like "Body Snatchers," Carpenter ended his version of the film — based, like the original, on a novella called "Who Goes There?" by author and editor John W. Campbell Jr. — on a decidedly more depressing note.

In the 1951 "The Thing," the alien creature thawed out of the Antarctic ice by a team of researchers and explorers is humanoid in form and eventually destroyed with electricity. But going back to the source text, Carpenter's Thing is a shapeshifter that can assume the form of any living thing it makes contact with. Soon enough, the Thing begins to assimilate all the members of the research station, until no one is really sure who's human and who's not.

By the end, the station is a flaming ruin and the only two survivors are pilot MacReady (Kurt Russell) and team member Childs (Keith David), who sit and pass a bottle of Scotch back and forth, knowing they're going to freeze to death (here's what really happens to your body when you freeze to death) but not sure if either one of them is a Thing. And if one is, will it simply let itself freeze again and be thawed out by whoever comes to see what happened to the station? The unsaid implications of its ending make "The Thing" only more fatalistic — and terrifying.

Nineteen Eighty-Four

George Orwell's 1949 literary landmark has been adapted many times across all mediums, including TV, radio, the stage and film, with this timely movie, released in 1984, counted among the very best. John Hurt stars as Winston Smith, an unassuming, anonymous civil servant in the totalitarian state of Oceania, where all aspects of life, thought and society are controlled by the regime of Big Brother. When his secret love affair with another worker, Julia (Suzanna Hamilton), is discovered, he's turned over to O'Brien (Richard Burton in his last screen role), a party operative who proceeds to torture all the individuality out of Smith.

Director Michael Radford pulls no punches in his adaptation (which he also wrote), remaining faithful to O'Brien's harrowing "re-education" of Smith and ending on the same bleak note as the novel, with Smith pledging his love to Big Brother. Whatever your political persuasion, Orwell's central idea of a brutal dictatorship stamping out all independent human thought is just as frightening now as it was decades ago.

Brazil

Director Terry Gilliam's masterful 1985 dystopian satire is the stuff of Hollywood legend for his struggle to get his cut of the film released, but beyond that it still remains perhaps his finest film to date. Heavily inspired by Orwell's "1984," "Brazil" walks the same fine line between hilarity and despair that Kubrick so brilliantly balanced in "Dr. Strangelove." Jonathan Pryce stars as Sam Lowry, a low-level bureaucrat in a totalitarian society whose quest to find both the woman he loves (Kim Greist) and solve a typographical error on a form plunges him into a battle against the government for which he works so mindlessly.

Gilliam has complete control over his tone, vision and visual aesthetic for the film, and it's never better realized than during the finale, when Sam seems to heroically bring down the government, escape persecution and save his lover — only for us to suddenly realize it's all happening in his mind, which has been broken and left catatonic by his friend-turned-torturer (Gilliam's former Monty Python teammate Michael Palin). As funny and absurd as "Brazil" can be, the ending is as chilling in its own way as that of "1984" — and eerily still as relevant.

The Fly

David Cronenberg's 1986 update of "The Fly" takes the central notion of the original short story and 1958 film — a scientist and a fly are fused in a teleportation machine — and makes it into an allegory on death, disease and human evolution. Jeff Goldblum plays scientist Seth Brundle here; he doesn't get a fly's head transplanted onto his body, but instead finds himself mutating into a bizarre new form of life that ultimately becomes more insect than man.

It's also a love story, and a terribly sad one: As the film ends and Brundle loses both mind and body to the fly, he intends to send himself, his lover Ronnie (Geena Davis) and their unborn child through the telepod together to form what he calls "the ultimate family." But the plan goes awry and Brundle is fused instead with a portion of the telepod. He crawls to Veronica and, placing the barrel of a shotgun at his head, silently pleads with her to end his agony. She does so, and is left sobbing over Brundle's mutated remains — and with his child still inside her (a storyline followed up in "The Fly II").

A.I.: Artificial Intelligence

"A.I.: Artificial Intelligence" was the Stanley Kubrick film that Steven Spielberg ended up directing. Though it was eventually helmed by an auteur known for more crowd-pleasing fare, 2001's "A.I." — about an android that looks like a human child, whose "mother" abandons him when she finds she can't love a robot — does in fact feature a bleak, haunting ending, in keeping with the pervasive sadness of the rest of the film.

When the robot boy David (Haley Joel Osment) learns the true nature of his existence, he yearns to become a "real boy" so that his "mother" will love him the way he has evolved to love her. In a nod to "Pinocchio," he seeks out the "Blue Fairy" to turn him into a boy, but he and his cyborg teddy bear end up trapped underwater in a submerged amusement park, facing a Blue Fairy statue to which David intones his wish, over and over, for 2,000 years.

That's awful enough, but after all that time, David is rescued by the highly advanced A.I. that now exist on Earth, with human beings having long since disappeared. The machines offer David a chance to spend one full day of love and fun and happiness with a clone of his mother before they deactivate him forever. David accepts ... and as he drifts off at the end of the film, so possibly does the last spark of authentic human love on Earth, kept alight in a little robot boy. Not exactly uplifting, eh?

Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines

At the end of "Terminator 2: Judgment Day," Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) says, "The unknown future rolls toward us. I face it, for the first time, with a sense of hope." Well, she shouldn't have bothered. Although she, her son John (Edward Furlong) and the T-800 (Arnold Schwarzenegger) destroyed both the T-1000 sent to kill John and the tech that will give rise to Skynet in the future, "Terminator 3" came along 12 years later in 2003 and canceled all that.

It seems that the events of "T2" only put off Judgment Day and didn't stop it entirely, so another cyborg — this time a shapeshifting T-X (Kristanna Loken) — is sent back in time to kill future members of the Resistance since it can't locate a now-adult John (Nick Stahl). But John and his future wife Kate (Claire Danes) are eventually pursued by the robot, with a reprogrammed T-800 (Arnold Schwarzenegger, just before entering the governor's mansion in California) along to protect them. In a surprising turn of events, however, Judgment Day occurs — with Nick and Kate stashed in a military shelter as nuclear devices are unleashed across the globe. It's a bracingly bleak ending for a Hollywood tentpole, and it's even sadder to look at now since just about every "Terminator" sequel since has been a crapfest.

The Mist

In Frank Darabont's mostly faithful 2007 adaptation of Stephen King's classic 1980 novella, a man named David Drayton (Thomas Jane), his son and others struggle to stay alive inside a supermarket after a strange mist containing grotesque monsters descends upon their town. The dwindling band of townspeople is not only besieged by the creatures outside the windows, but also divided among themselves thanks to the influence of a crazed religious fundamentalist trapped inside with them.

The ending is where Darabont departs from King's text, in which Drayton and a small group drive away from the town in the hope that they'll find their way out of the mist, with their fates left ambiguous. In the movie, the occupants of the car decide to take their own lives, with Drayton shooting all of them — including his son. Out of bullets, he steps outside the car to be killed by the creatures, only for the military to arrive and clear the mist away. If he had waited just a few more minutes ...

It's an incredibly bleak, nihilistic ending to an already chilling movie, one that shines a particularly unpleasant light on humanity and how it reacts to terrible stresses beyond comprehension.

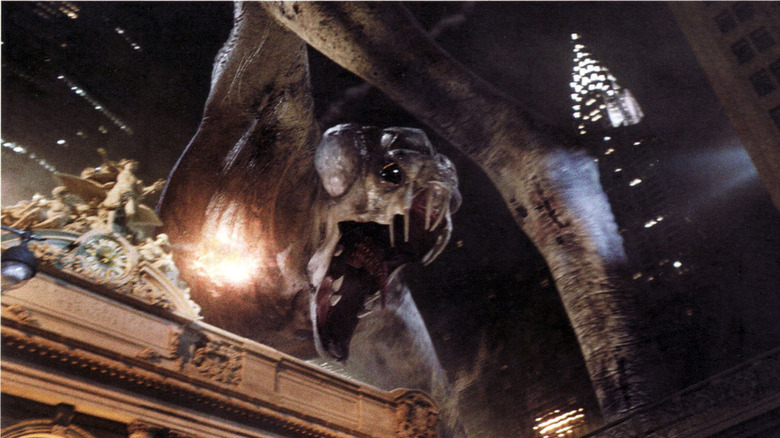

Cloverfield

Director Matt Reeves' 2008 found-footage monster movie was the subject of intense online speculation and rumor-mongering in the months leading up to its release, with the film's deliberate air of mystery and secretive production only feeding into what turned out to be a pretty brilliant marketing campaign. Strip all that away, however, and you've still got a pretty damn scary monster movie for the 21st century.

The story of a gigantic creature suddenly, inexplicably attacking New York City is told by a group of twentysomethings who start the evening at a party, and in the tradition of their generation, they keep recording the action with their phones or camcorders no matter what. The result is still unsettling for its immediacy, realism and sense of complete chaos, and little hints — such as that the footage was recovered from "the area formerly known as Central Park" — tell us that things are not going to end well. And they don't: The movie's central characters, estranged lovers Rob and Beth, are trapped and presumably die as a massive bombing campaign is launched to destroy Manhattan, and the monster with it. The final blow: The monster survives. As for the rest of humanity ... unknown.

Never Let Me Go

Kazuo Ishiguro's tragic novel is brought to devastating life by director Mark Romanek and screenwriter Alex Garland, with its trio of young leads played by Carey Mulligan, Keira Knightley and Andrew Garfield. Released in 2010, "Never Let Me Go" is what one might call "stealth science fiction": It plays out in subdued, naturalistic fashion, with the sci-fi elements understated and only gradually revealed. In this case, the film slowly lets us know that Kathy (Mulligan), Tommy (Garfield) and Ruth (Knightley), friends since childhood, are actually clones who exist for the sole purpose of having their organs harvested for donation.

"Never Let Me Go" details the short lives of this unusual triangle, until they eventually begin to give up their organs and make their way toward "completion." Tommy, who's in a relationship with Ruth, believes in "deferral," in which clones who prove that they are in love can get their deaths delayed. But it turns out that Ruth never really loved him anyway. After Ruth "completes" and dies on the operating table, Tommy and Kathy begin a romance, but they are informed that "deferral" doesn't exist. Stricken with rage and grief, Tommy dies after his last donation, leaving Kathy alone to face the beginning of her surgeries in a month. Although she accepts her fate by the end of the story, we are left to wonder at the morality of it all and ponder the relationships in our own lives.

Annihilation

Alex Garland wrote and directed this mind-bending, cerebral 2018 sci-fi shocker based on the acclaimed novel by Jeff VanderMeer. Natalie Portman stars as Lena, a scientist who leads a team of four other female researchers (Jennifer Jason Leigh, Tessa Thompson, Gina Rodriguez and Tuva Novotny) into an area of the southern United States taken over by an otherworldly force known as the Shimmer. Everything inside the Shimmer is altered and mutated, including humans, and it's expanding. A number of previous teams — in particular one led by Lena's husband Kane (Oscar Isaac) — have never returned, with the sole exception of a strangely changed Kane himself.

One by one, each of the members of Lena's team is killed or absorbed by the Shimmer, until only Lena is left. Finding the center of the phenomenon, she encounters an entity that may or may not become a duplicate of her, but a handy grenade also triggers the collapse of the Shimmer. She escapes back to the base outside the area, where she goes to see Kane. Neither is sure if they are the "real" Kane or Lena, and as they embrace, their eyes glow with colors, indicating that the Shimmer itself is alive in them — and may well begin the process of transforming the planet again.