Things You Forgot Happened In The Star Wars Prequels

It's impossible for present-day "Star Wars" fans to imagine the anticipation that welcomed the prequels of the late '90s and early 2000s. Since "The Force Awakens" premiered in 2015, we've been relatively up to our necks in "Star Wars" content of some kind or another: three official "episodes" in the "Skywalker saga," two standalone movies, and "The Book of Boba Fett" is just the third of what will soon enough be dozens of seasons of "Star Wars" television on Disney+. There's too much content in modern life to keep up with, let alone be nostalgic for.

But in 1999, "The Phantom Menace" was released to a moviegoing public that hadn't seen a new star war at the movies for 16 entire years since "Return of the Jedi." It broke box office records despite tepid reviews and polarized fans. Well before everything even remotely profitable had a sequel, the prequels were the first big flashpoint during the internet's adolescence, and the first giant mainstream example of "they ruined my childhood!" outrage.

By the time the third and final prequel movie "Revenge of the Sith" came out in 2005, we had LiveJournal, MySpace, and the earliest days of Facebook to broadcast our opinions on the prequels to the world. And we all remember the craziest, most objectionable parts: Jar Jar Binks' entire existence, Anakin Skywalker's immaculate conception, the Force-ruining concept of "midi-chlorians," and so on. But there are several things you might have entirely forgotten about the prequels, in your rush to form an opinion about them and hold it in your memory. Especially as never-ending recent expansions to the "Star Wars" universe teach us to deal with variations in quality, the prequels are worth revisiting. When re-examined on the terms of their own admittedly shaky logic, they might even seem decently entertaining despite their flaws. These are some things you forgot happened in the "Star Wars" prequels.

The "mystery" of Darth Sidious is pointless

It's more or less universally agreed that the prequels were flat and sort of lifeless to watch. But one of the biggest reasons for that lifelessness has nothing to with any acting choices, or kid-friendly spectacles like the pod races. The strangest, biggest issue with the prequels from a story-telling perspective is George Lucas' decision to base all of the action around a mystery that viewers already knew the answer to: the identity of Darth Sidious, the "mysterious" villain manipulating events from the shadows.

Even though the Emperor isn't referred to as "Palpatine" in the '70s and '80s films, we recognize actor Ian McDiarmid as Senator Palpatine in "The Phantom Menace" without issue, and know instantly that he is also the hooded figure giving orders to Darth Maul and the Trade Federation. But it takes two more movies and six entire years for the characters in the prequels to figure this out. By keeping this in the background for the majority of the trilogy, Lucas sabotaged any chance of telling a comprehensible "good versus evil" story, as we had grown to expect of stories about Jedi Knights. Instead, we get bogged down in trade disputes, separatist factions, and clone armies that all turn out to be theater, and very little action where the heroes of the story even understand what's going on.

Qui-Gon steals Anakin's blood

What exactly are the Jedi Order's policies in regard to parental consent? It's strange, when you think about it, that Anakin is allowed to pledge himself for life to a monk-like order of spiritual warriors when still just a child himself. His mother is cool with it, but perhaps only as an alternative to a lifetime of slavery on Tatooine.

A small moment in "The Phantom Menace" shows how cavalier Jedis can be about manipulating children. Qui-Gon Jinn takes a blood sample from small child Anakin Skywalker without so much as a "please," and then lies when Anakin asks him what he's doing, saying he's merely checking "for infections." It turns out, of course, he was testing Anakin's midi-chlorian level. The existence of midi-chlorians, microscopic organisms that live in all cells and channel the Force, was dismaying to many "Star Wars" fans, as it gave a rational, scientific basis for the Force instead of a mystical one. But lost in the outrage was the question: Who steals a child's blood and then lies to his face about it?

Jedis don't care about slavery

It's impossible to watch "The Phantom Menace" and wonder why Qui-Gon feels the need to follow the rules on Tatooine at random moments. He attempts to use Jedi mind tricks on Watto, but when that doesn't work he feels obligated to bet the success of his mission, and Anakin's freedom, on a pod race, although he does use Force powers to influence a die roll. Ultimately, they leave Anakin's mother Shmi behind, a separation that will have dire consequences in the future, because Qui-Gon is once again in a rule-following mood.

But he's a Jedi! Why not just use your light-saber and other powers to bully Watto, who is all of two feet tall? Is the Galactic Republic, which is composed of thousands of worlds, really so fragile that it would be a huge scandal if one of their Jedi knight enforcers frees a single slave? In "A New Hope," the first Jedi we meet is Obi-Wan Kenobi, who cuts off a dude's arm just for laying hands on Luke. In "The Phantom Menace," Qui-Gon introduces us to a new kind of boring, "by the book" Jedi who flat-out tells Anakin "I didn't actually come here to free slaves." Too bad, little guy.

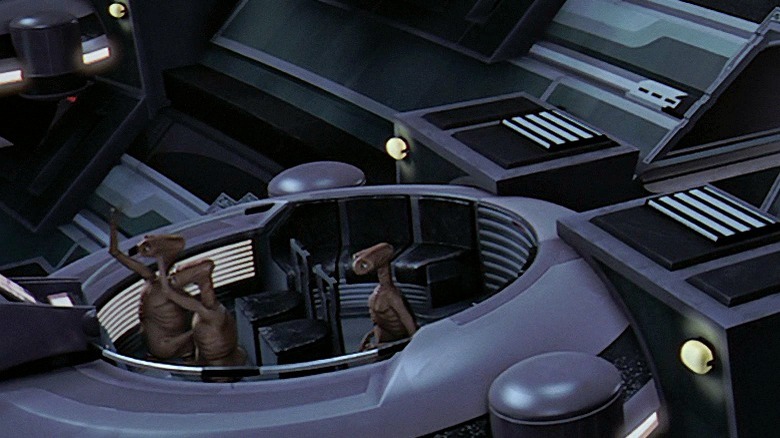

The E.T. aliens make a cameo

Every "Star Wars" movie begins with the same title screen: "A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away...." It's a fun way for George Lucas (and his successors) to play with the expectations audiences have for stories set in space. By implying these stories are set in our timeline, but long ago, the words give "Star Wars" the aura of legend and fantasy, mixed in with the sci-fi tropes that spaceships and lasers conjure up by default. In the prequels, there's an Easter egg that implies an even more direct connection to our galaxy, at least cinematically.

In "The Phantom Menace," George Lucas included a shout-out to his friend and collaborator Steven Spielberg, as the race of aliens from "E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial" is clearly seen as attendees in the Galactic Senate. It pays off Spielberg's own reference to "Star Wars" in his movie, when the titular alien sees a child in a Yoda costume and walks toward them murmuring "home." If both stories are on the same timeline, then E.T. really did just see an old friend, that his race has known for a "long time."

Palpatine's grand plan is incomprehensible

Despite our knowledge as viewers that Palpatine is actually the bad guy, his plan is so muddled and confusing that by the time he's engineered a war in "Attack of the Clones," it's entirely unclear which of his underlings are even in on the grand design, and how much he planned versus how much he's improvising. The awkward, wooden romance between Anakin and Padmé might be tough to watch, but at least it's clear what they're talking about, and why.

In the second prequel, Palpatine is pulling the strings on both sides: He's in control of the separatist factions that order multiple attempts on Padmé's life, but it's also his idea to have Anakin assigned to her as a guard. Did he want her dead or did he want them to fall in love, tempting Anakin away from the celibate Jedi lifestyle? By the time he's been kidnapped at the beginning of "Revenge of the Sith" by two of his own underlings, Count Dooku and General Grievous, we're no closer to understanding whether it's an elaborate ruse (to get Anakin to kill Dooku?), or if he's been hiding his real identity even from his own Sith apprentice. Nobody credits the prequels with masterful plotting, but if it's been a while since you've seen the movie, you might've forgotten just how nonsensical it really is.

Padmé is super chill about child murder

Both Season 2 of "The Mandalorian" and the new "Book of Boba Fett" take time to humanize and expand the culture of Tatooine's Tusken Raiders, perhaps directly because of how disposable and cartoonishly villainous they were in "Attack of the Clones." For reasons unknown, they raid a farm and kidnap Anakin's mother before he arrives on the planet. She dies in his arms just when he finds her. He murders an entire village of "sand people" in revenge.

But based on Padmé's reaction, it's not that big of a deal. Despite Anakin explicitly telling her he killed "every single one of them... women and children too," she only looks mildly concerned, as if killing innocent children of a sentient race is a regular part of the five steps. Padmé isn't just a young woman in love; she's a Galactic Senator who should have even more of a radar for human (or alien) rights abuses. Not only is this the strangest moment in one of cinema's most dead-on-arrival romances, it completely undercuts what is supposed to be Anakin's point-of-no-return moment in "Revenge of the Sith," when he ruthlessly slaughters the younglings at the Jedi temple. Padmé (and by extension George Lucas and the films) views this as horrific and unforgivable, but killing kids is already old hat at that point.

Obi-Wan Kenobi, private eye

In a trilogy full of dazzling CGI effects, explosions, and grandiose plot intrigue, the most overlooked and delightful aspect is Ewan McGregor's performance as Obi-Wan Kenobi. During the rare moments that the movies slow down and allow him a chance to channel the playful subtlety of Alec Guinness from the first movies, McGregor reminds us of the wry humor that's one of the reasons we loved "Star Wars" in the first place.

The middle section of "Attack of the Clones," when Obi-Wan goes on a solo mission to track an assassin and discovers the clone army, is a preview of how great the upcoming "Obi-Wan Kenobi" series on Disney+ might be. He cracks jokes, he bluffs his way into meeting with Jango Fett, and he speaks with lingering double meanings like in a classic film noir. It's almost a disappointment when the movie shifts back into laser beams and senseless warmongering. Most viewers have probably forgotten that anything intentionally funny happened in the prequels at all.

Count Dooku gives away the game

There are times when the prequel trilogies aren't just hard to understand, but also seem actively designed to be confusing. Late in "Attack of the Clones," for example, there's a scene between a captured Obi-Wan Kenobi and the villainous Count Dooku that seems like it should explain things. Normally when the bad guy taunts the trussed-up good guy, he explains his evil plan or at least gives it away because he thinks the good guy is about to be killed.

But Dooku tells Obi-Wan a maddening mixture of lies and truth. He claims, accurately, that "the Republic [is] now under control of the Dark Lord of the Sith," and that this is why he's leading a separatist faction against the Republic itself. But he's actually working on orders from Darth Sidious himself, so instead of a Bond-villain explanation of what we've seen so far, it's a strange smokescreen of fake truth that makes no sense whatsoever.

It's all allegedly to get Obi-Wan to join his cause: "Together, we will destroy the Sith forever!" But if he wanted to destroy the Sith, why would he ever have quit the Jedi? And it seems risky as all get out to risk blowing up Palpatine's spot as a secret Sith lord at that stage in the game just to throw Obi-Wan briefly off track.

General Grievous and his hacking cough

It's worth taking a moment to reconsider General Grievous, who perhaps even more than Jar Jar Binks represents the CGI-forward incoherence of the prequels. General Grievous is suddenly introduced in "Revenge of the Sith" as not just a major new villain, but one who has killed multiple Jedi in between movies during the Clone Wars. He's a four-armed, cybernetic droid army general that seems to exist solely to have a cool-looking toy that holds four lightsabers.

We bet you've forgotten one detail about the late Mr. Grievous: For unexplained reasons, he has a hacking cough that his multiple mechanical parts either cause or can't quite get rid of. Is the cough supposed to be intimidating? He seems like a strange collection of things people thought were cool about other villains: if you thought Darth Maul's double-bladed lightsaber was cool, this dude has four! You know how Darth Vader's breathing was scary? This dude has amplified coughing sounds, which are... even scarier, maybe?

Jar Jar Binks, annoying as he is, has a character arc from outcast to hero and was a new creation instead of a shameless fusion of existing "Star Wars" elements. General Grievous is creative bankruptcy at its worst.

The Jedi barely react to their own massive failure

"Revenge of the Sith" contains the moment that the entire plot of the prequel trilogy hinges on: the revelation that Palpatine is Darth Sidious. Finally, after the majority of three movies and more than 13 years in the plot of the story, the Jedi will realize that they've been deceived, right to their faces, and their worst enemy has been controlling the Senate and whispering in the ear of their potential "Chosen One" the entire time. To top it all off, they don't even figure it out themselves; Palpatine reveals himself to Anakin.

But this moment could not be more a shrug, unfolding with the attitude of an afterthought. The only recognizable Jedi present when Anakin shares the news is Mace Windu, who says only "then our worst fears are realized" and immediately moves on to planning to arrest Palpatine. Not a moment to take in the news, not a note of anger or disbelief in his voice whatsoever. Jedis are meant to be in control of their feelings, but even brainless droids have more emotional range in the prequels. It's as if at the end of "The Usual Suspects" (spoiler alert) the cop didn't drop his mug or even open his eyes wide, but just went "welp, that's on me."

"Revenge of the Sith" has a reputation as the better of the three prequels, and it does benefit from finally having everything out in the open, culminating in two fantastic duels between Anakin and Obi-Wan as well as Palpatine and Yoda. But after such a long journey to such a flat revelation, it contains by far the most frustrating moment of any of the movies as well.

Hiding Luke with his family is a terrible idea

At the end of the tragic events of "Revenge of the Sith," Padmé dies shortly after giving birth to Luke and Leia, and a plan is hatched to hide the children from the Sith. Leia is given to Senator Bail Organa from Alderaan, and given his last name as well to live an anonymous life as a member of his family. Makes perfect sense.

Why in the world is Luke, on the other hand, taken to Anakin Skywalker's home planet of Tatooine and given to his step-brother Owen Lars? Even if Obi-Wan believes that Anakin is dead, since he did leave him down to one limb and burning alive, why "hide" Luke by giving him to a known relative of Anakin's and also giving him the last name Skywalker? Why not at least call him Luke Lars? It's the clearest example of George Lucas writing himself into a corner and hastening to get everyone in the right place at the end of the prequels.

Does Obi-Wan lose his memory between films?

If you watch "Star Wars" in order from Episodes I to IV, Obi-Wan Kenobi is a huge jerk in "A New Hope." Obviously, he plays it pretty vague in regards to referring to Anakin Skywalker and Darth Vader as different people when Luke has questions about his own parentage, and chooses not to mention Luke's twin sister. But he's also incredibly rude to R2-D2 and C-3PO, droids that he's known and fought alongside for decades.

"Revenge of the Sith" makes it a point to mention that C-3PO gets his memory wiped, explaining why he doesn't recognize Obi-Wan, but the prequels make it impossible not to wonder why Obi-Wan wouldn't at least mention that he recognizes the droids from his adventures with Anakin Skywalker, and what a stunning coincidence it is to see them together after 16 years with Anakin's own son. He literally says, "I don't seem to ever remember owning a droid" when R2 claims to belong to him, even though he and R2 fought in battles together. Including R2 and 3PO at every turn in the prequels was just a lazy way to give them the appeal of the original movies, and Obi-Wan's overall story is the unfortunate victim of it.