Luke Cage: The Untold Truth Of The Marvel Hero

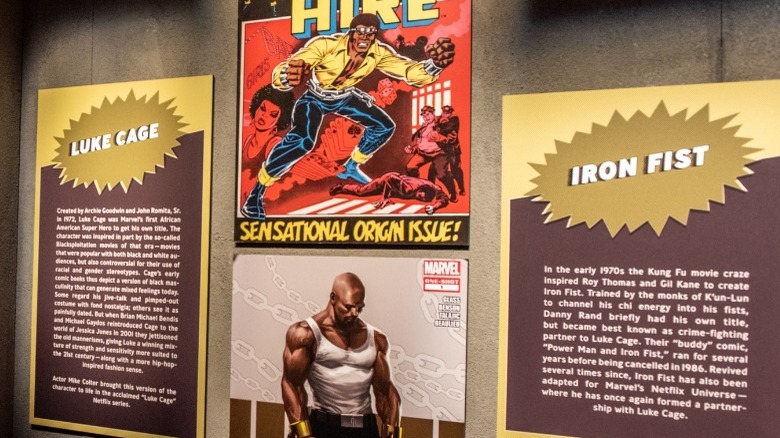

Created by comic book legends Archie Goodwin, George Tuska, Roy Thomas, and John Romita Sr., Luke Cage first appeared in 1972's "Luke Cage: Hero for Hire" #1. Initially, Cage's design was highly influenced by Blaxploitation films popular in the late '60s and early '70s. While this gimmick could have limited the character's popularity, Cage proved to be as resilient as his nearly indestructible skin and would evolve over the next five decades.

Cage was not the first Black superhero in Marvel Comics, but he was the first to appear in his own series. With comic books now filled with and headlined by Black characters — such as Miles Morales (Spider-Man), Falcon, Storm, Static Shock, Black Lightning, John Stewart (Green Lantern), Monica Rambeau, Black Panther, and more — it is difficult to imagine a time that Cage being the star of a book was an anomaly. By exploring key elements of Luke Cage's character and history, we can better understand how this risky idea evolved into an important figure in Marvel.

What is Blaxploitation and related entertainment

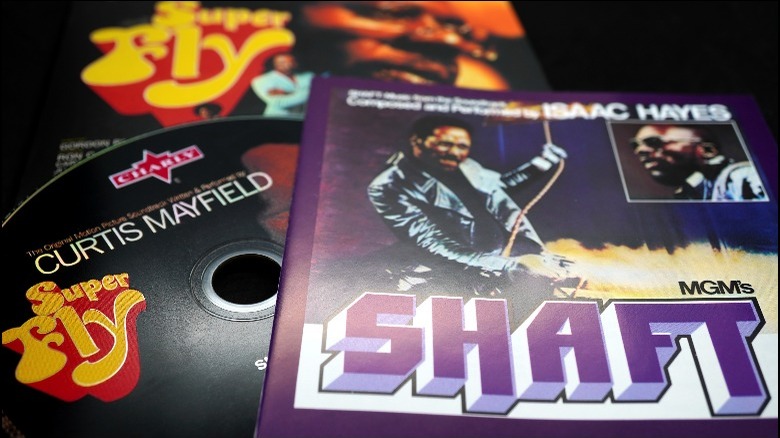

Blaxploitation is a film genre that was popular in the early 1970s. Reflecting on this type of film in the Los Angeles Times, Tre'vell Anderson describes Blaxploitation as an era in which "Hollywood trafficked in arguably unsavory depictions of Black life for a number of years." While the negative criticism of these films has softened as the legacy of this genre has become more complicated, it is clear that they impacted those at Marvel.

According to Bradford W. Wright in "Comic Book Nation," Marvel wanted a Black character with "street credibility." "While the Black Panther was a stately African prince and the Falcon was a middle-class social worker, Luke Cage was a lower-class Black man from the ghetto," Wright wrote. "Inspired by recent 'Blaxploitation' films like 'Shaft' (1971) and 'Super Fly' (1972), Cage's adventures took place in an inner-city underworld of pimps, drug-dealers, poverty, and white harassment."

The deployment of Blaxploitation tropes in Luke Cage showed that Marvel was not only interested in racial diversity but also concerned with economic diversity.

The state of Black characters in comic books

Though the horrors of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment are widely known now, the general public only first found out about these experiments on Black men in 1972, a few months after Luke Cage first appeared. Despite this, it was widely known that Black men were frequently targeted and more severely punished by a legal system populated with racist actors (via the American Sociological Association). So the idea of connecting Cage's origin to a prison experience wouldn't have seemed far-fetched at the time.

With that said, it is interesting to note that Cage was unique even when compared to other Black characters in Marvel Comics at the time. After all, the early 1970s had characters such as Misty Knight, Bill "Black Goliath" Foster, Ororo "Storm" Munroe, Sam "Falcon" Wilson, Luther "Deathlok" Manning, Eric "Blade" Brooks, and James Rhodes. And as Noel Murray wrote for "The Week" in an article titled "The Complicated History of the Black Superhero": "These characters had diverse backgrounds, purposes, and powers, and have endured largely because they were introduced as integral to the larger Marvel Universe — rather than being mere novelties."

This type of diversity is a reminder that Marvel didn't just want Black characters — the company wanted Black characters who represented the variety of experiences and backgrounds Black people came from.

Billy Graham – Cage's first Black creator

As mentioned above, the primary people to create Luke Cage were Archie Goodwin, George Tuska, Roy Thomas, and John Romita Sr., all of whom are white. However, the Luke Cage series did have a young Black creative. Though "white creators conceived and wrote the series," as Bradford W. Wright wrote in "Comic Book Nation," "a young African American artist named Billy Graham assisted with the illustration and occasionally the scripts."

Graham was also the only Black person working for Marvel at the time. Sadly, his name was not included in the credits for the "Luke Cage" Netflix series. As the New York Times wrote, "Billy Graham (his handle in the Marvel letter columns was 'the Irreverent One,' in acknowledgement of the more famous Billy Graham) was by all accounts a Renaissance man and a bon vivant with an infectious smile and hearty laugh."

Graham seemed to be a perfect fit for working on Cage in the early '70s. He was at home depicting Luke Cage, who was based in a Times Square movie theater. When discussing Graham during this time, Alex Simmons (who was a friend of Graham and the creator of the "Blackjack" comic book") said the following: "Billy was quite at home working on that material. His art references were on point because Harlem and the 42nd Street theater district were territories he knew very well. I roamed around with him in some of those places. To him, Luke Cage was a brother he could hang with" (via The New York Times).

Iron Fist and Cage's evolving title

Luke Cage's first title also represents another unique element of comic books: a series with an evolving title. From issue #1 till #16, Cage's title was "Hero for Hire." Issues #17 to #49 were named "Power Man" before becoming "Power Man and Iron Fist" in issue #50 until the title ended with issue #125. The initial name change reflected Cage wanting to adopt a proper superhero title. While battling a foe in issue #17, Cage explains a feat of strength by saying, "Just chalk it up to Black power, man." Liking the sound of "power man," Cage adopts the moniker as his superhero name.

Sadly, the title's sales declined while the "Iron Fist" series — running for fifteen issues from 1975 to 1977 — was also losing sales. Marvel decided to move Iron Fist into Cage's title, which allowed the series to continue for another 75 issues. In the story, the two heroes formally incorporate by creating the business Heroes for Hire, Inc. But this dynamic also enabled the series to explore race in a different manner.

With Iron Fist (aka Danny Rand) being white and wealthy, Cage found himself drifting away from his original low economic status. This happened to such a degree that when a person was specifically killing Black people in issue #123, no one reached out to Cage for help because it was believed that he no longer cared about the Black community. A citizen even screamed at Cage, "I remember when you was Black!" In other words, Rand's partnering with Cage helped evolve the latter character's relationship with race and class.

Christopher Priest's modernization of Luke Cage

Christopher Priest (born as James Christopher Owsley) has had a career in comics worthy of a book itself. Zooming in on how he impacted Luke Cage, this can best be described as Priest moving the character from a white gaze to a Black gaze. Prior to Priest becoming the writer of "Power Man and Iron Fist" in issue #111, Cage had mainly been written by white men who layered their understandings of Black identity onto the character. Once Priest started shaping Cage's stories, the character started to move away from stereotypes.

As Priest would write years later, "Issue #122 is also ground-breaking in that, here Cage admits his 'loud angry Negro' routine is a put-on something many whites do not realize. Many whites are shocked to see Queen Latifa or Usher or the late Tupac Shakur in film or on television shows speaking in complete sentences with a calm, even voice. It seems many whites don't realize the gregarious street voice is something we can turn on and off."

Enter Brian Michael Bendis

During the late '80s and '90s, Luke Cage had fallen in popularity. He was a character with lots of potential but no direction. Additionally, few people at Marvel were interested in developing a story with Cage in it — until Brian Michael Bendis was hired. After Bendis' "Ultimate Spider-Man" proved to be a critical and commercial success, Marvel gave the writer the freedom to tell whatever story he wanted. This story would be "Alias."

Centering on superpowered private investigator Jessica Jones, the character met and began a relationship with Cage. Reflecting on this new version of Cage, Abraham Riesman opined in Vulture: "By his own account, Bendis wanted to 'scrape off the dated 'funky honky' Blaxploitation part and focus on the man, a man of the 21st century,'" he wrote. "Part of that meant a chilled-out approach to his voice, including the removal of eye-roll–worthy slang and the stilted barks of a typical superhero."

"[Bendis] and Gaydos brainstormed a new visual approach, too," Riesman continued. "That meant no more bright, superheroic outfits and no more metallic accessorizing. The look they landed on was, appropriately enough, quite similar to that of Samuel L. Jackson in the previous year's 'Shaft' remake: pencil-thin facial hair (initially a mustache, later a goatee), modest streetwear with mostly muted tones, slyly charming speech patterns, and a crafty smile."

This version of Cage was reintroduced to the Marvel audience, and he was no longer a superhero. Instead, he ran a bar while also working as a bodyguard every now and then. Cage would not only forge a deep romantic relationship with Jones, but his renewed popularity allowed the character to be added to the "Avengers" comics.

Leading the Avengers and Thunderbolt

Luke Cage joined the Avengers when the series was relaunched in 2005 as "The New Avengers," and the first volume ran for 64 issues until 2010. By the time it ended, Cage was the team leader, and he would again get this position at the start of "New Avengers" Vol. 2. Cage would also become the leader of a new team of Thunderbolts for a period. These leadership positions represent two unique ways that Cage connects to larger cultural experiences.

One, Cage became the Avengers' leader around the time Barack Obama was becoming more popular. This elevation for Cage echoed the growing optimism for Black leadership in the United States during that time. Two, the Thunderbolts Cage led were all former criminals working towards redemption. Though Cage was sent to prison for fraudulent reasons, the character understood what it was like to be judged for his past and not his future. Talking about Cage's Thunderbolts to Comic Book Resources, Jeff Parker described picking Cage as the leader because he was the perfect choice to help reform villains and give them a "more noble purpose."

Continued political relevancy

From the very beginning, Luke Cage and his race were politically coded. As Alex Abad-Santos wrote for Vox, "Cage's brown skin — a feature that sets him apart — is the source of his power and strength. Cage acquires his powers — indestructible skin and strength — in prison. He volunteers his body for an experiment conducted by one Dr. Noah Burstein, something that calls back to the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment."

Additionally, when confronted with a different concept of the law, "Cage fundamentally understands that in practice, law isn't always fair," Abad-Santos wrote. "Cage knows there will always be good people, including good Black men like himself, who continually end up on the wrong side of the law. In writing these characters at odds, Goodwin [the first writer for Luke Cage] seems to be signaling or sketching around the ideas of implicit bias and structural racism, two topics that are still extremely relevant today."

As mentioned before, Cage — as a character at the intersection of race and lower-class politics — would continue to deal with larger political issues, from race and policing to the dynamics of an interracial relationship. These politics not only help Cage remain unique, but they also help media adaptations of him stand out.

Appearances in the Netflix shows

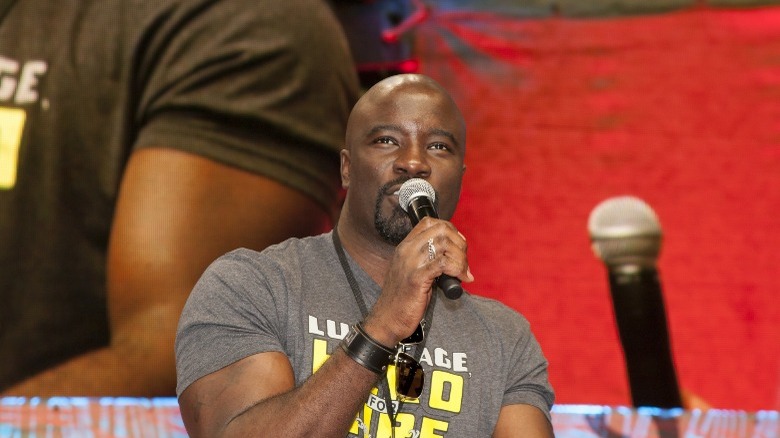

On October 14, 2013, Deadline reported that Marvel was developing a 60-episode package that included four series centering on mature versions of their characters. By November 2013, Disney announced that it had forged a deal with Netflix to create shows based on Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Iron Fist, and Luke Cage. Luke Cage quickly became a role that almost every Black man in Hollywood wanted, and Marvel/Netflix eventually settled on Mike Colter to play the character. Played by Colter, Cage appeared in "Jessica Jones" before starring in his own series.

Writing about the significance of Netflix's "Luke Cage" for the American Journal of Psychiatry, Dr. J. Corey Williams highlighted how the show managed to make a character created in 1972 feel more relevant than ever. "At first glance, you might think the new Netflix series 'Luke Cage' is just another platitudinous superhero drama from Marvel Comics. But, there is something quite different about this hero: the hero is a dark-skinned Black man dressed in a black hoodie. A celebration of this kind of image is radical change from the prototypical white male, caped crusaders casted in Marvel's most recent popular products (i.e., Ant-Man, the Avengers, Captain America, etc.)."

"The cultural and psychological significance of the show lies not just in having a Black superhero, but also in the specific superpower of being bulletproof that may strike an emotional chord in the Black consciousness," Williams continued. "As a show character proclaimed, 'There's something powerful about seeing a Black man bulletproof and unafraid.'"

Though this show only lasted for two seasons, it quickly became a touchstone for Black male representation in media.

The movie that wasn't made

Though Mike Colter was a fantastic Luke Cage, there were attempts to bring the character to the theaters at least a decade beforehand. For instance, due to the comic book bubble popping in the late 1990s, Marvel had to sell off the rights to many of its characters. One of them was Luke Cage, and the rights to develop this character into a movie were purchased by Columbia Pictures in 2003. As reported by The Hollywood Reporter, Ben Ramsey was initially hired to write the script, and the film — simply named "Cage" — would be "about a former gang member who is framed for a crime. In prison, he volunteers for a medical experiment that goes awry, giving him superstrength and bulletproof skin. Using his newfound powers, Cage escapes and becomes a hero for hire."

Though this film would never get off the ground, it was courted by superstar Black talent, including Jamie Foxx, Idris Elba, Tyrese Gibson, and Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson. Although a script related to this film has not been leaked, the evidence points to it being a standard superhero action film instead of an examination of Black America.

Ongoing popularity

Though Netflix's "Luke Cage" is over, the character's popularity transcends one show. Not only has Luke Cage been a fan favorite for five decades, but the character has also had a deep impact on popular culture. (On this note, "Luke Cage" was so popular it caused Netflix to have streaming problems.)

For instance, when Nicolas Coppola (the nephew of Francis Ford Coppola) wanted to build an acting career on his own merit, he knew he'd have to work under a different name. A comic book fan, Nicolas "chose the name Cage as a tribute to the comic-book superhero Luke Cage" (via Biography). Outside of entertainment, U.S. Social Security Administration data revealed a notable increase in children named Cage after the character's show streamed, Mashable reports.

However, the greatest sign that Luke Cage is an ongoing pop culture figure is that he was parodied by "The Simpsons." The longstanding "Simpsons" character Carl Carlson had a superhero alter ego named "Nuclear Power Man" and appeared in a comic book titled "Heroes for Rent or Lease to Own."

Character's importance to African Americans

With a history spanning five decades and a future that will last for decades more, it is clear that Luke Cage is an incredibly important character in Marvel Comics. Talking about Cage's creation, Matthew Teutsch, who holds a doctorate in English, wrote how Cage embodied two trends in the early 1970s that were in tension with one another.

"On the one hand, the apparent progress of the Civil Rights movement and the emergence of the Black Nationalist movements in the 1960s and early 1970s created social change, including changes within popular culture," Teutsch wrote. "On the other hand, Blaxploitation films arose out of this period, and since they put warm bodies in the seats and brought in money, Marvel saw an opportunity." As a result of these two elements, Cage is a character that functions as an evolving connection between Black politics and changing entertainment landscapes. In a piece for The Verge, Kwame Opam says this allows Cage and his stories to be a site that "examines Black culture through its music, literature, television, and film."

In 2010, Eugene Robinson discussed in his book "Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America" that Black America us no longer one entity, but "four distinct groups: the abandoned poor; immigrants and people of mixed race; the mainstream middle class; and the small but powerful elite." With more and more entertainment companies realizing the dynamic and various experiences that exist in Black America, Luke Cage remains a potent character that can be used to explore these various life experiences.